Originally published on Bitch Magazine

By Victoria Law

July 10th, 2015

Today, the Confederate flag finally comes down from outside the South Carolina capitol building. Two weeks ago, activist Bree Newsome scaled the flagpole and took it down herself, but now it’s coming down for good after legislators and the governor agreed to remove the stinging symbol of American racism.

While we can take time to rejoice in the (permanent) removal of this symbol of white supremacy, let’s not assume this flag is the final vestige of slavery in the United States. “Many states celebrate the era of slavery with Confederate holidays and by honoring the defenders and architects of slavery while ignoring the history of enslavement,” explains a new video by Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). The video, called “Slavery to Mass Incarceration,” connects the history of slavery (and its accompanying justification of white supremacy) with today’s epidemic of mass incarceration. The Equal Justice Initiative works with people sentenced to death row, juvenile prisoners, people who have been wrongfully convicted, people whose poverty denied them effective legal representation at trial, and those whose trials were marked by racial bias and/or prosecutorial misconduct. The organization is based in Alabama, where 647 of every 100,000 people is in prison—and 56.5 percent are African-American.

EJI founder and director Bryan Stevenson narrates this history, from the first Africans shipped to the colonies in 1619 (holding the legal status of servant, he points out), to today’s racial profiling, police violence, and mass incarceration of African Americans. But “Slavery to Mass Incarceration” is no dry narrative—time lapse sequences by artist Molly Crabapple illustrate each fact with a haunting (and beautiful) watercolor image.

As the Confederate flag comes down, it’s important to recognize that white supremacy is not simply a relic of the Bad Old Days. As both “Slavery to Mass Incarceration” and Bree Newsome point out, it is still very much alive—and active—throughout our nation. The legacy hasn’t gone away simply because a flag has been removed. We have seen this in the police killings of Black people across the nation—from 12-year-old Tamir Rice to 93-year-old Pearlie Golden. We also see it in the disproportionate arrests and imprisonment of African-Americans. In 2013, among people in state and federal prisons, nearly one-third of the 1,412,745 men were Black. In local jails, Black people made up 35 percent.

These disproportionate numbers, the video reminds us, are some of the enduring legacies of slavery and white supremacy. “Today, a presumption of guilt is assigned to many people of color who are disproportionately arrested, convicted of crimes and sent to prison. African-Americans are six times more likely to be sent to prison for the same crime as a white person.”

The facts are all around us: This spring, the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice released a report finding that in San Francisco, African-American women were arrested at a rate 13.4 times higher than women of other races. This disparity isn’t new, the report notes, but has been growing since 1980 when Black women were 4.1 times more likely to be arrested than women of other races. San Francisco isn’t alone in disproportionately policing, arresting and incarcerating Black women: In 2013, more than one-quarter of the women in state and federal prisons were Black.

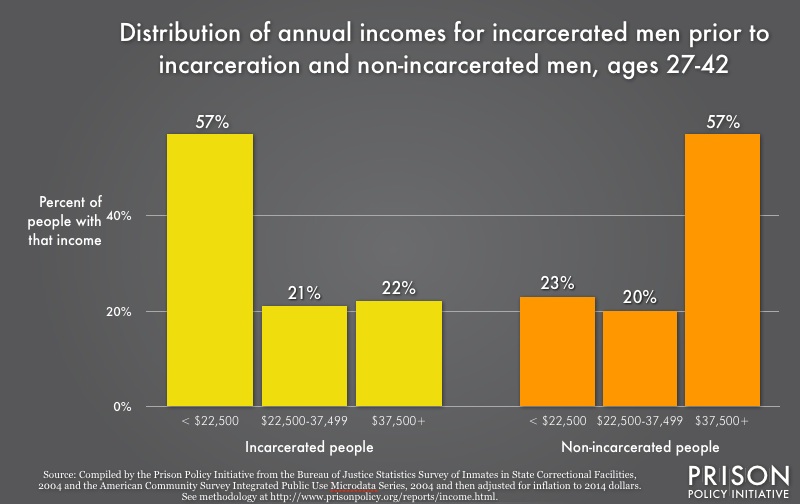

Just this week, the Prison Policy Initiative, a criminal justice think tank, released Prisons of Poverty, a report providing the pre-incarceration incomes of people in prison. The report proves what many who have been working around issues of mass incarceration have known for years: People who end up in prison are poorer than their non-incarcerated counterparts even before they go to prison. It also shows another legacy of racism and white supremacy: the vastly lower incomes of African Americans even in the twenty-first century.

Before we dive into the report’s income disparities by race, let’s look at the overall findings. The Prisons of Poverty report demonstrates that, despite all the talk of Leaning In, this country still has a long way to go before closing the gendered wage gap. The median income for a woman who is not in prison is $23,745. In comparison, the median income for a man who has not seen the inside of a prison cell is $41,250.

Now let’s add in the incarceration factor. The median annual income of an incarcerated woman before she went to prison was $13,890, a 42 percent difference from her non-incarcerated counterpart. For men, the disparity widens dramatically—$19,650 is the pre-incarceration income, a 52 percent difference from his non-incarcerated counterpart. When you add race into the equation, incomes drop dramatically. For Black men in prison, the pre-incarceration income is $17,625, the lowest of all the races surveyed. For Black women, their $12,735 is only slightly above the $11,820 earned by Hispanic women before prison.

“Racial bias remains a serious problem and is a direct and lasting legacy of American slavery and our failure to deal with the history of racial injustice,” the “Slavery to Mass Incarceration” video sums up. That’s a belief shared by many working to end racism in all of its forms, including mass incarceration.

So today, even though one symbol of white supremacy has been taken down, we need to keep focusing on what needs to be done to fully eradicate this poisonous legacy.

Related Reading: In America, There Are 5.4 Million Adult Citizens Who Are Not Allowed to Vote

Buy Resistance Behind Bars:

Buy Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind: