by Mark Scroggins

SFRA Review

Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre’s essay collection Dangerous Visions and New Worlds, as its title indicates, focuses in the first case on the 1960s ‘New Wave’ in science fiction, a movement whose key moments include Michael Moorcock’s editorship of New Worlds (from 1964) and Harlan Ellison’s 1967 anthology Dangerous Visions. The collection’s thirty-five-year subtitle, however, signals its larger scope and ambitions: an overview of what the New Wave made possible—an opening up of the genre to a wide variety of new voices, new thematic concerns, new formal constructions. Histories of SF invariably devote a chapter to the New Wave, describing how its writers, as part of larger counter-cultural movements in the postwar decades, reacted against an overwhelmingly white, male ‘Golden Age’ genre that avoided psychologism, elided sexuality, and prized technological and scientific extrapolation over social exploration. But they tend to read the New Wave as part of a dialectical back-and-forth within the genre, a temporary shift in priorities which would be absorbed and transcended in the following decades. Dangerous Visions and New Worlds implicitly asserts that contemporary SF— perhaps the most multifarious, diverse, and socially and politically engaged of popular cultural forms—was not just made possible by, but is the New Wave, a tsunami which never receded, but continues to buoy us up.

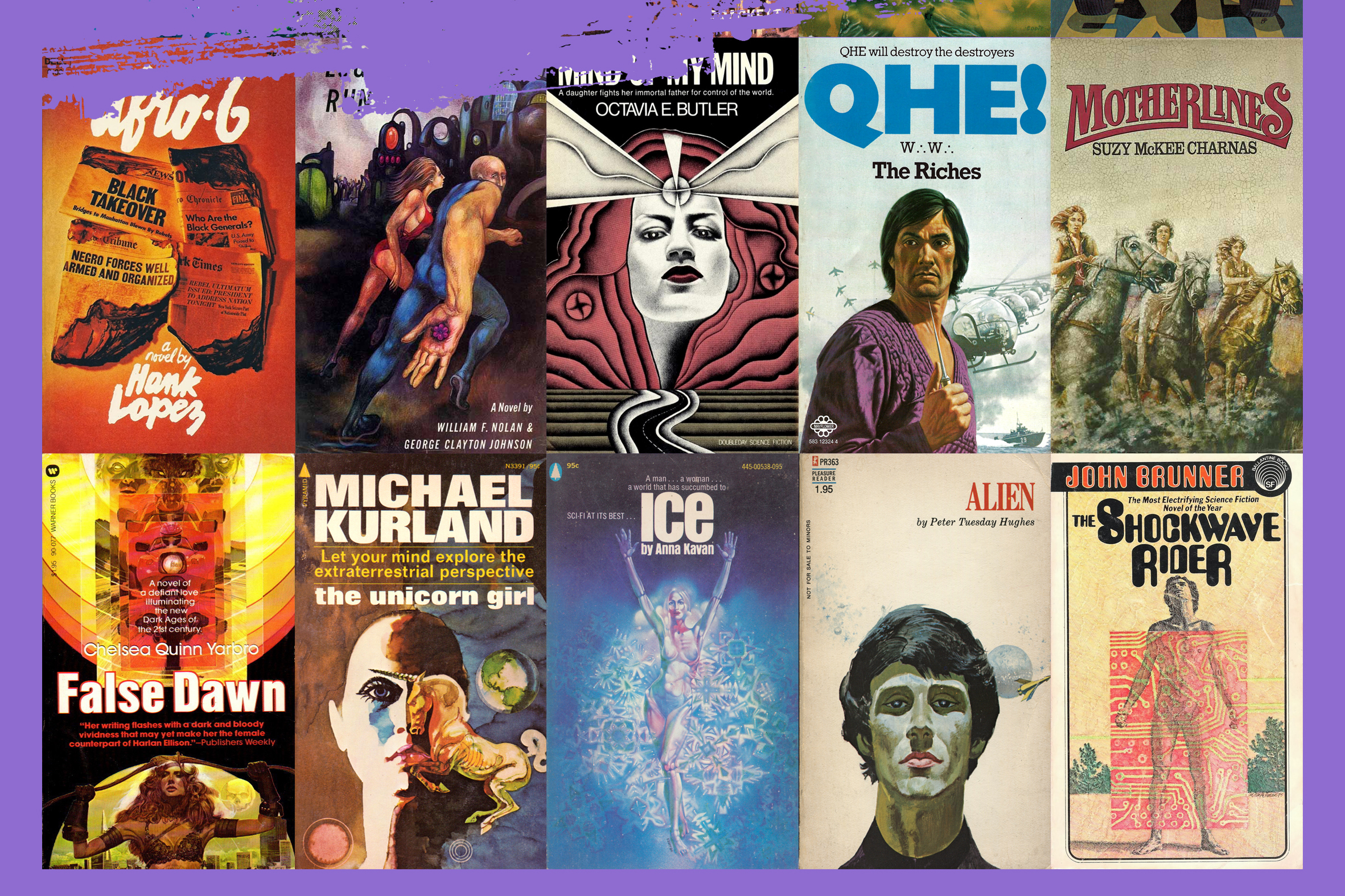

Sumptuously illustrated with photographs of authors, book covers, and other ephemera, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds appears at first glance more like a coffee table book than a serious overview of the genre. It contains almost forty items, which toggle between two- or three-page capsule presentations and full-length, deeply developed essays. The capsule presentations (sidebars?) tend to be brief thematic summaries or short bibliographic notes: nuclear war in SF, drugs in SF, revolution and rebellion in SF; the publishing history of New Worlds, Doctor Who novelizations, The Women’s Press and SF; and so forth.

The full-length essays—which, alas, vary widely in quality—cover an unexpected variety of topics, from the fairly canonical (J. G. Ballard’s SF work, Alice Sheldon/James Tiptree Jr., Philip K. Dick, Octavia Butler), to the relatively obscure (Hank Lopez’s Afro-6 [1969], gay SF novels of the 1970s, Denis Jackson’s The Black Commandos [2013]), to the pleasantly quirky: one doesn’t expect to find an essay on R. A. Lafferty in such a volume, but Nick Mamatas’s “God Does, Perhaps? The Unlikely New Wave SF of R. A. Lafferty” is welcome reading.

