By Matt Sutherland

Foreword Reviews

June 21st, 2019

The birth rate in this country is plummeting for a very obvious reason: Women don’t want babies. But the reason women don’t want babies is something conservative Republicans hate to admit: Having children is expensive and burdensome, and the US government provides mothers with very, very little help. There’s no paid leave, many women lack healthcare, there’s no financial assistance for nurseries or childcare facilities. All the while, the work of maintaining a household and raising kids is just plain hard, especially when you consider that most mothers are working full time.

Faced with these obstacles, even women who desperately want children are saying no, or are only having one child. They’re discouraged, and it doesn’t help when they learn that the governments of approximately fifty countries around the world require that mothers receive six or more months of paid leave. The enlightened leaders in these countries realize that a healthy economy needs plenty of workers. That, and stable governments need a solid tax base, which is only possible with an adequate number of citizens paying taxes.

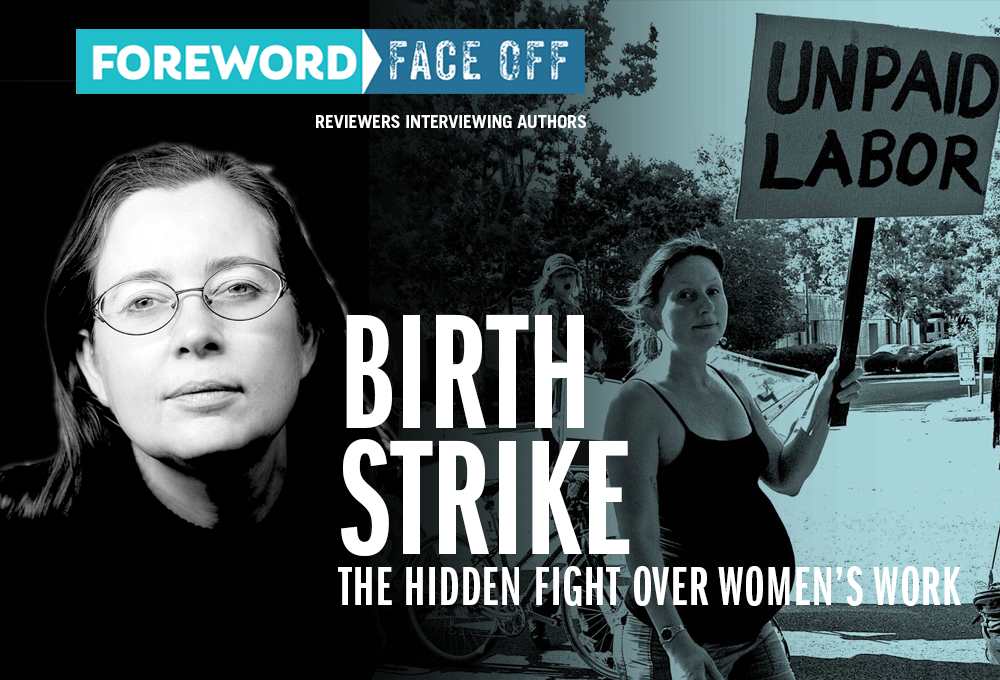

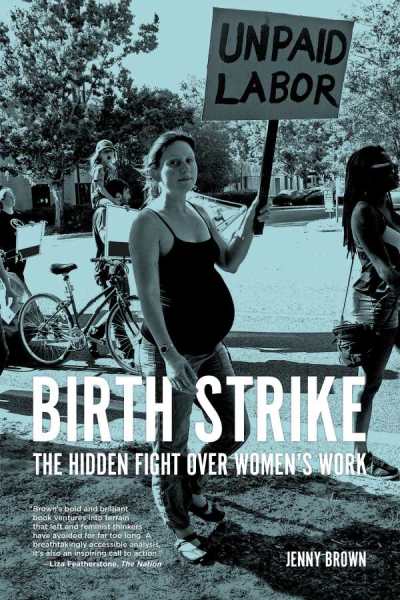

This week’s interview is with Jenny Brown, the author of Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work, one of the most thought provoking titles we’ve seen in years. In a nutshell, Jenny believes women have finally had enough: They’re refusing to have more babies until this country’s leadership recognizes the work they do is vitally important and worthy of government support.

