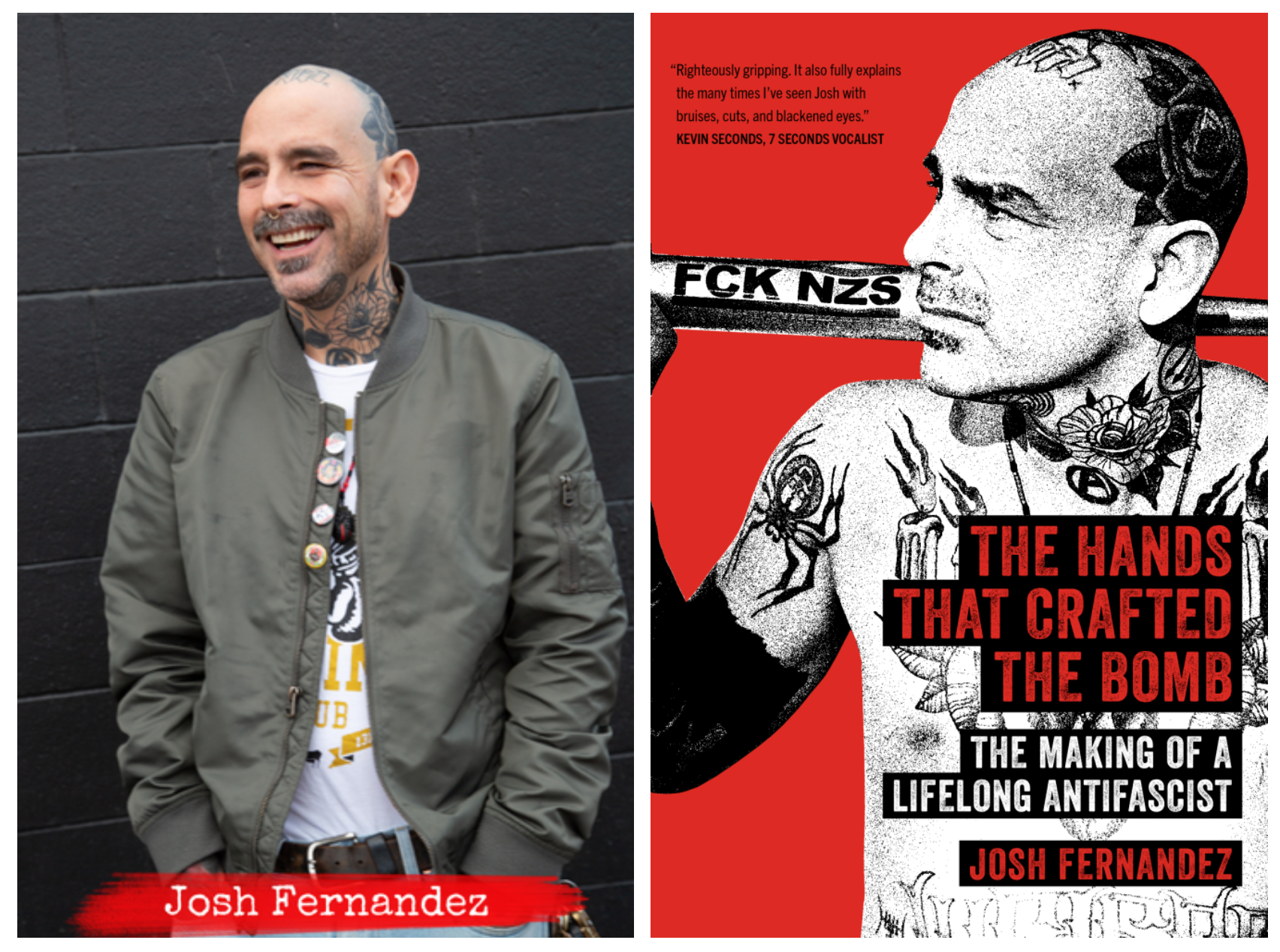

Josh Fernandez discusses his memoir, “The Hands That Crafted the Bomb: The Making of a Lifelong Antifascist.”

by Mel Buer

Real News Network

February 15, 2024

As a community college professor, Josh Fernandez started an anti-fascist club to organize alongside his students. The school administration responded by investigating him for “soliciting students for potentially dangerous activities.” Fernandez’s autobiography, The Hands That Crafted the Bomb, follows him through a year spent defending his job and reflecting on his political development from an angry young man in Davis, California, to a seasoned anti-fascist and writing professor. Fernandez speaks with The Real News about his life and recent book.

