The Break Up Theory

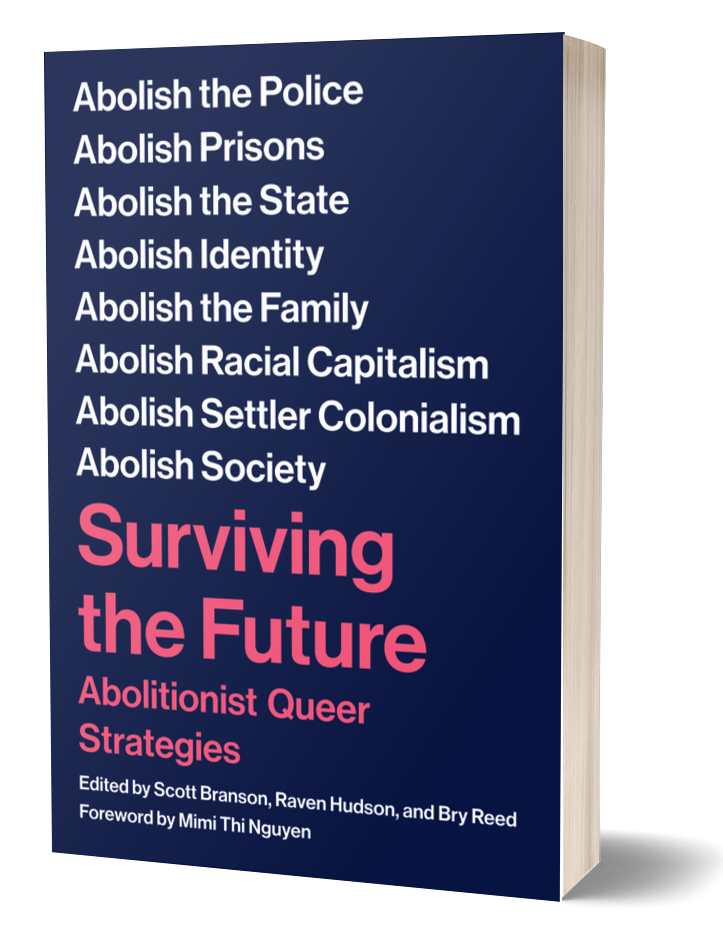

by Shuli Branson, editor of Surviving the Future

December 13th, 2023

Whatever you do, don’t break the social peace.

*

All they want is to keep the peace.

*

We can’t collude in maintaining social order.

*

In my previous essay, I framed my Jewish anti-Zionism as an anti-statism that extends to all states, even as Israel demonstrates explicitly the potential deathworld that every state contains. As I stated there, my position is anti-political, in that we shouldn’t reach for political solutions to the problems caused by the state and capital. In fact, I see the temptation into politics as a form on enclosure on our rebellion, a way to deflate and recuperate our movements. It’s a temptation that even seasoned anarchists are susceptible to, especially in times of desperation, because the normalized and accepted modes of changing our social conditions—politics—have such a hold on our imaginations.

However, political action mistakes where our real power lies, which is in the ways we reproduce the world—or more precisely when we refuse to do that. When we are on their turf, they will win. But if we don’t keep the social peace, we will see how much they fear us. Anti-politics is one way of understanding anarchism’s approach to liberation, to pull it away from the temptation of mass-based/worker’s movements, which have mostly been dominated by Marxisms (including a long historical erasure of anarchism, though for a long time anarchists lived in alternative social structures). This essay will explore some of my current despair in the anti-war movement arising against Israel’s genocide in Gaza, specifically thinking through the dead end of protest and our capitulation to these grammars of resistance. I don’t have any certain or cure-all solutions, though. To break the social peace will require multiple imaginaries of disorder and worldbuilding.

*

The day I started writing this, students at one of the universities where I teach blocked the entrance to two main buildings to disrupt normal operations of the school and to educate people on Palestine. I saw the police begin to swarm, and within an hour, I received an email from the school explaining that the university supports peaceful demonstration, but within the correct code of conduct, which doesn’t impede the functioning of the school, as long as it is peaceful. And so, these students, who did not adhere to the code, and did not get their protest okayed and didn’t hold it at the right time, would be subject to a “restorative” process of sanctions.

