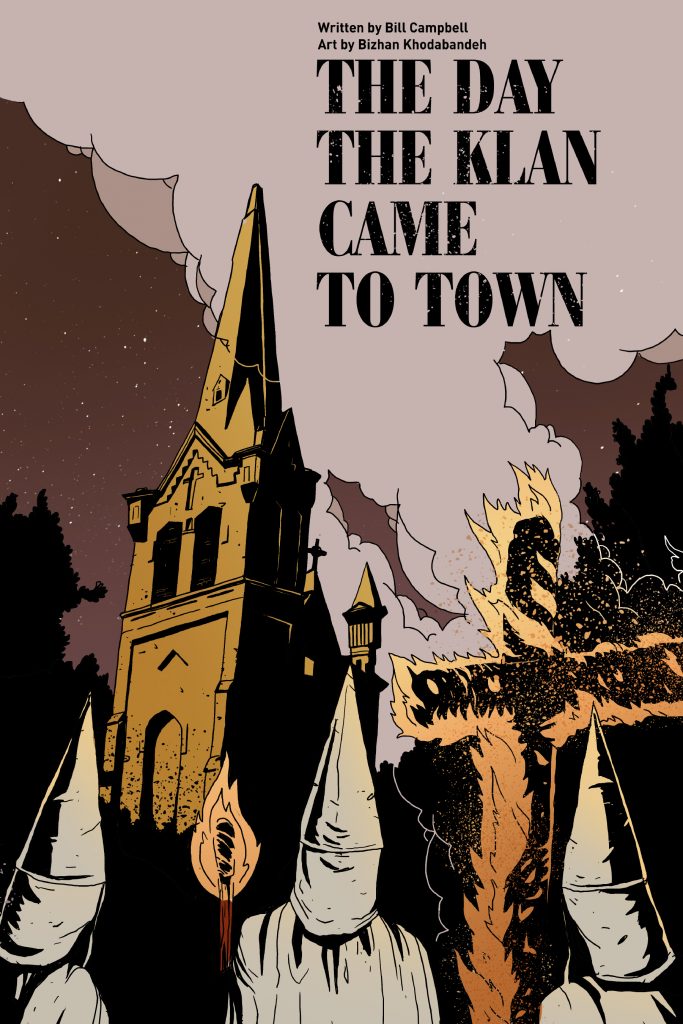

As I reread Bill Campbell and Bizhan Khobabandeh’s The Day the Klan Came to Town (2021) recently, my mind kept coming back to another book I have been reading at the moment, Robert O. Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism (2005). Campbell and Khodabandeh’s graphic novel tells the story of individuals in Carnegie, PA, standing up against the Ku Klux Klan’s planned march through the borough of Pittsburgh where Jews and Catholics, Irish and African Americans and Italians lived. The Klan, after initiating 1,000 new members, gathered for the “Karnegie Day” march through the borough. They defied an order not to march, and they were met by citizens who blocked their path and conflict ensued, leaving multiple people injured and a Klansman dead. The Day the Klan Came to Town is a fictionalized account of August 25, 1923, and it follows, for the most part, Sicilian immigrant Primo Salerno as him and the other citizens confront the Klan.

Two page at the beginning of the narrative appear in stark black and white tones with no clear indication about who the individuals are within the panels. The first full page panel shows men in car, hooting and hollering as they hold guns aloft, chasing another man down the street. The first two panels on the next page show the car hitting the man. The middle panel is a long, horizontal panel. It shows the men that were in the car lined up. They are all black and the weapons that they hold in their hands are stark white. Four men hold guns and one holds a knife. The man with the knife tells the others, “Now, fellas, here we are, out on a coon hunt, and we done caught us a guinea instead.” Here, we know that the man they run down is Italian. The final two panels show a closeup of the man holding the knife beside his face as he smiles villainously at the victim and the final panel shows the man’s hands over the victim’s mouth. On the next page, we learn that this has all been a dream as Primo darts up in bed.

In 1915, Primo, while gets pulled, as a teenager, from working in the sulfur mines in Sicily to fight in World War I. Following the war, we see Primo back in Sicily in 1920, sitting on the street, out of work, and drinking. The fallout from the World War I, specifically the fact that Italy did not gain anything from their connection with the allies, led to high unemployment, inflation, and social unrest, all of which led to the rise of the Partito Nazionale Fascista. Two women, one pushing a baby stroller, and a man walk by Primo as he sits on the street. The man, wearing a black shirt, glares down at Primo, pointing his finger angrily at him. The young woman returns and speaks with Primo, and as she talks with him, the man, who appears to be an early iteration the Blackshirts, comes back with a group of men and interrupts the conversation.

The man tells Primo that only the Partito Nazionale Fascista and Il Duce Mussolini “can take that maimed victory of war and turn it into a real fascist triumph!!!” Then, the man and those with him, attack Primo, punching and kicking him in the street. As Primo lies bloody on the ground, the man tells everyone who beat up Primo, “Gentlemen, you are the true trincerocrazia. Not this ‘hero’ of Caporetto.” This attack leads to Primo leaving Sicily for America, and this attack, along with other things, leads Primo to serve as one of the leaders in Carnegie who stands up to the Klan.