Post-Production: David Hebden

Transcript

Mel Buer: Welcome back, my friends, to The Real News Network Podcast. I’m your host, Mel Buer. Before we get started on today’s episode, I wanted to take a moment to thank you once again, our listeners, for listening to us week after week. Look, we know you’ve got limited hours in the day. Whether you’re listening to us in traffic, have us on your regular work pod rotation, or wind down the day with us, The Real News Network is committed to bringing you ad-free independent journalism that you can count on. We care a lot about what we do. I care a lot about what I do, and it’s through donations from dedicated listeners like you that we can keep on doing it.

Please consider becoming a monthly sustainer of The Real News Network by heading over to therealnews.com/donate. If you want to stay in touch and get updates about our work, then sign up for our free newsletter at therealnews.com/sign-up. As always, we appreciate your support in whatever form it takes. On this episode of The Real News Network Podcast, I was fortunate enough to sit down with Josh Fernandez, an anti-racist organizer, writing professor, runner, and fighter, whose book, The Hands That Crafted The Bomb: The Making of a Lifelong Antifascist, was released at PM Press on February 13, 2024.

The Hands That Crafted The Bomb chronicles the decades-long journey that Josh took to come to terms with the unbridled, anti-authoritarian rage simmering just underneath the skin, and the steps he took to channel that rage into something beautiful. It is raw, it is brutal at times, and it gives readers a completely open look into the imperfect life of a lifelong anti-racist and educator. I read the book in a day, it is that good. I’m so excited to have Josh with us to talk about his book, his life, his anti-racist politics, and the joys of writing in higher education. Neoliberal politicking be damned. Welcome to the show, Josh. Thanks for coming on. Can you tell our listeners a little bit about yourself so we can get acquainted with you?

Josh Fernandez: Yeah, sure. So I’m a community college professor. I teach writing. Half of my load I teach in the prison system, so a couple of my classes are at Mill Creek State Prison here in Northern California. I’ve been an anti-racist organizer for most of my life, starting with anti-racist action back when I was a kid and continuing to this day. So that takes up the entirety of my life. I’m married with two children, so growing up in this weird ass world we live in I’m trying to teach them some of the things I’ve learned along the way in terms of anti-racist organizing and trying to bring that into my classroom a little bit – Which has been a struggle – And trying to write as much as I can.

Mel Buer: So you are publishing this book, The Hands That Crafted The Bomb: The Making of a Lifelong Antifascist. It’s a memoir. Is this your first publication?

Josh Fernandez: Yeah. I have a book of poetry that came out in 2011, but this is my first full-length memoir.

Mel Buer: What was the process like putting this together? For those who will pick up this book… Because this book is released – We’re recording this on the eighth – Next week, on the 13.

Josh Fernandez: Yeah, the official date is February 13.

Mel Buer: So for folks who will pick this book up, it is a very raw, very emotional memoir. It’s very in your face with no mincing words about what your life was like growing up and moving your way through multiple addictions and some pretty brutal violence in your life before landing where you are now. What was the process like picking through those memories and trying to make sense of the last 30-40 years of existence?

Join thousands of others who rely on our journalism to navigate complex issues, uncover hidden truths, and challenge the status quo with our free newsletter, delivered straight to your inbox twice a week:

Josh Fernandez: Yeah, it was brutal. It was really brutal. I started making notes while I was going through this investigation that my school district was putting me through. And the notes were full of rage and I was trying to get back at the people who were putting me through this investigation. I wasn’t thinking of a book but I was thinking, okay, writing has helped me throughout all these times in my life. I’m going to write a list down and see what happens with this list.

I started writing these stories of my life and bringing them up, dredging up the past. You know what I mean? And I’m like, wow, there are a lot of weird stories that I have here that contribute to this person I am today. So it was brutal. Writing it wasn’t so brutal but it was going back and thinking about all this stuff again, that was the brutal part. It was traumatic to relive everything.

