By Jason Christian

Los Angeles Review of Books

November 14th, 2024

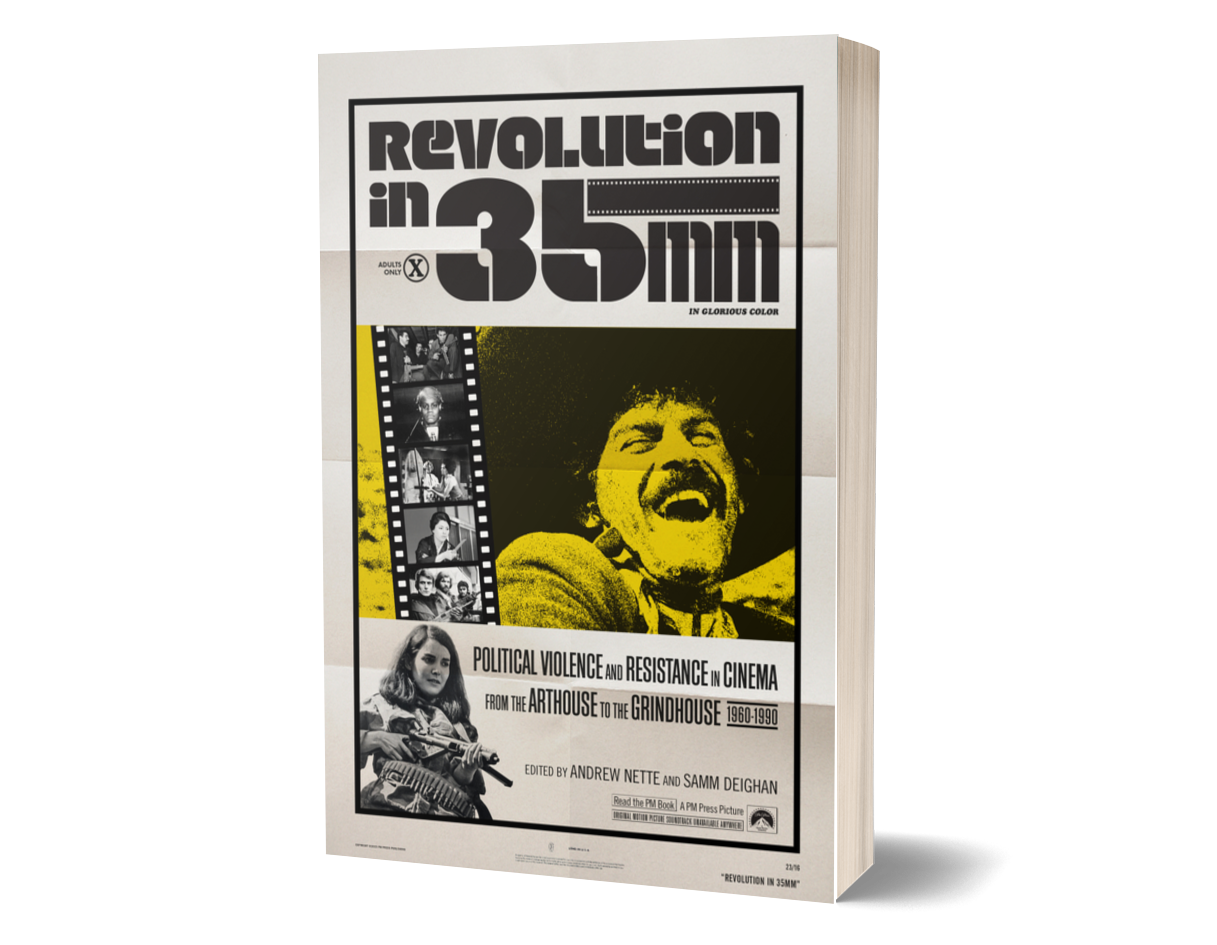

Jason Christian reviews “Revolution in 35mm,” edited by Andrew Nette and Samm Deighan.

