By Nichelle Smith

USA Today

February 7th, 2019

Everyday there seems to be a new revelation that somewhere in the past, a politician has appeared in blackface.

As if Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s medical college yearbook picture isn’t bad enough – if he is determined to be in the 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School photo, he’s either the man in the Ku Klux Klan robes or the man in blackface – he admitted in a press conference last weekend to darkening his face with shoe polish to be Michael Jackson in the ‘80s. Now, we’ve learned that Virginia’s state attorney general, Mark Herring, blacked up his face in 1980 to portray rapper Kurtis Blow at a college party. Before Northam, there was Florida Secretary of State Mike Ertel who resigned after a Halloween party photo of him posing as a female Hurricane Katrina victim in earrings, headscarf and blackface turned up.

Not to mention the seemingly yearly apologies from either a celebrity who wore blackface for Halloween or a fraternity whose members wore blackface for fun at a party. Just last year, Megyn Kelly was ousted from her “Today” show hosting job after an on-air discussion in which she defended using blackface for costumes.

This image shows Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam’s page in his 1984 Eastern Virginia Medical School yearbook. The page shows a picture, at right, of a person in blackface and another wearing a Ku Klux Klan hood next to different pictures of the governor. It’s unclear who the people in the picture are, but the rest of the page is filled with pictures of Northam and lists his undergraduate alma mater and other information about him. (Photo: Eastern Virginia Medical School via AP)

A relic of minstrelsy, a form of popular entertainment that was rooted in the mimicry and mocking of plantation slaves, blackface fell out of vogue last century as the country examined itself during the civil rights era and as African Americans gained more political power. Given the vast public disapproval after each incident surfaces, it would seem that most people understand that blackface is wrong.

So what, then, accounts for all of the modern instances of white people in blackface? What is it about blackface?

Both curiosity about blacks and contempt for them lie at the bottom of it, says David Pilgrim, director of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University in Michigan. It gives some people an opportunity to act out anti-black prejudices. It gives others a way to act out curiosity. “You get an opportunity to walk like, talk like, look like what you imagine black people to be,” Pilgrim says.

Imitation, in these instances, isn’t a form of flattery. “People don’t seem to learn the lesson” presented each time a blackface incident surfaces, says Dwandalyn Reece, curator of music and performing arts at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “They’re not really trying to understand how the stereotypes work” to demean and degrade black people.

“When you reduce someone to a stereotype, it is a way of distancing yourself from them,” Reece says. Blackface is a means to assert superiority, to elevate “whiteness” and set it apart from “blackness,” she says.

Some people would argue that they are just having fun imitating black people, especially the celebrities they love. So what’s the big deal? It’s the separation of blackface from this country’s painful history of slavery and Jim Crow oppression that adds the insult to the injury.

“Just putting black on your face, that represents such a foul time in our history. When it’s done out of sheer humor, it’s just not funny,” said Shirley Basfield Dunlap, associate professor of fine and performing arts at Morgan State University in Baltimore and coordinator of Theatre Arts.