The book has this interesting framing, which is the investigation that your administration put you through for over a year while you were up for tenure at the community college. This is during 2017, 2018, and 2019, the post-Charlottesville craze of a red scare against Antifa – Which you and I both know is anti-fascist organizers – Which saw, not just on your campus, but many people who were investigated in higher ed for potentially leading their students into dangerous or violent situations. I know they had some similar things happening at Berkeley and other universities.

So it’s this interesting portrait of what higher education politicking looks like and what a lot of professors and higher education professionals come up against. I appreciated the very clear-eyed look into how administrations can react to people that they view as dissonance, really. Even though they do get hired on for their, for lack of a better term, “renegade quirkiness.” They say, well, you’re an asset to this education because we believe in the diversity of opinion, of knowledge building. You got tattoos, you’re going to fit in with these kids. And then they can turn on a dime. What did that feel like? How long were you at the community college before you were up for tenure? At least a couple of years, right?

A couple of years, yeah. I was there for a couple of years as an adjunct and then they hired me on. I felt really stupid because I was so naive when I went in and I’m like, here’s this progressive institution of all these leftists who are down for the cause. We might believe differently, and we might have different tactics, but we’re all pointing in the same direction. So when they offered me the job, I was happy and I was blinded by the brilliance of a full-time position at a college. I went in marching around.

Looking back I’m like, what an idiot. Why would I think these people are on my side at all? Do you know what I mean? Because when I analyze it, when I look at some of the things they were saying to me and the investigation that they eventually did on me, we didn’t believe the same things. These are neoliberal hacks who say things, don’t believe them, and then go crawling back to the bank to pray to that God. Do you know what I mean? So it isn’t about the progressive politics that they say it is; It’s about the buzzwords and then bowing to the gods of the institution.

Mel Buer: I’ve had the privilege to speak with a lot of educators over the last couple of months who are leading the charge in this newest battle against Zionist propaganda on college campuses. And I’m always really struck by these folks; Some of them who don’t have tenure, who are living in precarity as adjuncts, and who are trying their best to maintain what I think is – And this is my educator speak coming in – The optimistic ideals of what higher education in this country, in the western academy, can do for students. And standing up against administrators who are trying hard to maintain the status quo in this place where it’s all about knowledge production until it’s not right.

It’s all about this idealistic search for truth, for building spaces where communities can grow and learn and debate with one another until that debate cuts into an alumni salary. You know what I mean? And it’s very interesting to see how each individual has chosen to chart their path in maintaining that dissidence for the sheer fact that morally it’s the right thing to do.

Josh Fernandez: Yeah. Absolutely.

Mel Buer: Especially when you’re up against a juggernaut like a very well-funded administration, and ultimately for you, that investigation was unfounded. They put you through over a year of –

Josh Fernandez: It was over a year –

Mel Buer: – Interviews. And they came back and they said you weren’t doing what they said you were doing. How do you feel about that?

Josh Fernandez: – I don’t know how to feel about it. It was so weird. I was pissed because they were accusing me… I remember sitting in the human resources place and the human resources guy was like, well, what if you’re going to these protests and holding a knife over your head? And I’m like, what? And he’s like, well, what if you’re doing that? I’m like, I don’t know. What if you’re doing that? [Laughs] No one’s doing that. So those were the kinds of attacks that were being leveraged against me. It was weird. Halfway through the process, I turned it on myself and I’m like, what if I am doing these things? Am I doing these things?

If it’s consistent enough, you start questioning your values. So the fact that they got me to question myself, I was like, damn, this is really bad. This is horrible. Then when it came out like, oh, he wasn’t doing any of this stuff we were accusing him of, it left me with this empty feeling. I was like, these aren’t the people that I thought they were, and I’m probably not the person they thought I was, so what am I doing here? It ultimately came back to the students. I love teaching more than anything. I love it. I love being in the classroom, I love my students, I love being able to connect with people, and so that’s what I put my energy into. And right after that investigation, I became a rep with our union because I’m like, this is what I want to do. This is what I want to dedicate my time to, the students, and then also, keeping the management at bay.

