By Spencer Beswick

Institute for Anarchist Studies

July 4, 2023

Anti-fascism exploded into the public spotlight after Donald Trump’s electoral victory in 2016. Spectacular street battles between fascists and anti-fascists in the heart of liberal cities including Berkeley and Portland led to antifa becoming a widely discussed phenomenon and a new bogeyman of the right. Yet despite their meteoric rise to popular consciousness in the past decade, neither fascism nor anti-fascism came out of nowhere. In the United States, fascists continued to mobilize after World War II in the American Nazi Party, the Ku Klux Klan, the Christian Far Right, and beyond. In the 1980s, a significant segment of the fascist and white power movements embraced violent revolutionary struggle against what they saw as a decadent Jewish-controlled government that had betrayed the white race.

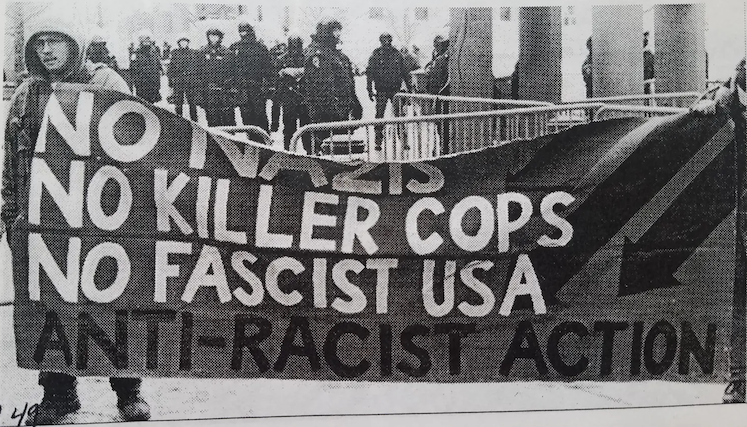

In turn, anti-fascists have long sought to disrupt fascist organizing, in part by drawing on the experience of past generations who fought the rise of fascism in Europe. Contemporary US antifa dates back to the late 1980s when anarchists, skinheads, and punks in Anti-Racist Action (ARA) developed a revitalized strategy of militant anti-fascism to combat the growing power of the Far Right. This history has received new attention since Trump’s election, and Anti-Racist Action was even featured in a recent PBS Frontline documentary. Despite this renewed attention, the foundational role that revolutionary anarchism played in the development of ARA has thus far gone under-examined in mainstream accounts, obscuring its historical lessons.

Today, a sizeable segment of the Left has rallied to defend liberal democracy and mainstream institutions from the threat of fascism. This has ceded ground to the Far Right, who are attempting—with some success—to position themselves as the only real alternative to the liberal order. Anti-Racist Action offers a different model for anti-fascist struggle that maintains the Left’s autonomy from the state and liberal institutions.

Anti-Racist Action was the premier anti-fascist organization in the late twentieth century US. It grew out of a youth anti-racist skinhead crew in Minneapolis called the Baldies, which founded ARA in 1987 in an effort to expand its organizational capacity. ARA grew quickly across the country and its members became known for their willingness to physically engage fascists in punk spaces, on the streets, and beyond. Although they were best known for physical confrontation, they also conducted extensive campaigns to publicly expose fascists. ARA was guided by three primary points of unity. First, “we go where they go”: anywhere fascists attempted to organize, ARA would confront and disrupt them. Second, “we don’t rely on the cops or the courts to do our work for us”: they used direct action and self-organization to confront fascists, rather than hoping for intervention from the police or the state. Third, they upheld “non-sectarian defense of other anti-fascists”: they were united in tactical opposition to fascism and white supremacy, rather than divided by rigid ideological lines. In 1997, the ARA network voted to add a fourth point of unity: “we support abortion rights and reproductive freedom.” Women pushed ARA to recognize the fascist nature of the Far Right anti-abortion movement and dedicate their energy to confronting it. In a further revision, and despite their commitment to ideological pluralism, ARA ended the points of unity with a new political call to action: “We want a free classless society. WE INTEND TO WIN!”1 Yet many accounts of ARA, with notable exceptions like the anarchist historian Mark Bray’s Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook and recent books from PM Press including We Go Where They Go: The Story of Anti-Racist Action and It Did Happen Here: An Antifascist People’s History, have generally downplayed this anarcho-communist vision of a “free classless society.”

