Void Network

January 25th, 2024

Over the last couple of decades an ideological battle has raged over the political legacy and cultural symbolism of the “golden age” pirates who roamed the seas between the Caribbean Islands and the Indian Ocean from 1690 to 1725. They are depicted as romanticized villains on the one hand, and as genuine social rebels on the other. Life Under the Jolly Roger by Gabriel Kuhn examines the political and cultural significance of these nomadic outlaws by relating historical accounts to a wide range of theoretical concepts–reaching from Marshall Sahlins and Pierre Clastres to Mao-Tse Tung and Eric J. Hobsbawm via Friedrich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault. The meanings of race, gender, sexuality and disability in golden age pirate communities are analyzed and contextualized, as are the pirates’ forms of organization, economy and ethics.

While providing an extensive catalog of scholarly references for the academic reader, this delightful and engaging study is directed at a wide audience and demands no other requirements than a love for pirates, daring theoretical speculation and passionate, yet respectful, inquiry.

Gabriel Kuhn (born in Innsbruck, Austria, 1972) lives as an independent author and translator in Stockholm, Sweden. His publications in German include the award-winning ‘Neuer Anarchismus’ in den USA: Seattle und die Folgen (2008). His publications with PM Press include Life Under the Jolly Roger: Reflections on Golden Age Piracy (2010), Sober Living for the Revolution: Hardcore Punk, Straight Edge, and Radical Politics (2010), Soccer vs. the State: Tackling Football and Radical Politics (2011), Turning Money into Revolution: The Unlikely Story of Denmark’s Revolutionary Bank Robbers (2014), and Liberating Sápmi: Indigenous Resistance in Europe’s Far North (2020). He blogs at lefttwothree.org.

Tasos Sagris, co-founder of Void Network and the Institute for Experimental Arts is a poet, theatre director and cultural activist from Athens. His publications in English include We Are an Image From the Future The Greek Revolt of December 2008 (AK Press, 2010) and From Democracy to Freedom (Crimethinc, 2016).

1.

T.S.: The bourgeoisie created their own universities, academies, honored scientists and publication companies to praise their own establishment as the only possible way of existence, defend private property and the dominant regime, to honor the myths, the history and the superior glory of the upper class, to delegitimize the efforts of the oppressed for social liberation. A characteristic that I love in your books is your uncompromised dedication to consciously write history books for the benefit of the global anarchist movement. What is the role of the anarchist scientists in our struggle against domination?

G.K.: The production of knowledge isnothing neutral. We select material and interpret it based and on how we view the world (our “epistemology,” as people who like those kinds of word would say) as well as on our moral, social, and cultural norms. There is nothing objective about allegedly objective science.

I don’t think this means that there’s a free-for-all type of scholarship, where you simply make up stories and sell them as historical truth. That’s not scholarship, that’s manipulation. Certain things happened in certain ways, and we have a responsibility to acknowledge that. But we also have a responsibility to acknowledge why and how we tell certain stories. We can watch the same football game and, without either of us lying, tell two very different stories about it. The more that the audience knows about us and our interests, the easier it will be for them to interpret our stories and make up their own mind about what happened.

So, this is how I see anarchist scholarship. I am interested in people fighting for freedom and justice. These are the stories I will seek out, and I will look at everything from that angle. There is no point in manipulating the facts. We don’t win by doing that just so that the story fits our interests in the best possible way. People will realize what we’re doing, and we’ll lose credibility. But we can refuse to buy into a way of writing history where the powerful always get their way, where everything supposedly happened in their favor because it was just, deserved, and inevitable. Anarchist scholarship means to say, no, there have always been power struggles, there have always been subversive movements, and these movements haven’t always losteither and they might indeedwin more often in the future if we learn our lessons right.

2.

T.S.: What inspired you to write a book about the pirates?

G.K.: Originally, a fascination with pirate life that I believe a lot of teenagers share. Freedom, courage, adventure! Once I learned that there was more to that than simple imagination, that pirate communities actually were quite progressive and democratic for their time, I added some research to the fascination and wrote a little book about pirates as a student in Austria. It was translated into English, and based on that translation PM Press asked me some years later do to an updated and expanded version of it. That’s how Life Under the Jolly Roger came about.

