By Ann Schneider

The Indypendent

April 3rd, 2019

Issue 245

It took more than a decade of litigation by feminist plaintiffs for RU-486 (mifepristone), known as the “morning-after pill,” to be legally sold over the counter in the United States. The medication, which causes the pregnancy to be expelled, was fiercely opposed by anti-abortion forces.

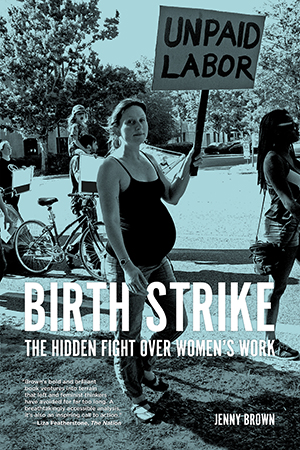

Why would opponents of abortion also want to keep birth control out of women’s hands? In Birth Strike: The Hidden Fight over Women’s Work (PM Press), veteran feminist Jenny Brown, a plaintiff in the RU-486 litigation, argues that record numbers of women are declining to have children because they do not have the social or government support — such as paid parental leave and universal healthcare — to raise children unencumbered. In response, she contends, the corporate patriarchy is trying to coerce them into having more children by reducing or eliminating access to abortion and birth control.

Fertility rates among all women in all major U.S. racial groups hit lows in 2018. The birth rate among Latinas, who have more children than either non-Hispanic whites or African Americans, fell from 97.4 births per 1,000 women in 2007 to 67.6 in 2017.

Who is that a problem for, Brown and her compatriots ask; why have states passed 668 restrictions on reproductive rights over the past decade? In Texas, 82 family planning clinics were shut down by pretextual regulations that made it impossible for them to function. The result, according to the New England Journal of Medicine, was that use of birth control went down and childbearing rose 27 percent for women in the affected areas. So who wants us to have babies against our will, and why?

Conservative New York Times columnist Ross Douthat has one answer: “Today’s babies are tomorrow’s taxpayers, workers and entrepreneurs. No babies, no consumer demand.”

Birth Strike supports its arguments with facts culled from a vast historical survey of the changing legal status of abortion, contemporary interviews, economics and germinal feminism — such as that of the Redstockings, the 1970s New York radical women’s group. In keeping with tried-and-true radical-feminist principles, it relies on testimonials of women who have faced the choice of whether to reproduce or not, and at what price.

That the United States provides so little support for mothering comes as a shock to most immigrants. Around the world, 185 of the 193 members of the United Nations provide paid leave for new parents, five of them for six months or more. Redstockings once organized a speak-out at the UN where women from Columbia, Cuba, Hungary, Costa Rica and elsewhere bragged about what their governments provided.

Keeping women’s reproductive labor unpaid amounts to profits for the 1 percent. It keeps the burden of parenting in the private rather than public sphere. The website Fatherly.com gave its review of Brown’s book the headline, “How Childless Adults are Secretly Protesting for American Parents.”

Given that reproduction rates are below the number needed to keep the population level, Brown concludes, “In the U.S., women have not yet realized the potential of our bargaining position.”

This is not “lean in” feminism. For radical feminists, there are no individual solutions. Rather, they say, tax wealthy corporations and individuals and their offshore tax havens to provide subsidized daycare for all children, and pay the providers (who are mainly black and Latina women) a sufficient wage. Birth Strike also demands the repeal of the 1976 Hyde Amendment, so Medicaid can again pay for abortion in all states.

Women’s refusal to carry children under current circumstances is an undeclared birth strike. Rather than looking at our physical capacities as a vulnerability or a disability, having the choice to carry a child can be a source of political power for women. This is a truly revolutionary realization.