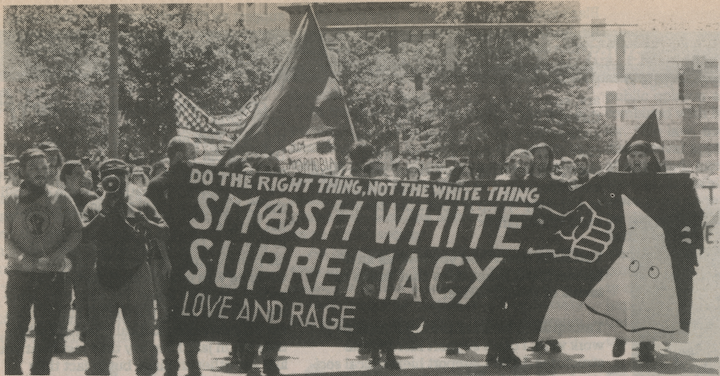

Efforts to emphasize the broad-based character of ARA have perhaps made it more appealing to popular audiences but have had the unfortunate consequence of minimizing its revolutionary politics. Downplaying the centrality of anarchism to ARA impoverishes our understanding of the organization and, more broadly, the history and practice of militant anti-fascism. As Mark Bray puts it, “anti-fascism is an illiberal politics of social revolutionism applied to fight the Far Right.”2Although ARA never adopted a formal political line, anarchist ideology and organizational principles predominated within it. A small number of members of the most significant anarchist organization of this period, the Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation (1989-98)—particularly Kieran Frazier—played an outsized role. Their anarchist politics and organizational experience shaped ARA from its beginning. Most accounts of ARA do acknowledge the role of anarchist politics, and at least mention that Love and Rage played an important part.3

Centering the contributions of anarchism in our historical analysis reveals how ARA fought fascists but also provided a radical alternative to the Far Right’s war against the state. Anarchists in ARA worked with unorthodox Marxists to develop the “three way fight” analysis of fascism, which holds that fascism is not simply a tool of ruling class capitalist reaction, but rather poses an autonomous, often revolutionary threat to the capitalist state. Thus, the Left must engage in a three way fight with both the capitalist state and the fascist movement simultaneously—and must ultimately present a revolutionary alternative to both. For Love and Rage and Anti-Racist Action, anti-fascism could not simply mean the defense of the liberal democratic state against fascism, but rather necessitated its revolutionary overthrow and the construction of a libertarian socialist society.

Part One: Fascism’s Revolutionary Turn and the Three Way Fight Analysis

- Fascists Declare War

During the 1980s, leading elements of the fascist and white power movements declared revolutionary war on the US government. At the same time that Reagan led a conservative counterrevolution that won state power for the New Right, the fascist Far Right embraced anti-systemic armed struggle. Instead of using violence to uphold the status quo’s racial order as the KKK had traditionally done, neo-Nazis and Klansmen united to fight for a “white revolution” against what they deemed the “Zionist Occupied Government.”4 As anti-fascist historian Matthew Lyons puts it, fascists in this era became “system-disloyal” rather than “system-loyal.”5 Many were inspired by the vision of revolutionary struggle laid out by the leader of the National Alliance, William Luther Pierce, in his novel The Turner Diaries. In the novel, which quickly became an underground classic, a Neo-Nazi organization called The Order formed the vanguard of the white race and engaged in terrorist activity in order to overthrow the state (and the “Jewish” bourgeoisie) and forge a new white nation—having murdered all people of color at home and worldwide. The novel inspired a real-life group called The Order which engaged in violent activity including armed robberies and the murder of the liberal Jewish talk show host Alan Berg in 1984.

Fascists offered a radical program to white people who felt betrayed by the government’s grudging acceptance of Black civil rights and its defeat by communists in Vietnam. They followed the general form of Robert Paxton’s classic definition of fascism, but with more focus on individual and small group terrorism—as William Pierce advocated in his second novel Hunter—rather than mass activity.

Fascism may be defined as a form of political behavior marked by obsessive preoccupation with community decline, humiliation, or victimhood and by compensatory cults of unity, energy, and purity, in which a mass-based party of committed nationalist militants, working in uneasy but effective collaboration with traditional elites, abandons democratic liberties and pursues with redemptive violence and without ethical or legal restraints goals of internal cleansing and external expansion.6

Economic disruption combined with the racial challenge of decolonization and attendant mass immigration created an explosive situation. The state was seen as either powerless to change any of this or indeed guilty of facilitating it. Rather than blaming capitalism, fascists denounced the “Jewish” bourgeoisie that they believed controlled the government and were attempting to destroy the white race. Given this, a growing number of fascists and white power activists saw no future in the current order. They began propagating the Fourteen Words, a slogan coined in 1984 by David Lane (himself a founder of The Order): “we must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.” The only way to secure this future was to use revolutionary violence to purify society.

Importantly for this piece, many disaffected young white people turned towards punk subculture. Many punks gravitated towards anarchist or other leftist politics, but a significant minority turned to fascism and white power—particularly a subset of Neo-Nazi skinheads. Some Neo-Nazis and Klansmen of an older generation, most notably Tom Metzger of the White Aryan Resistance (WAR), attempted to harness this force, recruiting followers through punk and encouraging them towards violence. They organized with the KKK, Aryan Nations, and other white supremacists and fascists to build a “white revolution.” As documented in the recent podcast-turned-book It Did Happen Here: An Antifascist People’s History, the murder of an Ethiopian immigrant named Mulugeta Seraw in Portland in 1988 by a group associated with White Aryan Resistance signaled a clear escalation. But a new generation of anti-fascists rose up to meet them—often with masked faces and baseball bats in hand.

