By P. Nicole King

Journal of Southern History

Volume 83, Number 1,

February 2017

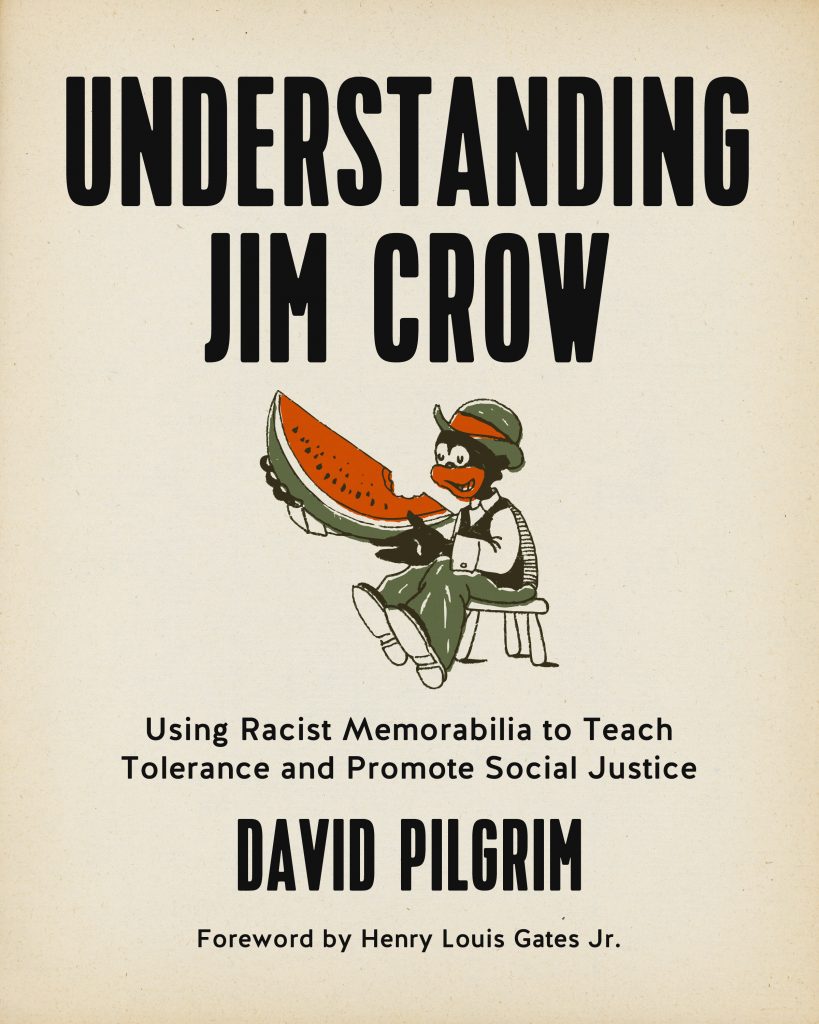

David Pilgrim is the author of Understanding Jim Crow: Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice and the founder and curator of the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan. The museum is “the nation’s largest publicly accessible collection of racist artifacts,” which are “used as tools to facilitate a deeper understanding of historical and contemporary patterns and expressions of racism” (p. 172). The book is organized, clear, and engaging, with many high-quality color images from the museum’s collection, making it an important and affordable book for teaching the history of racism and aspects of social justice to undergraduate students in many fields.

Pilgrim writes, “I am a garbage collector—racist garbage” (p. 1). The museum’s primary goals are to document and provide a safe space for the discussion of the social and historical implications of structural racism in the United States through directly engaging racist material culture. Pilgrim’s collections primarily focus on everyday objects—salt and pepper shakers, postcards, matchbooks, and popular culture items—where racism has been made material in quotidian ways.

Both the museum and the book point toward a truth and reconciliation process, as Henry Lewis Gates Jr. states in the foreword, to confront how racism is embedded in the history of this country. The first two chapters of the book are fascinating and original explorations of why Pilgrim came to collect racist objects and how these objects can function as unorthodox teaching tools.

In the second chapter, Pilgrim shares the basic pedagogical premise of the book. First, “you have to reach people where they are,” and second, “intellectually beating down someone makes teaching them improbable” (p. 34). Understanding Jim Crowis an example of the importance of public history projects that bring difficult social issues out from the shadows.

Chapter 4 explores the caricatured black family—mammies, Uncle Toms, and pickaninnies.

Chapter 5 offers a more detailed investigation of “Flawed Women,” and chapter 6 addresses “Dangerous Men” in breaking down different racial stereotypes and addressing issues of gender, class, and region. [End Page 199]While these later chapters provide a necessary context for the book, and especially its many images from the museum collection, they break no new scholarly ground.

The final chapter, “A Night in Howell,” is a fascinating conclusion that returns to the narrative approach of exposition used in the earlier chapters. The reader is taken to a Ku Klux Klan memorabilia auction in Howell, Michigan—an area known as a historic hotbed of the Klan and white supremacy—where Pilgrim bid on a Klan robe. The Livingston County Diversity Council invited Pilgrim to bid on the Klan robe so it could be used to promote social justice.

The skillful dramatization of the racism Pilgrim experiences in Howell and the attempts by some in the community to overcome the past of white supremacy is a fitting conclusion to a book that speaks to both the hard-fought progress toward justice and how very far we, as a country, still have to go to challenge white supremacy in its many forms.

Pilgrim’s book is an important read for publicly engaged scholars. He writes, “I learned that a scholar could be an activist, indeed must be” (pp. 4–5). It is vital for scholars in the humanities and social sciences to engage with Pilgrim’s perspective in the same way it is important for visitors to the Jim Crow Museum to engage in an act of envisioning justice. Understanding Jim Crowfunctions as a traveling exhibition, expanding the reach and audience of the museum.

Some of the images in Pilgrim’s book are disturbing. However, that is the point.