Matt Sutherland gave Birth Strike a starred review in the July/August issue of Foreword Reviews, and he basically demanded the opportunity to do this Face Off interview with Jenny. We were all too happy to oblige.

Matt, take it from here.

Alright, let’s get this question out of the way. Is it remotely possible that we might see a coordinated effort amongst women to shut down their wombs until lawmakers enact some serious legislation to help mothers bear the load of pregnancy, birth, and childcare? It’s such a fascinating, compelling idea—could it really happen?

We’re not calling for a birth strike in this book, we’re just reporting that it is happening—we think women are on a spontaneous, uncoordinated birth strike due to bad conditions. But if we had called a birth strike, say ten years ago, we would think that we’d been fabulously successful. The birth rate was expected to rise after the great recession, but instead it’s fallen further, to a record low. So these are not temporary effects, but basic problems of our economy. We have to ask, what is an economy for if it doesn’t provide enough support for us to reproduce ourselves?

The abortion debate (war) is at a fever pitch again with new, extreme laws passed in Georgia and Missouri, and a conservative majority on the Supreme Court seemingly itching to take on Roe v. Wade. Can you help us connect the dots, please? How does birth control and abortion figure into the discussion of women’s work, as it concerns corporate CEOs, religious leaders, and Republican lawmakers?

What we’ve seen is that establishment think tanks are particularly concerned about the lower birth rate. They worry about economic growth, Social Security and Medicare, and military funding and personnel. Some even go so far as to say that if you’re going to have small government, you have to have bigger families to make up for the cuts they want to implement—cuts in Social Security, health care, unemployment insurance, welfare, education funding, and so on. They really expect the “family” to absorb the shocks. And by “family” they mean largely women, and women’s unpaid labor.

For example, when patients are discharged from hospitals “quicker and sicker” or when young adults can’t find jobs, or when parents retire, they expect the family to be there as a safety net. But long hours and inadequate pay mean that people are having smaller families and some are having no children at all. So that has created a policy imperative to increase the birth rate, which has translated into establishment support for laws that restrict abortion and birth control access. In Texas, where restrictions and regulations closed eighty-two family planning clinics after 2011, birth control use went down and childbearing rose 27 percent for women in affected areas, compared to areas that still had birth control access.

We’ve been here before. In 1873, when all birth control and abortion was outlawed under the Comstock Law, one of the worries at the time was that the birth rate had been dropping, especially among native-born Protestants.

In a sense, you’re advocating for a new, comprehensive definition of women’s work, one that factors in childbearing, childrearing, and even housework as uncompensated labor that benefits the greater good of society. This is also a radical idea—and ingenious. Is there some legal positioning behind the shift in thinking (terminology)? Might a class action lawsuit or somesuch be in the works? Are there other legal initiatives working their way through the system that might affect the uncompensated labor argument?

The 1960s women’s liberation movement made demands in this area which have gotten lost over the years. One branch demanded “Wages for Housework,” while others demanded a guaranteed annual income so that women wouldn’t be made dependent on a male breadwinner and his employer. Certainly, the current legal basis for abortion rights, based on privacy, is not the only legal approach to our right to control our reproduction. The anti-slavery 13th Amendment, which bans involuntary servitude, could also be applied. Feminists in the early 20th century tried to use this argument, as well as the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, to defend birth control, but it never stuck in court. However, legal arguments generally follow the agenda that is created by people’s movements.