3.

T.S.: William Burroughs in his wonderful, utopian book Cities of the Red Night, builds a fictional argument that the possible success of the piratic struggles against the established powers of their era could activate revolutionary conditions in the mainland of Europe much earlier and much more progressive than French revolution. What you think about the Burroughs argument and why this didn’t happen? What was the influence of the piratic actions in the other side of the planet to the masses of poor people of Europe in 16th-17th century?

G.K.: As you say, Burrough’saccount is a work of fiction, and he uses the example of a pirate community in Madagascar by the name of Libertaliaas a kind of radical utopia. Libertalia was described in Captain Johnson’s famous History of the Pirates from 1724. Burroughs is not the only one who has incorporated Libertalia in his writing. It probably never existed, butit inspires radical utopias to this day.

Personally, I think that if you read Captain Johnson’s book closely, Libertalia is not that great of a model, it’s more like an outpost of European republicanism in Africa, but that’s a separate discussion. That Captain Johnson would write about it all goes to show that, already in the early eighteenth century, people used pirate communities to project progressive ideas onto them. Burrough’s argument is a little like wishful thinking: “Had the pirates at the time been as radical and powerful as I would have wanted them to be, they could have radicalized mainland Europe.” But there probably was no Libertalia, and the overall power of the pirates was limited.

However, there were clear connections between radical political movements in the seventeenth century and the so-called golden age of piracy, which started in the Caribbean around 1680. The British had exiled many radicals from the English Revolution to the Caribbean colonies, and not few of them ended up in the ranks of the pirates. How inspirational the pirates were on the poor masses of Europe is hard to say, but the fact that pirate plays were staged at popular English theaters already in the late seventeenth century would indicate that they had some impact. So, there was a synergetic effect between radicals on the European mainland and pirate communities.

Had this led to broad social movements able to advance radical political change, Burrough’s fantasy maybe could have become a reality. Pirate communities were certainly more radical than the bourgeois fellows who staged the French Revolution. But they weren’t strong and influential enough. The nation-states were able to crush them. Too bad.

4.

