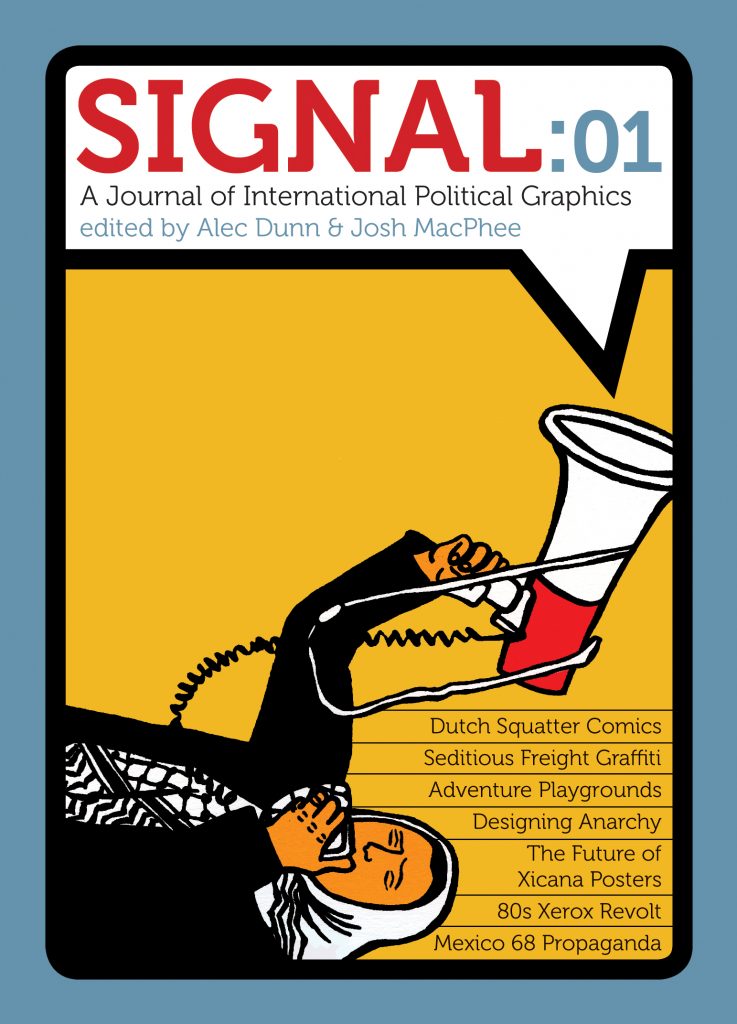

An interview with Josh MacPhee and Alec Icky Dunn of Signal, a new journal of international political graphics and culture.

What are your backgrounds in political artwork?

Josh MacPhee: I grew up in the punk rock scene, and began making zines and t-shirts in high school in the late ’80s and early ’90s. Through the do-it-yourself ethos of the punk scene, and also by becoming politicised with the U.S. invasion of Iraq in the early nineties, I turned towards making more political art. I became involved in the anarchist movement, particularly the creation of “infoshops,” which consisted of bookstores, libraries, meeting spaces, Food Not Bombs, and lo-fi community organizing. I made posters and graphics for the anarchist community, as well as broader left activism around diverse issues such as prisoner’s rights, healthcare, anti-war, and global justice. In recent years, I’ve become increasingly interested in the history of what I was doing and have worked on a number of projects unearthing and analysing politicised art production.

Alec Icky Dunn: I have a similar background but also, when I was a teenager, I worked putting up posters for rock clubs, so I started making my own (political) posters to put up on my rounds of the city. It has been a sporadic but continuous pursuit since then. Art and politics started to get a little more focused when I lived in New Orleans in the late ’90s. I was involved in some of the solidarity work around the “Angola 3” political prisoners in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, and I also saw the first few “Celebrate People’s History” posters, which Josh was curating and printing. I made one and sent it to him unsolicited, which he then printed, which was pretty exciting at the time! A few years later we ended up living together in Chicago and have collaborated on many projects since then.

I think one of the main things we have in common is we both come to political art not only as producers but also as fans. We are both very interested in the history of cultural work as it relates to political struggles and we’re both excited about its potential (both historically and currently) to add to social movements and movement-building.

Why did you feel there was a need for an international journal of political graphics and culture?

Josh: Over here in the States, when you see any political graphics or artwork used at all, a lot of it is the same set of images, which have been used over and over again. But there is an incredibly rich amount of artwork and aesthetics that have been used in left/anti-authoritarian/liberation struggles all over the world, and I think we are in some ways hoping to expand the base of what people here think is possible.