IN MAY 1976, mere weeks after a brutal junta took over Argentina, a military death squad kidnapped the Jewish Argentine filmmaker Raymundo Gleyzer, and he was never seen or heard from again. Gleyzer had been a founding member of Cine de la Base, a revolutionary film collective in Argentina allied with Grupo Cine Liberación and other leftist film groups across Latin America, from Bolivia to Cuba. His final film, a narrative feature called Los traidores (“The Traitors,”1973), was a departure from his usual documentary mode. In it, Gleyzer dared not only to critique Argentina’s Far Right, but also to take aim at corrupt labor leaders who collaborated with them. “Gleyzer had been tortured, including having his eyes gouged out,” writes the scholar Andrew Nette. “After his disappearance, Cine de la Base rapidly dissolved.”

Gleyzer’s tragic fate provides a glimpse of what leftist filmmakers risked to make their work in Argentina around the years of the so-called Dirty War, the period of state terror from 1976 to 1983, during which the junta tortured and “disappeared” tens of thousands of people it considered a threat. Nette folds these details into an essay on Argentina’s New Cinema movement, one of nearly three dozen pieces included in the new volume Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960–1990. Co-edited by Nette and the film historian Samm Deighan, the book covers revolutionary filmmaking during the years coinciding with the height of the Cold War, which was nothing if not molten hot. During this period, decolonial movements exploded across Africa and beyond. The US stepped up its proxy war with the USSR in Cambodia and Vietnam. The CIA assisted with assassinations and the toppling of regimes in Chile and numerous other countries. American students on the left revolted against these conflicts, which they considered imperialist in nature, and against the repression that accompanied them at home. Various Maoist “urban guerrilla” groups formed in several Western nations, including the United States, engaging in terrorism and sabotage. And all this push and pull from empire and its enemies wound up depicted violently on-screen.

Nette’s essay on Argentine cinema is exemplary of the volume’s focus on how a new aesthetic vocabulary, informed by Marxist principles, developed in conversation with tumultuous events on the ground. In 1968, when the Argentine status quo was less murderous, the two writer-directors Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas released their magnum opus, The Hour of the Furnaces, a four-and-a-half-hour documentary that inspired leftist filmmakers for generations. The next year, the duo penned a manifesto, “Towards a Third Cinema,” coining a term for an emerging cinematic movement across the Global South—or Third World, as it was then called—and devising a theory for how to engage in revolutionary filmmaking in such repressive, volatile times. These filmmakers “sought to develop films that fused a new form of aesthetics with radical ideology and political practice,” Nette writes. “A central concern was the rejection of Hollywood, along with the exploration of cinema as a tool to help overthrow the region’s neocolonial mindset.”

Nette and Deighan have provided a highly readable sampling of radical-left global cinema for fans and scholars alike, one that offers the historical and political context needed to understand each film’s impact locally and often internationally. While the anthology is not comprehensive—that would take numerous books—it’s the most thorough single-volume companion on radical films of this period that I have come across. And since the issues explored within the 353 films mentioned in the book have never really gone away but instead have taken on different forms, the book demonstrates their continued resonance in our polarized and increasingly violent world today.

¤

The films in question represent every popular genre, from horror to science fiction, plus a few newly minted ones. Deighan, for instance, devotes several pages to Japan’s controversial sexploitation “pink” films, which emerged during the turbulent 1960s from disillusioned student activists-turned-filmmakers who formed part of the Japanese New Wave. Some of the other films discussed in the book similarly fall into the “exploitation” category, like the low-budget “girl gang” rape-revenge movies, which are brilliantly examined by Annie Rose Malamet. Others would be clearly categorized as art-house, including Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960s cinematic output, discussed at length by Deighan. The collection includes some deeply personal essays, such as “Ghosts and Weeds” by Greek Australian novelist Christos Tsiolkas, which explores the complex queer politics in Costa-Gavras’s political thriller Z (1969), as well as chapters focused on less canonical works. For instance, Nette examines the work of Gillo Pontecorvo, who is mostly known for his anti-colonial epic The Battle of Algiers (1966), but whose other films, such as Kapo (1960), Burn! (1969), and Ogro (1979), Nette sees as unfairly neglected (I happen to agree). The book is similarly ambitious in its geographic coverage: a number of national film movements are discussed in the book (e.g., Brazil’s “Cinema Novo,” as considered by Scott Adlerberg), as well as regional genres, reflected in Uday Bhatia’s essay on Hindi gangster films, for example.