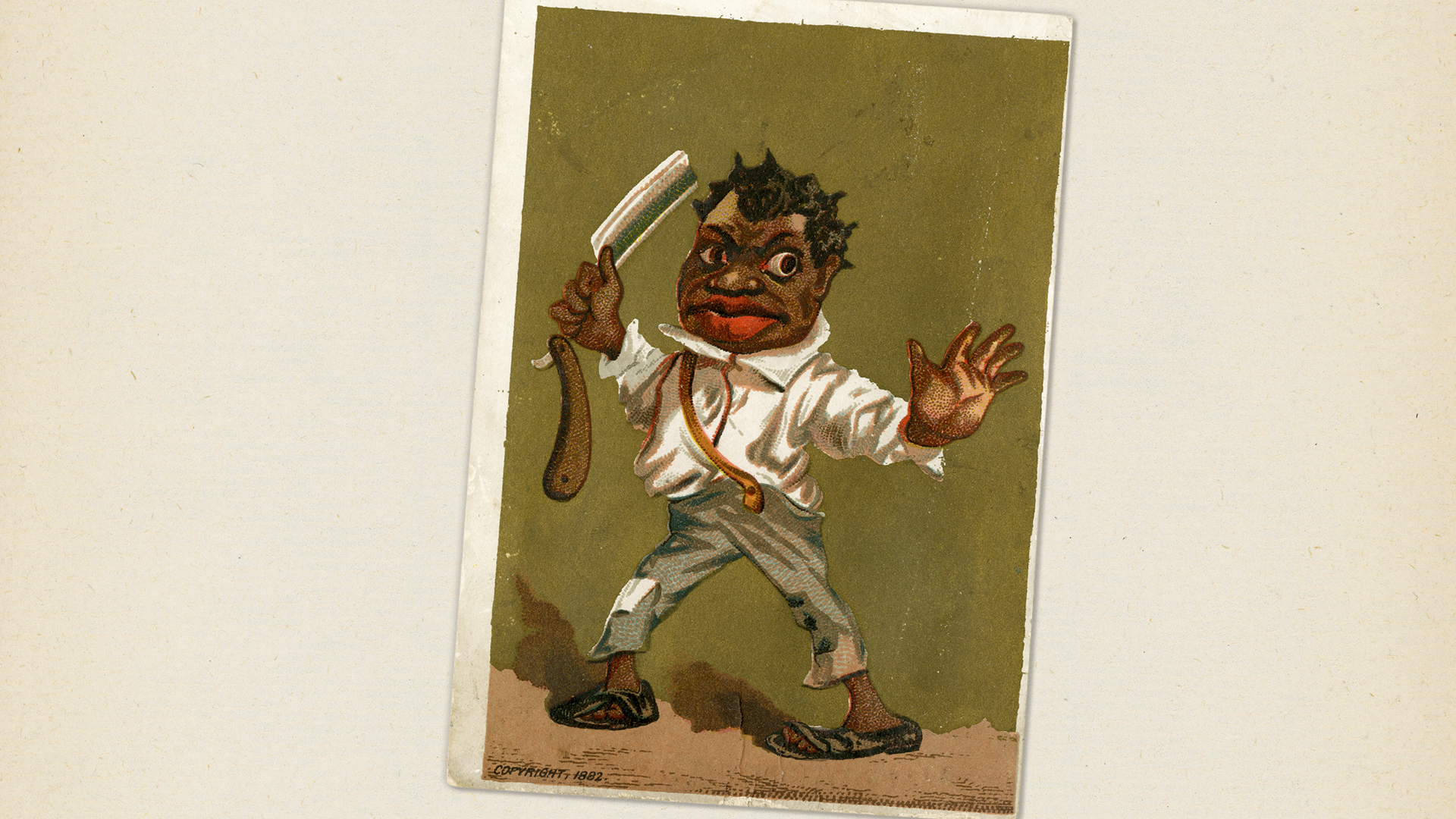

Minstrel shows featuring white performers in blackface got their start in the 1830s. With the popularization of radio and motion pictures in the 1920s, professional minstrel shows lost much of their national following. However, amateur minstrel shows continued in local theaters, community centers, high schools, and churches as late as the 1960s. (Photo: Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University)

American minstrelsy, in shows featuring white entertainers in blackface, dates to at least the 1830s. “It was an opportunity for whites to mimic blacks and what they saw on plantations, where they would see blacks entertain themselves or talk among themselves,” Basfield Dunlap says. Slaves would do Juba dances steeped in their West and Central African heritage and talk in dialect that cobbled together English and African words.

The first popular performer of minstrel shows, Thomas Dartmouth Rice, created the Jim Crow character in the 1830s, featuring blackface, huge painted lips and bulging eyes, after getting a slave to teach him about a singing black folk character. Basfield Dunlap notes the irony for the slave: “(Blacks) had to teach white performers how to be caricatures of them.”

Minstrel shows featuring blackface became one of the most phenomenal, popular forms of entertainment in America, especially after the Civil War. The shows were as popular on Broadway and in traveling shows throughout the South as “Hamilton” or “Wicked” might be today and, as evidenced by D.W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film, “The Birth of a Nation,” the blackface images conveyed by the shows were powerful in reinforcing racist caricatures of blacks. Menacing rapists, lazy watermelon eaters, coddling mammies and comic simpletons, all with blackened faces, moved from the stage to the screen as entertainment evolved. There was Al Jolson with his “Mammy” songs in 1927 in the first film with sound, “The Jazz Singer.” Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll’s “Amos ‘n’ Andy” radio show lasted from 1928 to 1960; the 1951 television version starring black actors was widely denounced as racist and the NAACP was successful in getting it pulled off the air.

Minstrel shows featuring white performers in blackface got their start in the 1830s. With the popularization of radio and motion pictures in the 1920s, professional minstrel shows lost much of their national following. However, amateur minstrel shows continued in local theaters, community centers, high schools and churches as late as the 1960s. (Photo: Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, Michigan)

Mid-century stars like Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Mickey Rooney and Shirley Temple performed in blackface in their movies, though those scenes are largely cut from showings today. Amateur performances persisted until well into the ’60s and high schools mounted blackface minstrel show productions the same way they might now do Broadway musicals.

The stereotypes reflected the views of most whites at the time and were fully integrated into American culture. Beyond entertainment, caricatures of mammies and pickaninnies — dark-skinned children with densely coiled hair — as well as grinning, bug-eyed black men adorned everything from postcards to cookie jars.

This is how people really saw blacks then, Reece says, and blackface was one of the primary ways to express that.

Pilgrim says that for the most part, those who wear blackface now, including young white men in fraternities and at prestigious institutions, know exactly what it implies. “It’s a part of the privilege of being white in our culture,” he says. “They are doing it in a safe, white space consistent with the mores of their in-group.”

In other words, they do it because they want to and they can. And ultimately, “it’s a choice to do blackface,” Reece says. “One that is rooted in oppression and a lack of values for the (dignity of) other human beings.”