By Bob Podurgiel

Gazette

Carnegie’s 3rd Street is a charming place to take a stroll. Two art galleries – the 3rd Street Gallery, featuring the artwork of Philip Salvato, and Double Dog Studios, highlighting the work of artist Dave Klug – welcome visitors to explore the visual arts, with musical concerts, play readings, and dance performances occurring there regularly.

Across from the Gallery, sits the imposing red brick edifice of the former St. Lukes Church, its two towers topped by Celtic crosses where a large red-tailed hawk sometimes perches, scanning the streets below for unwary pigeons or squirrels.

A heating and cooling company near Double Dog Studios features a robot made from sheet metal ductwork in its window. The metal robot is a quirky signature of the street, reminiscent of the Tin Man from the “Wizard of Oz.” There’s also a laundromat, a convenience store, where you can buy just about anything you need in a pinch, and a funeral home, all a short distance from the Glendale Bridge linking 3rd Street with Carothers Avenue in Scott Township.

Nothing on the idyllic street hints at the epic clash that took place here on Aug. 25, 1923 between thousands of white-robed Ku Klux Klansmen and Carnegie citizens, mostly Irish Catholics, who fought the Klan that night to stop them from marching in Carnegie and, as rumor had it, burning a cross at St. Lukes Roman Catholic Church.

The events leading up to the fighting on the streets of Carnegie began on a hill overlooking the town and the entire Chartiers Valley.

At the behest of Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans, a dentist from Dallas, more than 10,000 active Klansmen from Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio and Pennsylvania gathered for a cross burning and to initiate 1,000 new members into the racist group.

The rally was part of an effort by Evans, with the full support of the Grand Dragon, D.C. Stephenson, to expand Klan recruitment into Western Pennsylvania.

The Klan’s push into Pennsylvania began with marches in New Wilmington, Punxsutawney, and New Castle, but the biggest, and it turns out, the most violent march, would occur in Carnegie.

After burning a 50-foot high cross and gathering in a circle with lit torches as a grim welcome to the new members, Klan organizers planned to march through the streets of nearby Carnegie, the small coal mining, steel, and railroad town filled with recent immigrants.

Klansmen in America were alarmed at the waves of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe coming to America after the first world war. The Klan in the 1920s also had a bitter enemy in the Irish Catholics.

The Klan believed that America was, and should always remain, a country ruled by white men, mainly Protestants from Northern Europe and the British Isles. There was no place in their concept of America for Blacks, Jews, Irish Catholics, Italians or Eastern Europeans, all of whom they labeled as Papists intent on dominating America.

As the Klansmen, carrying torches, and dressed in white robes with hoods covering their faces approached the Glendale Bridge linking Carothers Avenue in Scott Township with Carnegie’s 3rd Street, they were met by an angry crowd of Carnegie citizens intent on blocking the Klan from crossing the bridge into their home.

Despite the best efforts of John J. Dillon, assistant deputy sheriff of Allegheny County, who pleaded with the Klan to give up their plans to march in Carnegie, fighting soon broke out between the two groups.

Klansmen surged across the bridge, pushing the citizens back onto 3rd Street. Barrages of bricks, stones, and pieces of metal rained down on the Klansmen, who retaliated by beating residents with fists and clubs. Fighting continued all along 3rd Street that night across three blocks to the intersection of 3rd and West Main Street, where Klansman Thomas Rankin Abbott from Washington County was shot and killed.

Newspaper accounts of the riot by the “Pittsburgh Gazette Times” and the “Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph” described hundreds of Klansmen and Carnegie residents wounded in the fighting, with volleys of gunfire exchanged between the combatants, resulting in one Carnegie man shot twice in the back and once in the leg. Injured Klansmen included one shot in the abdomen and one in the head. Hundreds of other Klansmen and residents suffered injuries ranging from broken bones to fractured skulls.

Abbott was the sole fatality in the riot, but after he was killed, Klansmen retreated back to the Glendale Bridge and began a weary trek back to their rallying point on the hill overlooking Carnegie before fading into the night.

“The Pittsburgh Gazette Times” reported on the Klan’s retreat.

