By A. Iwasa

Synchronized Chaos

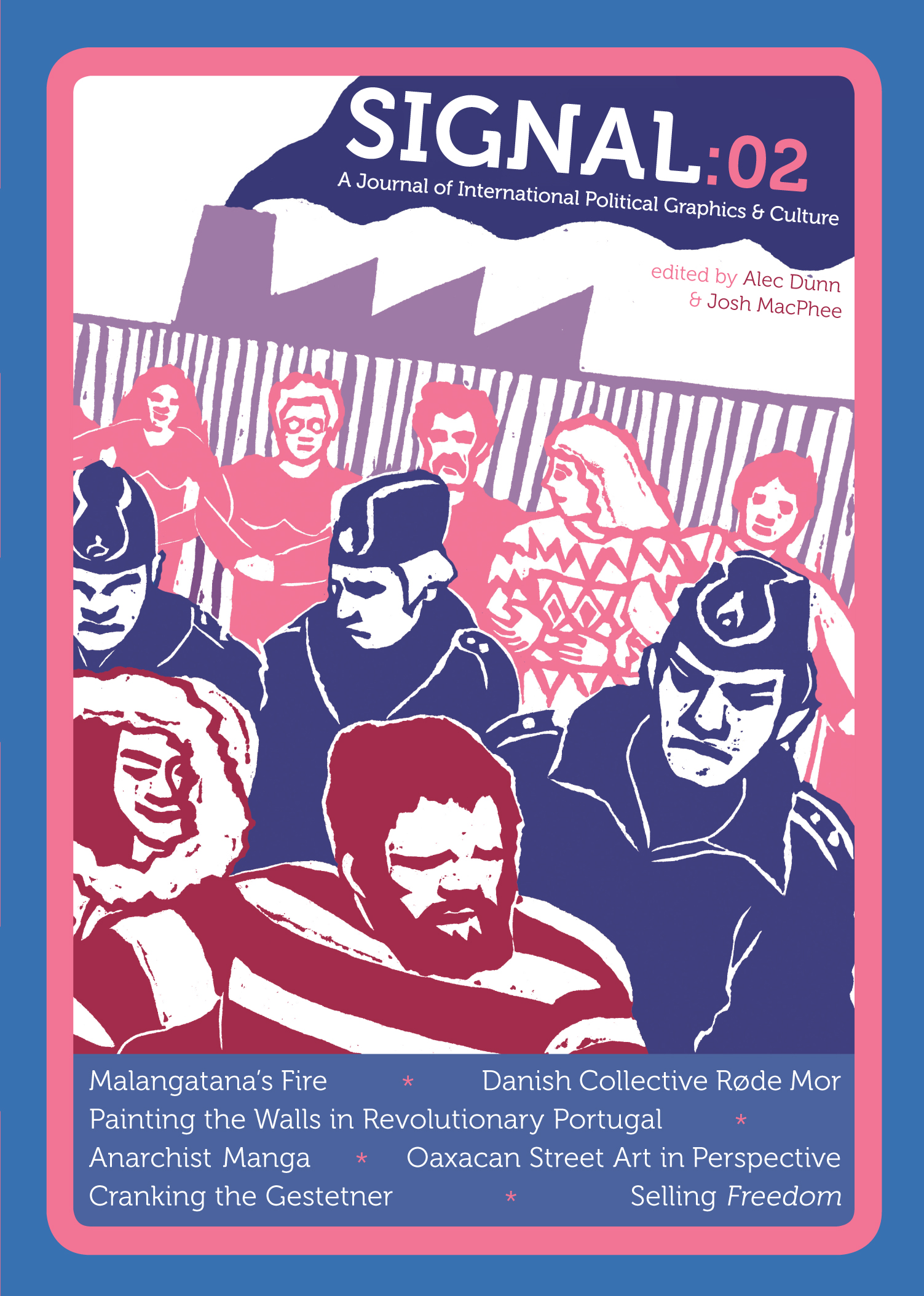

“SIGNAL is an idea in motion.

“There is no question that art, design, graphics, and culture all play an instrumental role in maintaining gross inequality. They have also been important tools for every social movement that has attempted to challenge the status quo.”

These words start the second issue of Signal, and encapsulate well what this project is about.

