Review by John Galbraith Simmons

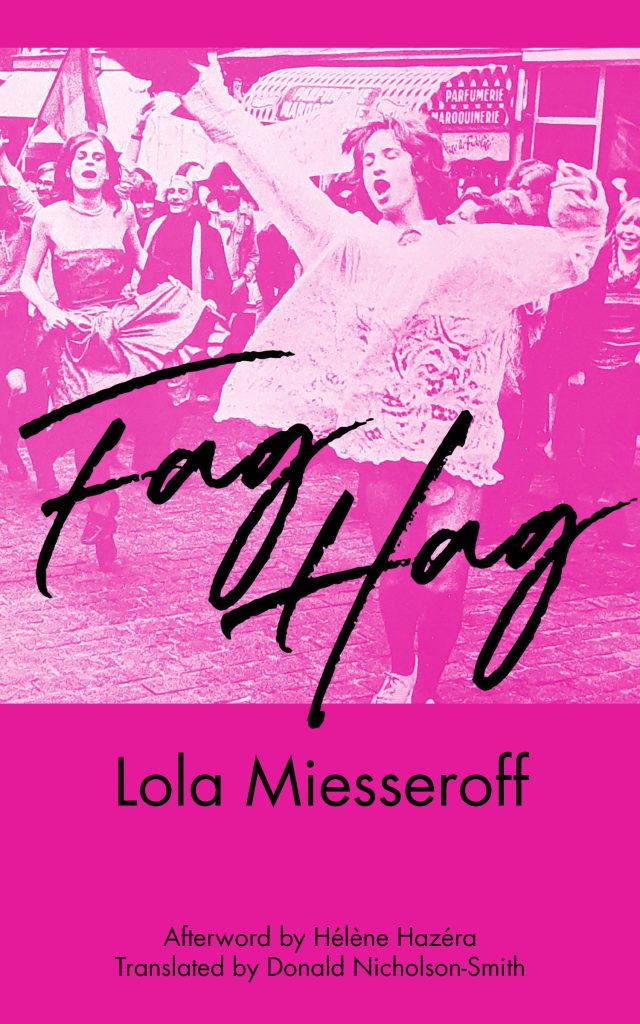

In the 1960s a small number among the young and alienated in France set in motion a revolt that took aim at political and cultural life in ways that set the stage for a permanent, ongoing critique of everyday life. Sex and sexuality, in this ambitious endeavor, constituted a central theater of engagement that has never since gone dark. As a testament to its early days Fag Hag, Lola Miesseroff’s lively and intriguing memoir, is as cool, collected and trenchant a guide as we’re likely to get.

Born shortly after World War II to Russian emigrants who settled in Marseilles, Lola grew up in a small world marked by far left-wing politics that made her readily receptive to a milieu that sang odes to free love. Her parents were radicals with an anarchist bent; both nudists, they established a naturist camp in the late 1940s and constituted a “tribe” that included all sexual shades and colors. Such that in childhood, as Lola writes simply, “I formed no notion of ‘sexual orientation.’”

Thus “de-gendered” but endowed with acute intelligence and a strident personality, she arrived at the university in Aix-en-Provence in 1965 on the cusp of the sexual revolution. It was soon to be a moment of inflection for political engagement by students amid gathering opposition to France’s colonial wars in Indochina and Algeria, the bankruptcy of Gaullist politics, and the dead weight of the French communist party. The nationwide uprisings of 1968 would not be far behind.

Lola, who is also author of an oral history Voyage en outre-gauche : Paroles de francs-tireurs des années 68 of the ultra-left in France during the 1960s, recounts her involvement in a blend of anarcho-politics and nonconformist activism, avant-garde Situationism and crazy lifestyle experiments. Her own brand of pansexuality did not involve existential agony or soul-searching; rather, she was naturally extravagant and writes that “I seemed to be a magnet to men-loving men.” Hence her memoir’s title. But she loved women as well as men. One of them, Hélène Hazera, provides a post-face and describes Fag Hag a “precious collection of recipes for freedom, a fine guide to combining political activism with personal liberation.”

An accurate assessment, for Fag Hag provides engaging brief portraits and snapshots of the left-of-left side of everyday life in the late 1960s. After leaving the university, Lola became part of a little demimonde “rife with pédés and gouines” and she paints memorable and often sensitive portraits, albeit brief, of the characters in her entourage. She doesn’t flinch, either, from detailing the dangers of gay cruising at the time or some of the sordid and painful stories that went with it.

As for herself, Lola developed a personal style replete with big hats, fishnet gloves, and a pre-Goth chalk-white complexion blessed with a fur muff in winter. She readily became part of the counterculture that emerged in France. Her comrades were anarchists or libertarian communists, often influenced by the politics of Situationism. In activist battles Lola and her friends contested at every turn the frequently bourgeois roots of left-wing currents, including the advent of second wave feminism and reappearance of older-fashioned Marxist politics, tinged if not infused by dyed-in-the-wool Stalinism. Noting the fashionable surge of Maoist politics in the late 1960s, one of Lola’s most charming anecdotes recalls her friends the Gazolines, a tiny group dedicated to far-left mayhem. This agglomeration of queens and transvestites showed up at the funeral of Pierre Overney, a murdered militant whose proletarian hero status enabled Maoists to fundraise gangbusters off his tragic death. As thousands attended his funeral (including Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault), the Gazolines joined the funeral cortege as obstreperous weepers, gay and loud, winding their way to Père Lachaise cemetery.

Told with gusto and steeped in revolt, Fag Hag with its tales of general subversion serves up multiple antidotes to the conformist currents that underlie today’s fragmented identity politics and threaten the very spirit of rebellion that’s essential to any hope of revolutionary transformation in the name of human freedom.

Translated with pure brio by Donald-Nicholson Smith.