By Sena Christian

Sacramento News & Reviews

On a recent Monday morning, with finally a break in the rain, Josh Fernandez and Frank Stockton met for the first time at Barrio, a coffee shop in Sacramento.

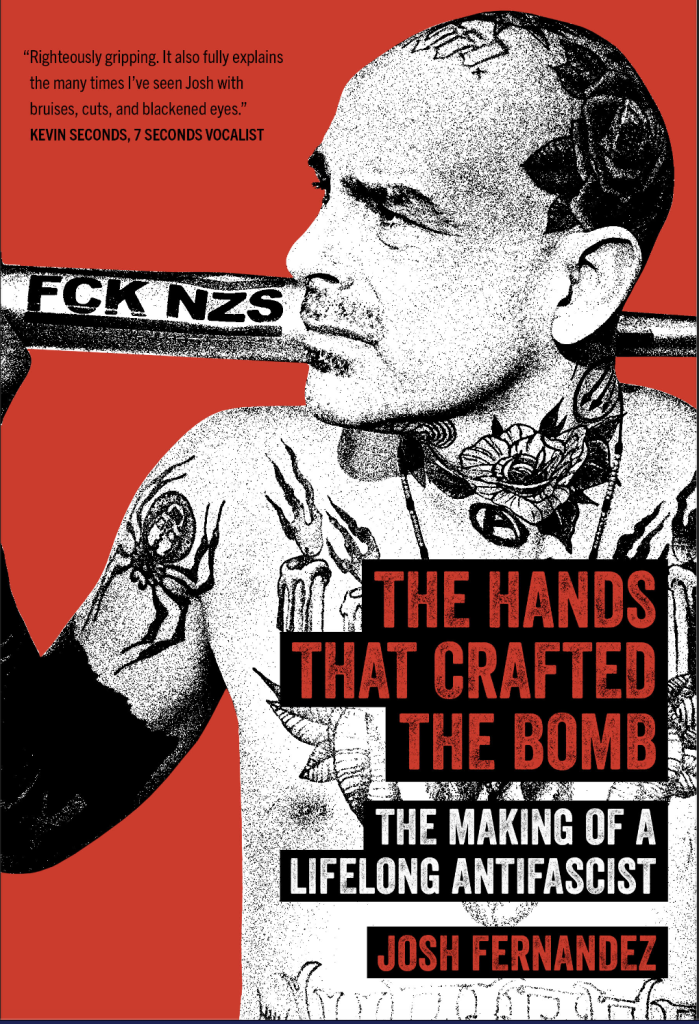

Fernandez has been kicking around Sacramento since 2000. He authored “Spare Parts and Dismemberment,” a poem collection, writes for The Hard Times and his memoir, “The Hands That Crafted the Bomb,” about his life as a anti-facist, is set to be released by PM Press this fall. He also teaches creative writing at Folsom Lake College.

Born and raised in Southern California, Stockton spent time in New York City and Los Angeles, freelancing for media outlets and painting in his studios, before moving to Sacramento in early 2022 to be closer to family. His work has appeared in multiple solo shows and exhibitions around the world.

Fernandez and Stockton talked about their art (and responded to questions provided by a reporter). Here’s a condensed version of their conversation.

Fernandez: What are the main challenges you face in your artistic work?

Stockton: The main challenges in being an artist and creative work are just time, space, and then the mental and emotional weight or load that being an artist requires.

Fernandez: Do you have an emotional reaction when you create stuff?

Stockton: I’m super emotional. … We’re all sort of wired differently. I’ve seen some people create something, make a drawing, and then they are predisposed to feel really bad about it. Other people are predisposed to feel really good about it. And there’s artists of both types. Usually, it’s a few days later, you have time to step away and you come back and see with clearer eyes. … Sometimes you come back, and I’ll feel embarrassed about how good I felt when I finished something. Like, this is crap. What are your challenges?

Fernandez: Especially writing a memoir, the heavier scenes, I’d write it and in the moment, I’d be fine with it. But then stepping away I’d feel this horrible weight of depression and anxiety. I started to have panic attacks. I started going to therapy. I think part of it was because of the creation of that memoir, just reliving all these traumatic things.

Stockton: Do you think it was reliving the trauma or was it related to putting it down? Or the fact it was going to be public?

Fernandez: When I was writing it, I honestly did not think it would be published. So I think it was just putting it down, stamping it down the page. Then after, I realized I’d written a book. And I was like, OK, I’m gonna send this out, and then the fear of rejection for me — it’s weird. With my poetry book, I didn’t really care if it was published or not. But with a memoir, it’s your whole life and then if it’s rejected, it’s a really personal feeling. So there was this real panic I had about getting published or having some sort of validation.

Stockton: I can relate. It’s hard to get yourself into the place to exercise whatever is bubbling that you need to come out. That’s struggle No 1. Struggle No. 2 is then sharing it with the world somehow, which is putting yourself up for rejection and misunderstanding, all kinds of consequences attached to caring. Do you feel that making the work itself — like say it didn’t get published — is still valuable to have put it down?