What unites the films covered in this collection is their engagement with violence—whether they critique it, fetishize it, or both. Emma Westwood considers the symbolic victories of second-wave feminism in a compelling piece on the use of violence in three disparate films: Marleen Gorris’s A Question of Silence (1982), Lizzie Borden’s Born in Flames (1983), and María Luisa Bemberg’s Camila (1984). Robert Skvarla interrogates the notorious violence-for-violence’s-sake underground “mondo” films that enticed Western viewers with problematic “Third World” violence on-screen. Mike White explores Peter Watkins’s subversive “human hunting films,” Gladiators (1969) and Punishment Park (1971), and their various predecessors and heirs.

This shared emphasis doesn’t mean that historicopolitical realities were similar in each country—far from it. One of the book’s contributions is that it answers the question of how exactly these contexts were unique and how the material conditions of the films’ productions determined their cinematic representation.

Some of the more illuminating pieces address the financing of radical filmmaking and the impact of the resulting films both at home and abroad. Take Matthew Kowalski’s essay on the Yugoslav Black Wave, for instance. Yugoslavia’s most influential prime minister, Josip Broz Tito, helped found the Non-Aligned Movement and positioned his country as one of its primary representatives. (Although Yugoslavia was a socialist country, it would neither align itself with the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc socialist countries nor with the United States and the rest of the so-called “Free World”—or, rather, it partially aligned itself with both.) Along with this bold step, Tito allowed the importation of foreign cinema from nonsocialist countries. “It was in this strange incubator that the Yugoslav Black Wave took root,” writes Kowalski. “Direct exposure to foreign films (particularly American, French, and Italian) gave Yugoslav filmmakers a tool kit to challenge the formal constraints of state-sanctioned aesthetics.” While plenty of partisan films had been made after the Second World War—to both entertain and inculcate the masses with socialist ideals—this trend began to change “by the early 1960s,” writes Kowalski, when the “sanitized version of war was openly challenged by a host of young Yugoslavian filmmakers.”

Kowalski guides the reader through a host of examples, including Aleksandar Petrović’s Three (1965) and Dušan Makavejev’s W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (1971). Films like these, he writes, “were critiquing not just the Yugoslavian past, but also the contradictions of the nation’s present.” Moreover, they did so in a wholly unique way: by taking full advantage of their socialist education and remaining “firmly rooted […] within the ideological coordinates of the system itself.” Three was a “counterpartisan” film, Kowalski argues, with no identifiable heroes, unlike the heroic socialist realism war dramas that came before it. W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism, meanwhile, critiqued “both the United States and the Soviet Union […] for misdirecting sexuality into power politics and militarism.” The latter film was banned, but, like Three, it demonstrates how violence was used transgressively—not to condemn the state, but paradoxically to “[turn] the theory of Titoism into practice.” In other words, these filmmakers wanted, in a sense, to legitimize the state, and urge it to enforce the principles it claimed to possess.

Italy, a country next door to Yugoslavia, had to contend with a distinct social reality, as Nette reveals in an essay on political crime thrillers (poliziotteschi) from the late 1960s through the 1970s. In the decades after the fall of Mussolini’s fascism, the Left and the Right were vying for control of the government, and for the hearts and minds of the people. There was corruption at the top, the Mafia in the middle, and an incredible amount of violence in the streets. Those years are dubbed the “Years of Lead,” whose “most intense phase in the 1970s was bookended by two major events,” as Nette puts it: the bombing of a bank in Milan in 1969, perpetrated by the Hard Right, and the kidnapping and murder of the prime minister, Aldo Moro, by the ultra-left Red Brigades.

At the same time, Italy’s film industry was also churning out one bloody, thematically analogous flick after another, many of them well financed and widely distributed to the working class. Most American film buffs have probably heard of the Italian spaghetti Westerns, especially Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, but fewer are likely to know about the trend of “Zapata” spaghetti Westerns—films like A Bullet for the General (1966) and Long Live … Your Death! (1971), which depicts Mexico’s revolutionary period in a highly allegorized, often comic mode. In an essay on the subgenre, critic Lee Broughton points out that “Mexican characters functioned as racial palimpsests that spoke on behalf of both the Italian proletariat (particularly the dark-skinned southern Italians living in—or migrating from—the rural south of the country) and oppressed ‘Others’ worldwide,” whereas “their uniformed Federales and Rurales might be read as stand-ins for the repressive state apparatuses of any contemporary reactionary regime of choice.”

