By Andrew Major

Bike Mag

Jul 25, 2024

It may surprise you that Sam Tracy’s book ‘Riding More with Less – A Future for Bike Repair’ is not (just) about converting every bike to a single-speed. It ranges in topics from how to tighten a quick release, to disc brake pad materials, the history of pedal wrench interfaces, Brompton anti-rotational locknuts, and a long treatise on removing seized seat posts. If you already like working on bikes, you will probably enjoy it.

Sorry, Sam

I strongly disagree with the jacket claim that “Riding More with Less is the bike repair manual for everyone else.” If you jump into this book from raw hoping to learn how to work on your bike, you are in for 247 pages of disappointment. Yes, it is chock full of interesting insights, useful technical information, and even a taste of community bike shop philosophy. But, if you truly want to learn to wrench on your two-wheeled miracle machine you will be much better served by one of Lennard Zinn’s books on the Art of Bike Maintenance.

It is not that Riding More with Less does not cover many beginner-esque bicycle maintenance tasks, but it does so in a way that makes it exceedingly obvious that an experienced bike mechanic is writing it. The most obvious example of this is a multi-page introduction to tools that includes no photos beyond a folding work stand and a wheel truing rig.

This is not to say that the book is not entertaining, or interesting, or even important. I would simply only recommend it to folks who already know their way around a tool kit. I see it as a guide from an experienced city wrench to help a junior tech or home mechanic increase their bicycle service IQ. And I see it as a window into the world of community bike shops for anyone with time on the tools. I would go as far as to say, that while Sam Tracy authored this book, I read it with the voice of many of my mentors in my head.

Who Is Sam Tracy?

According to his bio, Sam is a writer, wrench, and “former bike messenger,” though I maintain that when it comes to the latter there is no such thing. Maybe it is unfair of me, but I cannot help imagining him as the aggregate of a couple of bike mechanics I have worked with.

Perhaps you know the type? They seem to subsist on nothing but smoothies – a sugarless arabica blend until 5-pm and then a Bavarian mix of barley, hops, and yeast afterward – and it is an event when they wear something that is not black.

When they come mountain biking with you, they are on one of three specific bike varietals. An immaculate decade-plus old hardtail. A current model year full suspension bike that “technically belongs to the shop.” Or a cobbled-together mishmash of parts on a recent-generation high-end carbon full suspension frame that was definitely supposed to be destroyed as part of a warranty claim.

As evidence of this profile, I will point the reader to Sam’s opening paragraph, which could have been written by any number of longtime mechanics I know if they were tasked with writing a do-it-yourself repair manual:

“When your bicycle needs repair, it may be simplest to visit your friendly local bike shop for their service and expertise. They probably deserve our support – precious few strike it rich fixing bikes, and our business helps ensure their continuing presence – but there might be other options as well. Given the time and inclination, odds are good that you can learn to fix it yourself.”

Is It Always About Single-Speeding?

In their writings about philosophy, the authors Cathcart & Klein have a fantastic one-liner that sums up every single speeder’s smiling invitation to join in pre-selected suffering: “A sadist is a masochist who follows the golden rule.” Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

Sam’s section about drivetrains ranges from a discussion of bottom bracket standards to freewheels & friction shifting, narrow-wide chainrings, and their incompatibility with front derailleurs, and even a reference to buy-once-cry-once in recommending sealed-bearing pedals should they be a financial option.

Waiting here, on page 210, is the crescendo to the seraphic symphony. The big Holmesian reveal. Elementary my dear bike mechanic slash rider:

“Our journey through the drivetrains leaves us better positioned to appreciate the single-speed bikes.”

Of course, everything in Riding More with Less is from a more urban perspective much of the focus is on single-speed conversion (which “do not necessarily turn bikes into unicorns”) and the increased tolerance for worn components or overcoming “exigent problems, such as nonfunctional shifting” and even covers in great detail salvaging cassette spacers and ditching vestigial chainrings.