Mel Buer: Yeah, I feel that. I have a special love for teaching. The pandemic made it difficult to maintain a teaching job. Who knows? Maybe in the future, we’ll get back to it.

Josh Fernandez: Yeah, definitely.

Mel Buer: I want to have a bit of a discussion about the feelings of rage and how that contributes to not-so-productive ways to push that rage out of yourself. I am also a former addict and alcoholic, and this is not something that I spent a whole lot of time talking publicly about. There are some podcast episodes from years ago on the Revolutionary Left Radio podcast where I have conversations about it.

Josh Fernandez: Well, here we go, Mel. It’s your time to shine.

Mel Buer: Let’s chat about it. There’s a huge piece of your personal development, your movement into adulthood, and coming from – And stop me if you don’t want to have too much of a conversation about this –

Josh Fernandez: I’m good. No, I’m down.

Mel Buer: – Coming from a pretty broken home, trying to patch it up with your parents, your mom getting remarried, having a lot of misplaced anger about things that as a child you didn’t quite understand, and how that leads you to this space of desperately trying anything to feel right-side up again when you’re in such chaos.

When I was in high school and the first couple of years of college, I did a lot of living in three or four years so that I would not visit upon my worst enemy. And a lot of it stemmed from the same feelings of not knowing who I was, not having a sense of who I could be, not having a supportive space at home to be able to try out those ideas, and feeling a lot of anger at the system, myself in it, higher education as I was participating in it, the people I was around, and that ultimately turned into near consistent staying fucked up all the time because it made sense to me.

I get the same sense from your memoir and I get the same sense from your travels. And it takes a while to extricate yourself from that space when you’re so young and you don’t have a whole lot of life experience. So the only thing you know is either chaos at home or chaos internally turned into drinking too much or whatever your drug of choice is. I’m fascinated by your journey to sobriety and the ways in which you found spaces to be able to channel hot boiling rage under the skin into something that feels far more productive; whether it’s the ultra running that you do or the self-defense work that you’re engaged in in queer and anti-fascist communities. How do you feel about that? What is the importance of that for you?

Josh Fernandez: Yeah. I grew up in a family that would tell me to suppress my rage and it wasn’t okay. And for so long I tried to do that, and like you were saying, it bubbles up in these destructive ways. But it turns out I’m just a rageful person; That’s part of who I am, is just pure rage. And I realized way later, like way after I was burning out on drugs and alcohol and all that, I can’t suppress it; I have to channel it. So that’s where running came in. Running really helped me. Even though when I started running, I was still smoking cigarettes and a complete drunk, I would run around the park drunk and be like, well, this is something [laughs].

It’s getting something out of my system; I don’t know what it is, I’m hungover while running. But there’s this part of me that wants to torture myself a little bit. Some people cut, some people do drugs, some people drink, and I’ve done all those things, but what I realized is there can be a good torture of yourself, and that’s where ultra running comes in for me. It’s like torture and it fucks up your body and it’s probably not good for you in the long run, but it’s better for you than other things could be. Sparring people, when you’re fighting in kickboxing, is probably not the greatest thing I could be doing because I get punched in the face a lot and kicked in the face and I get knocked…

But it’s more positive than other things I could be doing and it gets out so much rage. And in this context of a self-defense collective where we’re trying to cater to Black and Brown and queer people, it’s a positive thing. I’ve seen the positive effects on people, and I’ve seen people come in low or “I don’t know what I’m doing” and come out feeling exhilarated. And for me, that feeling of exhilaration can lead to something revolutionary, that feeling of exercise can lead to something revolutionary. And I feel like we’re onto something there because when people think of revolutionary, they don’t necessarily think of jock-type shit. They don’t think of athletics. So for me, I’ve found revolution in working out and stuff like that. I like that part about myself, and for so long I didn’t like anything about myself. So I think the key to living, for me at least, is to find the things that you like about yourself and exaggerate them and do them as much as you can.