Despite the institutional jargon that a university with radical chic uses to gesture towards a tie to movements for liberation and justice, the clear message is: these students broke the rules and they would suffer consequences. The major rule about protesting—which they totally condone by the way—is that it doesn’t disrupt the normal operations of the school. This email simultaneously praising and condemning the students puts into focus the way that protest and demonstrations work in our culture: there is a certain acceptable language that everyone is quick to condone, particularly as an exercise of the unquestioned “right” to “free speech.” And there’s also an acknowledgment that protest, as a speech act, aims to call attention to an issue by somehow disrupting “business as usual” or the “normal operation of things.” But that disruption must occur within reasonable limits.

The tension of acceptable protest is between this righteous speaking out and real disruption. The grammar itself gives us a sense of doing things, even if the words we say are empty. (The slogans are always so bad!) The level of institutional tolerance allows for some disruption, but not too much . . . Enough disruption to say the people governing listened, or that you stood on the lines and chanted. Not enough to stop us from getting back to work.

*

The moment comes when the police tell you to disperse. The will doesn’t seem to be there to tip into a riot (sometimes it just takes one bold move). Now people either orderly leave, or submit themselves willingly to symbolic arrest.

If the police aren’t using their IDF training to subdue us, then we may as well just be making social media posts.

*

We need to look at all the actions we take every day that help to keep the social peace. When our actions still participate in political rhetoric, they can be swallowed up in their governance. To disrupt business as usual through the spectacle of protest actually contributes to business as usual. Particularly these days, there is a certain amount of respectable dissent that can counter any decision. And in the end, no matter what power US politicians have to end the genocidal assault on Gaza, they should fear for their own ability to govern, the revolt should be generalized. Palestine won’t be free with politicians governing here, there, or anywhere. It’s their systems that allow continual genocide and lock us in these useless patterns.

In other words, war and protest, mass death and righteous indignation. This is all business as usual.

We can make an analogy with parents asking for their children’s obedience. If the state and capital continually wage social war against us, forcing us to rely on them for existence, forcing us to work and live within their bounds, one of the major ways they do this is through norms of behavior. The harsh glance of a parent to a kid acting up. This is what keeps people silent at work when their coworkers are treated badly. It’s even what keeps us silent when our friends are harassed and hurt by other so-called friends. It’s what keeps abusers safe within communities who don’t want to risk disruption. It’s what makes kids go to bed on time. The things that can’t be said or done, bad manners, shocking behavior, risking gossip, being told you are crazy.

No matter how hard we chant, or how many of us there are, nothing we are doing compels change. And still we only envision change on their terms: stop doing the bad thing. We keep witnessing some of the largest demonstrations around the world (still paling in comparison the heroic resistance of Gazans amid their horrific martyrdom) and the politicians with whom we are investing the power to stop this war, or to at the very least tospeak against it, refuse to do a single thing.

Should we be fighting the police the way Palestinians resist the IDF?

I think it’s incumbent on Jews in any place to declare themselves against Israel and this ongoing genocide. I don’t think that is a sufficient action, but it’s a start. And for that reason, I think some good has come from Jewish Voice for Peace and other Jewish nonprofits leading spectacular protests where Jews visibly condemn Israel, who claims to act in our name and for our safety. I also appreciate a diversity of tactics, meaning mostly that I don’t want to sit and criticize people for trying out different actions to get the results they want. All success of liberatory movements—and success is a questionable term as long as this world persists—has come from a mix of action, with revolutionary violence as an ongoing threat. So many of us are desperate to feel like we have some power and consequence in this situation, and that also means showing up for protests that we know won’t get results, but that allow us to find each other. But the vocabulary of protest swallows our movements, wears us down, gives power to the managers of dissent. We should not speak their language.

The funding of the non-profits is enticing. It allows people to reduce their risk in involvement, even when they risk or encounter arrest. But it’s telling to me that most of the people at these big demos get minimal charges compared with Stop Cop City defendants or the J20 defendants from 2017. Everything lately has gone into making us forget that the George Floyd Rebellion took place, and the non-profit led protest movement right now is playing part of that role. With the recent civil disobedience actions, the orgs pay for people’s travel and court costs. This format streamlines the production of protest spectacle, makes the decision-making easier for those who want to feel like they are doing something—and ultimately it just counts us all as bodies for their actions. (As usual, anarchists will volunteer for these positions, as we tend to round out street movements, no matter how liberal they seem. We show up and know how to throw down.)

*

Spectacular protest, civil disobedience with planned arrest, “peaceful” marches that may as well be permitted, even if they are not—do these demonstrations of dissent against genocide provide any pressure or incentive for those in power to change course?

Dissent against genocide! What a ridiculous phrase anyway!

