By Adam Sear

Tradfolk

October 17th, 2023

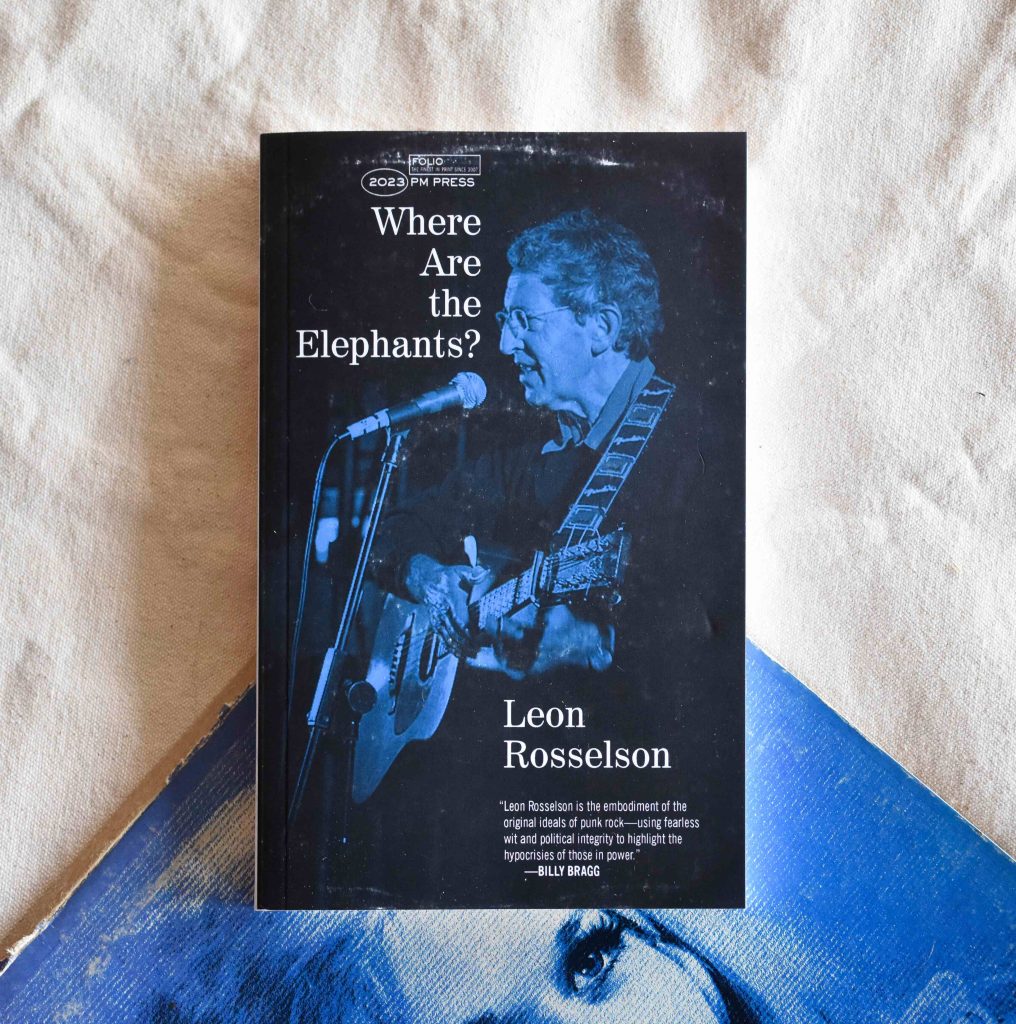

Explore Leon Rosselson’s protest-driven folk music journey in this compelling compilation album featuring collaborations with iconic artists.

Release Date: 27 October 2023

Leon Rosselson’s compilation album offers a retrospective of his lifelong protest-driven career. Collaborating with legends like Martin Carthy, Billy Bragg and Frankie Armstrong, Rosselson’s thought-provoking songs tackle issues from anti-war sentiments to social justice. The collection showcases his evolving style and enduring passion, making it a captivating primer for new listeners.

BUY ONLINE

Click here to order the album online

In 1649

To St. George’s Hill

A ragged band they called the Diggers

Came to show the people’s will…

Many Tradfolk readers will know and love this song. It’s by guitar-wielding man of the people, left-wing firebrand Billy Bragg, right? Well, you’re almost there – replace Billy’s name with that of almost-nonagenarian songwriter and, latterly, celebrated children’s author, Leon Rosselson, and you’d be one hundred per cent correct.

Following his contribution to the British folk revival of the 1960s (both solo and with The Galliards), he became known for composing and singing topical songs on the BBC’s legendary satirical show That Was The Week That Was. Active in the recording studio since 1960, Rosselson has a rich back catalogue – his most recent solo album being 2016’s Where Are The Barricades? The title track, included here, poses the key question of our times – “Capitalism’s in crisis, but where are the barricades?”

This new compilation, handpicked by the man himself, is both a fine career retrospective and an excellent primer for newcomers. ‘The World Turned Upside Down’ (1974), quoted above, is the centrepiece and beating heart of both this collection and Rosselson’s entire career. His compelling take on the beliefs and sorry fate of the activist Gerrard Winstanley, and his fellow Diggers, welds Winstanley’s own words to a melody for the ages, still sung at protest marches to this day. Where Bragg’s version is acerbic, Rosselson’s is almost gentle, its fire carried in the rousing words and undeniable melody.