Mel Buer: I appreciate that you spend a good chunk of the book talking about – To circle back around to this point about the masochism of a rage-filled individual – I like that you see these exercises and these experiences that you put your body through as being a way to explore the limits of your own human experience. It makes sense to me. When I was organizing full-time in Nebraska where I’m from, we spent a lot of time doing the same things. We had workout clubs, we did self-defense classes. These are a bunch of individuals, the young 20-somethings who are feeling helpless post-2016, feeling without a direction, and wanting to feel more empowered. I think that’s where the revolutionary aspect comes from. We’re talking about individuals, Black, Brown, queer folks, and other low working class individuals, who have always felt oppressed and put upon by individuals who have more money, more power, and who are like a runaway train.

It sucks to be rooted in place watching the world burn and not knowing what to do about it. Beyond community organizing, being able to grapple with the limits of your own physical space, and taking the time to feel that empowerment through hard work changed my perspective when I was still organizing with these folks, at the Nebraska Life Coalition in Omaha. It also gives you a chance to get to know the people around you and to feel more of a sense of community as you’re trying to further this revolutionary project. So, those are my thoughts. I think it’s great.

Josh Fernandez: It is. And I like what you said about the community aspect. It’s hard now to connect with people. It’s getting harder to connect with people. I was watching the commercial for the Apple goggles thingies, and now there are videos of people getting out of their Tesla truck with the Apple goggles and you don’t even need anyone anymore, and it’s easier and more fun to not need anyone. But that doesn’t work for what we’re trying to do to create a better world and create a more human world. So these activities, sparring with people, giving them hugs afterward, and sitting around while you’re all tired out, that’s a community to me. We need to get back to that kind of stuff.

Mel Buer: It dovetails nicely with the general idea. There are a lot of our listeners who maybe aren’t familiar with what anti-fascist or community organizing looks like on a more mutual aid level. A lot of my listeners are movement organizers who’ve been doing this for a long time, but a lot of my listeners are your run-of-the-mill, progressive, slightly older individuals who may have never experienced that before. So, when we’re talking about community defense, we’re talking about any fascist or any racist community defense. The first line is breaking down those barriers between individuals to be able to, at its base level, communicate effectively when there are threats that are presenting themselves to a particular group. Now, this could be a neighborhood, this could be a campus group, or this could be individuals at a community center; What that community looks like and its makeup is different in every location.

But the main thing is that oppressed minorities, individuals who do not have the same political power that your typical white male or white woman has, feel that threat and need to be able to effectively communicate that threat and neutralize that threat. Whether that’s through online organizing – Especially during the Trump era, we saw a lot of that organizing happening. It still does – Or through the community self-defense that you have engaged in now and in the past, in your area around Sacramento and elsewhere. I was wondering if you could speak to the anti-racist, anti-fascist organizing that you’ve done, and give our listeners more of an insight into what that looks like for you and the folks around your area.

Josh Fernandez: When I first started when I was a teenager, it was at punk shows and it was a direct confrontation. It was very crude and very unorganized, but still, there was a sense of organization. There was a group called Anti-Racist Action, and so much later during Trump’s presidency, a lot of that organizing was coming back. So I dug into my past to bring that into the modern era. A lot of people did that, but there were a lot of younger people organizing too, and they had different tactics. The research aspect was new to me so that was something that I was learning that was effective. It was cool to see all the old heads and the new, younger kids teaming up to idea-share and skill-share.

The research aspect of it is something that I enjoyed, it’s so effective, and it gets rid of the need for a lot of the crude aspects of ARA, like the violence and the direct confrontation, because it can cut it off. This relentless doxxing campaign against white nationalists, to me, it’s beautiful. I love it because it makes people think twice about what they’re doing and historically, it’s stopped a lot of people from organizing dead in their tracks. They don’t want to deal with it. They don’t want to deal with this relentless campaign of online harassment and the neighborhood harassment with flyers, their jobs are at risk, and it’s too much. It’s this pressure campaign that gets rid of the need for some of the violent confrontations that happen.

Mel Buer: That’s an important point because we’ve seen, and unfortunately, likely we’ll see, these violent confrontations often become deadly. White nationalists and white supremacists bring guns to rallies now and openly carry those guns. I know that there are contingents of anti-fascists who are also gun carriers in this country and will do what they need to defend themselves. But that’s a lot of unnecessary violence to court because Nazis don’t play fair. And a lot of idealistic anti-fascists may have not come up against that certain level of violence.