- Understanding Fascism and Anti-Fascism: The Three Way Fight

Anti-fascists revised their analysis of fascism in order to confront its revolutionary turn. Anarchists and unorthodox Marxists in Anti-Racist Action developed an analysis of fascism and anti-fascism that became known as the “three way fight.” They framed it in opposition to the predominant Stalinist and Trotskyist theories of fascism. The old Stalinist/Comintern analysis from the 1920s-30s argued that fascism was a reactionary capitalist strategy to preserve its power in the face of revolutionary challenges. Any mass support for it came from false consciousness rather than from some intrinsic working-class orientation towards fascism. This tendency concentrated on opposing capitalism while essentially ignoring fascism and downplaying its specific threat, at one point even operating in Germany under the slogan of “first Hitler then us.” Yet when the Communist revolution failed to materialize, Stalinists reversed course and endorsed a broad popular front against fascism in the mid-1930s.7 Trotskyists disagreed with this analysis and its attendant political line. In “Fascism: What It Is and How to Fight It,” Trotsky argued that the class base of fascism was not the capitalist class but rather the petty bourgeoisie, who had no real ideology of their own. If there was a strong working class movement, the middle class would be pulled towards its leadership. In the absence of this, the middle class would swing towards reaction and common cause with the most retrograde wing of capital. In this analysis, written with the historical knowledge of fascism’s rise in Italy and Germany, fascism was a very real threat with a middle class social base that could not simply be reduced to a capitalist plot. The solution was to build the proletarian movement—including by arming anti-fascist workers’ committees to fight fascist street gangs—and build a united front of Left and proletarian parties (distinguished from a popular front that would include liberal/bourgeois forces).

The difference between Trotskyist and Stalinist analyses of fascism and anti-fascism helps explain the much larger presence of Trotskyists than other Marxist-Leninists in ARA. Yet whatever their strengths, neither of these frameworks acknowledged the central role of anti-Semitism or of race more broadly in constituting fascist politics. In the United States, there was no way to understand fascism without rooting it firmly in white supremacy—especially anti-Blackness, but also anti-Semitism and anti-immigrant sentiment. This is why the activists who formed ARA decided to call themselves Anti-Racist Action rather than Anti-Fascist Action like their European counterparts: they felt that the former would be more salient to the US situation. But the revision of the traditional Marxist analyses of fascism went beyond race, and beyond the differences between European and US fascism.

The most important theoretical innovation to come out of the ARA milieu was the framing of a “three way fight” between the Left, capitalism and the state, and the Fascist Right. This analysis insists that fascism cannot be reduced to capitalist reaction but must be understood as its own autonomous radical tradition—including a very real thread of anti-capitalism that goes beyond vulgar anti-Semitism. This analysis came from a confluence of anarchists and unorthodox Marxists. The latter included people like Don Hamerquist, who had been involved in the Sojourner Truth Organization, and the Maoist Third Worldist J. Sakai, best known for writing Settlers: The Mythology of the White Proletariat. Their meeting point and common point of reference, however, was ARA.

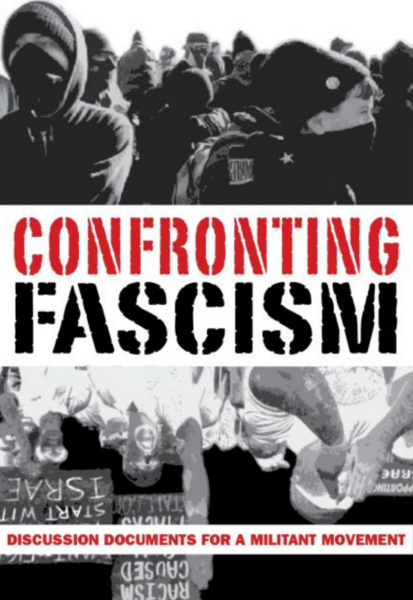

Three way fight politics were explicitly articulated in a collection called Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement, published in 2002. The collection is centered around an essay by Don Hamerquist called “Fascism & Antifascism.” Hamerquist argues that, rather than coming “from above” or supported by the capitalist class as a whole, “the emerging fascist movement for which we must prepare, will be rooted in populist nationalist anti-capitalism and will have an intransigent hostility to various state and supra-state institutions.”8 This means that “the essence of anti-fascist organizing must be the development of a left bloc that can successfully compete with such fascists, presenting a revolutionary option that confronts both fascism and capitalism in the realm of ideas and on the street.”9 The danger is that, as in the earlier popular front period, much of the Left may throw its support behind “liberal democratic” anti-fascism—i.e., the present capitalist order—and thus cease to present an alternative from the Left. If this were the case, the only “radical” alternative to capitalist democracy would come from the fascist, racist right.

Militant anti-fascists have continued to develop this analysis over the past two decades. The Three Way Fight blog (which includes former members of ARA) explains why they oppose both liberal anti-fascism and traditional Marxist anti-fascism: “Unlike liberal anti-fascists,” they maintain, “we believe that ‘defending democracy’ is an illusion, as long as that ‘democracy’ is based on a socio-economic order that exploits and oppresses human beings.”10 Therefore, anti-fascists must be anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist. But what really distinguishes the three way fight analysis from other anti-fascist currents is that they recognize the relative autonomy and anti-systemic political character of the fascist movement:

unlike many on the revolutionary left, we believe that fascists and other far rightists aren’t simply tools of the ruling class. They can also form an autonomous political force that clashes with the established order in real ways, or even seeks to overthrow global capitalism and replace it with a radically different oppressive system. We believe the greatest threat from fascism in this period is its ability to exploit popular grievances and its potential to rally mass support away from any liberatory anti-capitalist vision. Leftists need to confront both the established capitalist order and an insurgent or even revolutionary right, while recognizing that these opponents are also in conflict with each other. The phrase “three way fight” is short hand for this idea.11

This analysis has sweeping implications, including for our own moment as we confront a global revival of fascism. We will return to its implications in the conclusion. For now, we turn to consider how anti-fascists organized in response to the fascist resurgence of the 1980s. Even before the explicit theorization of the three way fight, Anti-Racist Action sought to defeat fascists in the streets while offering a revolutionary alternative to capitalism and the state. Anarchists played a key role in defining and maintaining this radical position within ARA.