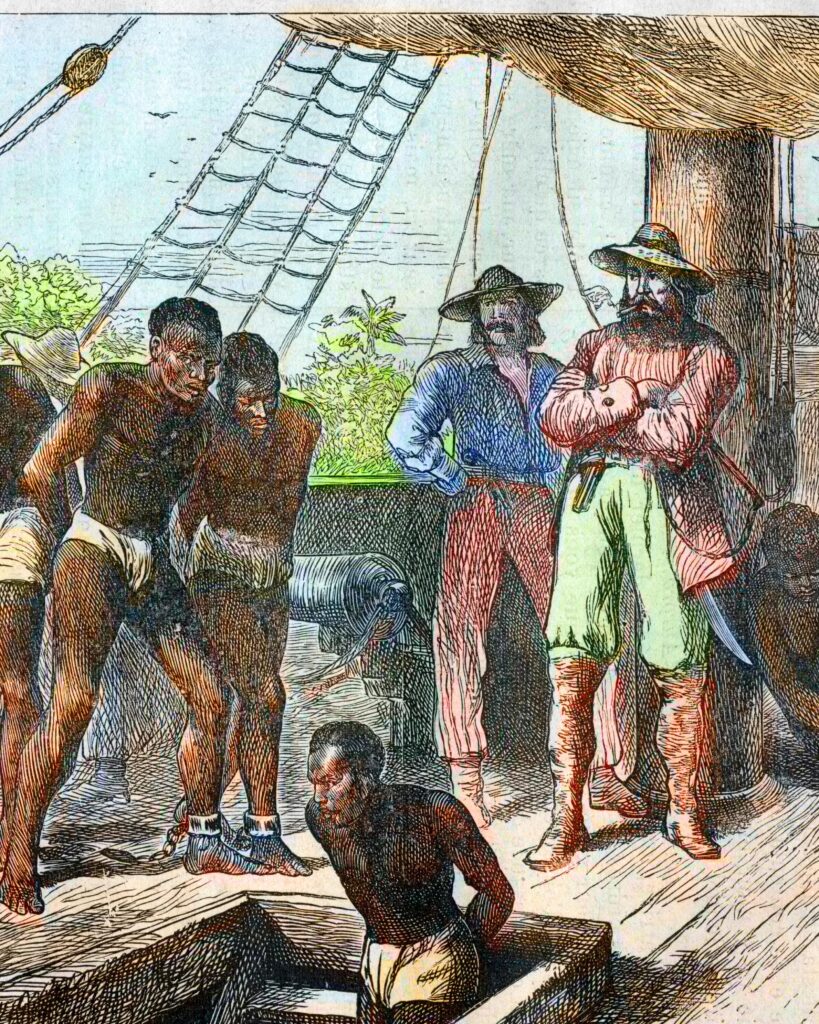

T.S.: Your book offers us amazing parts of criticism to the pirates. As you mention most of them was Dutch, French and English racists, slave hunters and looters of poor villages. How could this stop the first wave of capital accumulation? Were pirates revolutionaries and what exactly was revolutionary among their practices?

G.K.: There might have been elements of conscious revolutionary activities among the pirates – as I said, people with political experience were in their ranks – but I believe it was minor. I don’t think there was much of an explicit critique of early capitalism. Yet, while pirates understood that in a capitalist society you needed material wealth to lead a good life, they weren’t willing to subject themselves to the life that capitalism had foreseen for them: toiling away for a few crumbs of the cake, under the whip of both bosses, politicians, and security forces. By raiding merchant ships and coastal towns, they disrupted early capitalist trade to the point of threatening capital’s global expansion. Perhaps that turned them into some kind of proxy revolutionaries who didn’t care much about thelabel themselves. But they became the nation-states’ enemy number one during those years. There have always been plenty of criminals, but not all of them threatened the economic and political order by taking from it whilerejecting its foundations.

5.

T.S.: In your book you offer us a historical analysis of the Pirate’s legacy from a revolutionary perspective. There are a lot of horrible choices, mistakes and a lot of failures in the piratic history – but, there is an emancipatory and revolutionary element to the life and struggle of the Piratic communities.

A.

T.S.: Can we learn something useful for our social struggles from the pirates of the past?

G.K.: Considering that the pirates haven’t left us with any records or writings, it’s perhaps hard to “learn” much in any more classical sense, but, like few others in European history, the pirates indicate the starting point of any radical transformation: to reject the status quo, to refuse to play by the rules, and to try to live a different life at the risk of being killed for it. This is where revolutionary change begins, and the pirates tick those boxes. And I believe that’s where their main role lies even for radical movements today. They are inspirators.

B.

T.S.: Probably one of the finest characteristics of your book is that you offer us detailed informations about the failures and mistakes of the pirates. What you think the pirates did and we have to avoid in our plans for social liberation?

G.K: I think the biggest problem was that pirate society wasn’t sustainable. To begin with, there were, essentially, no women, so the society couldn’t reproduce itself. To maintain its numbers, it constantly needed new people to join. There was a high turnover, and not everyone coming in necessarily espoused the same ideals or interpreted the pirate way in the same manner. During the final years of the golden age, when the pirates fought for their survival, they would force people to join their ships just to keep up the numbers. Obviously, this can’t work in the long run.

There were also no binding social structures that could have facilitated the survival of pirate society. I don’t think institutions were needed, not even necessarily organizations. But some common features beyond the pirate flag that held everything together. Look at hardcore punk: it’s been around for almost half a century, lacks institutions and organizations, but it has a number of common features: the music, an anti-establishment attitude, DIY values, venues where people regularly gather, zines (or today perhaps blogs) that serve as common reference points. Any community, any movement needs some kind of social glue. I think that glue was missing among the pirates.