If B-Westerns didn’t suit one’s taste, Italian audiences had plenty of options, including the political satires of Elio Petri—revered in Italy and abroad for films like Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970) and The Working Class Goes to Heaven (1971)—or gritty poliziotteschi. The films Nette discusses “fused police procedural and hard-boiled crime tropes with attempts to uncover high-level political conspiracies and attempted coup plots, always far-right or neofascist in origin.” The populace knew unequivocally that their government was corrupt, Nette says, but these films gave them an opportunity to engage with the sober implications of this fact.

Perhaps this viewership was cathartic in some way, reminding audiences of cinema’s potential, or lack thereof, to inspire political action. Nette never ventures a guess, but he and the other writers throughout the volume suggest that these directors, especially the openly revolutionary leftist ones, like Pontecorvo, are grappling with the gains and costs of violence as a political tool. One might assume that audiences did the same.

¤

In Yugoslavia and Italy, the state and private investors, respectively, poured ample funds into cinema production. But what about countries where no such opportunity existed? Filmmaking is an expensive medium that requires teams of personnel with specialized knowledge. It also requires costly equipment and systems of distribution. Most countries under attack are not as generous as Yugoslavia was in those years before its ultimate collapse. And if the regimes in question are not interested in even pretending to be democracies, they might kill transgressive filmmakers, as they did Raymundo Gleyzer, or throw them in prison, like Iran has done with Jafar Panahi.

Most countries, however, turned to censorship. States around the world have banned radical cinema, and its surviving producers either gave up their craft or fled the country to continue working. For these reasons and others, most of the films covered in the book were made on a shoestring budget and at the margins. As Nette and Deighan make clear in the introduction, their “emphasis on these two strands of cinema [exploitation and art-house], rather than the mainstream film market, is because both provided more freedom of expression for filmmakers.”

One interesting exception to the financing and distribution problem was the Senegalese director Ousmane Sembène, as Deighan notes in an essay on Sembène and early African cinema. An internationally known writer and committed communist, Sembène was invited to Moscow, where he was taught the basics of cinematic craft and supplied by the Soviet Union with equipment to make his first films. (The same opportunity was given to the French Guadeloupean director Sarah Maldoror, who made the celebrated drama Sambizanga (1972) about the militant anti-colonial struggles in Angola, which Deighan discusses in an essay on her as well.) Sembène was first embraced by his country’s newly established postcolonial leadership even before the release of his debut feature, Black Girl (1966), a film that condemns, through its brutal depictions, French settler colonialism and the racism Senegalese migrants faced in France. But some years later, after Sembène turned his focus on the Senegalese ruling class—what Frantz Fanon called “the native elite”—the government banned his films. These films “center African greed and corruption in their narratives,” Deighan writes, “which are explicitly depicted as caused by colonialism [but] feature Black characters—namely soldiers, businessmen, and government officials—who subjugate other Africans.” This critique is especially showcased, Deighan points out, in Sembène’s critically acclaimed, but locally banned, trilogy: Emitaï (1971), Xala (1975), and Ceddo (1977).

Not to be dissuaded, Sembène showed his films anyway. He drove around the Senegalese countryside with a projector in tow, setting up screenings in back rooms for groups of villagers keen to learn and discuss these forbidden topics. Sembène called these events “night school,” according to Tsogo Kupa, whose essay for Jacobin is cited by Deighan cites: “They challenged patriarchy, critiqued Senegal’s political elite, sought to raise class consciousness, and unashamedly defended the notion that there was a cosmopolitan and pluralist culture indigenous to Africa.”

Sembène began his career as a novelist but soon realized that many of his fellow countrymen and women had never learned to read. This realization led him to turn to cinema as a more viable means of telling stories and relaying ideas. It was never in the cards for Sembène to make commercial cinema, and the epigraph Deighan uses to begin this essay—“Cinema is like an ongoing political rally with the audience”—suggests he didn’t mind.

¤

So far, I’ve left out the United States, which many of the films were responding to directly or by implication, merely due to the fact that US hegemony reached every corner of the globe. Nette and Deighan place American cinema toward the end of the book as well, perhaps out of deference to lesser-known global cinemas, or perhaps to acknowledge its relative influence compared to the other cinematic movements already discussed.

