By Matt Peterson and Malek Rasamny, for Lundi Matin

Matt Peterson and Malek Rasamny, who co-edited The Mohawk Warrior Society: A Handbook on Sovereignty and Survival, directed the feature-length documentary film Spaces of Exception, which will have its North American Theatrical Premiere at New York’s Anthology Film Archives this October 27-31.

Spaces of Exception features interviews with members of the American Indian Movement, the Mohawk Warrior Society, and Diné families resisting displacement on Black Mesa, as well as members of Fatah, Palestinian environmental and media activists, autonomous youth committees, and the families of political prisoners and martyrs. The film investigates and juxtaposes the struggles, communities, and spaces of the American Indian reservation and the Palestinian refugee camp. It was shot from 2014 to 2017 in Arizona, New Mexico, New York, and South Dakota, as well as in Lebanon and the West Bank. Spaces of Exception is an attempt to understand the significance of the land – its memory and divisions – and the conditions for life, community, and sovereignty.

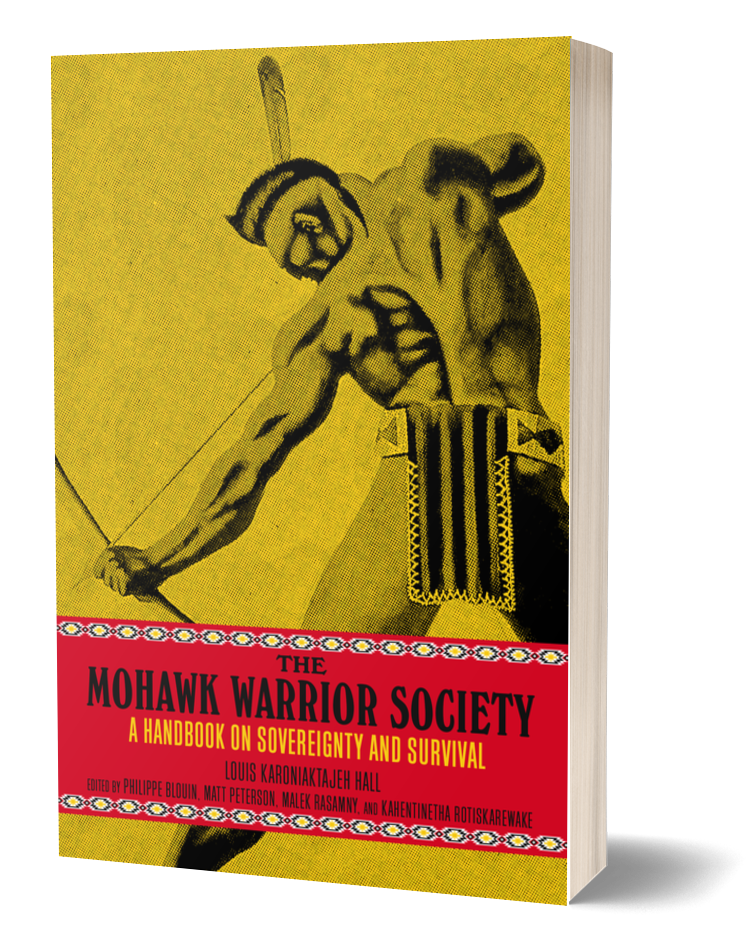

The film will screen alongside a retrospective of 6 of their short films from The Native and the Refugee project, and the series will conclude with a special screening of Alec MacLeod’s 1992 documentary Acts of Defiance, featuring some of the participants from The Mohawk Warrior Society book.

Spaces of Exception comes out of the long-term multimedia project The Native and the Refugee, which has been presented in Canada, Denmark, Ecuador, England, France, Guatemala, Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Portugal, Syria, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates, within the refugee camps and reservations were the film was shot, and at venues including cinemas, museums, and universities. https://thenativeandtherefugee.com/ The following interview was originally published in French by Lundi Matin (https://lundi.am/Espaces-d-exception-entretien).

Can you tell us more about how you two met and what were the original intentions behind this film and the media project ? (Tell us more about your positions, anchors and relationship to these struggles)

We met 10 years ago in New York, after regularly running into each other at both radical political spaces and experimental film events happening around the city. Soon after we were in a collective together, Red Channels, that continued this combination of film and politics – organizing screenings, discussions, situations around the city. The Native and the Refugee was a continuation of that practice, creating a platform to do political work together, but with an experimental, interdisciplinary, multi-media approach – working with many collaborators to help film, edit, and participate in public discussions.