Pulling on tradition from the civil rights protests of the 1960s to ACT UP in the 1980s and 1990s, these demos fit fully within a commonly accepted vocabulary of protest, even when they do disrupt “business as usual,” like shutting down Grand Central Station or the Capitol Rotunda. Sure, these actions have some value, most notably in articulating a vocal Jewish anti-zionist voice of dissent, and increasing the visibility of Palestinian solidarity worldwide. But we might ask what could make these actions effective, and whether we even want the kind of effect they might produce. From the history of movements, like Black liberation in the 1960s, we know that reforms were won not by civil disobedience alone, but a context of armed self-defense and rioting. Their success also depended on media representation and reception. The mainstream media is concertedly ignoring this, maintaining status quo in support of Israel, despite massive protests. There is a version of reception to the spectacle of protest on corporate social media platforms, but all that does is offset the genocide being beamed into our palms daily.

In the West, larger disruption through armed resistance is not happening. There is seemingly no willingness to burn down their cities over this latest series of atrocities. We are simply demanding a ceasefire, not the end of the world. I am not sure the majority of people in the streets even want this world to end. I don’t know if we are ready to reckon with what a free Palestine would mean, since it would also necessitate the end of the dubious comforts of the West.

If nothing we are doing really threatens the power of politicians, we are actually offering them ways to wash their hands while remaining comfortable in the halls of power. The very structure of our protest—demanding ceasefire, asking politicians not to fund genocide—can only end up legitimizing the power we are contesting. Perhaps that’s the necessary move in dire circumstances. But imagine our demands are met: Congress condemns Israel, or even cuts aid and installs sanctions. (This might not even affect Israel’s ability to prosecute their invasion and bombardment . . . ) If that happened, these heroic politicians can be seen responding to and representing the will of their constituents, and Israel still carries on in its genocide. End of the story: our system works. The will of the people is reflected in their elected representatives. When we demand a ceasefire, we give them the possibility of legitimation. And Israel might still march on in their atrocities.

But say that’s not the endpoint. Maybe it’s a different strategy. As anarchists, we might acknowledge that we can’t expect them to listen to us, let alone give us what we want. Say the aim of the protest is another turn of the screw, to demonstrate the illegitimacy of those who govern, who claim to represent the will of the people but who blatantly ignore what we want (ceasefire, healthcare, transition, abortion, education, wages, welfare, etc.).

In some ways, this outcome has been attained by the Stop Cop City/Defend the Atlanta Forest movement, which included occupation, disruption of construction, and other direct action, but which also operated through the norms of governance and politics in city council meetings public comments, referenda, petitions and canvassing. Like Palestinian solidarity, the Stop Cop City movement is massively popular—though this is true even in its more radical tactics, which I’m not sure would be the same for those marching for Palestine. In Atlanta, they used more disruptive means and direct action, but they eventually also made sure they could point to those in power, as well as to the people who were less convinced of the need for radical action, that they tried the respected, proper channels too.

This combination of tactics resulted, however, in even more blatant attempts by the city government and the police to silence the movement. Not to mention trumped up charges for people caught in a wide net of alleged participation or even just random connection to the movement. (And now we are left with a movement committed to nonviolent direct action while the concrete is being poured in the forest.)

Is radicalization all we can hope for? When the teargas evaporated on the streets of the George Floyd Rebellion, were we simply left with proof that the cops are here to harm us not help us? Did people squatting the Atlanta forest just pave the way for a referendum to be ignored, and more people to lose faith in the electoral system? If conversion is the end of protest—demonstrations that merely skirt the edge of what is deemed peaceful or disruptive—then they may simply act as radicalizing tools, with the hope that people will be committed to amping up their actions. But does that actually happen? How long do we wait for radicalization to take hold in boldness of action? When do we stop chanting “shut it down,” and actually shut it down? If we don’t want to be in prison or dead, is there another hope?

We are caught in the readymade vocabulary of protest having either the outcome of being “heard” and thereby legitimizing the state and its functioning, or instead being ignored and proving the illegitimacy of the state. In either case, the aim of the protest revolves around the state. We hang our hopes on its action or its inaction to prove our point.

In the current moment of genocide in Gaza, we are driven by desperation. There is no arguing that what the genocide happening now must immediately stop. But the seeds of that genocide won’t stop with a ceasefire. There is no end to this violence without an end to Israel, but that also means an end to the United States, and to empire in general, including the nation state form. But beyond that, if all states fell, I fear that the racial blood feud that has been caused by Israel, and by the US, and by empire in general, wouldn’t just fall away too, even if the state and capital are the main engines of race.