“Many men, dusty, torn, and apparently wary, some with unattended wounds and lacerations, and bruises, were seen in Pittsburgh restaurants and passing through the city in automobiles,” according to one article.

Allegheny County detectives believed a Carnegie funeral home director, Patrick “Paddy” McDermott, was responsible for Abbott’s murder, but a coroner’s inquest jury found there wasn’t enough evidence to charge McDermott with murder. The case is still unsolved today.

While the Klan suffered a defeat that night in Carnegie, they had their eyes on a bigger prize in Washington D.C. At the urging of Klansmen from around the county, Congress passed a stringent overhaul of the nation’s immigration policy in 1924, drafting a law that remained on the books for 41 years.

One of the more tragic consequences of the law was that it reduced immigration to a mere trickle from countries with large populations of Blacks, Catholics, and Jews.

When the Nazis rose to power in Europe, desperate refugees, many of them Jews who would later die in Nazi death camps, were unable to enter the United States.

Today issues of immigration, and who holds political power in the states and in Washington D.C., continue to roil the country. Although the Klan achieved a good amount of political power, the 1920s era-Klan failed to achieve its ultimate goal of creating a country open only to white Protestants of Northern European and British descent.

The jury is still out on whether the ideas espoused by the Klan will finally prevail in America’s current toxic political climate where hatred and fascist leanings are once again on the rise.

Interview with Bill Campbell

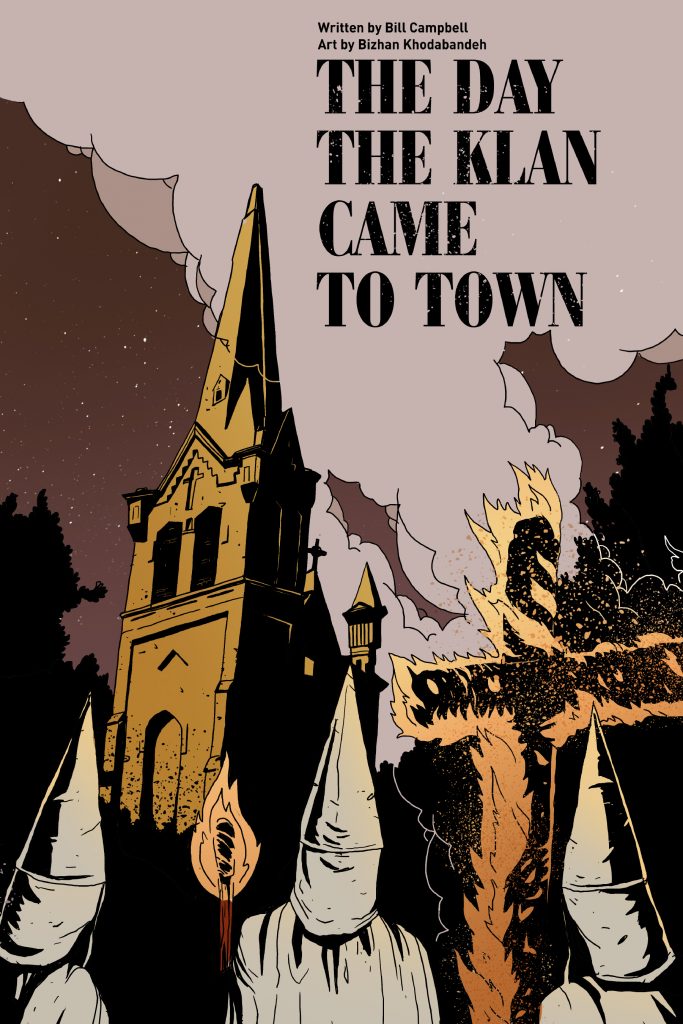

Bill Campbell wrote the 2021 graphic novel, “The Day the Klan Came to Town,” about a 1923 incident in Carnegie when the immigrant community came together to stop the Ku Klux Klan from overrunning their home. Campbell is participating in a panel discussion about the historical incident on Aug. 15 from 7 – 8:30 p.m. at the Carnegie Carnegie Free Library and Music Hall.

Campbell

Campbell has authored at least half a dozen books, according to his biography including Sunshine Patriots and Koontown Killing Kaper and is a prolific editor. He’s compiled many anthologies, including an anthology with Edward Austin Hallen entitled: “Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond.”