So being able to kneecap a movement without actually kneecapping a person, saves a lot of lives. It also potentially opens up avenues for these disaffected young people who find themselves drawn into fascist movements to give them a pathway out of it. And to help them take the distance they need to take in order to see that the ideology that they’ve been pulled into is not the way forward. Which is an interesting thought process that I’ve always thought about as being uniquely suited in the classroom; The classroom is an important place where that conversation can happen.

Also, when I was teaching, I was teaching at community colleges, I was teaching at the university where I got my master’s degree. It’s a generally liberal, progressive university. It’s a state school in Nebraska. And there’s always at least one student in every class who sees the conversation that you have – I was teaching writing classes as well, so it was argumentation. It was, let’s pick apart this op-ed and see what we can pull out of it in terms of the skillset that you’re trying to build as an academic writer. What can you learn from this? – And there’s always one student who thinks that you’re trying to push some liberal agenda and starts including reactionary topics in their submissions, which they think you’ll fail them because they’re talking about ultra-conservative, potentially borderline offensive things. And they’re trying to argue these things, similar to the student who blurted out that he wanted to talk about slavery and how Black people should forget slavery in the book, and you have to sit there and you have to break that down with them.

In higher education, there’s time in the classroom to be able to do that. Having that space to be able to use education and the educational setting, do you think that is effective in opening up that space for self-reflection for that reactionary ideology that some young gravitate towards?

Josh Fernandez: Absolutely. I teach at a special place because it’s a white, well-to-do community college, and that’s the majority of my students. A lot of my early papers in my composition classes are like, there’s only two genders, and that’s the thesis. And you can almost see them look at me like, what are you going to say? They don’t understand that I don’t care about that. We’re going to talk about it and we’re going to critically think our way out of that, but I’m not going to preach to them. I’m not going to fail them, I’m not going to preach to them, and they think I’m a liberal and I’m not. I’m an anarchist, I think differently, and I’m not a reactionary like that. I like humans, even humans I disagree with and who are wrong, I’m not going to use my power against them.

So that’s part of my principle as a teacher, is I don’t use my power against you. I know I have it but I’m going to do everything I can to not use that. We’re going to talk like humans and we’re going to figure things out. And my students appreciate that. I never talk about anti-fascism, I never talk even about anti-racism in my classes for the simple fact that I know that some of them will turn away from me and that’s not what I want. So I just go in there as a writing teacher and I teach them how to write. Almost all the time my students want to stay in contact with me because they’re like, oh, you’re not like the other professors. You’re nice and you care about us, and then they’ll start –

Mel Buer: What a low bar. I’m sorry.

Josh Fernandez: – It’s such a low bar, right? I know. That’s such a good comment. It’s such a low bar, it’s so easy. I’m like, this is what makes me a good teacher? Respecting you as a human being? They started showing up at my readings and stuff, and they started caring about the things I do and the things I think, and they started asking me about my tattoos and they’re like, oh, wow. I didn’t really –

I remember at my last reading, one of my students who considers himself a far-right conservative, showed up and after my reading, he’s like, that was good. So it was me, him, and then one of my leftist trans students, all of us standing in the parking lot after my reading, under the moon, talking about life, and I had just given this reading about beating the shit out of neo-Nazis. All three of us were on the same level, we were talking about how hard life is, and our struggles. That’s how it happens. It’s not the liberal going into class, making them read some bullshit, and then telling them what to think because this is the right way to think. It’s not that, it’s treating people as if they are humans, which is such a low bar and it’s so easy.

Mel Buer: It’s also interesting too, you’re bringing this into the prison system and you’re teaching some folks who are some brutal individuals, who have led some brutal lives, who have done some brutal things, and you’re bringing that philosophy into prison classrooms. What has that experience been like? As I have gathered, you are an abolitionist and absolutely one who has spent a lot of time kicking the shit out of Nazis, and you are also teaching some of them in prison. There is this sense of real humanity that you are introducing into this classroom that I admire. Can you talk about the work that you do in the prison system and what that has been like these last couple of years?