*

When we want to end it all, how do we fight now? How do we not act like we are all already dead? How do we line up our actions in despair and desperation for our hopes for a better world? How do we keep up hope in the face of this wall of death that seems simply to reproduce the state form of oppression, both in the genocide and our protests? I don’t want my actions to end in condoning the functioning of the state. But I don’t want to rest on inaction, either.

The main issue with the model of protest, aimed at disrupting business as usual, is that it is still its own form of business as usual—just another protest. Those who govern aren’t threatened with any real disruption of their rule, especially when the police are in on the deal: the end of an action in planned mass arrest. Or the willingness to disperse when warned. Can we set our aims differently than begging for them to listen to us, especially when the demand for a ceasefire or stopping aid is still steps removed from Israel’s invasion and bombardment? Even the actions revolving around obstructing shipments of arms and supplies Israel, which are being more heavily prosecuted than the “nonviolent direct actions,” are stuck in desperate yet insufficient attempts at disruption, not enough to stop the grinding war machine.

Since our planned disruptions rhetorically fit the grammar of protest, we don’t threaten their ability to govern. I continually come back to the thought that our real area of resistance and rebellion must be social, not political. If we want to alter the reality of things, we cannot keep the social peace. We can’t keep (re)making their world. There have been reports from the nonprofit-led actions about the familiar phenomenon of “peace police,” those people who want to lead a protest and rein it in from anything that can be labeled “violent,” or that would exceed the contours of a respectability politics—stepping out of the role of “loyal opposition,” that Joy James articulates so well as the purview of the neo-radical. The impulse to keep a protest in line, to stop it from becoming unruly, ungovernable, is the same force that silences anarchists for being unrealistic, that keeps the organized left forming parties and plugging into elections, using our desperation for recruitment, selling papers. It’s the fear presented as cold hard fact (Realpolitik) that if we really want to achieve X goal, there is a right way to do things. We won’t be listened to if we fight the police or loot the stores. Be a good kid and go to sleep.

But does the historic combination of revolutionary violence with liberal protest still play out effectively? Do we want their reforms or concessions? All that the movements won has been eroded. Every day there are more people in the streets, closing down highways, bridges, school buildings. There are so many of us out there, and we flail in our desperation. They have begun building the police training center in the Atlanta forest while the defendants await trial. Meanwhile, cities are passing anti-masking laws, limiting possibilities of even peaceful protests, congress is voting on equating anti-zionism with antisemitism, schools are expelling and firing people who speak out. When the stakes for even minimal protest get so high, it makes every it hard for people to make the decision to take any stand at all. And the comfort of silence and routine keeps so many reined in.

For any liberation to occur, there will need to be much bolder actions taken. And I can’t enumerate them myself. We get stuck in strategy—which points do we attack? We sit and watch as more spontaneous revolts break out, and more and more people are fed up with the way things are, with not having enough, and many get sucked into the rising tide of fascism. If marches are useless because they are political, sure, they could have other possible effects. They teach us the contours of the city from a different perspective than commuting to work or home. They can provide opportunities under cover of mass to break the social peace. We pour into the streets, we draw on their walls—and we can riot or loot. Though when we start to treat the city like it belongs to us, it calls down the violence of the state upon us, it also shows them that we are ready to act up. What could we do to really take this space over? Could we hijack their concrete to our own ends?

But instead of thinking geographically, my current approach is to consider all the places we can break the social peace, big and small. I want to approach liberation this way also to get out of the politics of the mass, to stop imagining that with the right numbers surely we’ll win, they’ll cede to us. Sure, one million people out for Gaza in London is an amazing showing—and it’s beautiful to think of one million people not going to work, not shopping, congregating, sharing food outside of buying/selling. But general strikes don’t happen from Instagram posts.

My thoughts turn to this: no one who rules should be allowed to sleep at night. The first night of protest in New York swarmed Chuck Schumer’s house on Shabbos. Think of the Palestinian woman who tried to disrupt Elizabeth Warren’s dinner and was rebuffed like a child being told to behave. If we listen to them, they can have their civilized dinner and peaceful family time, while other families are killed, while everyone is desperate. They look at us like another species, like people treat the unhoused on the street, or people they deem crazy. Not even table scraps thrown to dogs. No, let’s behave like the children they think we are. Refuse bedtime and drive them to desperation for their ability to keep order. We don’t need to aim to disrupt their ability to govern, but rather show them they can’t live their daily lives in peace. If the people of Gaza can’t live, if we are forced to watch Israel murder them with the backing of the world power system—if a single one of us can’t sleep at night, neither should they.