We grew up in New York and Beirut, and are neither indigenous nor Palestinian, but were interested in how the Indian reservations and refugee camps exist in and around where we’re from and live, but are governed differently. Their identities are produced and maintained by the state, and are positioned in society as other, external, foreign, taboo, unknowns. We wanted to visit these “spaces of exception” precisely because of this, because people usually don’t know how to enter a refugee camp or reservation – do you need permission, who do you meet, what do you ask, what do you bring, what do you want to know, what is possible to discuss and build together? This is where the project came from, asking these questions as a way to understand what the nation-state and citizenship really are, by thinking about where and who is excluded.

An important link in the project is how territory frames the ideas of sovereignty in both struggles. For most of the indigenous nations located territorially inside the borders of the United States, a land base is an essential component of their articulation of sovereignty – being politically, socially, economically, and spiritually outside the American system of governance – and the reservation is often the official articulation or potential starting point of such a land-base. In the United States claims of sovereignty are almost inevitably tied to land claims, and this has brought conflict with state power in North America. The Palestinian camps, on the other hand, are the spatial embodiment of a form of sovereignty rooted in refugeehood. It is refugeehood itself that is the threat, because it upends the sanctity of the State of Israel by calling attention to the ethnic cleansing that made that state possible in the first place.

Did you participate in and film these two geographically distant struggles with this film project in mind? Or was it for two different projects originally? Did you meet in the process or beforehand? (Tell us more about the timeline of this diptyque film and the shooting)

The concept for the Native and the Refugee was always that of one project, the juxtaposition between the camp and the reservation was the nucleus. The cinematic aspect became our entry point into the spaces and struggles, our opportunity to meet people, visit, have conversations, and build relationships. By having a film and media project, by having a camera with us, it made it easier or possible to meet people in the first place, whereas just showing up wouldn’t have made much sense. The concept of creating a dialogue and communication between Palestine and indigenous territories in America helped us gain access to organizers on the reservations, who were initially skeptical. The Palestinian struggle is so globally known, having the opportunity to link these experiences is what enabled us to gain some trust.

We started in Pine Ridge in South Dakota, which is probably the most iconic reservation in the US: the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, the American Indian Movement’s 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, and the shootout between AIM members and the FBI in 1975, from which Leonard Peltier remains in prison. One of the first people we met in Pine Ridge, Olowan Martinez, invited us to come precisely because her mother visited Palestinian refugee camps in the late-1970s, in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War, as part of an American Indian Movement delegation. We went to Pine Ridge in late-2014, and that was when and how it all began. We made the short film We Love Being Lakota out of this first trip, and could then use that as an introduction to the other communities, helping frame our work in terms of the films we wanted to make, and the conversations we wanted to have. As we went to different reservations and refugee camps we made short films that we could show to the people we were going to be filming with. In this way a kind of feedback loop developed between the work we made, were making, and planned to make, informing what images and testimonies we were able to record as we moved along.

[We Love Being Lakota: https://vimeo.com/123021080 ]

How and why did the need arise to compare the two struggles, the two “peoples”, the two territories and the two oppressive states ?

Growing up in the United States, and New York City, there is probably more discussion and awareness of the Israel/Palestine conflict than there is about indigenous movements. We wanted to think about the processes and legacies of settler-colonialism, which people had used before to compare state formation in the United States and Israel, but we wanted to do so by having discussions about contemporary movements among Native Americans and Palestinians, and to do so specifically in refugee camps and on reservations. We felt like this framework could provide us with fresh ground to think through sovereignty and citizenship, and the movements to undo or reinvent what these concepts can mean today. It was also important for us to think through not just the hardships, but also the potentialities of these spaces and their exceptionality.

When people think about exceptionality, following Schmitt and Agamben, they think of it through the framework of a legal status, and they think of it in temporal terms. We wanted to take this concept and see how it could be expanded to include or describe a physical space that existed outside the normal legal machinery of political, economic and social recognition, legitimation, and inclusion. But we wanted to show that, despite the intense difficulty and tragedy of these spaces, that their exceptionality is imbued with potentiality. The reservations have long been spaces where Native peoples and communities have articulated, embodied, and fiercely defended modes of governance, relations to land, senses of community, language, and even perceptions of temporality outside of or in direct opposition to an American logic of individualism, extractivism, expansionism, etc.

As Paul Delaronde says in our film, “No one should ever refer to themselves as a nation, we are not, we are a people, Onkwe, that’s who we are. Canada is not a people, the United States is not a people. A nation is just a corporation.” The exceptionality of these spaces is forced upon the communities by the United States government, but it is also defended by the people themselves, in very different ways and for very different ends. With the Palestinians, the exceptionality of the refugee and space of the camp itself helped influence a revolutionary movement that was represented by groups like the PLO, PFLP, DFLP, who championed a logic in many ways outside the statism of Jordanian, Syrian, Lebanese or even Arab nationalisms. The exceptional non-citizen, non-state nature of the Palestinian movement allowed it to activate and stand for a revolutionary potential throughout the Middle East, making it a threat not only to Israel and the United States, but to the Arab regimes themselves.