Josh Fernandez: It’s been great. I’ve been at the prison since… 2018 is when I started. Just yesterday, one of my students who wrote his first paper about being in the American Nazi Party, was sitting up front in my class holding my book, and he was proud of his professor. American Nazi Party with a book cover of me shirtless with a bat that says, “Fuck Nazis,” on it. I wish I could bring a camera in there because it was like he’s very obviously a neo-Nazi. But holding my book would be the best picture ever. So the same thing I do out here, I try to bring that thing into the prison. I want to bring humanity into the prison because their bodies are controlled, everything about their lives is controlled, and I want them to see my class as a place where we can just be humans with each other and not have to fall victim to the same thing that the guards put them through.

My class is a sanctuary and I want everyone to see that; no matter if they have these brutal ideologies that I disagree with. Once they see me treating them like a human, our class opens up to everything and then we start talking about our ideologies. And even the neo-Nazis will talk about their ideologies in terms of, it doesn’t quite make sense, but I’m in this and I grew up in this prison and this is just the path I’ve chosen. So we start breaking down ideologies and what they mean and why they’re there. It’s really interesting. It’s the best part of my job, I love it. It’s really hard and it’s really sad going through the process and the guards treat me like I’m one of the inmates basically, but it’s worth it. It’s all worth it, I love it.

Mel Buer: A great way to close out this conversation would be to talk about your philosophy around writing and what writing can do for an individual because I think we share some ideas about it and what the writing process can do for someone. The thing that will probably send me back into the classroom, because I miss teaching, are the moments when my students walk into the class going, I don’t want to be here. I don’t know how to write. I don’t care about writing. I don’t know why I need to be here. I just need it for gen ed. I want to get done and move on. And the whole process of writing intimidates many, many people. They’re like, well, I could do math, but I sucked at English in high school.

It’s this concept of students and anyone who doesn’t spend time writing doesn’t know that very quickly you can sort of unlock these possibilities about the process of self-discovery, how to read yourself and others, and what the written language does to help us make sense of the world around us. It’s a beautiful moment, probably three or four weeks in the class of regular writing exercises about whatever the hell folks want to write about, that students start to understand that like, oh, I can do this. The light bulb goes off. We get past that initial problem.

I love the analogy that you used for students who were staring at a blank cursor on a page; Filling up these rooms in your house and imagining what your childhood home looks like and how you can fill up that space with each paragraph. Being able to see that comprehension click into place, it slides in and then students suddenly feel like, okay, now that I can fill up a page let’s build the skillset that allows you to be successful in an academic setting and ultimately in a job setting. I love that process and it’s been lovely to also have students email me a couple of years later to say your feedback gave me the confidence to pursue this seriously as a career. And my thought, my first answer is, I’m so sorry. Welcome to hell.

Josh Fernandez: Totally, yeah.

Mel Buer: The job market sucks but also I’m so glad that you have found this space to be creative. You’ve found the space to be able to make sense of who you are and the thoughts that are rolling past your face every day. Welcome. What are your thoughts about that? The writing process and how you’ve translated that to your students?

Josh Fernandez: First of all, you need to get back in the classroom, Mel. You’ve got to get back. We need you. We need you in there.

Mel Buer: We’ll see. We’ll see.

Josh Fernandez: Yeah. That’s what it is. I prefer the students who are like, I hate writing. I can’t do it. Because those are the students who have nothing to lose. They’re just like, I don’t know shit about this. So I’m like, I can work with that. The students that scare me are the ones who are like, oh, yeah, I’m a writer. I know everything. Because they’re already on their path and you can’t tell them anything. But yeah, the students who are afraid of it, who are like, I don’t understand how to do it. It’s crazy to me, I’m not creative. I’m not this, I’m not that. I have no story to tell.

Mel Buer: Total lie every time.

Josh Fernandez: Total lie. That’s the thing, once people understand that their life is fascinating to people on the outside, no matter what they’ve done or haven’t done, their lives are fascinating. And I am a nosy ass person who wants to understand everybody’s life. I just want to know everyone’s life and there are a lot of people like that. So, my students who are locked up especially, they’re like, oh, no, everything’s boring. I don’t know what the hell I’d write about. I’m like, are you serious? There are so many people outside who would love to understand your story. And once you can get that through their heads, something unlocks and they’re excited about writing. That idea of unlocking something that was always there, it’s in everyone. Everyone can write and everyone wants to be heard. Everyone wants to tell a story of some kind but to unlock that little door that’s inside of them is special.