Protest is the key driver of Rosselson’s work and anti-war songs recur throughout the decades. In ‘Across the Hills’ (1964), he sings, “Across the hills, black clouds are sweeping, carry poison far and wide,” eloquently expressing the decade’s deep anxiety about the threat of nuclear war. A lightness of touch and sardonic wit tempers the seriousness of his material – a live recording of ‘Stand Firm’ (also from 1964) delivers Woody Guthrie-style picking and an audience laughing in the dark as Rosselson scorns the UK government’s risible advice in the face of impending nuclear disaster. He revived the song in the 1980s to pillory the Thatcher government’s endlessly mockable civil defence handbook, Protect and Survive.

Moving through the decades we arrive at ‘General Lockjaw Briefs the Troops’ (2004). Over deft, jazz-inflected guitar, Rosselson delivers a short and biting song about the lies and propaganda used to promote the USA/UK-led invasion of Iraq. His character, General Lockjaw, imagines the gratitude of all the liberated Iraqi people – “Except for the ones whose heads have been blown off.” Later, on ‘Talking Democracy Blues’ (2011), Rosselson tackles the importance (and infrequently disappointing consequences) of exercising our democratic franchise – “War after war, that isn’t what I voted for.” He reserves much of his ire for Tony Blair – “When he smiles, children die…” – and sings again of Iraq, “A country smashed and devasted…”. Yet Rosselson contains multitudes and often deploys more subtle approaches to exposing society’s ills. On ‘She Was Crazy He Was Mad’ (1967), over a sequence of gentle folk-jazz changes (reminiscent of his contemporary, Jake Thackray) he meditates on what it really means to be insane, coming firmly to the conclusion that building and deploying weapons of mass destruction is the truest expression of madness.

The spirit of the 1960s doesn’t escape Rosselson’s forensic scrutiny and on ‘Flower Power = Bread’ (1968) he takes on sacred cows – The Beatles themselves. The song opens with the first few bars of ‘La Marseillaise’ which, in the late sixties, can only refer to one globe-straddling tune. Over dexterous arpeggios, Rosselson gently sends up the idea that all you need is love. Peace and love, laudable intentions as they are, are not enough for this activist. Listening to the chorus, I can’t help wondering if it lent a little inspiration to The Rutles’ 1978 track ‘Love Life’– “Love is the meaning of life, life is the meaning of love…”. It’d be a satisfying symmetry, if so.

Rosselson never lost his topical touch, sharply honed on TW3. ‘Ballad of a Spycatcher’ (1987) sees him craft a jauntily provocative response to the government’s banning of former MI6 man Peter Wright’s expose of the security services, Spycatcher. Like Blair, Thatcher is a recurrent bête noire, and she makes an appearance here. Assisted by admirers Billy Bragg and Oysterband, he sings, “Nanny thinks it wouldn’t do for you to know about the naughty things the spycatchers do…” as he flouts the ban, quoting snippets from the forbidden book.

Aside from ‘The World Turned Upside Down’, the standout track for me is 1986’s ‘Bringing the News from Nowhere’. Assisted by legendary guitarist Martin Carthy, singer Frankie Armstrong and frequent collaborator Roy Bailey, Rosselson pays tribute to nineteenth-century poet, artist and social activist, William Morris. A beautifully arranged brass section underpins stirring, hopeful words:

I like those who come with the passion of a vision,

Like a child with a gift, like a friend with a question

William Morris was one…

See also

Tamsin Elliott, FREY – a review

…honour to this man and honour to the dreamers

the other men and women the history books ignore

Who would not turn aside for honour and position

But held to the hope and the vision that they saw.

There is – understandably – a less strident, more autumnal feel to the later songs. Rosselson loses none of his passion, but his voice, tempered by age, harbours a more reflective quality. Opening track, ‘Song of the Old Communist’ (1991), sets the tone for the collection. If you don’t know Rosselson’s music, the first thing to strike you is his cleanly enunciated North London voice – here is a man who can only be his unvarnished self. Singing from the point of view of the titular aged Leninist, he manages to make the character both sympathetic and comprehensible. Over a spidery, subtly melodic acoustic guitar, he points a righteously angry finger at “you who have nothing at all to believe in, you whose motto is Money Comes First…”

The demise of the Communist experiment is also lamented in ‘Wo Sind De Elefanten?’ (1990), a strangely touching guitar and vocal performance which ambivalently documents the collapse of the Berlin Wall. Despite this pessimism, Rosselson expresses some hope for a more equitable world in ‘Postcards From Cuba’ (1999), a sweet reflection on a trip to the island, packed with real-life incidents. As Rosselson’s careworn voice intones the sentiment that Cuba is “an idea in the mind… the spirit of defiance…” the song is brought to life by warm Cuban horns and deft rhythms, dexterously played by an ensemble that includes Robb Johnson and, once again, Martin Carthy.

This is a fine collection, and you don’t have to share every detail of Rosselson’s worldview to enjoy it. He sets out his stall articulately and the listener is invited to reflect upon his powerful, often persuasive words. Like his hero William Morris, Leon Rosselson has always held to the hope and the vision that he saw.