Nicholas Tredell’s “The Energy Exhibit: Radical Science Fiction in the 1960s” offers an excellent distillation of what was new about Moorcock’s New Worlds, as well as some good examinations of representative books by Brian W. Aldiss, Norman Spinrad, and Moorcock himself. In “On Earth the Air Is Free: The Feminist Science Fiction of Judith Merril,” Kat Clay provides a welcome reminder of what was really ground-breaking about the work of the anthologist and writer who by some accounts coined the term “New Wave.” Rebecca Baumann’s “Speculative Fuckbooks: The Brief Life of Essex House, 1968-1969” is a straightforward history of this SF-porno publisher, whose rather high-minded, even ‘literary’ project was undermined by its very conditions of possibility: the 1960s court cases which made pornographic fiction legal in the US resulted in a flood of easily accessible erotica, a saturated marketplace in which Essex House could not survive.

This is not for the most part an academic collection, though a few of its essays were previously published in scholarly journals. It’s good to re-read Rob Latham’s lively “Sextrapolation in New Wave Science Fiction”; others of the “academic” chapters, unfortunately, have the stuffy atmosphere of dissertation chapters. There’s a wonderful breadth and variety to the materials covered in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds, but at times the book feels just plain scattered, both in its subject matter and in the approaches its authors adopt. While essays on the Strugatsky brothers (a career overview) or Le Guin and Heinlein (comparing The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress [1966] and The Dispossessed [1974]) are informative, it seems something of a stretch to include them among the other materials here assembled.

One shouldn’t go to Dangerous Visions and New Worlds expecting something like a Cambridge Companion to New Wave SF; it’s just not that sort of book. But one would have welcomed, if not a full bibliography of materials related to the subject, at least some suggestions for further reading, and perhaps a timeline of important events and publications. And one would have welcomed a greater degree of editorial uniformity among the pieces (including some draconian cuts to some of the more wordy essays). One of the volume’s great joys, however, is its plethora of reproductions of paperback covers—literally hundreds of them, ranging from ‘60s and ‘70s updates of Golden Age pulp motifs to the mind-blowing abstractions and surreal scenes that make SF cover illustration one of the most consistently stimulating subgenres of visual art in the last third of the twentieth century.

Mark Scroggins is a widely published poet, biographer, and critic on modern and contemporary poetry. In the Fantasy/SF field, he has published a monograph, Michael Moorcock: Fiction, Fantasy and the World’s Pain (2015), and essays and reviews in Foundation, JFA, Fafnir, and the NYRSF.