The USA is uniquely the USA—maddening as that is, at times—but why do you think this country has so thoroughly failed to care for her mothers, when nearly all other wealthy countries provide generous government-funded programs? A striking example is Finland’s attitude toward her mothers-to-be. As you write in the book, “a few weeks before the baby’s due date, the government sends each family a box stuffed with well-designed baby clothes, a snowsuit, and other essential gear, all free. The mattress-lined box can even be used as a crib.” Now there’s an inspiring example for us. Why are we such Scrooges?

Other countries have gone through the coercive phase that we’re going through now. France now has world-class universal health care, universal childcare, and two years of paid parental leave by law, but it didn’t start out that way. The French tried everything to confront low birth rates in the 19th century, including bans on birth control information and crackdowns on abortion. The church even constructed hundreds of “foundling wheels” where babies could be anonymously abandoned. When the women’s liberation movement established the right to birth control and abortion in the 1970s, France already had in place a universal health care system, so birth control and abortion were simply included, giving women full reproductive control for the first time. Then in the 1990s, as the birth rate flagged, France strengthened the supports for parents that we see today.

One reason we haven’t won these things yet in the US is that our labor movement doesn’t really have a political party to call its own. So when we make even a modest demand for, say, six months paid family leave, the employers who control both parties in Congress block it—they don’t want to provide the funds or the flexibility. But fifty countries have laws that provide for six months or more paid leave, so we know it’s possible to win that here. We think it’s powerful to break through the widely-believed myth that the US is the best.

The 2018 fertility rate in the US is down to a 32-year-low of 1.7 children per woman—an unnerving fact to conservatives and feminists alike, but not so easy to attribute. In the book, you cite Steffen Kroehnert, a German researcher who debunks the idea that when women join the work force, they have fewer babies—a popular theory amongst conservatives. In western European countries, Kroehnert writes, “the fertility rate is higher in countries with a higher labor market participation of women. … The question today is not if women will work. The question is if they will have children.” Can you talk about the reasons women are having fewer babies? Do you think women will respond to enticements?

In my group, National Women’s Liberation, the idea we were on a birth strike made perfect sense. I remember a consciousness-raising meeting in 2015 where many of us testified that we had one child and were stopping, not because we didn’t want more, but because the conditions were too difficult. We described the “double day” of a full day at work and then another eight hours of care work. We talked about having to go back to work a few weeks after giving birth, and the expense of childcare. We cited the physical toll that pregnancy took on our bodies, especially when combined with long work hours and lack of sleep. Among the childless, some of us didn’t want any kids, but others did but couldn’t figure out how to make it work with unreliable health care and long work hours. Sixteen of these testimonies are in the book.

In the US, we’ve gone backward in a way. In the period after World War II, the family wage was expected to support a male breadwinner, his spouse, and their children. The family wage was an excuse for paying women less, and made women dependent on men for survival, but it did have a progressive element, which was that at least employers were indirectly supporting the family care job. As wages stagnated in the 1970s, both spouses went out to work to make up for it, and now the family care job is squeezed into the day after paid work. Rather than go back to a sexist family wage system, we propose that we go forward to a social wage—the term in Europe for benefits that everyone in the society receives, such as health care and childcare and paid vacations. They also have shorter work weeks.

Your book is filled with unexpected eyeopeners. In your chapter on cheap labor you talk about the tactics corporations (and local governments surreptitiously) use to keep labor costs down. And then you write, “Part of the motivation for ‘ending welfare as we know it’ during the Bill Clinton administration was that unemployment was low and wages were rising as a result. Pushing mothers of small children onto the job market was a quick way to bring down wages, because it increased the pool of workers who needed jobs.” Whoa. And I thought the motivation was simple cruelty, though I’m a bit slow. Will you please walk us through the role women and childbearing play in this country’s macroeconomics, unemployment, wages, and so on?

