By Michael Bilow

Motif

June 5th, 2019

Doctors among warriors occupy an unusual position in society, witness to much yet trusted and expected to respect confidences. The character Doc Daneeka in Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, 1961, defines the title that has become a standard idiom of American English. MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors by Richard Hooker, 1968 – the pseudonym of real-life military doctor H. Richard Hornberger – is a serious and dark comedy with forgotten religious symbolism that was mostly cut from the movie version, featuring incidents such as a mock crucifixion of the Protestant chaplain, a “Last Supper,” and a surgeon who conducts personal appearances and signs autographs as Jesus.

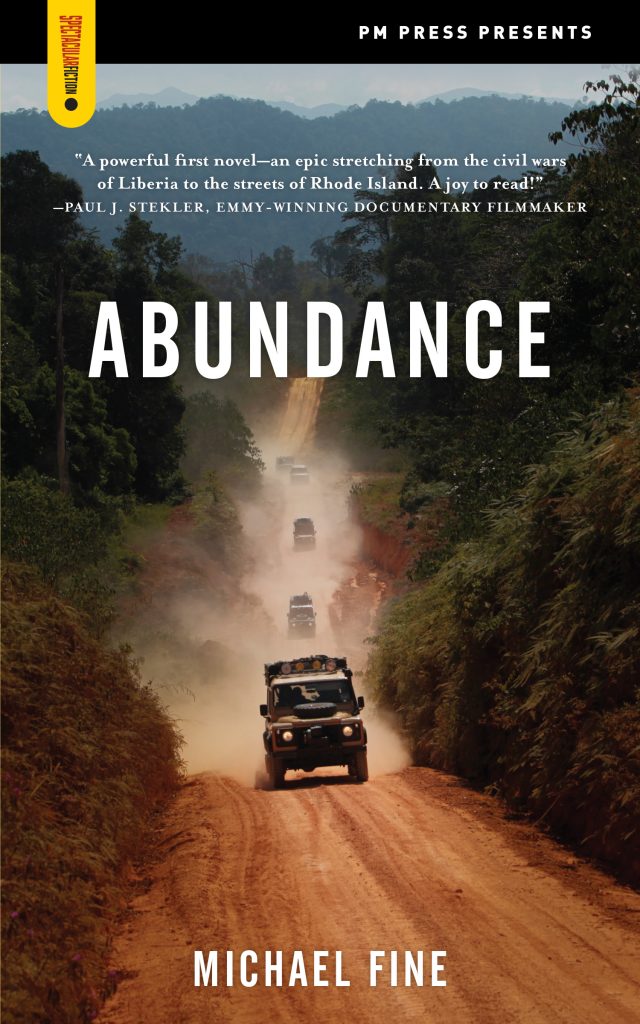

Michael Fine, a doctor whose 40-year career encompasses everything from serving as director of the RI Department of Health to practicing medicine in war zones in Africa, has written a gripping thriller informed by personal experience. “I’ve always thought of myself as a fiction writer. I’ve been writing fiction for a long time,” Fine explained why he published his first novel about a society in collapse. “The only way we’re going to fix this is with the imagination.”

Set amidst the wreckage of the Liberian civil war that ran in phases from 1989 to 2003, the novel centers on RI-based colleagues separated in the course of a “rescue” by US Marines, leading one of them, Carl Goldman, to head back to Liberia for an unauthorized rescue of another, Julia Richmond, enlisting the help of William Levin, an older doctor who is her mentor. Levin asks if Carl and Julia have a romantic connection: “‘Not exactly yes, not exactly no,’ Carl said. He paused. ‘More yes than no. Maybe more than that.’”

Fine is careful to supply cultural background. He includes a non-fiction preface explaining the founding of Liberia in 1820 by free blacks from the US, organizing the country along the model they know from home at the time, complete with these “Americo-Liberian” immigrants becoming de facto slave masters. Fine often employs dialect in “Liberian Kreyol, also called Liberian Pidgin, which is a trading language based on English and Portuguese that has been used for three hundred years,” and he includes a glossary. There’s even a non-fiction appendix that discusses, among other things, the rumors that brutal Liberian dictator (and subsequently convicted war criminal) Charles Taylor at one point lived in Pawtucket.

Fine told Motif the writers he most admires are “Tolstoy, probably more than anybody,” and I.L. Peretz, “who continues to live in my heart and soul” and “was a giant of his time” in Yiddish literature during its brief flowering in the late 1800s to the early 1900s who could, Fine said, “see through to the human values.” Fine’s English style has nothing of the supernatural succubi and holy fools of Peretz but, among that class of Yiddish writers, is more reminiscent of the worldly and modern I.B. Singer. “I once had the opportunity of hearing I.B. Singer speak when I was young and he was living on 86th Street in New York, although I actually heard him in Philadelphia,” Fine said.

Abundance is a realistic tour-de-force of survival in a failed state rife with warlords and child soldiers answerable to no one, where ordinary people struggle to get on with their lives in a society run by naked power exerted through machine guns. Fine’s skill as a raconteur makes the novel seem as if he is your personal tour guide through chaos and civil war, but with a very hopeful and optimistic outlook.

If you like this: Another America: The Story of Liberia and the Former Slaves Who Ruled It by James Ciment (336 pages, Hill and Wang, published August 12, 2014) and Madame President: The Extraordinary Journey of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf by Helene Cooper (336 pages, Simon and Schuster, published March 7, 2017).