Did you encounter distrust of your approach in general during the shootings? Specifically with the everyday camera use? Or on the contrary, did people immediately embrace the usefulness of a film? How did you gain trust?

It was precisely the camera, the films, our position as media makers that enabled us to enter these spaces at all. Prior to this project, we didn’t have any real relationships or contacts at any of the locations we were interested in, and when we began reaching out to people, it was only because of our capacity or potential to document and transmit their experiences and stories that we were invited in. It wasn’t as friends or militants or organizers, but as conveyors or transmitters of experience that we initially entered these spaces. So there was both a trust and responsibility attached to the access we were given. We tried to communicate clearly that we wanted to make the films the participants themselves wanted, or would or could make with our support, so we viewed each other as collaborators. We would send them rough cuts to ask for comments and feedback before we showed anyone else. We would ask them what do they want to talk about, or what do they want people to know or think about, what do they want to show of their lives and these places, and that’s what you see in the films.

After the completion of each short film we would start to screen it, we would put them online, so then others started to become aware of what we were doing. People liked the films and started to support us and the project. We were always welcomed back each time we visited, and people would open up more and more about their stories, revealing things that at first they were reluctant to.

[The History of the Camp: https://vimeo.com/147651593 ]

Militant use and political utility of images, here of archives and documentaries: how and why did you feel the urgency, the need to participate through cinematographic means to these struggles? It is not always easy, and a certain instrumental relationship to political struggles by filmmakers, is regularly criticized as potentially dangerous.

Usually documentary filmmaking is a one way street where documentarians represent a community to the outside world. In that process the struggle, even if not directly misrepresented, loses some representational agency and falls prey, at worst, to the spectacle of voyeurism. The so-called ‘outside world’ that filmmakers are documenting for, and transmitting images to, is usually imagined as a Western, white, middle class, cinema-going audience. That representation may be accurate or inaccurate, helpful or harmful, but it is still a primarily unidirectional process, where subjects are transmitting something out, rather than taking anything in or learning something new. With the short films that we made, we would not only show people from the camps and reservations works made in that specific site, but also films from other camps and other reservations. This process of transmission between communities in struggle, between the communities in the films themselves, was outside of the normal instrumentalizing relationship that can come to characterize a filmmaker’s approach to political struggles.

Another of the many potential traps within political filmmaking has to do with the actual content, in that certain subjects have been conditioned to say certain things in front of a camera. The Palestinians, for example, especially in the West Bank, are far more used to outside journalists coming in for just a day, shooting what they can, and leaving. So there we had to try to differentiate ourselves, to ask different questions, try to form different relationships, to get at different aspects of how they viewed their situation and struggle. Normally journalists and documentarians want to hear and see how difficult their lives are, how hard it is to live under Israeli occupation, which of course is always clear, but we really wanted to focus on what they thought, what was their analysis, vision, horizon, and that felt new – to really open up a space to think together, rather than just document hardship, or bear witness to their complaints. In both cases that specificity of interrogation was our means of inviting not only those in front of the camera, but also our audiences and ultimately ourselves as filmmakers, to actively think together in real time, rather than ritualistically document the typical sound-bytes and images to the same audiences with the usual results.

At the beginning of the film, there is a poetic and political immersion in both worlds, in the two territories with an assumed creative subjectivity – the music, the editing, from one continent to another in rhythm and from formal motives. At first I expected an experimental film that uses political struggles to propose a visual poem. How did you work on editing so that the correctness of your tone and form are politically coherent? What were the difficulties?