Part Two: Anarchism and the Birth of Anti-Racist Action in Minneapolis

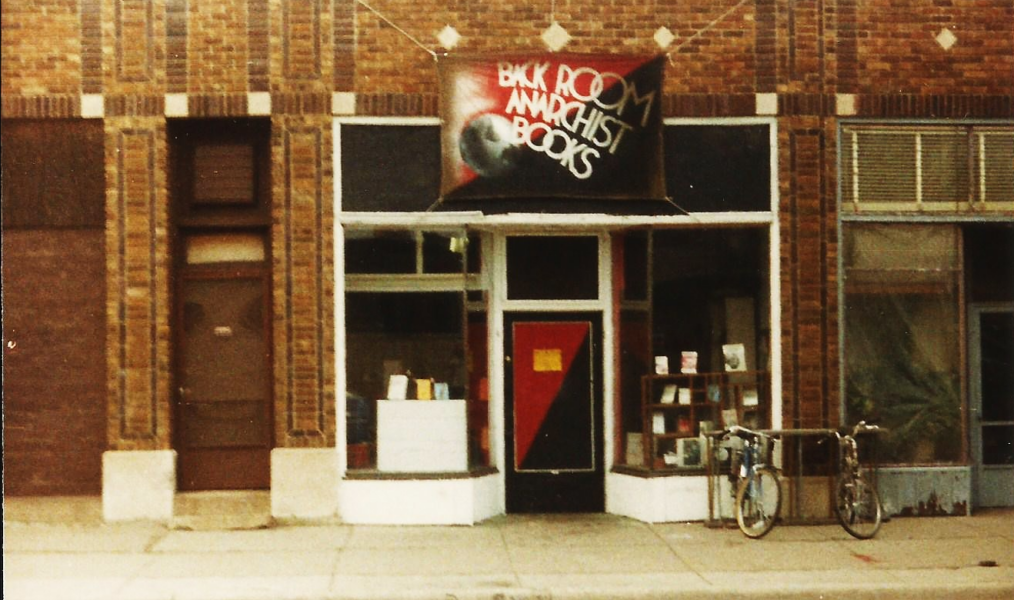

Kieran Frazier, one of the key founders of Anti-Racist Action, was raised as a red diaper baby with parents in the Communist Party. He discovered anarchism as a fifteen-year-old, when he was still a member of the Youth Communist League. He encountered it via Back Room Anarchist Books when he sought their co-sponsorship for a benefit concert that he was organizing for the South African ANC. Back Room was an anarchist bookstore run by a small collective of young anarchists committed to spreading propaganda and aiding radical struggles in the Twin Cities. At the bookstore Kieran met Chris Day, who was the primary force behind the Minneapolis anarchist scene. Their meeting launched a close friendship and political partnership that significantly shaped the development of the continental anarchist movement for over a decade. Chris challenged Kieran’s communist politics in part by forcing him to reckon with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Kieran, who is now a middle-aged anarchist and the shop steward of a union, remembers as a fifteen-year-old “actually laying in bed thinking, I’m going to have to decide, I’m going to have to either be with the Russians on this [chuckles], or totally against what the Russians are doing. There’s no middle ground to have.”12 The conversation with Chris and the night of reflection set Kieran down a new path. He soon started volunteering at Back Room Anarchist Books, where he found a political home in anarchism and a social home in the youth punk milieu.

Back Room played a central role in the formation and political evolution of the Baldies and Anti-Racist Action. Infoshops and anarchist bookstores like Back Room played a key role in distributing information in the pre-internet days. The ragtag collective that ran the store was plugged into national and international radical networks. It was through the Back Room that the Baldies first discovered anarchist publications from Europe, including news from the West German autonomous movement. Perhaps most important was the Class War newspaper from Britain, which provided accounts of how anti-racist skinheads were organizing to fight the National Front. In addition to its range of cheap anarchist books and zines, the bookstore hosted meetings and social events. The bookstore also provided models for effective forms of organization. Rather than just drinking beer and fighting Nazis, people like Kieran had experience with what it meant to organize, including basic things like facilitating effective meetings.13 The Baldies and ARA used the infrastructure provided by Back Room to develop their politics and connect with international networks of anti-fascist and anti-racist punks.