Campbell won a Glyph Pioneer/Lifetime Achievement Award for coediting: “Stories for Chip: A Tribute to Samuel R. Delany; APB: Artists against Police Brutality.”

The author lives in Washington, DC, where he runs Rosarium Publishing, and he answered our questions via email. His responses were edited for grammar and style.

1. Is the Klan march on Carnegie something you grew up knowing about, or something you learned about later?

To be honest, I hadn’t heard about it until 2019. I was at my mother’s house for Easter, and my brother and I were talking about things we were never told about Pittsburgh growing up: the massive coal fire in the 1800s, the poison gas in Donora … and then my brother said, “The Klan riot in Carnegie.” And I was, like, “What the hell are you talking about?!”

2. Why did you choose to use a fictionalized Italian immigrant as your central character?

It was totally by accident. A couple months after my brother told me about the Klan riot, I was driving back home to DC from Toronto. I stay over my mom’s for the night, so I have to get off of 79 and drive around Carnegie on 279. As I was doing that that night, the main character, Primo Salerno, popped into my head, drawn in Bizhan [Khodabandeh’s] style. At that moment, I figured I had to write the book.

3. As you did your research, what surprised you the most?

I guess the biggest surprise/non-surprise is how white supremacy’s language hardly ever changes–probably because it’s the language of fear. Today it is called “the great replacement theory.” Back then it was called “race suicide.” Today they’re talking about how Brown and Jewish people will wipe out the white race. A hundred years ago it was the same groups, but it also included southern and eastern Europeans.

4. What made you want to bring a story from the past to life?

America, just like any other country, whitewashes (pun intended) its own history basically to the point of myth. I’m not saying there aren’t truths in the histories that we’re taught, but there are way too many facts left out. (As an example, many say the Founding Fathers were “men of their time” in regards to slavery. Yet, Thomas Jefferson actually condemns slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence. So, even he thought it was wrong–or at least paid lip service to the idea.) The problem is that these myths not only shape thought; they shape policies, they can start wars (after all, white supremacy is a myth borne out of slavery and has given us everything from countless forms of discrimination to World War II). They’re ultimately harmful, even destructive. Besides, America’s history is insanely complex and incredibly interesting. So, for me, bringing such stories to light is fascinating to me, and I hope it helps to dismantle some of these myths.

5. Some of your other work deals with Afro-futurism; does that movement relate to your historical work and if so, in what way?

To me, being human is to be in constant conversation with the past, present, and future. So, as a writer, when I’m creating I am often looking at the past and present through the lens of my own imagined future and vice versa or some weird sort of remix of the three. Because history is an obsession of mine, anything I write, no matter the genre, references historical events. So, maybe, being forced to think about it, most of my work would be creative interpretation, re-interpretation, and projection for a better future.

Carnegie library commemorates 1923 fight to eject KKK marchers

With 2023 marking the 100th anniversary of the Ku Klux Klan riot in Carnegie, the town will commemorate the event with two programs at the Andrew Carnegie Free Library and Music Hall.

The programming will explore why on a hot August night in 1923 the town fought the Klan, preventing the Invisible Empire from marching in the streets of Carnegie.

In the first event, set for 7 p.m. on Tuesday, Aug.15 a book group, focusing on diversity and social justice issues, will discuss the graphic novel, “The Day the Klan Came to Town.” The novel was published in 2021 and written by Bill Campbell and illustrated by Bizhan Khodabandeh.

The graphic novel follows the experiences of a fictional character, an Italian-American immigrant who experiences anti-immigrant prejudice and who fights against the Klan during the riot.

The book group discussion will be followed up by a full-panel discussion at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, Aug. 23 at the library. The panel will include members of the Carnegie Historical Society and the Heinz History Center, as well as, Bill Campbell, graphic novel author, and Bizhan Khodabandeh, illustrator.

Part of this event will explore how the events that occurred in Carnegie are still relevant today.

The Andrew Carnegie Free Library & Music Hall is located at 300 Beechwood Ave., Carnegie. For more information on these events, carnegiecarnegie.org.