Other than that, I believe there wasn’t much that the pirates “did wrong.” There were internal contradictions, but any society has internal contradictions. These contradictions can be worked out: sometimes, they’re even healthy. At the end of the day, the pirates suffered a simple fate: they were militarily crushed by their enemy. Many radical movements suffered the same fate.

C

T.S.: Do you believe that the anarchist movements of today have some kind of connection with these crazy motherfuckers, 300 years after their defeat from the kings, and queens and proto-capitalists? Is there something that connects anarchists with the pirates and into what they can benefit the future revolutions? What you think the pirates can offer as reference points to the revolutionaries of our generation? Are these images of a vision for the future?

G.K.: Yes, I think there’s a connection through the rebellious spirit that the radicals of today and tomorrow share with the pirates. That spirit can benefit any revolutionary movement. The pirates provide a vision for the future insofar as they tried to create their own communities apart from the state. That’s animportant aspect of the pirates and their power of inspiration: their communities were set apart from the system in very tangible ways; they were out there on their ships, somewhere on an ocean much harder to scale and monitor than today, able to hide on faraway islands, in lagoons and mazelike river deltas. How can this not be inspirational?

6.

T.S.: A very unique and interesting process in your book is that you put the Piratic communities under very detailed investigation based on the strategic thought of different revolutionary thinkers. Among them we found chapters based on revolutionary strategies of MaoTse Tung, Carlos Marighella, the social bandits theory of Eric Hobsbawm, war machine and nomadism of Deleuze andGuattari, ecstatic life of Nietzsche. What lead you to apply this method and what was the result of this experiment?

This really came out of the studies I did at the time I started writing about pirates. I was a philosophy student and I liked theory and the history of ideas. I have close to zero interest in academic philosophy today and no longer read much of the kind of literature I read back then. I pretty much stick to history and concrete political debate. With that said, ideas are nice. In What Is Philosophy?, Deleuze and Guattari write that philosophy is about creating concepts. I like that. Theory can easily turn into nonsensical blah blah, especially when academic bubbles detached from everyday life need a justification to reproduce privileged social spaces, but without theory, without developing concepts based on everyday experience that can be used to alter that experience, there is no social progress. The intention with the pirate book was to do something in that vein: to use theory, but to use it in a very practical manner, to flesh out concepts that, in turn, can inspire action. How well that worked is up to the readers to decide. I will say, though, that one of the nicest compliments I got for the book was an accomplished fiction writer saying that it was the first time Deleuze and Guattari made any sense to them.

7.

The disrespect to private property, the break of social constraints and the need for communal solving of the social and private problems caused by inequality and exploitation seem that brings the pirates close to any one of lower class people. Why you think 500 years after the death of the pirates we are still fighting the upper class without obvious success of overthrowing them?

Thanks for an easy question!

Seriously, I don’t know. But let’s try to look at it from an angle where the pirates might be able to help. German anarchist Gustav Landauer was fascinated by a small, sixteenth-century book authored by the French humanist Étienne de la Boétie. It is known in English as the Discourse on Voluntary Servitude. Why, de la Boétie asked, do people so often choose to support social structures that obviously aren’t beneficial to their well-being? The theme has reappeared in radical writing throughout the centuries, not least after the horrific experience of twentieth-century fascism. If anyone had found an answer to the problem yet, we would probably live in a very different world, but: the pirates, clearly, weren’t voluntary servants. They broke with a pattern that is essential for oppressive power structures to work. It’s a key lesson to learn from them.

8.

T.S.: The only images I have before your book about the pirates comes from Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, the Pirate Utopias by Hakim Bey and the amazing TV series Black Sails. In all of them it seems that the pirates join forces under specific circumstances, only if they are under serious threat and without any specific prearranged plan or general strategy. Most of the other time they fight each other, they don’t communicate or trust each other and they are not capable to have any general plan. This reminds me a lot the anarchist and leftist groups today all around the world. What was the reason that the pirates (and still ourselves) fail to find organizing methods that will make use of our differences and disagreements as a beneficial weapon against our common enemies and not as a way of self-destruction and disempowerment of our communities.