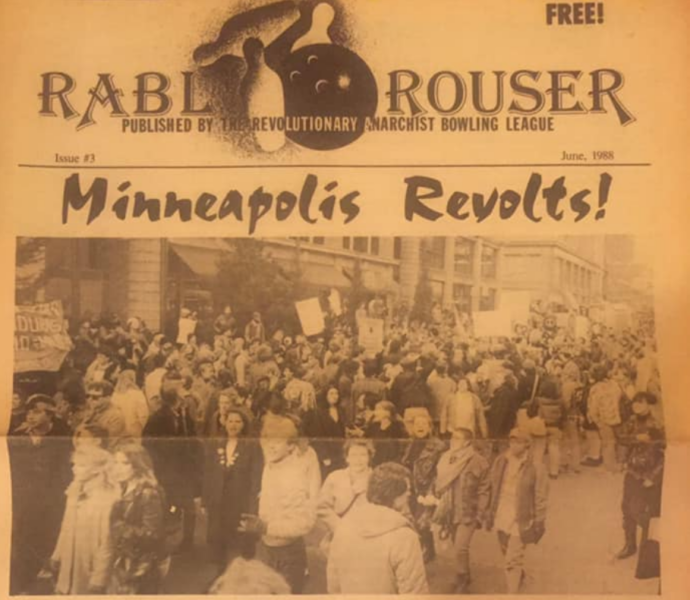

Back Room also played a vital role as a physical space for young punks to use for both social and political purposes. As public “third places” (places to spend time and connect with others outside of the home and workplace) came under attack in the 1980s and much of the political infrastructure from the movements of the 1960s withered away, young punks—especially from suburbs—desperately needed places where they could gather with likeminded people away from the prying eyes of parents and cops. The Back Room provided this space for a generation of Twin Cities youth, thus exposing them to anarchist politics. The Baldies and ARA used it as a mailing address, threw benefit shows and all-ages parties, and hosted meetings there. People came in with a variety of politics which then became subject to sustained discussion. The scene at Back Room thus helped to “elevate and make the conversation more sophisticated.”14 Young punks hanging out at Back Room parties would often pick up the radical literature that lined the walls. One publication they began reading was the RABL Rouser, a new newspaper put out by the Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League.

The Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League (RABL) grew out of what Kieran calls the “action faction” at Back Room Anarchist Books. RABL involved a number of people who had been involved in or supportive of anti-racist skinhead work. RABL played a significant role in the evolution of revolutionary anarchism in the Twin Cities and nationwide in the late 1980s, eventually providing the nucleus around which Love and Rage formed in 1989. Their newspaper RABL Rouserfeatured articles on anarchist theory, feminism, anti-racism, and anti-war activism.

RABL theorized and practiced what they called “revolutionary anarchism.” In “Bowling for Beginners: An Anarchist Primer,” RABL offers an initial definition: “Anarchy is not chaos. Anarchy is the absence of imposed authority. Anarchy is a society that is built on the principles of respect, cooperation and solidarity. Anarchy is wimmin controlling their own bodies, workers controlling their own workplaces, youth controlling their own education and the celebration of cultural difference.” RABL rejected the need for a revolutionary vanguard, arguing that “only the masses, completely involved and in absolute control, can make a real revolution.” In the end, “anarchism is about people empowering themselves to take control and to lead their own lives.”15 But since those in power will not give it up without a fight, revolution is necessary. The basic point of unity for RABL was an agreement on the necessity of revolutionary action to reach a classless, stateless society. RABL brought together the most pro-organization and anti-imperialist anarchists in the Twin Cities—and eventually across the US—in a combination of direct action and revolutionary organization.

Despite their roots in a relatively small city, RABL played an outsized role in transforming US anarchism and organizing the national movement. Anarchists across the country began orienting towards the Minneapolis group; as a member of the Youth Greens later reflected, RABL was “kind of legendary” at the time.16 Kieran describes its importance by saying that RABL was “a great moment of learning how to be an organized anarchist force and how to intervene in struggles, and how to try and build relationships with other forces as well.”17 RABL took the experience of their organizing to the national level as they connected with squatters in NYC’s Lower East Side, anarchist Cuban exiles in Miami, ex-Trotskyists in the Revolutionary Socialist League, and anti-racist punks from the Bay Area to Boston.

In addition to helping build ARA, RABL was one of the main groups behind the birth of Love and Rage. Activists in Back Room and RABL helped organize a series of continental convergences from 1986-89 that revitalized the North American anarchist movement, including the 1987 “Building the Movement” conference in Minneapolis itself.18 At the final gathering in San Francisco in 1989, a series of meetings birthed the Love and Rage newspaper. A core group of anarchists used the newspaper to build a national network of collectives united around the publishing project. After several years of activity, Love and Rage voted at a contentious conference in 1993 to become a more formal membership-based Revolutionary Anarchist Federation. Love and Rage, which dissolved in 1998, had branches across the United States, Canada, and Mexico. It was the most significant revolutionary anarchist organization of the late twentieth century and it indelibly shaped the trajectory of contemporary anarchism. Some of the most important Love and Ragers simultaneously built the national anarchist network and the national ARA network.

Part Three: Love and Rage and Anti-Racist Action

Love and Rage identified its social base as the “reproletarianized” children of the white middle class—a product of deindustrialization and neoliberal globalization—which was the same potential base for fascism in the United States. Love and Rage was predominantly white, whereas Anti-Racist Action was more multiracial. They thus felt that they had a special duty not only to fight fascists in the streets, but also to offer a liberatory alternative to angry young white people looking for radical answers to their problems.19 Anti-fascism became one of Love and Rage’s three main working groups and it collaborated closely with ARA in the struggle against the Far Right.