What caught my attention here with Primo’s story was not so much the fact that he comes from Sicily or that he is an immigrant. No, what caught my attention was that Campbell and Khobadandeh depict, albeit in a very condensed manner, the rise of fascism in Italy and present it in connection with the Ku Klux Klan through Primo’s narrative. They do not explicitly call the Klan fascist, but the framing with Primo makes this connection clear in various ways.

When I read Primo’s backstory, I went directly back to something I had just read in Paxton’s The Anatomy of Fascism as he talks about the creation of fascist movements. There, Paxton points out that while scholars debate about where we can see the earliest forms of fascism (Russia, France, etc.), perhaps “the earliest phenomenon that can be functionally related to fascism is American: the Ku Klux Klan.” Paxton notes that the initial Klan’s appearance following the Civil War “constituted an alternate civic authority, parallel to the legal state, which in the eyes of the Klan’s founders, no longer defended their community’s legitimate concerns.” Through the creation of militias, the connections with local governments, educational avenues, and more, the Klan hit numerous aspects of fascism, and The Day the Klan Came to Town highlights some of these.

The first Klan arose to maintain white supremacy, to prevent African Americans from gaining their full citizenship following the Civil War. The second Klan, which arose during the early twentieth century, arose on the same pillars and expanded its hatred to others such as immigrants, Jews, and Catholics. Paxton argues that we can define fascism “as a form of political behavior marked by an obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity” which all has buy in and collaboration with “traditional elites” and exchanges in violence to uphold its values. The Klan fits this definition in every manner, as we see from the splash page for chapter 1 in The Day the Klan Came to Town where a Klan member is spouting xenophobic and racist rhetoric in front of the United States Capital.

Fascism thrives when the fascist party runs parallel organizations to the ruling party such as youth organizations, paramilitary groups, private groups and more, leading some of them to become subsumed into the fascist regime. The police became a key agency in exerting control over the state. This occurred in Nazi Germany with the Sturmabteilung (SA) which served as a paramilitrary force. The Schutzstaffel (SS) arose out of the SA when the Nazis took control, and the SS became the state police force under Heinrich Himmler. The SS came under control of the Nazi Party, but in Italy, the police remained under a civil servant, Arturo Bocchini.

The Blackshirts in Italy, to which the man who attacks Primo belongs, were the Partito Nazionale Fascista’s Squadrismo, or their paramilitary wing. In the years following World War I, the Squadrismo, as Paxton puts it, “succeeding in demonstrating the incapacity of the state to protect the landowners and maintain order.” This same feeling corresponds to the Klan who came about under the auspices that the government had left whites and the South behind in favor of African Americans following the Civil War.

Again, we see this is The Day the Klan Came to Town. Most importantly, we see it in the use of the police force to further the Klan’s actions on “Karnegie Day.” When John Conley, the Burgess of Carnegie Borough, stops the Klan members from marching, Chief Keisling, the chief of police, allows them to continue. We see this moment in a four-panel page where a Klan member tells Conley that he’s infringing on their first amendment rights, and then the Klan member turns to the chief and asks him to agree. Keisling then tells Conley, “Sorry, Burgess, it would be illegal to stop them. I’m the chief of police. I am here to enforce the law. I can’t be breaking it, now could I?” The next panel shows Conley turning away in disgust. Behind him, Keisling winks and smiles at the Klan member, showing his role within the march, as a facilitator and as an insider working within the walls of the law, the police serving alongside the Klan in their goals.

Along with all of this, it is no surprise that such an event happened in Carnegie, PA. In his article “‘It Can’t Happen Here’: Fascism and Right-Wing Extremism in Pennsylvania, 1933–1942,” Phillip Jenkins notes that “between 1923 and 1935, some 432 Klan lodges” appeared in Pennsylvania, and the most, 33, appeared in Allegheny County, where Carnegie is located. As well, following the events in Carnegie and in Scottdale, “the Klan formed a paramilitary corps of ‘klavaliers.’” Philip Jenkins notes that at this time as well that Klan membership in Pennsylvania was probably over 250,000 and that nationally it exceeded 5 million members. Elsewhere, Jenkins points out that the klavaliers dresses in “white military uniforms and black leather puttees,” and they served as “police, sergeants-at-arms, and leaders of the vanguard in conflict with hostile groups such as Catholics.” The klavaliers were the Blackshirts or the SA. (You can see a klavalier membership card at the Social Voice Project.)

There’s a lot more that I could say here, and I probably will at some point as I continue to dive into these histories. However, I want to leave you with this. At the end of the book, Primo and the men, women, and children who stand up to the Klan celebrate in the streets. Someone says, “People will remember what we did here tonight.” The final panel shows Primo hugging his wife as a women stands to the side amidst broken glass, the crowd is silhouetted in the foreground looking at them. One of the crowd members says, “We Americans love forgetting. It’s how we keep doin’ what we do.” The final line serves as a warning because forgetting is not an option. When we forget, we allow the festering sore to reopen, spilling out the past into the present, causing reprehensible harm to democracy. The Day the Klan Came to Town reminds us that we must not forget, and that we must be aware of the connected tentacles that conjoin fascism and hate across the globe, not just is pockets here and there.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.

Back to Bizhan Khodabandeh’s Artist Page | Back to Bill Campbell’s Author Page