It’s a good mix of anarchist, anti-colonial and Left statist. Though I’ve been a long time adherent to the Anarchist People of Color (APOC) tendency, I think too many anarchists are quick to discount what we can learn from other movements that don’t synch up exactly with our theories, including other kinds of anarchists!

From an in depth essay about Mozambican painter, Malangatana Valente Nguenha by Judy Seidman, to a well explained photo essay on revolutionary Portuguese street murals by Phil Mailer, the first two feature pieces go from anti-colonialism to anti-fascist rebellion largely sparked by the Mozambican liberation struggle itself showing the potential interplay and internationalism of revolution. These connections between art and revolution are laid out sharply with images as striking as the words.

“If imperialist domination has the vital need to practice cultural oppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture,” said Amilcar Cabral, one of the primary participants in the Mozambican revolution.

Make no mistake, Malangatana paid dearly for his art, spending 18 months in jail along with writers such as Luis Bernardo Honwana, Jose Craveirinha and Rui Nogar. The Portuguese colonial authorities knew the potential power behind radical writing and art. Also, Malangatana’s brother and other family members were murdered by the counter-revolutionary RENAMO, who had been started by white Rhodesians and were later backed by the South African Apartheid regime after the triumph of the Mozambican revolution. Without a doubt, the beauty of his art was matched by how high the stakes were.

These essays are followed by a collection of images of broadsides for Freedom: A Journal of Anarchist Communism, an English publication co-founded by Peter Kropotkin among others. The collection was found at the Kate Sharpley Library, driving home the importance of archives.

This is followed by a deep dive into old school, low end printing technologies by Lincoln Cushing, what Cushing calls “the Volkswagen bugs of the reproduction world.” Printing was my vocational in high school, and I worked in the industry on and off from 1998 to 2022, so this one was particularly fascinating to me.

Though Cushing writes a bit about different kinds of offset and letterset presses, and pre-Xerox copy machines, this is primarily about Gestetner Art. Again, this was especially interesting to me as the San Francisco Diggers were very involved with the Communications Company which had two Gestetners, the only reason I was already familiar with this sort of machine. The essay focuses largely on their break through work in color separation, something most people take for granted today.

Cushing remains largely focused on the San Francisco Bay Area, but goes on to write about various other print projects that used Gestetners. It’s a solid snapshot of an era, but it’s also inspiring as I’ve not only worked in the printing industry but have also volunteered for various print projects over the years.

I don’t think the past stands as a blue print for what we should do now or in the future (I mean, look where it got us!), but I do think we should gather inspiration where it makes sense to try to add to successes from the past and move forward. For many reasons I don’t think you can duplicate proceeding events anyways.

Next is an article by Deborah Caplow that situates the then contemporary Oaxacan street art into the larger context of Mexican Revolutionary art starting in the 1920s.

I was possibly most excited to learn about the Liga de Escritores y Artistas Revolucionarios (LEAR, League of Revolutionary Writers and Artists) since I’ve long been interested in organizations for cultural workers beyond the small scale collectives and what not I’ve been able to participate in.

Though I was also fascinated by what I read about Jose Posada as a longtime fan of his work, but simultaneously unknowledgeable about him as a person.

This is followed by a Manga by Taiji Yamaga, a participant in the early Japanese anarchist movement. It’s introduced by the Center for International Research on Anarchism, Japan. I was dissappoined at first, because when I read Manga, I instantly went to Death Note in my head was hoping to have discovered the Japanese Philip K. Dick or what have you. The Yamaga Manga is essentially just drawings and notes for his memoires, The Twilight Journal. But it’s still cool as a first person account of anarchism in Japan in the early 1900s, especially to me since I’m half Japanese but don’t speak the language.

In closing is an essay about Rode Mor (Red Mother), a Danish collective from 1969-’78 that evolved from a graphic workshop to a band, then a circus split off and ended as a fund artist-activist projects.

The author of the essay, Kasper Opstrup Frederiksen, translated all of the titles and quotes, which to me shows a certain level of expertise on the subject matter the editors seem to do a good job of finding, when they don’t have direct participants’ input.

The article delves into Rode Mor’s philosophy, practice influences, which was largely Socialist Realism. Though Rode Mor stopped cultural production in 1978, that’s when they pivoted to using the profits from their work to fund other Danish Leftist artists until 1987.