Kieran helped build Love and Rage and Anti-Racist Action together. Love and Rage helped keep people in different cities connected and built infrastructure including communications structures and local chapters for both organizations. Membership in a national organization lent direction and significance to local actions. For instance, Kieran describes how he went out to Portland, Oregon with a group of people to help fight the Nazis who had taken over the punk scene there. They demonstrated to local activists how to organize and fight. They went after the Nazis in a multi-day spree of fights that left the fascists in disarray.20 Afterwards, Kieran says, “I remember specifically calling Chris who had moved to New York at that time to edit the Love and Rage newspaper. […] I went to a bookstore in Portland and the second issue of Love and Rage was there, which I was excited to see. […] so I called up Chris telling him about [how] the shit I’m seeing is crazy, but it made me feel kind of like there was almost like headquarters I could call to report, you know, what I was seeing and participating in.” Kieran says that whenever he was on the road and doing political work, “I’m thinking about ARA, but I’m also thinking about Love and Rage. […] They were kind of interwoven in my life.”21

The interwoven nature of Love and Rage and ARA in Kieran’s life did not mean that this was the case for everyone in ARA. In the early 1990s, he was one of only a small handful of Love and Ragers who were formally affiliated with ARA. This changed as the years went on and Love and Rage decided to orient towards building Anti-Racist Action and supporting them in actions. But even a very small number of people from an organized group like Love and Rage can have a major impact on the growth of a mass organization like ARA. Back Room Anarchist Books, the Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League, and Love and Rage helped cultivate the politics, strategy, and organizational structure of Anti-Racist Action from the very beginning.

Love and Rage played a key role in developing the street tactics and other actions of Anti-Racist Action. Love and Rage helped introduce black bloc tactics to the US, which ARA embraced as a way to maintain anonymity and carry out more daring actions. Love and Rage collaborated with ARA on militant actions including a major 1993 anti-Klan demonstration in Chattanooga, Tennessee. A local KKK chapter planned a protest of a Gay Pride Parade. Love and Rage helped organize a large counter-demonstration with a range of groups and localities represented. They vowed to run the Klan out of town, by force if necessary. After years of militant action, this promise was backed up by experience. The KKK ended up canceling their own rally to avoid an embarrassing rout.22

Many anti-fascists argued that the Christian Right was a constitutive element of contemporary fascism. In the 1980s-1990s, the overwhelmingly white Christian Right waged war on abortion. Anti-abortion activists in Operation Rescue took to the streets to shut down clinics, advancing the slogan “if you believe abortion is murder, act like it’s murder.” Anarchist anti-fascists mobilized within broad feminist coalitions to protect abortion clinics and defeat the Christian Right in the streets. A major victory came in 1993, when Operation Rescue tried to host a training camp in Minneapolis. Love and Rage helped build an alliance called the Action Coalition for Reproductive Freedom to mobilize against them. Anarchists physically confronted Operation Rescue, blocked them in their church, vandalized their materials, and ran them out of town. An activist named Liza reflected in Love and Rage that “it seems like no matter how hard activists fight, we rarely win. Except this time we were victorious. We fought against these fascists … We saw the demise of Operation Rescue in the Twin Cities, partly due to our unprecedented aggressiveness and opposition.”23

Love and Rage helped cultivate the anarchistic politics and organizational structure of ARA without attempting to take it over. Unlike Marxist-Leninist parties, which often participate in mass organizations with the intention of exercising influence and taking control—whether openly or covertly—Love and Rage members participated in ARA as equals as they helped build the network and organize actions. Love and Rage was opposed to trying to control ARA, in part because they were critical of vanguard parties that they observed trying to take over grassroots movements and mass organizations. For instance, when the ARA network was first forming, a small Trotskyist group tried to create an elected national committee as a formal decision-making body. Many people in ARA denounced this as a power grab and accused the party of wanting power at the leadership level without engaging at the grassroots. More broadly, Kieran reflects that “we thought that it would stifle what was happening with ARA, which was this sort of organic youth movement against fascism that was growing around the country, if it had this sort of centralized leadership that was outside of the local groups.” Kieran didn’t want Love and Rage to act like a vanguard party and insists that “we never tried to impose our own authority over the network.”24

But some non-anarchists criticized Kieran and other anarchists of de facto controlling ARA without owning up to it. One dedicated comrade from the Trotskyist League accused them of controlling ARA behind the scenes.25 The anarchists had explicitly decided not to make anarchism one of the guiding principles of ARA, even though they thought a vote would succeed. But Kieran explains that

we decided against even trying it because we thought it was more important to have ARA be an open place where people could come from different perspectives. […] ARA had an anti-authoritarian sort of culture and ethos already, and it didn’t need to be sort of stifled by something that would kick some people out for no real reason. So I argued back to this Trotskyist that we weren’t trying to [take over], in fact, we decided not to try and do that. And he said, yeah, but you’re controlling ARA spiritually [laughs].26

Yet the Trotskyist had a point. In some ways, denying the leadership role that anarchists like Kieran played within ARA contributed to the problems identified by the feminist Jo Freeman in her influential 1972 critique of the Women’s Liberation Movement, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.” Freeman observed how cliques often coalesced that controlled things behind the scenes without the kind of accountability that could otherwise be exercised through formal leadership structures.27 On balance, however, the more informal approach benefited ARA in its explosive growth. Adopting formal anarchist principles would likely have limited the broad-based appeal of the group. When fighting fascists, it made sense to unite primarily around a set of anti-fascist tactics, rather than around particular ideological lines.

