By Charlie Allison

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling’s new book If It Sounds Like A Quack came out earlier this year and can be purchased here. It talks about the rise of the medical freedom movement in American, the corporate take over of the medical industry and the ascendancy of what he calls One True Cures—treatments that range from leeches to lasers and purport to be able to heal all ills.His previous book, A Libertarian Walks into A Bear examined the role of libertarians cutting social services in a rural New Hampshire Town—with ursine results.

Charlie: I guess I want to start this interview with a question of how you went from your previous book (A LIBERTARIAN WALKS INTO A BEAR) about the Free State libertarians gutting social services in Grafton, NH only to meet with a surprising bear-backlash, into One True Cures.Matt: Thank you for asking. I’m really excited to be talking about this book. I was coming up with my book idea in the early stages of the pandemic. There were a lot of salient, pertinent questions about where the rights of the individual ended and where the right of government to curtail those rights in the name of public safety began. So, those discussions were playing out everywhere, all over the place, and so I was looking for a fresh take on that. I thought I’d reach out to folks who had some sort of conflict with the system—people who’d been sanctioned by the FDA or come into some sort of other conflict with the law. When I started talking to those healers, and asking them how the FDA ought to be reformed, there wasn’t any nuance to their position. I’d ask them:“What changes would you make at the FDA?”And they’d say:“I’d abolish the FDA.”

In the course of those early conversations it became clear to me that these people, most of whom started out as good people out to improve the world, had been politically radicalized and adopted a whole set of political views that are right wing talking points, basically.

That was kinda a surprise to me. I didn’t expect a political lean to the world of alternative medicine practitioners that I’d personally always associated with the hippy-dippy-left. As I began to realize how extreme they had become politically and how detached from reality some of their understanding views of healing and science were, I realized I had to write that book instead.

Now, how does that springboard into your question on Grafton thing? Only that my starting point was both books have to due with the subject of freedom and individual rights—before I was done researching, I had learned about another facet of the libertarian doctrine in healthcare. But it wasn’t my intention to write another libertarian-centric book.

Charlie: I’m actually really curious if there are any people involved in the Free State Movement that turned up in early drafts of this book as connectors or whether it was more in principle.

Matt: Oh that’s really interesting. It never occurred to me. I did early in my research, reach out to a couple of Free Staters who seemed to be centered on the idea of medical freedom, or health freedom. But I never succeeded in making those connections and having those conversations. Since I was more focused on the national scene anyway, you know, more on a connection of local scenes across the whole country, I didn’t pursue that too hard.

Charlie: Gotcha. The people you selected and wrote about are plenty interesting. I’m actually really curious, you mentioned this, I believe, in your book, and you alluded to it in your previous answer—the sort of positions determining politics or identities determining politics rather than one’s thoughts on it.

Like, if you are a ‘good Republican’ or a ‘good libertarian’ you must be anti-vaccine all the time as a sort of a formula that unspooled.

Matt: I think when I went into the book I assumed that a lot of people were anti vaccine and therefor, political parties began to adopt those anti-vaccine views in order to capture the minds and hearts of those people. That it was a grassroots-driven belief. But what I found was that research that I cite in the book shows that it was the other way around. That people don’t come to their positions on vaccines because of the science of vaccines, or because of their own personal feelings about vaccines. They first identify with a tribe—as a Republican, or a Democrat or a libertarian or green—and whatever the other folks in that tribe seem to feel, that is the position that they take.

That position is driven by the loudest speakers in the tribe, kind of their representatives. In this case, within the Republican party and the more right wing and conservative flank of the party, there were a lot of loud voices that were anti-vaccine. And that is how the rank-and-file Republican came to take up that view. By the way, that’s how the rank and file Democrat came to take up their staunch pro-vaccine view.

Even though I would argue that reality reflects a democratic position in that case, I think that if there were a lot of influential democratic leaders who could take the story-line that “We don’t trust the Covid vaccine because Trump pushed it through the FDA”, I think you might see an exact reversal of the partisan positions right now. If Democrats had never abandoned that viewpoint—being wary of the vaccine that Trump pushed through the FDA—the prominent voices within the party structure never took that up and told their followers not to get vaccinated. At the time there were a few Republican voices that were saying “Look at this vaccine that Donald Trump got us, he’s gotten the vaccine out” but those voices didn’t continue. It doesn’t take too much thinking to see that it could have gone the other way.

Charlie: That’s a chilling sort of top-down formation of identity, right?