Requiring similar frame considerations, there are also multiple pages dedicated to planetary (internally geared) hubs. I have limited experience with these systems and enjoyed Sam’s writing on the subject; however, speaking to my above section ‘Sorry Sam,’ I would not have enjoyed his writing without my basic understanding of the products.

[Single Speed Aside]

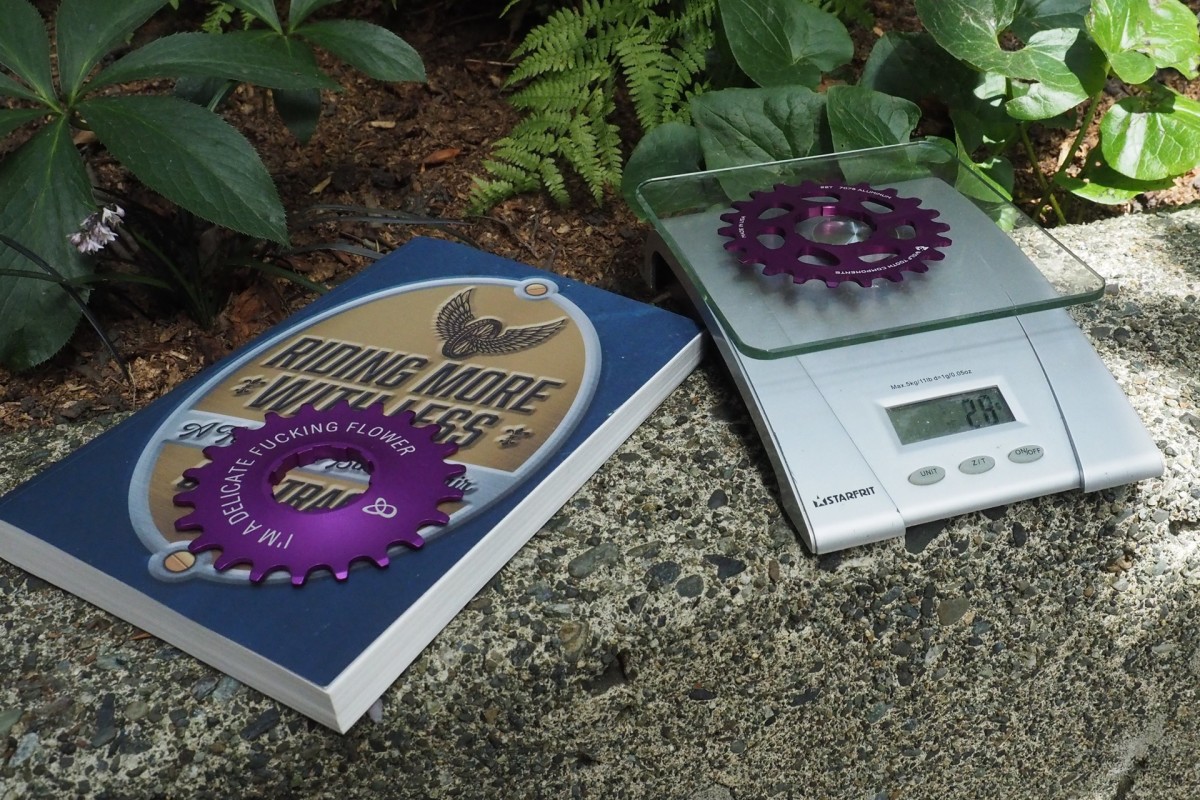

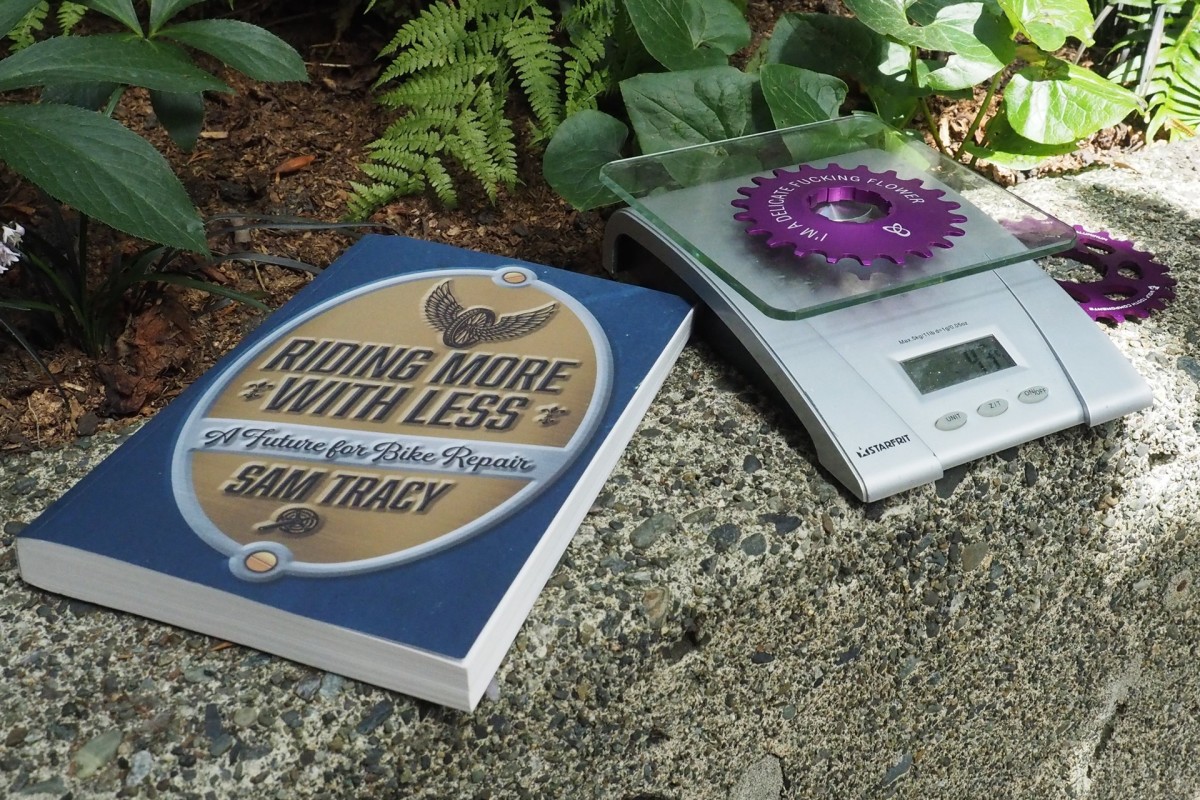

My test-writing vice is reviews-in-reviews but in this case, it is also an opportunity to break up the text of this book review with some photographs of this lovely Wolf Tooth 7075 aluminum cog. Like many single speeders who have been at it a while, in the days of 26” bikes I used beautiful, high-end, high-cost, stainless steel Chris King cogs that were practically machined to gossamer. These were sadly discontinued years back and even then, the largest one I ever managed to buy was a 20-tooth, which, while I still have a rideable one, does not suit my penchant for bigger wheels, bigger tires, and heavy inserts with on the steep and tight single-track climbs and the janky old-school-Shore descents I prefer.

Even riding year-round in some tough weather conditions, I have had excellent durability experiences combing high-quality 7075 aluminum cogs – Wolf Tooth, Endless, and others – combined with top-end 11-speed chains. A note here about materials is that many single-speeders will preach steel-is-real when it comes to cogs but in most modern cases the shitty steel that cogs are machined from only adds the benefit of being cheap. The cogs are heavy and crap out way faster than a high-quality 7075 unit.

For my off-road gearing needs these days it is 22t X whatever front ring suits. Usually, a 30t overall or 32t round on my mullet. I also know several riders running high-quality 7075 cogs in much smaller tooth counts who have had similar excellent durability results. My one piece of feedback for Wolf Tooth is that it would be nice to see some larger sizes. I know a few folks riding 23t, 24t, and 25t cogs on their one-speed 29’ers, Fatbikes, and other adventure craft.

