By Patrick A. Coleman

Fatherly

March 11th, 2019

Family planning expert Jenny Brown argues that the declining American birth rate is a push back against unrealistic economic expectations thrust on mom and dad.

The US birth rate is at its lowest point in three decades and sliding. The population shrinks daily even as the private sector struggles with a labor shortage and politicians promised GDP growth incompatible with a contracting workforce. Though they rarely get credit for it, parents grow the economy by raising the kids who wind up participating in it. When adults opt out of parenthood en masse — there’s a fine example of this in Japan — economies sputter and stall. So it behooves both policymakers and private sector leaders to consider why Americans in prime child-bearing years are opting out of procreation. And it turns out there are some concrete and fairly obvious answers.

The economic strain of parenthood has increased. The social strain of parenthood has increased. The professional strain of managing multiple incomes has increased.

Jenny Brown has watched both these trends and family planning trends. As a National Women’s Liberation organizer, Brown led the campaign to make the “morning-after pill” available over-the-counter and discovered that couples were putting off having children not out of disinterest but out of fear. They understood the difficulty of providing for and educating a child in a hyper-competitive culture. They understood they would receive minimal government support. They were making informed decisions to either not have kids or to have fewer kids. The un-childing of America was underway.

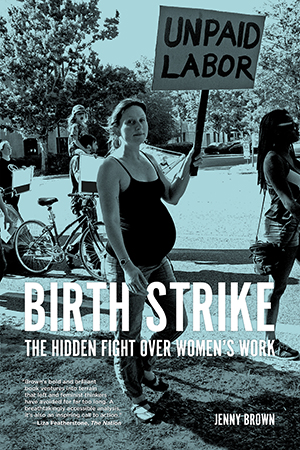

In her new book Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work, Brown documents this phenomenon and posits that until the government starts supporting families with social programs that help make child rearing easier, adults will eschew parenthood and parents will skip the second or third kid. Fatherly spoke with Brown about this emerging dynamic and what fathers can do to navigate what is, in a literal and figurative sense, a confounding labor market.

I want to make sure that this gets represented accurately. You’re arguing, essentially, that because the American government doesn’t provide meaningful support for parents, we’re seeing a decline in birth rates, which you’re calling a birth strike. How did you come to that conclusion?

We were involved in a campaign to get the morning-after pill over the counter and we talked about how difficult it is to have kids. Many of the members of our group had had one and we’re stopping because they didn’t have access to paid leave, or the amount of time off that they had was laughable — maybe a week or two weeks. They had health insurance issues, trouble paying just for the birth. Even when they had insurance there were a lot of other costs involved. Then there was paying for after school and summer programs and just the exhaustion of working eight hours a day, at least, and then coming home and trying to have a family life. They just decided they couldn’t handle having a second.

What about the women who didn’t have kids?

Many of us didn’t have kids but wanted them. We were facing financial instability and inflexibility by employers and the cost of childcare. In other countries, there are subsidies or wraparound services or very long paid leaves. But we were mostly taking unpaid leave. And then we started to see the headlines about the birth rate going down and that’s when we made the connection.

So, when it’s harder to raise kids, people have fewer kids. Makes sense. And you’re certainly right that America subsidizes parents a great deal less than most developed nations. Why do you think we’re so reluctant to help American parents when it’s clear they need more help?

Well, I’m not sure it’s reluctant. At least on the part of just ordinary people. But I do think it’s reluctance on the part of the employers.

After World War II, the sexist ideal was to have a family wage. That meant that one breadwinner would support the family. They would support the children and a spouse who made it their full-time job to do the care work in the family. And so that was 40 hours a week to support a family. Now it takes 80 hours or more a week to support a family. But employers have not added anything for that family care job.

Employers now get 80 hours, at least, of labor so there’s less eagerness on the part of couples to do additional domestic work. That resonates with me, but I wonder if there’s a solution.

For the unionized section of the workforce, there used to be an idea that the employer’s paycheck had responsibility over what is possible in a family. In our group, we say rather than the family wage we need a social wage. That’s the European term or all of these programs that cover everyone, including long paid leave, long vacations, health care, child care, and elder care. We have to reckon with what happened in America. We had a system. That system is gone but it wasn’t replaced with another system.

That system has traditionally been understood as “bad for moms.” But it strikes me as pretty damn bad for dads as well. What is the advocacy role for fathers here?

Men worry about the economic situation. They worry about healthcare, child care, and housing. The same pressure is applied. So the birth strike is definitely not just something that women are deciding. It’s something that couples are deciding. We’re in a different situation than the 50s because dads are really doing tremendously more. They see all of the same things that women see when they’re doing care.

With that visibility that fathers have, and those higher stakes, will that help?

I think creates the possibility for more political cohesion when parents go to make these demands.

If the difficulty of parenting is leading to a decline in birth rates, that will ultimately affect the GDP and shrink eligible employees. It looks like the private sector is working against it’s best interests. What’s the deal? Do they just not get it?

Well, for the last 20-years they have been getting away with it. Until recently families have been taking these burdens on themselves. They have been paying out for the child care and struggling and enlisting grandparents to fill in the gaps. We sort of blame ourselves. We figure well, you know, we knew what we were getting into when we had kids and so we’re just going to have to make do. We don’t see it as a system which is reliant on our labor as parents doing the very careful and important job of raising the next generation.

I think a lot of parents feel that isolation.

There’s an ideology that goes along with this where it’s really all on the parents. You are responsible. It’s almost as though kids are a luxury item as opposed to the next generation of our society. And because we blame ourselves we haven’t been able to create the political pressure to, you know, get Amazon to pay taxes so we can have a child care system in this country. Because if an individual employer says, okay, we’re going to have six months paid family leave they’re suddenly at a competitive disadvantage. So it’s very hard for employers to do that.

And so it seems clear we need a government-wide solution. But, right now, so many politicians are talking like social welfare programs are somehow evil. Can we get past that?

Well, we should look at solutions we’ve already had in this country. During World War II we needed women in the workforce. Suddenly. We were able to come up with childcare centers and extensive support. Also, we already have the equivalent of an allowance for children. If a parent dies Social Security gives income replacement so that the child will not be destitute. We have a system, you just have to die to get it. Still, socialist programs are not all that alien from things we’ve done in the US.

I’m watching President Trump shadow box with the idea of socialism in front of roaring crowds. Do you still think that’s true?

I think the fact that people are now complaining about socialism is a sign that we actually have made politicians understand these programs are politically viable in the US. They’re reacting to that political viability by denouncing it.

What’s the breaking point going to be?

By

pushing forward this idea that we’re on the informal birth strike,

people will start to get a sense of just how bad it’s gotten. It’s not

just an individual issue. This is something we need to have a collective

solution so our kids don’t have to go through this.