Matt: Yeah. For sure. Unless Bernie Sanders gets elected because he really reflects the people.

Charlie: I wonder if you saw the Surgeon Generals report on the health effects of loneliness as a national epidemic. Something like the health risks of loneliness as being unaddressed in American society—that we are more atomized and polarized and isolated than ever.

Matt: I’m not familiar with that report but its not a new idea to me. I’ve read from several sources accounts that track back everything from a spike in suicide ideation among teens to feelings of depression among young people to certain health risks for seniors who are not connected to the broader society in the way that they might have been in a different era in our history. All suffer greatly because of that isolation that’s kinda like an increasing facet of our world. More people working from home, more people spending their off hours on a screen rather than out and having face-to-face conversations—we’re all very aware of these digital bubbles we’re surrounding ourselves in that reinforce and affirm our views—and demonize the views of our political opponents. When I look at a Twitter feed or a social media feed it tends to show me the very worst 1% of Republicans, right?

When I go out in daily life and I meet Republicans in my community, I certainly meet people like that but I also meet a lot of Republicans with a different philosophy on what would be best for America—they aren’t really mustache-twirling villains that we see as a representative sample. I know that on the other side, conservatives are looking at their social media feeds and seeing the same—saying “that’s all that the democratic party is, isn’t that terrible?” Again, not really representative.

I think that the Democrats I speak with understand the pitfalls of social justice approaches to systemic oppression—that’s a healthy and important thing to know—not everyone speaking on a social justice issue is perhaps approaching it with a well intentioned heart—there’s the danger of being seen as performative and its important to say that those folks don’t represent the broader movement.

Charlie: I think that what I meant to ask is: do you think that in the process of writing your book that the sort of alienation and isolation from broader communities has combined with the stripping of healthcare and autonomy to health create these One True Cure communities in a desperate attempt to create something to believe in?

Matt: Oh, that’s interesting. So you’re saying like ‘Are the One True Cure’ types offering something that fills the whole left by human interactions?

Charlie: Something like that. I believe there is a section in the book—the woman who started with cancer and then got the terminal kind because of the Alkaline Diet treatment—the analysis from her end seemed to be: “I can get community her [with the Alkaline diet people] which will actually kill me vs. the very impersonal and expensive medical system, which, while bad, will also let me not die or at least slow my dying.”

Matt: Right, right. Absolutely. I don’t know that I’ve never thought about it as an expression or result of that broader form of isolation that you are talking about—I think of it as more of the impersonality of bureaucracy and the lack of humanity in folks who get so caught up in the data and balance sheets that they do not have any room to care for the individual member of the public that they serve. The culture of bureaucracy and medicine both leave a lot to be desired and so the culture of bureaucratic medicine even more so. When those things overlap it can be so off-putting to John Q. Public or to Dawn Cali, the cancer victim you mentioned, that they would much rather go to somebody who would treat them like a human—with respect and kindness and tell them what they want to hear—except for as you say, the fact that they’ll die. If it wasn’t for the dying thing, it would be great.

Charlie: I feel like I need to ask a craft question: one of the things I really appreciate about your work is that you’re able to tell very human stories and show people with their masks on and off—but still make it very very funny. I guess the short version of this question is do the jokes in your work come as your write or do you have a set of jokes as you investigate topic—like a file of jokes or puns set aside for later?

Matt: I wish I could give you a more clear answer than that, but there are definitely times where I will make an observation and say “that’s a really funny thing” then wait for the opportunity to shoe-horn it into the text somewhere. Or a funny phrase or something will occur to me. I was listening to a podcast called Futility Closet—they do quirky little stories from history. I appreciate it because it’s lively nonfiction narratives and that’s instructive for me, something I wanna emulate. They had a show segment where they talked about medical semantic variables. The idea is that its a word that can mean any word—like ‘Smurfs’.Charlie: Oh, you did that in your book! I loved that segment.Matt: Exactly. So I was like “oh, that’s a really interesting concept—I’d love to talk about that”. I find that really funny, I never thought of there being a word for that thing. ‘Smurf’, ‘I am Groot’ and ‘Yada yada yada’ belonging to a category of speech that had an actual name. So I wanted to use that, and I finally got an opportunity to use that to describe the psuedoscience that’s used by the practitioners of the One True Cures. I was happy to find a place to shoe-horn that in—you know there were other times where someone says something funny and I’m just focusing on the funny thing that they said. Or noticing the human foibles and flaws that we all suffer with.

Charlie: It is such a cool concept, the variables. It’s especially fun in English, which is like 8 or 9 languages in a trenchcoat.