Despite its lack of formal anarchist politics, Kieran says that “ARA had a real anarchist ethos” that stretched beyond Love and Rage. “Love and Rage was just the most organized component of that. But many people, maybe even most of the militants within ARA, the committed people who built groups and went to actions, considered themselves anarchists. And most of them weren’t in Love and Rage, even if some of the most important people were, and some of the most important chapters were.”28 This exemplifies the role that Love and Rage played as a pole of anarchist attraction within social movements. Only a small minority of US anarchists were ever part of Love and Rage, but it played an outsized role in ARA and other grassroots movements because of its strong organization and national newspaper. They helped contribute to the development of ARA’s revolutionary anti-fascist analysis.

An early political divide within ARA was between anti-capitalist/anti-imperialist radicals on the one side, and a “pro-American” faction on the other. The pro-American side often wore American flag patches and identified with what they saw as the positive, democratic, and anti-fascist aspects of US history, from its basis as a multi-racial society to its role in defeating the Nazis in World War II. From this perspective, racist skinheads were “un-American” and should be fought in the name of what is actually good about the country.29 This line held some appeal, and it helps explain the widespread appeal of ARA even in relatively conservative, white dominated places throughout the Midwest. A sizeable number of white people simply hate Nazis and Klansmen and feel some sort of humanistic and patriotic duty to combat them. But Kieran and other anarchists were critical of this and pushed ARA to acknowledge the fundamental white supremacy of American history and ruling institutions. Love and Rage and anarchism more broadly gave them the analysis and terminology to argue for radical anti-imperialist politics and connect anti-fascism with the broader struggle for liberation in (and against) the United States. The “Pro-Ams” were isolated in ARA, and most soon left to join less radical anti-racist skinhead groups.

ARA militants went on to formalize the “three way fight” analysis of fascism and anti-fascism. Yet throughout the 1990s, Love and Rage had already been practicing it. Love and Ragers threw themselves into building ARA and fighting fascists in the streets, but they never collaborated with the state to repress fascists. Rather, they argued that anarchists must present a radical alternative to both fascism and the capitalist system. White supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy, and the state were all entangled and must be fought together. In the end, Love and Rage insisted, only an autonomous revolutionary movement could defeat fascism and capitalism alike. While they failed to overthrow capitalism, ARA’s sustained offensive across the United States and Canada played a central role in disrupting the fascist movement in the late twentieth century.

Conclusion

Organized anarchists played a leading role in the birth and development of Anti-Racist Action in the 1980s and 1990s. In Minneapolis, Back Room Anarchist Books and the Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League provided spaces and political models that helped radicalize a generation of young punks and provide an analytical edge in their life-and-death fight against Nazis in the punk scene. This was crucial for the early anti-racist skinhead group the Baldies as they founded Anti-Racist Action and expanded their struggle against white supremacy. Love and Rage then helped to build a national ARA network and contributed to tactical and ideological struggles against fascism. They helped maintain the anarchistic politics and structures that made ARA effective, uniting around a set of tactics rather than a rigid ideological line. But they also worked with unorthodox Marxists to develop an analysis of revolutionary anti-fascism predicated on the idea of the “three way fight” against the capitalist state and the fascist right. This is one of their most important legacies, which continues to guide the fight against fascism today.

The liberal repudiation of fascism through the defense of electoral democracy and mainstream institutions is not enough. Many on the Left today, including the moderate wing of the Democratic Socialists of America, have rallied behind the Democrats to defend democratic institutions against the insurrectionary threat of the fascist right. Although this may achieve certain short-term goals, including the prosecution of the January 6th conspirators, it is ultimately a losing strategy. Fascists are responding to a real crisis of liberal democratic capitalism that cannot be solved on its own terms. When the Left joins liberals in defending mainstream institutions, fascists are emboldened to present themselves as the only real alternative to the status quo. There is a three way struggle between the anti-fascist Left, the current capitalist system, and the fascist right. The anti-fascist Left must struggle against both capitalism and fascism using different tactics. On the one hand, we need to organize mass movements that address the root causes of our social crisis and fight for a better world. Simultaneously, as Anti-Racist Action demonstrated decades ago, anti-fascists must act now to defend targeted communities and address the imminent threat of fascist groups before their own violent alternative to liberalism becomes entrenched.

Spencer Beswick (he/him) holds a PhD from Cornell University. His dissertation, “Love and Rage: Revolutionary Anarchism in the Late Twentieth Century,” explores the transformation and revitalization of the US anarchist movement in the 1980s-1990s. He is one of the organizers of the Anarchist Oral History Project. Spencer has been active with a number of radical projects since his life was transformed by Occupy Boston in 2011, including labor organizing, Food Not Bombs, Ithaca’s Antidote Infoshop, DSA, and PM Press.

Notes

- “Anti-Racist Action Network Four Points of Unity.” Turning the Tide 24, no. 3 (Jul-Sep 2011), 4.

- Mark Bray, Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, xv.

- See for instance Mark Bray’s Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook, 71, and We Go Where They Go: The Story of Anti-Racist Action, Oakland: PM Press, 2023 by Shannon Clay, Lady, Kristin Schwartz, and Michael Staudenmaier.