The Wolf Tooth cog featured here has a notably narrower base than my standard go-to, the Endless Bike Co Kick Ass Cog, and thanks to being thinner and a significant amount of machining it is notably lighter weight. Even accounting for adding one more thin-spacer to my single-speed stack. I am not much of a weight weenie but in addition to the cog being very durable, I have not noticed any increase in wear to the aluminum freehub body on these Project 321 G3 hubs.

Wolf Tooth’s Single Speed Cogs are lightweight, machined in Minnesota, durable, and come in a pile of anodized colours for US$55.

[/Single Speed Aside]

Dynamo

What is a modern book about bicycle repair, written by a bicycle mechanic, without a couple or few sci-fi references thrown in? Sam writes “Were our hubs TIE fighters from Star Wars, their flanges would be the wings” and it occurs to me that it’s strange that I have never seen a SON Dynamo hub painted up in Imperial livery.

It is quite surprising that in the myriad pages about wheel building and hubs and even less common tech like drum brakes or multiple pages discussing cantilever brake cable-hanging, chainring bolt circle diameters (BCD), and even the Schlumpf Drive gets a mention, there is no talk of dynamo hubs. Dynamo lighting is a perfect solution for riders who need front and rear lights for safety but have a poor track record of remembering to top-up, or even bring their rechargeables. From the perspective of amortizing one’s life, a good dyno-lighting system can easily pay for itself compared to replacing rechargeables. Just ride your bike!

Sam even includes multiple pages on e-bikes, which at best are doing more with more, which makes this omission seem purposeful. It may be that it comes down to space, but I would have cut the paragraph on how to make brake pads last longer by coasting to a stop first. Maybe a chapter on dynamo generators in the next edition?

RUST!

“Corrosion may be more or less of a problem for you… Nobody’s truly safe, though. The tide may even have turned by the time your chain begins to squeak: your seatpost or bottom bracket might be seized in place already.”

Chapter XIII, on the fine art of rust prevention, is the most interesting. Here again, it is not that the tasks, from greasing contact points to spraying Frame Saver inside a frame, are beyond a beginner mechanic’s abilities it is simply written from the perspective of “We shop rats.” I mean, Sam references the Hozan C-358 fixed cup tool. If you know a bike shop that owns one, they either do or did, a lot of service work on loose-ball bearing bottom brackets.

In actual fact, without a moment’s disrespect, the acknowledgments page could just be condensed to read ‘My Fellow Shop Rats’ and it would sum things up perfectly.

Indeed, ‘RUST!’ is clearly the chapter that Sam most enjoyed writing, and, perhaps, it was even written before the others. It contains his most fluid poetry:

“The rusted bolts are often smaller problems, in that they rarely prevent us from sitting on or pedaling the bike, but they’re also our Cassandra figures…”

“The bonds of rust may have already outstripped the strength of the bolt…”

“It’s as if you’re carving out a tiny bowl, scraping its sides only when you need to, always aiming back to the deepening pit. The purpose of this exercise is merely to blaze a trail for one of the various easy-out bolt extractors, the splines of which burrow into the seized bolt as a means to corkscrew it back out.”

Riding More with Less

I imagine that Sam Tracy has been called, affectionately, a ‘Shit Bike Wizard’ more than a few times in his life. He might even have an SBW patch on his messenger bag. If you are familiar with bike repair but have SBW aspirations this book is a wonderful place to start. Likewise, if you own a copy of Zinn & The Art of Mountain/Road Bike Maintenance and want to supplement the everything-is-new and diagramed approach, Riding More with Less is a nice combination of grit and history.

To true the wheel that I started lacing at the top, either the “everyone else” that this book is purported to be for is a significantly smaller group than I would have assumed, or it overclaims its potential audience. It is, as claimed, both “info-rich” and a “technical discussion” and it certainly sets the reader on a path of considering creative solutions to mechanical issues.

If that sounds like it is up your alley(cat), I am positive that you will enjoy it and you will be spending US$25 with an independent publisher – PM Publishing – and to a fellow cycling-passionate bicycle-nerd and wrench.