Matt: That’s funny. It’s the Muppetman of languages.

Charlie: English is kinda a bully in the sense that it breaks its own rules all the time and penalizes you for noticing that fact. Anyway, was there a particular part of the book that was most emotionally demanding to write?

Matt: Without a doubt it was the death of Cara Newman, who I think I said this recently on a podcast for something, I don’t know if it was the saddest story that I’ve ever heard, but it was the saddest story that I ever had to really have my nose rubbed in. You know, really think about it for weeks and weeks on end and research every little detail of her death and communicate it to the readers. It’s sad when a child dies senselessly and is essentially dead because of her parents falling down on the job and yet her parents are doing what they think will help her and its not. It’s a really tragic situation all around. It shows just how far, just how deadly misinformation can go and be.

Charlie: If I am remembering rightly, her Cara Newman’s father was holding out for a resurrection after her death?

Matt: Yeah. They were holding prayer circles and calling extended family saying “Please pray for Cara” and it’s Easter Sunday so it’s a great setup for a resurrection narrative. A young woman who had just married into the extended family, heard that this little girl was in a coma and called the authorities. She connected to a policeman on Easter Sunday and they sent out an ambulance and it got their three minutes after she took her last breath—it could not have been closer or more nail-bitingly sad. The parents were so invested in this idea of faith healing that they believed God must be doing this for a reason and the reason that they thought was that Cara was going to be resurrected. They were literally praying around her corpse in the hospital.

Their spiritual leader was also speaking that language—was talking this fantasy that Cara was going to come back to life. After the autopsy was when reality began to settle in for them. Its worth noting that even now they are listening to spiritual leaders who promote faith healing and advocating health cures that doe not work—fasting, all sorts of other nonsense. It’s really sad and I feel awful for them that they lost their daughter. I also feel angry because she died on their watch and they don’t seem to have learned any larger lesson from that other than how right they were in the first place and how bad society is for looking down on them,

Charlie: I believe, correctly on the last name because I don’t have the text in front of me that the Newmans had a theological dispute with their neighbors. These neighbors were also big into the power of prayer and also big into the power of basic human health and doctor-checkups. They had a split because of this belief. There is a difference between being a very religious person and being a very religious person who believes that the very concept of medicine is an affront to God’s authority.

Matt: Yes, the Wormboughs, that other family, they were gonna start a ministry with the Newmans. Join the large families together to be the nucleus of a community. Again, some—most—evangelicals who are of the pentecostal faith believe that doctors are there by the glory of god and that god has put doctors there to heal you. But the Newmans and other people on the fringes of faith believe that god heals you directly. Its a very kind of populist view, I suppose—anybody can heal through prayer, anyone can access god through prayer, we’re all equal under god’s loving embrace etc. As a result, if you go to a doctor, that’s an expression of lack of faith. So no doctors. Until the end. And obviously that’s a really damaging idea.

Charlie: It sound so benign until you start to go through what it implies, what logically follows.

Matt: If you’re reading the Bible, I mean why not? The Bible is a little messy, difficult to understand, you can draw a lot of contradictory lessons from it, it’s as good a basis for that view as the opposing one [in regards to medicine].

At this point, we lost about half the interview (because I forgot to hit the record button when the meeting refreshed.) However, these are the main beats of the lost conversation:

-Decolonizing and decentralizing American healthcare in the name of health justice.

-Some reference to Michael Fine’s work Medicine as Colonialism about possible ways of achieving health justice through strikes and local control of doctors in communities rather than through corporations.

-And of course, the steam doctors—who waged war on the early administrative state and succeeded in getting medical research and development stalled for over thirty years in the name of personal profit—and sometimes steaming their clients to death in order to ‘cure’ them. Our interview resumes here.

Charlie: So we’re talking about steam doctors and advertising ruining trust in the public good. Owning the libs and putting ivemectin during the peak of Covid sounds similar.

Matt: Yeah, that’s the narrative and the very human flaw—wanting to be the roadrunner to society’s Wile E. Coyote, right? You want to portray yourself like this: “Ha! They’re angry and upset and they’re trying to get me but I fooled them again! I took the ivemectin!”

Charlie: Truly, this will have no consequences.

Matt: Right, right.

Charlie: So that gets to something interesting, an interesting point about the systems of One True Cures. Reading your book I came away with the thought that they kind of depend on the medical establishment existing, as much as they rail against it—without this contrast, would people go to them? I don’t know the answer but {shrugs} question mark?