Fernandez: Yeah, I think so. It’s the craft. I would do it regardless. I feel something inside of me, and I don’t know what it is, but I want to create stuff. I have no visual artistic talent. I’m not a musician. But this is one thing I can do and this is how I have to let it out. If I had never gotten published before I’d still do it. What about you?

Stockton: Absolutely. You kind of have to have that mindset. Because the work wants to be a certain way. I suspect it’s a misconception for a lot of people that artists make a decision about how it’s going to look and how it’s going to be, but one of the lessons I keep relearning in my adult life is that the work just comes out a certain way. … My work has changed a lot over the years. One of the things I’ve found from the work changing so much is that people aren’t always on board.

Fernandez: That’s good, though, right?

Stockton: Yeah, I think so, I think so.

Fernandez: When I was thinking about [a question related to] Sacramento’s creative scene, I don’t know about it. I don’t even care about a scene. I don’t want to be in a scene and I think I’ve produced better or been more creative when there’s no scene at all. I have some friends who get all these government contracts to do art. I feel like that would be the death of me. Like if the government was paying me to do art projects, I don’t want to do that. The second the government tries to give me money for an art piece, I feel like I need to quit. I feel like when the scene is dry — there’s nothing, there’s no money — that’s when I thrive.

Stockton: I’ve been visiting Sacramento since 2007 and I’ve only lived here for a little over a year, so I’ve been getting acquainted with the art scene. Before I moved here, I was living in LA and I was talking to a friend of mine, an amazing painter, and I was like, I’m moving to Sacramento. I was just talking about trying to get to know other artists around here. And [my friend] was like, “Maybe you’re better off just not talking to any artists and just meeting some local weirdos.” … Generally, the artists I’ve met feel frustrated, like they want a better scene. … I feel like the Sacramento art scene desperately wants to be taken seriously. I think that’s to its detriment.

Fernandez: I think so too. It’s this weird complex Sacramento has. It’s not San Francisco. It’s not LA.

Stockton: It’s always becoming.

Fernandez: Yeah, it’s always becoming. Like, we’re almost a world class city.

Stockton: Sacramento’s digital art scene is super well organized. There’s all these events where they invite everyone to get together and everyone has a seat at the table in a sense. Sacramento has a lot of hobbyists, and it’s got a handful of really interesting artists, from my perspective. Most of them don’t go out to the openings, the ones that I’ve met. A few of them do, but most of them stay in their studio.

Fernandez: The second question is tell me about any moments when you felt close to giving up on your art?

Stockton: I’ve never felt that.

Fernandez: Not even close?

Stockton: Between an 18-month stretch recently where I had to pack up my LA studio and then moved to Sacramento that basically took me out of [a studio] was a dark place. But since I was in second grade. I’ve always been like, I’m gonna be an artist. … It’s not a good thing necessarily. It feels like a curse. I had teachers coming up that would say, if you can imagine yourself doing anything other than art, you should do that. I used to think, what an asshold thing to say. And now, man, I cannot do anything. It is what it is. I accept it. I love it.

Fernandez: I tell that to my students all the time. I have no other skills. I dropped out of high school. I stopped taking math in like the third grade. I can barely tie my shoes. I just read a lot when I was a kid. I love to write. And that’s it.

Stockton: Is there a book or something you read that set you on that path?

Fernandez: When I was little, I would just skip school and go to the library and I would read everything. I started with fantasy. I would read the Boy Scout magazines, and I wasn’t a Boy Scout. I was voracious when I was a kid. It was an escape for me. It was an escape from everything. The only time I felt like giving up on my art was when I first got hired as a writing professor. I was so dedicated to work. I was really proud of myself … and I started to identify as a college professor. I was working so much, I completely stopped writing. … And I just felt this void.

Stockton: The third [question] is how do you make a living through creative work?

Stockton: Making a living as a creative, I think of it as like spokes on a wheel. You have to have several spokes for that wheel to go around. So there’s teaching and freelance and selling original work. Something needs to support the art. It’s super rare that the work can support itself. I do a lot of commissions for magazines. But it’s not my work. It’s a creative vocation I’ve learned how to do. I’m grateful for that. Before I moved to Sacramento, I was doing a lot of teaching. I miss that. What about you?

Fernandez: Now I just teach writing. It’s funny, though, when I sold my book, my wife and I got into this argument, because I was just going to go with the first press that said, Yes. She’s like, you have to weigh all your options because this is money that affects our family. I didn’t think about it like that. … I don’t think about it in terms of selling. So it’s really weird to realize there’s some serious aspect of financial stability that comes with this.

Stockton: Now I’ve got two kids and I’m freelancing, and the freelancing lifestyle is very incompatible with raising kids and being an artist. I’ve got nothing left at the end of the day when my kids are asleep and it’s time to go into the studio.

Fernandez: Let’s see. Why is the artwork you do important? Why should anyone else care? I don’t know if anyone else should care, really. I mean, I feel like I care. People need to feel things and I can facilitate that through my art. I know just through trial and error and publishing a bunch of stuff that the things I write have the ability to make an impact. A lot of it is laughter. I love when people laugh. If I can write something that makes someone laugh or feel some sort of emotion that’s outside of their phone or outside of a screen, I feel like I’m doing a good thing.