Mel Buer: It is. And it helps break the monotony of higher education and the machinery that we force these young people through in order to try and get a piece of very, very diminishing returns on the other end of what higher education is supposed to offer students in terms of job security or any life security. The university is a brutalist machine and it’s churning students out, human bodies, and workers out. And every once in a while, you get caught up in it and it’s nice to be able to set up… This is why – And this is a whole separate conversation – The humanities exist in the university for a reason and being able to tap into the legacy of the culture that you are a part of in the Western world without becoming a chauvinist is important. We come from somewhere. We’re going somewhere. We exist in this place. This is my idealism, but it’s not all about gathering skills in order to be a good worker.

It’s about making sense of who you are. And the humanities are the place to do that and literature is the place to do that. And being able to translate that into writing is important. I love my students who are like, I’m boring. It’s like, really though? You think your life is interesting, why wouldn’t someone else think that your life is interesting?”

Josh Fernandez: Yeah, absolutely.

Mel Buer: Let’s give you the tools to be able to accurately tell the story, to tell the story in such a way that invites people into the infinite universe that is your personhood, and grounds you in that space of humanity. Because everything in this fucking system, everything about capitalism is designed to blunt the edges of who you are and make it impossible for someone to know you. So make use of this. Then if you leave this class and you never want to write again and you’re done and you want to write your papers on business administration or whatever the fuck you want to do, that’s fine. You’ll remember this class in 50 years when you want to write a memoir because it always happens. You want someone to know about your life.

Josh Fernandez: It’s true. Yeah, it’s true. I’ve been teaching long enough to where students have contacted me 10 years later and they’re like, something clicked in me. Seven years after I took your class, something clicked. I’m like, oh, I get it. That’s fine too, I think that’s great. They’re making twice as much as I do now in their new job. They’re like, I want to be a writer now.

Mel Buer: Yeah, it’s great. It’s good. Welcome. The more the merrier.

Josh Fernandez: Right.

Mel Buer: But yeah, any final thoughts about the memoir or this conversation? Where can folks find your work? Where can they find your book? Anything else before we close out the chat?

Josh Fernandez: Yeah. Thanks, PM Press. The book is out on PM Press, which has a ton of great titles, as I’m sure you know. Working with them has been amazing, seriously, the best experience I’ve ever had with a publisher. Amazing people. You never know. You see PM Press and then you’re like, who knows what goes on over there? But they contacted me to buy the manuscript and they have been the coolest people. I’m all about human connection and conversation and they’ve been so communicative and cool this whole process. So I don’t know if anyone’s listening to this and wants to publish but PM is a great place. It’s a great place full of amazing people who are doing cool work. So there’s that. That’s my company man pitch. But otherwise, yeah, you can get my book on PM Press and it comes out February 13.

Mel Buer: I’m so excited for folks to read this. This was such a joy. I picked it up and put it down in a day. I read this in a day.

Josh Fernandez: Nice. I love it. I love it.

Mel Buer: And it is a great cover. I love that. The Hands that Crafted the Bomb: The Making of a Lifelong Antifascist by Josh Fernandez is out at PM Press on February 13. This episode is coming out next Thursday, so it will be out. Get your book, folks. It’s really good and it’s worth a read. Thank you so much for coming on and thanks for a great conversation about things that I love to talk about. I appreciate it and I hope you have a good morning.

Josh Fernandez: Thanks, Mel.

Mel Buer: That’s it for us here at The Real News Network Podcast. Once again, I’m your host, Mel Buer. If you love today’s episode, be sure to subscribe to the podcast to get notified when the next one drops. You can find us on most platforms including Spotify and YouTube. If you’re listening to us on YouTube, don’t forget to leave us a comment, like, subscribe to the channel, and set your notifications for the next time a new episode drops.

If you’d like to get in touch with me, you can find me on most social media, my DMs are always open. Or send me a message via email at [email protected]. Send your tips, comments, questions, episode ideas, gripes, concerns, or anything else you’d like to send me. I’d love to hear from you. Thank you so much for sticking around and I’ll see you next time.