It’s easy for a lot of political graphics to blend into our sensory landscape. For example, you see a poorly copied poster with a fist or a peace sign or an anarchy symbol and it’s an easy thing to ignore, because it’s boring! And often those uncreative, ineffective, posters are tied to uncreative and ineffective protests. Obviously, it’s not quite as simple as that, but I think we’re looking for ways that cultural work can help clarify political movements and work with them to feel more urgent or effective.

The U.S. Left has a fairly distinct tradition of graphics, but when we started discovering stuff from around the world, we saw many commonalities and a lot of cross-pollination. In 1968 you had the agitprop artists in Paris and the poster brigades of Mexico City both making really expressive, simple images to be put up on the street. We can see the influence of this work subsequently in the student movements in the late 1960s and early 1970s around the globe, later within the anarcho-punk scene in Europe, then also taken a step further with the silk-screening movement that worked in South African townships during the anti-apartheid struggle, and more recently during the financial meltdown and bottom up re-organisation in Argentina in the last decade.

This influence was not only aesthetic – strong, minimal, and often biting images – but also organizational. Artists were setting up ad hoc workshops so that people could make posters for things in a really immediate way. These are interesting models and examples of what can be done.

Alec: We are also interested by things that haven’t had that type of cross-pollination, because there are really different graphic traditions all over the world. For example, I just saw a Japanese poster for a protest against the U.S. military base in Okinawa – it was really vibrant and celebratory looking. It had very bright colours and a cartoony goose honking in one corner. This type of poster is almost unimaginable in the U.S. and I’m not sure why. A friend of mine just came back from Tanzania and she brought some fabrics, once again very bright colours, and what you would think of as African style, but with political themes. The point is that we think there’s a lot to be gained from a more international perspective.

And finally, we think there is value is history and memory. For instance, we’ve been slowly accumulating images – posters, book and magazine covers, stamps, et cetera – from the CNT/FAI in Spain. They often have really amazing illustrations or type treatment. What’s interesting to me is that it’s a good example of what a broad-based working class movement looks like. These images were made by people in the movement, people who had a craft; they were working illustrators, typographers, and printers.

Josh: As largely self-taught artists from the United States, it has been a life-long struggle to try to find and understand people making artwork akin to ours in other parts of the world and in other time periods. The U.S. tends to be so myopic.

Signal is an opportunity to both reveal a rich and diverse historical (and contemporary) field of cultural action that is outside of our view and to share it with others. I feel strongly that this culture is something that should be held in common by all those struggling for equality and justice in the world, but is too often locked in the vaults of cultural institutions or the heads of individuals.

What is the range of culture you intend to cover?

Josh: We’re very ecumenical. As a visual artist, and in particular, a maker of political graphics, that is what I’m most knowledgeable about, but I’m interested in a much wider range of cultural production. Social movements have successfully used everything from printmaking to song, theatre to mural painting, graffiti to sculpture. We’re open and curious about this entire range of expression and its implications for both art and politics. For future issues we are already collecting material related to comics, newspaper promotion, guerrilla print studios, photocopy art, pirate radio, architecture, billboard correction and postage stamps.

Most of the articles are illustrated interviews with artists and designers, rather than essays. Why did you take this approach?

Josh: There is very little politically engaged art writing today that doesn’t exist in rarefied academic or art-world discourses. Unfortunately, most critical exchange excludes the vast majority of those who might be interested in the intersections of art and politics.

Alec: We wanted to show as much of the work as possible! That’s really one of the big focuses of what we’re doing. And also it was partly about expediency. This was a first issue, and it was hard to solicit longer writing when people didn’t really know what we were about. We are hoping to have more writing – not just interviews, but ideas, criticism, and even (gasp!) theory.

Josh: Our goal is to incorporate critical writing, but it is a challenge to find essays that are accessible, well-written, and insightful. So as we develop that writing, we have been excited to publish interviews with engaged cultural workers whose voices are rarely, if ever, heard.

The first issue seems quite strongly grounded in broadly anarchist politics. Is that a fair assessment of your intentions for the journal?

Josh: This is the background we come from, but we are not interested in narrowly focusing on cultural expressions that come from groups or moments that self-define as “anarchist.” I’m much more interested in exploring the breadth of left cultural expression, and trying to understand how social movements and cultural producers within them articulate their politics and goals, both to themselves and others. The field of politicised visual communication has largely been ceded to advertisers, but it is essential that engaged artists attempt to understand how their work operates in the world, and looking at a wide range of examples seems like a good place to start that process.

Alec: I think it’s not quite a fair assessment. One of the five features was strictly anarchist (Rufus Segar), two had strong associations (about Red Rat and adventure playgrounds), and the other two didn’t identify as anarchist at all. I think you could say we’re pro-anarchist, but I don’t think it defines this project by any means.

Back to Alec “Icky” Dunn’s Artist Page | Back to Josh MacPhee’s Author Page