- See Kathleen Belew’s Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- See Matthew Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire. Oakland: Kersplebedeb and PM Press, 2018.

- Robert Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism, 218.

- See Don Hamerquist’s summary of this history in “Fascism & Anti-Fascism” in Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement, 29-36. This summary glosses over some of the twists and turns of the Comintern’s strategy, including the infamous 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

- Don Hamerquist, “Fascism & Anti-Fascism,” 44.

- Don Hamerquist, “Fascism & Anti-Fascism,” 44.

- “About Three Way Fight.” (2013) http://threewayfight.blogspot.com/p/about.html

- “About Three Way Fight.” (2013) http://threewayfight.blogspot.com/p/about.html. For an excellent book length examination of the history of fascism in the postwar period from one of the leading Three Way Fight analysists, see Matthew Lyons, Insurgent Supremacists (2018).

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League, “Bowling for Beginners: An Anarchist Primer,” 12.

- Lee Schere, interview with author, November 19, 2021.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- See Spencer Beswick, “From the Ashes of the Old: Anarchism Reborn in a Counterrevolutionary Age (1970s-1990s)” Anarchist Studies 30, no. 2 (2022) and Leslie Wood, “Anarchist Gatherings 1986-2017” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 18, no. 4 (2019).

- Chris Day, “Love and Rage in the New World Order” (1994). See Spencer Beswick, “Smashing Whiteness: Race, Class, and Punk Culture in the Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation (1989-98),” in DIY or Die!: Anarchism, Punk, and Do-It-Together Production of Culture and Space, edited by Jim Donaghey, Will Boisseau, and Caroline Kaltefleiter. Karlovac, Croatia: Active Distribution, forthcoming 2023.

- For a history of Anti-Racist Action in Portland, see the podcast series “It Did Happen Here” (2020-21) and the book based on it, It Did Happen Here: An Antifascist People’s History edited by Moe Bowstern, Mic Crenshaw, Alec Dunn, Celina Flores, Julie Perini, and Erin Yanke, Oakland: PM Press, 2023.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- See John Johnson, “Anti-Fascists Converge on Chattanooga.”

- Liza, “Minnesota Not Nice to Operation Rescue,” Love and Rage 4, no. 4 (1993), 19. For more on anarcha-feminism and abortion struggles, see Spencer Beswick, “‘We’re Pro-Choice and We Riot!’: Anarcha-Feminism in Love and Rage (1989-98),” Coils of the Serpent no. 11 (2023).

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- Jo Freeman, “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” (1972).

- Kieran Frazier, interview with author, March 12, 2022.

- See the discussion of the “Pro-American” skinheads in We Go Where They Go, 41.

Works Cited

“About Three Way Fight.” (2013) http://threewayfight.blogspot.com/p/about.html

“Anti-Racist Action Network Four Points of Unity.” Turning the Tide 24, no. 3 (2011).

Belew, Kathleen. Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Beswick, Spencer. “From the Ashes of the Old: Anarchism Reborn in a Counterrevolutionary Age (1970s-1990s).” Anarchist Studies 30, no. 2 (2022).

Beswick, Spencer. “Smashing Whiteness: Race, Class, and Punk Culture in the Love and Rage Revolutionary Anarchist Federation (1989-98).” Forthcoming with Active Distribution 2023.

Beswick, Spencer. “‘We’re Pro-Choice and We Riot!’: Anarcha-Feminism in Love and Rage (1989-98). Coils of the Serpent (forthcoming 2023).

Bowstern, Moe, et al. It Did Happen Here: An Antifascist People’s History. Oakland: PM Press, 2023.

Bray, Mark. Antifa: The Anti-Fascist Handbook. Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2017.

Clay, Shannon, et al. We Go Where They Go: The Story of Anti-Racist Action. Oakland: PM Press, 2023.

Day, Christopher. “Love and Rage in the New World Order.” In Roy San Filippo (ed.), A New World in our Hearts.Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2003.

Frazier, Kieran. Interview with author. March 12, 2022.

Freeman, Jo. “The Tyranny of Structurelessness.” (1972).

Gunderson, Christopher. Interview with author. Oct 8, 2021.

Hamerquist, Don. “Fascism & Anti-Fascism” in Confronting Fascism: Discussion Documents for a Militant Movement(2022)

Johnson, John. “Anti-Fascists Converge on Chattanooga.” Love and Rage 4, no. 5 (1993).

Liza, “Minnesota Not Nice to Operation Rescue,” Love and Rage 4, no. 4 (1993).

Lyons, Matthew. Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire. Oakland: Kersplebedeb and PM Press, 2018.

Paxton, Robert. The Anatomy of Fascism. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004.

Revolutionary Anarchist Bowling League. “Bowling For Beginners: An Anarchist Primer.” Love and Rage 1, no. 5 (1990).

Ross, Alexander Reid. Against the Fascist Creep. Oakland: AK Press, 2017.

Schere, Lee. Interview with Author. November 19, 2021.

Trotsky, Leon. “Fascism: What it is and how to fight it.” 1944. Accessed at https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/works/1944/1944-fas.htm.

Wood, Leslie. “Anarchist Gatherings 1986-2017.” ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 18, no. 4 (2019).