We decided for our feature film, Spaces of Exception, after producing around a dozen shorts, that we would present each space as a distinct, self-contained segment, using only footage we ourselves shot on location, that we would not intercut between places, and would present the overall work in an episodic structure: Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota; Balata and Dheisheh refugee camps in the West Bank; Akwesasne territory on the US/Canadian border; Bourj al Barajneh and Bourj al Shemali camps in Lebanon; and Navajo Nation in New Mexico/Arizona. We felt if we were to merely jump back and forth between reservations and camps the specificity of each site would be lost, there would be no distinction between the West Bank and Lebanon, or between Akwesasne and Pine Ridge, and for us this was not only profoundly inaccurate in terms of a sensible portrayal of these actual spaces, but almost amounted to a political and theoretical betrayal of our initial framework. But for the opening of the film we did want to use historical, archival footage, and blur between the two, so it wasn’t clear what or where or who you were looking at, in order to introduce the conceptual juxtaposition and exchange. In the film we never ourselves say, this is how these spaces or histories are similar, or this is how they are different, the hope was that the film would work politically as a kind of long form version of the Kuleshov experiment: to place two images together in sequence produces a third image that comes to exist in your head. By watching these segments consecutively in the context of the feature film a third reality comes to exist in your head, a reality that is not specifically the camp or the reservation but is informed by both. In that sense it is the relationship between the sequences themselves, rather than the images, where we think the cinematic experience of the film ultimately resides. This approach was probably informed by our work as curators and film programmers, where we would think of cinema as a physical experience that is constructed by the pairing of various different films or segments in succession with one another.

Then, once the film was finished, how was the reception of the film by the people filmed, or concerned in the front lines by these struggles? And how was it received by the colonial states, if the film circulated there?

As we were visiting and revisiting the spaces we focused on we were regularly in communication with the people, we would screen our cuts, do talks and presentations, have discussions about our research, the concepts we were using, listen to their feedback, comments, suggestions, to hear what people thought not just about their own portrayals but how we were depicting these other places and people as well. We also worked with a number of different photographers and editors, including other Palestinian and indigenous artists, so they were part of the conversations as well. Thankfully much of the feedback we received was rarely along the lines of this was good, or this was bad – it usually took the form of some sort of active intervention. “You could have have included such and such in the film, or added such and such struggle to your comparison, or shoot in such and such place, or spoke to so and so person” etc etc. The film is always a potentiality, a work in progress, which we’re comfortable with.

When the Standing Rock movement started in the summer of 2016, a number of indigenous organizers were inviting us to come out to help make films on the movement, and do workshops about filmmaking and media strategies. Standing Rock and Pine Ridge are both Lakota reservations, and some of the activists and organizers we had previously met and formed a relationship with at Pine Ridge ultimately ended up on the front lines at Standing Rock. We worked closely with the West Coast Women Warriors Media Cooperative, one of whose organizers we met at an event we did in Vancouver. They were based in and around the Red Warrior Camp, and wanted to start conversations about the role of video in the movement. Though part of the conceit of The Native and the Refugee was to work with spaces and communities rather than attempting to document events happening in real time, Standing Rock forced us to straddle the line between a kind of timeless cinema on the one hand, and an interventionist video that circulates as events are unfolding on the other. We produced two short films on Standing Rock, All My Relations and Indian Winter, both in collaboration with Vanessa Teran, an Ecuadorian artist. With the immediacy of social media images are constantly proliferating and then quickly disappearing, but cinema offers an opportunity to create a narrative and mood, combine testimony and ambiance–it’s something you can refer to now or three years later to reimmerse yourself in that place, that feeling of being there.

[All My Relations: https://vimeo.com/193125500 ]

It’s hard to say how a film is received by a state, especially ones like the United States and Israel, which in their neo or post-colonial modes pride themselves on being spaces of free expression and open dialogue. We can share that last March we were prevented from entering Israel by its Department of Interior. We had hoped to screen the film in Jerusalem, but weren’t allowed in to do so, despite the Trump administration officially recognizing it as the capital of Israel and new location of the American embassy. Borders, both between the US and Canada, and of course in the Middle East, have been our persistent enemy throughout the filmmaking process, but the reception to the work by people themselves has been positive. For us the best reactions are not whether people like or don’t like the films, but when people treat the work as the beginning of a discussion, a discussion we have been having and hosting for five years now. We hope with the feature film Spaces of Exception those discussions will continue to take place.

Spaces of Exception at Anthology Film Archives: http://anthologyfilmarchives.org/film_screenings/calendar?view=list&month=10&year=2023#showing-56703

The Native and the Refugee Short Film Program: http://anthologyfilmarchives.org/film_screenings/calendar?view=list&month=10&year=2023#showing-56708

Acts of Defiance: http://anthologyfilmarchives.org/film_screenings/calendar?view=list&month=10&year=2023#showing-56711

Matt Peterson is an organizer at Woodbine, an experimental space in New York City. He previously directed the documentary feature Scenes from a Revolt Sustained (2014), and co-edited the books In the Name of the People (2018) and The Reservoir (2022).

Malek Rasamny is a documentary filmmaker, researcher and writer. His work has been featured in publications including The New Inquiry, Lundi Matin and Newlines Magazine. He is currently working on a doctoral research project at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS) concerning the social phenomenon of reincarnation within the Druze community of Lebanon.