Economists understand that a tight labor market, with low unemployment, leads to wage gains, and we’ve even seen a slight uptick in wages due to our currently low unemployment rate. This is why during big war mobilizations, which cause a shortage of workers, governments usually institute wage controls, otherwise workers would have leverage to increase their pay. But I’m not arguing that drops in the overall population are the cause of wage fluctuations—for one thing, wages and employment go up and down due to the roughly ten-year business cycle. Having babies can’t be the cause of those changes, it’s too slow. But capitalism does require growth to function, and it has always relied on growth in population, which includes new families buying the things they need to live. In Japan, which has a lower birth rate than ours, a stagnation of the economy has been blamed on an aging and declining population. Still, a declining population isn’t a worry for the 99 percent. There’s plenty of goods and services to support the retired and those who aren’t working, our productivity has doubled in the last fifty years. But a declining population does squeeze profits and that’s what these think tanks are worried about.

To head in a different though related direction, please help us understand why access to contraception remains such a controversial subject when polling confirms that the vast majority of this country wants it to be readily available? Your work to make the morning-after pill available over the counter is much admired, by the way.

Thanks! That was a ten year battle, including everything from civil disobedience arrests to a lawsuit. We finally won in 2013 when a judge ordered the Food and Drug Administration to put morning-after pill contraception over-the-counter for all ages. We expected the Bush administration to fight us, but we were surprised that the Obama administration was also actively opposed. This showed us that opposition to birth control had become a mainstream political position, despite public opinion. Even among those who oppose abortion, 80 percent support birth control. So that made us think that this intense politics around both birth control and abortion wasn’t just politicians pandering to a conservative religious base, it must come from a desire for higher birth rates, which is something we’ve seen before in our history. Once we started looking, we found lots of evidence for that.

Will you do us all a favor by offering a personal riff on abortion politics, please, factoring in all the latest, mostly depressing, happenings. You’re an expert on the topic. It would be enlightening for you to offer us your perspective.

The backlash against reproductive freedom is nothing new. Shortly after Roe v. Wade legalized most abortion, the 1975 Hyde Amendment excluded women whose health care coverage was Medicaid. Since then, we’ve fought many other serious restrictions. And now several states have passed laws to ban abortion outright, hoping to end up before the Supreme Court. It’s clear that a majority of the Court wants to overturn Roe. The question is, can they maintain their legitimacy if they allow states to brand as criminal anyone who gets or gives an abortion? Thirty percent of women get abortions—that’s a lot of people to criminalize.

At the same time, technology has advanced since the days of back-alley abortions. Medication or pill abortions are now used in thirty percent of clinic abortions in the US. But the pills are also readily available without prescription through internet grey sites, as well as overseas. There’s never been a better time to have a safe, at-home abortion! Prohibitions of recreational drugs don’t work, and this prohibition won’t either. But they will try. And it’s clear that the reason they’re trying is to force women to take on the work of bearing and raising children without providing adequate support or compensation. Abortion bans are the cheap way, compared to providing childcare, paid leave, and healthcare.

What’s the one thing about the book or topic that you find interesting and noteworthy, but doesn’t get the attention it deserves?

Immigration has always been the primary US method for increasing population. But I think the government’s crackdown on immigrant communities has left the impression that the establishment opposes immigration, when in fact most employers and even most Republican lawmakers support immigration. However, they don’t want immigrants to have rights, which is why you see all this high-profile enforcement and terror. At the same time president Trump is trying to stop refugees from violence in Central America, he’s supporting a 30,000-person increase in the H2B guest worker program. Guest workers are ideal for employers, because they don’t have any rights on the job. They can be deported if they don’t work fast enough or object to dangerous working conditions or wage theft. And in the long term, they won’t be able to organize against injustice or vote, because as soon as their employer doesn’t need them, they can be kicked out of the country. Even largely pro-immigration Republicans such as Jeb Bush want to get rid of family reunification because, he says, parents and children of workers often need services such as health care and education. These thinkers are gleeful that working-age immigrants have been “raised on someone else’s nickel,”—US employers are getting workers without contributing to their upbringing. This is a huge ripoff of mothers, families, and communities in sending countries, but it is consistent with the desire of employers in the US to obtain workers without paying anything towards our social infrastructure.