Matt: I think that clearly the system is so dysfunctional and flawed that it is driving people into the arms of these quacks who are worse. People are leaving the bad and embracing the worst. So I suppose that if you de-centralize everything, its almost like a free-market argument. To have a pure free market—as they did in Samuel Thompson’s day in the 1800s—was not a good solution. Not only did a lot of people get steamed to death by the steam doctors and their allies, but in addition, the sort of medical progress that is made through institutions and research and academia—that was all set back 30 years in this country. Only the civil war restarted America’s desire for institutional medicine.

Charlie: That is…a part of history I had no idea about.

Matt: It’s a little hidden but, like today’s Medical Freedom movement, there were riots back then over this. The most famous of which were the Anatomy Riots. They weren’t expressly part of the medical freedom movement but it’s part of the populist movement—very anti-doctor. The issue that really drove them to anger was the idea that a doctor was robbing a grave to do anatomy experiments.

Charlie: Was that similar to Burke and Haire? Famous grave-robbers and also doctors. [Fact checking revealed that Burke and Hare were in fact worse than just doctors who dabbled in grave-robbing—they rose to notoriety because they killed their victims THEN sold the bodies for medical experiments. ]

Matt: They were in England, right? That sounds familiar.

Charlie: Yep.

Matt: Same idea, same idea. So some farmer’s daughter’s body would go missing from her casket, the people in the community would lose their minds and go to the local medical school with pitchforks. There were 30 or so riots like this over the course of several years resulting in some deaths and that is a similar dynamic to what’s at play today.If you decentralize it [healthcare] you’d need some sort of method of insuring transparency of results for sure. You’d have to overcome the fact that people who are bad at medicine but good at marketing can attract patients. You have to defeat that somehow—tie the marketing to the actual evidence. I don’t know what that system looks like without a bureaucracy.

Charlie: Yeah, that’s a hell of a question. Especially because the tendency for bureaucracy to assume every place is the same and erase local differences is, I would argue, one of it’s greatest weaknesses.

Matt: Yeah.Charlie: So you’d need—I’m spitballing here—some kind of anarcho-syndicalist approach to medical R&D—you know, elected federated councils of people who love doing this sort of research work with no particular bonuses or privileges. A sort of distributed love of the game of research, I guess.

Matt: If you take money out of the system it starts to look more achievable.

Charlie: If you take money out of the system it looks like something you could understand or better yet, explain to someone in under twenty minutes over a cup of coffee.

Matt: Yeah, or a hyper-local situation. The charlatan is under the thumb of a local official who can ensure some level of protection. Doing it in this way would encourage your local family doctor who grew up in the community and maybe had the key connections. That was the saving grace of Thomson in the 1800s—that was what the steam doctors had going for them. They couldn’t cure anybody, but they had great relationships with their patients. And that is what won them public favor at that time.

Charlie: It’s so fascinating to try to piece together such disparate things. I mean, the good people skills vs. the if you drink this it will be very bad for you.

Matt: ‘But he seemed so nice, what possible reason could I have NOT to drink this’?

Charlie: ‘What possible reason could he have to sell me things that would hurt me unless doing so would allow him to sell MORE things that would hurt me?’ I think that good news is—in your book I mean—is that the idea of the political imagination is going to be key to any sort of health justice.

By reading your work, I think you did a really good job making the reader see the leaders of the One True Cure people as people before they became capital-A Authority. Before their ego gets so fragile and the sunk cost-fallacy has kicked in for them to admit that the slightest deviation brings the whole system they’ve constructed down. Knowing them as people—you give a good deal of hope for political imagination and local organizing around this issue and bringing new structures into existence around actual medicine.

Matt: The One True Curists are fascists in the sense that they have a body of evidence that is completely dogmatic and completely resistant to change. They will only change their offerings based on the profit potential. The guy who is selling lasers [to cure every and all possible human ills] is gonna be selling lasers til the day he dies, whether its effective or its not effective. If the evidence is murky in the beginning, the increasing clarity of the evidence showing that this is not effective is not going to change his sales potential. He’s just gonna go to places where he can make his argument.

Charlie: The fellow you’re referring to, didn’t he end up selling his lasers out of northern Russia?Matt: Yep! And telling the authorities that he sold them out to Alabahad India—nothing to do with him! Its a really sticky wicket, clearly what we have is broken. Clearly what these people are offering is worse. I think you’re right-imagination and health justice are really key guiding principles. This structure is indeed much more problematic than the actual body of evidence that doctors rely upon. How do you continue to help cancer patient with cancer research, a process that costs millions of dollars, without becoming a puppet of Big Pharma and dehumanizing everybody?