With respect to our scenes, I would say there are two main aspects. Both might seem trivial, but that doesn’t make them less relevant.

One is egoism. The great revolutionary theorists were right when they demanded a “new human being” as a precondition for revolutionary change. Now, a new human being doesn’t fall from the sky and can’t be created in some school or guerrilla training camp. It can’t precede the revolutionary struggle, it has to develop within it. But its development must be a main feature of the struggle, otherwise in-fighting will be inevitable. Even if we genuinely long for a society of equals, we have been socialized in a highly competitive, bourgeois environment, and this impacts our movements. We – even anarchists, if we are honest – will often want to lead, will want our ideas to be recognized as superior to others, will want to be acknowledged as the most revolutionary of all revolutionaries. Look at the entirely insignificant things that people can get worked up about. There is no explanation other than this being about ego trips that have nothing to do with the good of the people. We need to be wary of that and call it when we see it.

The other aspect was once summed up by the ever observant Ian MacKaye in the following manner: “People’s power is limited to their scope, and it’s like that saying goes: ‘The people who get hit are the people within arm’s reach.’” In short, if you can’t get to the real enemy – the politicians, the CEOs, the cops – you will let loose on the person next to you. You’ll want to get your anger and frustration out and feel like you’re getting somewhere, have a tiny victory, perhapspreventing their article from being published or excluding them from organizing the local anarchist bookfair. Psychologically, that’s understandable, but it’s devastating for our movements.

With respect to the pirates, I think it was even simpler, plain survival instinct. We have enough evidence to conclude that there was a genuine attempt on many pirate ships to create a rather democratic community with a relatively fair share of the wealth. This was stated in the “Codes” of the pirate ships that we have heard about a lot. But, as stated before, there was no strong social glue that guaranteed that you could expect the same on any pirate ship you signed on to, or that everyone signing the Codes really could be trusted.

I was also talking before about being socialized in a competitive society. Imagine the society that the pirates were socialized in. There was no “social peace” brought on by social-democratic class compromise. You had to struggle for your survival every day. Of course, this impacted the pirates. People were suspicious, also of one another. Again, too little social glue.

9.

In the introduction of your book you quote from Outcasts of the Sea: Pirates and Piracy, an Edward Lucie Smith’s book. The paragraph explains the popularity of piratic stories from 17th century until our days and the way the myths still influence our modern lives:

“The story of the pirates is a product of the urban imagination. One of its most important functions is to provide a safety valve against the pressures exerted on the individual by the demands of civic morality. The basic fantasies are those of unbridled freedom and power as compensation for what the average bourgeois is never going to achieve, however successful he may be on a material level.”

Is this a possible strategy for the anarchist movement of our era, producing such extraordinary actions and lifestyles that will appear as a myth in the miserable minds of the people around us? Can you share some ideas about what can be a myth like this today?

Yes, I never thought of it that way, but I suppose anarchism – at least a particular kind of anarchism – could do that. In simple terms, create ways of life that are attractive to people. They would entail a sense of adventure, make life exciting, but not on a purely individual level, there’d have to be an element of social justice. A Robin Hood-type element. “Social bandits” can do that, free-roaming travelers can do that, communes beyond the restrictions of bourgeois life can do that. In and of themselves, none of these projects are sufficient to bring about an anarchist society, but they contain important aspects of them and might make people curious about anarchism. Key, of course, is that these projects are not driven by people trying to demonstrate how much better they are than the masses (who “don’t get it”), essentially preventing any inspirational potential, but by people able to respond positively to curious inquiry, even by people who aren’t well-versed radicals and who don’t talk or look that way.

Anarchist ideas are attractive to people. Pretty much anyone likes freedom, and most people like justice, too. It’s just that few of them have seen examples of anarchist life that appear attractive. Partly, that’s the enemy’s fault who has done a good job to ensure that very few such examples exist. But partly it’s also our own fault because we haven’t been able to establish many, and easily get sidetracked by the problems mentioned above: in-fighting, showing off, etc.

The pirate flag still has power for a reason. It’s up to us to provide the right content.