Stockton: On some level, you have to believe people care. I don’t pander to what I think people want to see. I don’t pander to what I think is gonna sell. I wish I had that in me sometimes. But it comes out a certain way. Sometimes people don’t like it, and they misunderstand it, and that’s always a fear. … The answer to that question is faith.

Fernandez: When my editor read my book, the first thing she said was, a lot of people are gonna be really unhappy after they read this with you. I took that as a compliment, just because it challenges ideas.

Stockton: I was doing an artist residency in 2015. We’re in a cabin in the woods for a couple of months, hanging out, just talking with other artists. It was amazing. I had a really esteemed colleague come by and asked me about my work. Gender and sexuality and masculinity were coming up in the work. Not everybody likes having those in there. They look at you and then they look at the work and leap to conclusions about what it means. I don’t make work that I think is didactic. I’m not trying to give someone an opinion. [This colleague] was saying you bring up all these things that are gonna potentially upset people. … I’m not like saying this is what it’s about. But I’m really just presenting something for you to chew on, roll over in your head and think about.

I had a friend who did a controversial painting … and asked what is the value of painting that? My response is: What the painting does is it can take an ugly subject and make it beautiful, not to change your mind about the subject. If I see a gory photograph, my knee jerk reaction is to look away as soon as possible and get away from this ugly thing I don’t want to think about. If you show someone a beautiful painting about an ugly subject you seduce the viewer to stand there and confront it.

Fernandez: In teaching writing, the subject always comes up about trigger warnings. How do you feel about that?

Stockton: In the [academia] environment, I always try to be really respectful of those types of things. … I get triggered all the time. I’m OK with it. I’m a little older, so I’m like, being triggered is normal.

Fernandez: I grew up triggered, man! (chuckles) … My book went through a sensitivity reading. That’s what happens with books now, they go through sensitivity readings. And my book did not pass the test. They send you back a list of all the things that could be triggering to people.

Stockton: But the work has to come out. In 2019, after my dad passed away, I started making major stylistic shifts in the work I was doing and started running toward an aesthetic specifically that I knew would turn off a lot of [people]. But you have to follow the muse. Since 2019, I’ve been making this work in secret and being afraid people aren’t going to like it. … I finally started getting enough courage to share some of it, and the reactions have been what I feared. … When you follow the work where it needs to go and if your work changes a lot, and it’s taken me a long time to come to grips with: I don’t have an ‘art style.’ I think all the work looks like mine. If you look at a Picasso, well, Picasso’s the worst offender. If you look like Warhol, a [Agnes Martin], a Pollock, you know what to expect. If people are changing a lot, people have a hard time keeping up with it. [There] are the people that stay along for 20 years for the evolution.

Stockton: Do you have a plan [with your art]?

Fernandez: When I see super successful people and I see the way they plan their lives, I can’t do that. I have no plan. I have nothing. All I do is just write. And whatever comes out of that is fine.

Stockton: I totally relate. But when it comes to other artists, I’m like: You have a chance to get money; get your money.

Fernandez: Totally. Everyone always makes fun of David Garibaldi. I don’t know if you’ve seen him. He splatters paint on a wall and it turns into a painting. He was on “America’s Got Talent” and he drives, like, a Lambrogini around town.

Stockton: This sounds like something someone sends me an Instragm story or Tik Tok of. I’m like, I don’t know what to do with this.

Fernandez: Exactly. Everyone is like “F—” this guy, he’s not a real artist.” But, I mean, he’s just a guy making money, throwing paint on the wall. If I could do that, I’d do it.

Stockton: Before when you were assessing your skills and telling your students you don’t have any skills, well, being able to fulfill a commission and do what people want that’s a skill in itself. With the guy splattering paint on the wall, it’s a stew that makes the individual work. I don’t have one of the major ingredients: shame, standards.

Fernandez: A Lamborghini.

Stockton: I don’t have a Lamborghini either. Maybe if I had a Lamborghini, I’d feel differently.

Fernandez: Yeah, probably.

Stockton: With people who become successful in the fine art realm … [their] financial success is wild. It’s easy to hate on people. I try not to hate on people for their success. It’s not a good mental state to be in.

Fernandez: It’s not. Their success doesn’t take anything away from me. But it’s still a little fun to hate on people sometimes.

Stockton: The best solution is to go back into our studios and shut the door and ignore the world. That was one of things I was excited about being in Sacramento. Being in LA and before that New York I felt super aware of what everyone else was doing. I was so plugged in, and it was a little like there were too many voices in the studio.

Fernandez: You’d think it would be the opposite. You’d be in these inspiring places, these bustling hubs for artistry.

Stockton: In a way, you cede your tastes being in those places.

Fernandez: Those places are better for audiences than for artists. In 2008, when I worked at the News & Review, it was bustling art here. There was art everywhere and it was full of self-important people. Everything was art and everyone was dressed all cool. I don’t know what happened, but it kind of stopped and I felt like I can breathe again.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

This story is part of the Solving Sacramento journalism collaborative. Solving Sacramento is supported by funding from the James Irvine Foundation and Solutions Journalism Network. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19.