By the early 1960s, Hollywood had weathered the second Red Scare and no longer found it useful to enforce the notorious “blacklist” of suspected communists working in the industry. But the industry was still hesitant to wade deep into leftist themes. Furthermore, the mainstream critical media landscape considered such films passé. “Critics were often quick to dismiss politically oriented films,” writes Kimberly Lindbergs in a chapter on “campus revolt” films, and were “habitually mocking their efforts to reach a younger audience and deriding attempts at artistic experimentation.” Nevertheless, several American campus-revolt films were made during the Vietnam War era—though notably, the best known, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970), was directed by an Italian. Reactionary MGM employees went out of their way to hinder the film’s production, according to Lindbergs, and “the FBI tracked and harassed the cast, as well as some crew members.” Despite these and other attempts by the industry and government to sabotage the film, it did get made, and the result was spectacular. “Zabriskie Point is a modern masterpiece,” writes Lindbergs, “that still resonates today because the problems the film illuminates—political apathy, police violence, easy access to guns, disregard for human life, rampant consumerism, and our inability to form a more perfect union—are still with us today.”

Haskell Wexler’s cult film Medium Cool (1969) offers another example of American cinema’s engagement with radical-left activism at the time. The film takes place in Chicago during the summer of 1968 and captures, with a cinema vérité style, the chaos and police brutality at the Democratic National Convention that year. The film was countercultural, but it was still a Hollywood production, and received mixed reviews. Other films of this nature—such as Stuart Hagmann’s Strawberry Statement (1970)—were largely commercial flops. “Student activists criticized the films for being too commercial and trivializing the movement’s political aims,” writes Lindbergs, “while the general public didn’t seem particularly interested in watching films that dramatized the daily news headlines.”

At the same time, an underground film movement emerged in the United States alongside widespread social unrest. The films were propagandistic and, consequently, wholly uninterested in mainstream appeal—a point Nette explores in a short piece on the nearly forgotten Robert Kramer film Ice (1970). As a founding member of the propaganda production collective Newsreel, Kramer used his films as a radical teaching tool, exploring the logistics of how a revolution might actually take hold, and “he did not shy away from depicting the left’s problems and failures.”This work might have had its fans among radicals, but its Hollywood counterparts never enjoyed such praise.

One radical Hollywood film that did find a mainstream Black audience was Ivan Dixon’s The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973), based on a novel by Sam Greenlee. The film was categorized as blaxploitation, exempt from commercial imperatives shackled to white-coded films, which allowed the screenwriter and director to make a truly revolutionary film right beneath the noses of the studio executives. The film concerns the first-ever Black CIA agent, who hatches a plan to use his training to foment a Black Marxist insurrection of the sort the Black Panther Party dreamed about before they were crushed. The FBI caught wind of the film and sent a memo to then–California governor Ronald Reagan, warning him that the film could “further racial discord and disorders in this country.” United Artists was forced to fulfill its contract and release the film in 35 cities, writes Michael A. Gonzales, but shortly thereafter, it was pulled from theaters, “and it wouldn’t be released on video until nineteen years later.”

Notably, The Spook Who Sat by the Door received a 4K restoration this year, which premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York. There is no doubt that its concerns are as relevant today as they were in 1973. In fact, 2024 has been repeatedly compared to 1968: police brutality is still central to the discourse around structural racism and abuse of power; as in 1968, this year’s DNC was held in Chicago; student protests erupted across the country and were violently quelled by police; the current Democratic administration is backing a genocidal war in Palestine, reminding many of LBJ’s disastrous escalation in Vietnam. Apart from a few exceptions—like Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah (2021), about the betrayal that led to the assassination of the Chicago Black Panther leader Fred Hampton—American cinema today doesn’t seem interested in tackling these topics. Not that these movies are found in abundance anywhere—we tend to turn to the documentary for such sober subjects these days. But should we want to see fictional representations of revolutionary politics, we can track down those gems made half a century ago and grapple with their complexities as we try, against creeping cultural malaise and constant distractions, to imagine a better future.

Jason Christian is a writer and co-host of the podcast Cold War Cinema. His work has appeared in The Bitter Southerner, Full Stop, Gulf Coast, and many other publications.