Charlie: Who knows what the future brings—and that is either very ominous or very hopeful depending on inflection.

Matt: Yeah. It’s a question of whether we can tame the monster or whether we have to throw it away.

Charlie: So I have to ask—what is your next book?

Matt: So I am working on a book—I’m trying to think about what I can say publicly—its to do with the paranormal enthusiast community. I can say that. I’m taking an anthropological look at them.

Charlie: I bet dollars to donuts you’re going to involve MUFON.

Matt: MUFON is a bit too well known—I feel like other people have already covered them very well. In my last book I was writing about criminals who were hurting the public health. I’m happy to report in the the paranormal community, they aren’t out there doing that. As institutions falter, the trust that people once put in institutions and the power that comes with that trust is going to groups like paranormal investigators. So, who are these people? What are they all about? Are they helping the people that they serve, their clients, should we think of them as a nascent, not quite developed class like psychologists out there helping people through their own problems? Or is there something about them or the views that they espouse that makes them fundamentally incompatible with any sort of structural emergence?

Charlie: The last big paranormal movement I’m aware of was the Spiritualists and I wonder what broke them in the end.

Matt: Science. Science broke them. Society has come to fetishize science—myself include—science has a much higher place in the world right now than it did 100 years ago. The inability of non-scientific institutions to produce results that were driving the Spiritualist appetite—you know maybe you can read the squiggly cards at a higher rate if you’re psychic—but that didn’t track with any of the full-throated narratives of raising the dead or the like. That didn’t show up in any laboratory and kinda died out. Well, guess what, it’s back and it’s in a new form and it’s kinda a mix between Ghostbusters and ghost hunters.

Charlie: I mean, Arthur Conan Doyle was convinced that he would come back from the dead—his friends left an empty chair for him at one of their weekly meetings I think. He famously did NOT come back from the dead but ‘big if true,’ to use your own words.

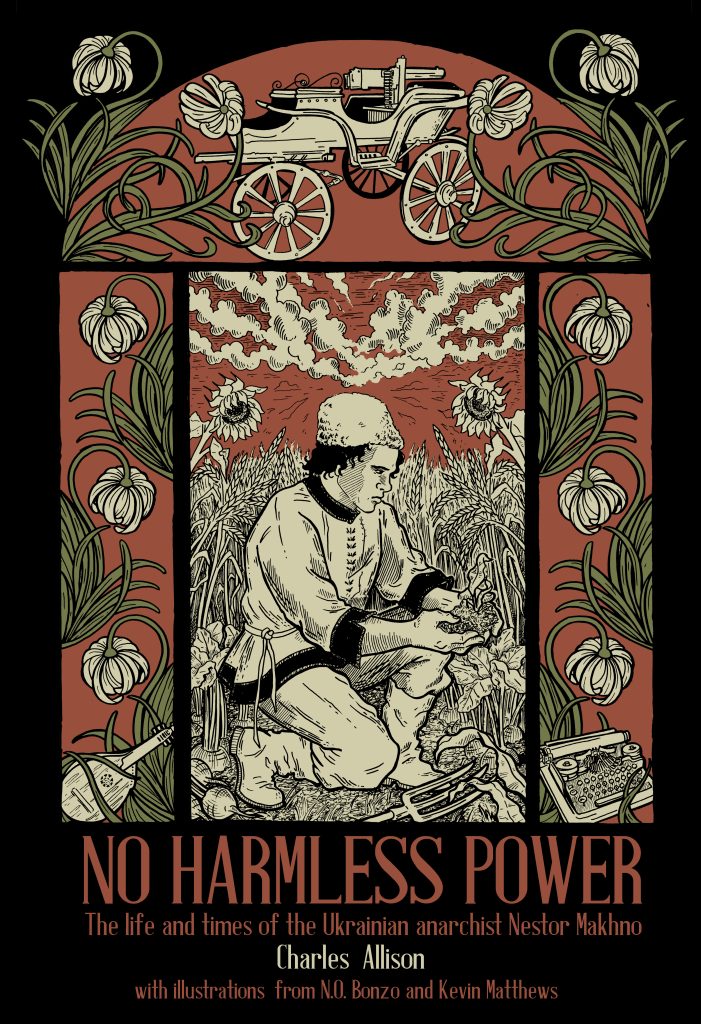

Check out Charlie’s forthcoming book: