By Bill Littlefield

ArtsFuse

June 1st, 2024

The graphics in “The Warehouse” provide clear explanations of a grim reality. The U.S. leads the world at incarcerating its citizens.

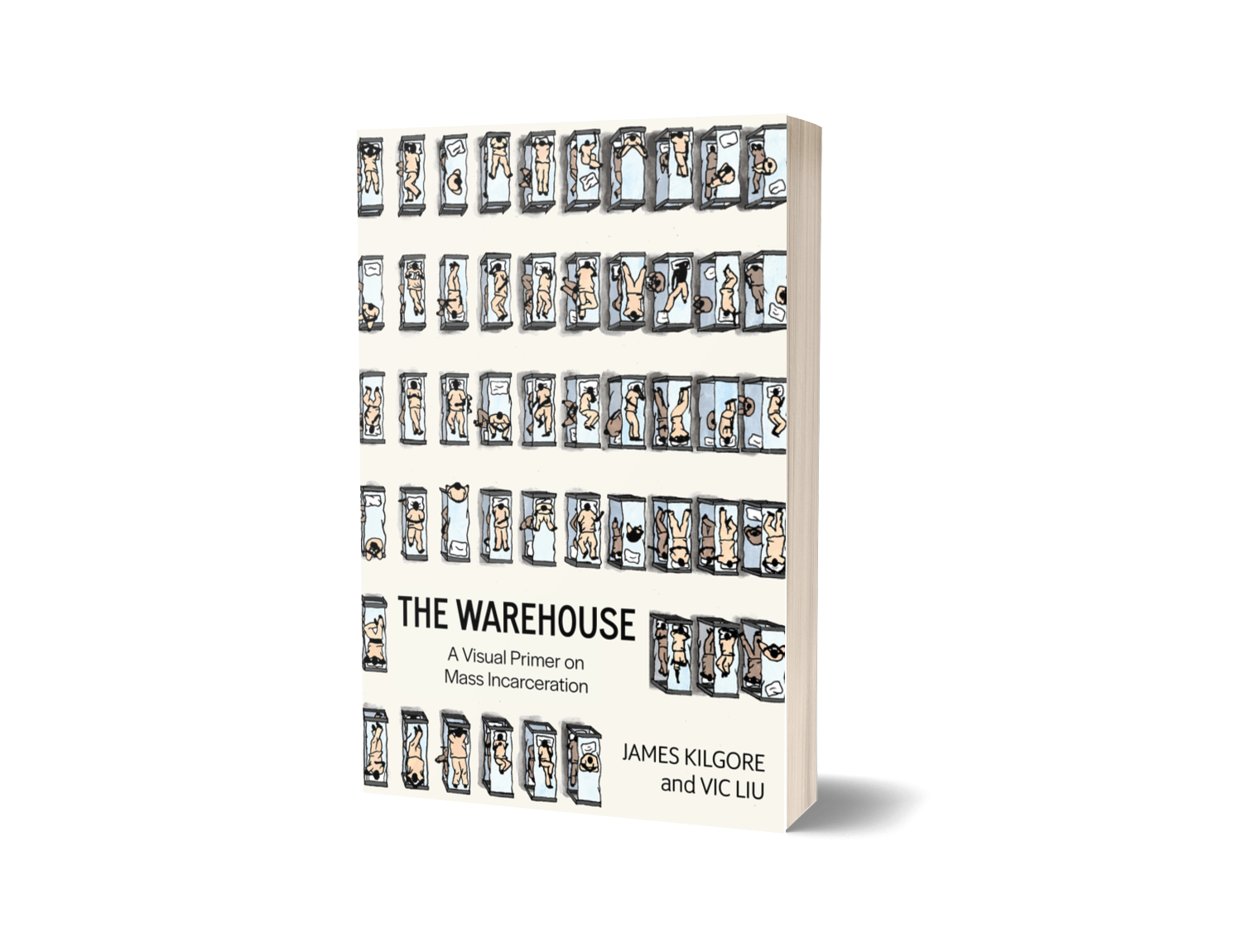

The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration by James Kilgore and Vic Liu. PM Press, 189 pages.

Many of the statistics available in The Warehouse will be familiar to anyone conversant with incarceration in this country. Black people are five times more likely to be incarcerated than white people; Native people are three times more likely to be incarcerated than white people; Latinx people are twice as likely to be incarcerated as white people. LGBTQ+ people are incarcerated at a rate three times higher than the general adult population.

That said, other stats here will be less familiar: Nearly two in five people in prison have at least one disability. People in prison are three times more likely than people outside of prison to have to live with at least one disability. In 2019, the population incarcerated in women’s facilities was seven times the size of that population in 1980.

The Warehouse provides clear explanations for a grim reality. The U.S. leads the world at incarcerating its citizens. Some of these reasons are economic. When the government reduces spending on social services and cuts programs that feed and house people, incarceration rates go up. When politicians create solutions to problems that don’t exist, such as when they speechify about getting tough on crime at the same time that crime rates are decreasing, incarceration rates go up. When politicians pump up their base by declaring war on some people who use some drugs, incarceration rates go up. When immigration is essentially criminalized, incarceration rates go up. When poverty is essentially criminalized, incarceration rates go up.

The Warehouse makes these points and many others with graphics. One of the more impressive of these is an ambitious timeline that pictures the war on immigrants. The historical markers not only include 1619, when the U.S. began enslaving men and women from the African continent and other obvious low points in this nation’s history as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1848). But there are also markers for the creation of detention centers during Ronald Reagan’s administration and the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994), which enabled U.S. interests to buy up land in Mexico, thus displacing farmers and workers. Then, of course, there was the Mexican War (1848), which made millions of people into immigrants through the redrawing of boundaries in what is now much of this country’s southwest.

Another powerful argument made by Kilgore and Liu contends that the carceral system in this country is built to make it extremely difficult for men and women who have served their sentences to return to life outside the walls. As The Warehouse points out, “there are more than 45,000 state and local laws that limit the freedom of a person with a felony conviction.” These restrictions limit freedom of movement and association, housing options, and access to basic services. For example, formerly incarcerated people often must pay for the devices they’re required to wear, such as monitors. If they can’t find work and miss payments on the device, they can be sent back to prison. The bias of the system is as clear in this respect as in others. As one of the book’s informative graphs demonstrates, Black men are more likely to be unemployed after they’ve been incarcerated than are white men, and the same holds true for women.

A page from The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration.

Toward the end of The Warehouse, the authors discuss the arguments for reforming the current system and the controversial issue of abolishing prison altogether. They define briefly some of the strategic alternatives, such as the restorative justice approach, which is built on the idea that the person who does harm can acknowledge the damage and take some action toward repairing it, assuming the person harmed can accept the arrangement, and transformative justice, which is based on the notion that the most harm results from “the unjust way society functions.”

The Warehouse is a clear, useful, and accessible starting point for anyone who wants to begin to understand how twisted and unjust is the system that cages millions of people in this country.

Bill Littlefield volunteers for the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent novel is Mercy (Black Rose Writing.)