A review of Michael D. Yates’ Can the Working Class Change the World? (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2018).

Since working-class voters have been made responsible for everything from Brexit to the rise of the far right across Europe to Trump in office, the left has rediscovered class. Among the many contributions made to relevant debates in the past two years, some have been very good, some very bad, and many very confused. This text is about one of the best.

The economist and labor educator Michael D. Yates has been a longtime associate editor of Monthly Review. He describes his background thus:

“By any imaginable definition of the working class, I was born into it. Almost every member of my extended family – parents, grandparents, uncles, aunts, and cousins – were wage laborers. They mined coal, hauled steel, made plate glass, labored on construction sites and as office secretaries, served the wealthy as domestic workers, clerked in company stores, cleaned offices and homes, took in laundry, cooked on tugboats, even unloaded trucks laden with dynamite. I joined the labor force at twelve and have been in it ever since, delivering newspapers, serving as a night watchman at a state park, doing clerical work in a factory, grading papers for a professor, selling life insurance, teaching in colleges and universities, arbitrating labor disputes, consulting for attorneys, desk clerking at a hotel, editing a magazine and books.”

In 2009, Yates’ book In and Out of the Working Class appeared, a collection of essays, articles, and stories about growing up working-class, entering academia, and teaching workers in labor studies programs. It is a fantastic, and often gripping, account that fleshes out impressions from the life of working-class leftists offered in publications such as Clenched Fists, Empty Pockets: True Life Experiences of Working-Class Activists in the Middle-Class Left.

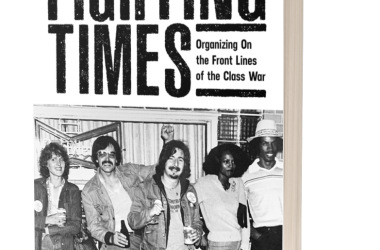

Hot off the press is Yates’ latest book Can the Working Class Change the World?. With change, Yates means a radical transformation of the economic, political, and cultural framework that shapes our lives: “Only radical thinking and acting have any chance of staving off accelerating levels of barbarism.”

Yates’ writing is very clear. The rules of capitalist production and class society are presented in ways that anyone can follow, no matter how many Marxist study circles or economics classes they have attended. Despite differences in focus and scope, the approach is similar to that of Torkil Lauesen in The Global Perspective, another recent book on global capitalism and the necessity to fight it.

A particular strength of Can the Working Class Change the World? is that the clarity doesn’t disappear as soon as the all important question of how to confront global capitalism arises. While many contemporary authors, apparently still under the influence of postmodern elusiveness, escape into hyperbole at that point, Yates doesn’t shy away from spelling out demands (from a “planned economy” to the “socialization of as much consumption as possible”), “arenas of class struggle” (from education to agriculture), and key targets of revolutionary struggle (racism and patriarchy). This distinguishes his conclusion from pompous revolutionary sloganeering:

“The conclusion I have reached is that fundamental, radical change, the kind implied in the title of this book, will not happen unless the working class and its allies attack capitalism and its multiple oppressions head-on, on every front, all the time. This is the presumption underlying this book. Struggles must be undertaken and coordinated against employers, the state, the mainstream media, those who run our schools, the police, the prison system, against racism, against patriarchy, against the destruction of the environment, against mega-church evangelicals, against the rise of fascism, against imperialism, and many other persons and institutions. Only such an all-out offensive has any chance of consigning capitalism to history’s dustbin. Only this can give us hope of building a fundamentally new society, one with grassroots democracy, economic planning, a sustainable environment, meaningful work, and substantive equality in as many aspects of life as possible.”

There is so much in this book I agree with, from including the peasantry into the working class to championing a “we” over an “I” approach, that it’s impossible to list everything. I will therefore limit myself to quoting one more passage, from the book’s very last page, in order to remind ourselves that we have no choice but to resist and work for revolutionary change, regardless of the odds:

“No doubt, it might already be too late. It will take time for a class riven with so many fundamental cleavages, by race/ethnicity, gender, and imperialism most importantly, to unify itself and destroy its class enemy. Mother Earth may take her revenge on us before that. In the meantime, though, best to do what we can, in whatever ways of which we are capable: by any and all tactics, everywhere, all the time, in every part of the capitalist system. Fight landlords, disrupt classrooms, take on bosses, write, nothing is unimportant. And as we do this, remember that those who have suffered the most – workers and peasants in the Global South, minorities in the Global North, working-class women everywhere – are going to lead struggles or they are likely to fail.”

Anyone who shares this belief will benefit from reading this book.

(October 2018)

More blogs from Gabriel | Back to Gabriel Kuhn’s Author Page