By Luke O’Neil

Welcome to Hell World

April 23rd, 2023

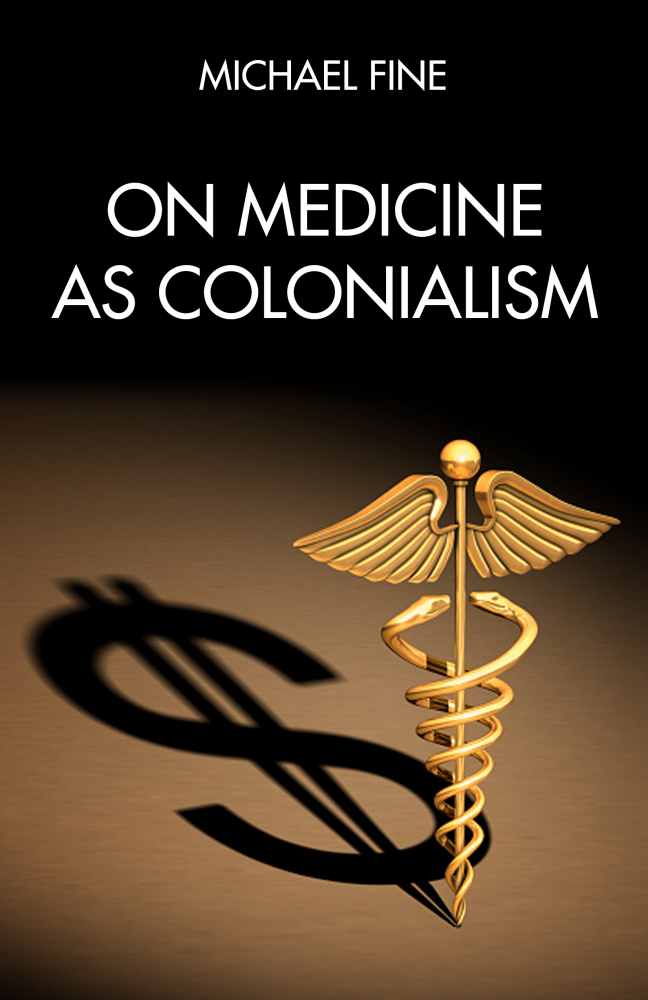

Today we have an excerpt from the book On Medicine as Colonialism by Michael Fine which you can find here via PM Press.

“What if communities where the pandemic hit were just the raw materials of this process, the place where the gold is mined, the oil is extracted, the rubber or banana trees are grown, and the people are just the providers of labor and consumers of manufactured goods made elsewhere?” Fine writes.

“What if medicine wasn’t about health or health care or the pursuit of happiness or democracy at all? What if medicine was just colonialism?”

Two Stories and a Definition

by Michael Fine

In Central Falls, Rhode Island, where I work, the COVID-19 pandemic hit hard. People who live in Central Falls, the smallest and poorest city in Rhode Island, live in densely packed houses, often eight or ten people to a two-bedroom apartment, sharing one bathroom and kitchen. Many are undocumented immigrants. Most work two or three jobs to feed their families and send money home to family members in Central America, the Caribbean, or West Africa.

When Rhode Island shut down in March 2020, everyone forgot about the people in Central Falls. When Governor Gina Raimondo closed the state, she did everything she could to preserve the economy. That meant keeping essential services and factories open. Teachers, bureaucrats, administrators, lawyers, and even doctors started working from home. But the people of Central Falls kept working away from their homes—working with other people. Construction workers. Factory workers. Bus drivers. Certified nursing assistants. Store clerks. Landscapers. These people went to work every day, in part because they had to. Undocumented people don’t qualify for unemployment insurance or stimulus checks. People in Central Falls kept working so they could pay the rent and the phone bill and buy food. Among people of color in Central Falls—who make up the majority of the city’s population—only about 10 percent have the kinds of jobs that would allow them to work from home. Even so, 20 percent of the city’s workers became unemployed, at least legally. Most people, employed or not, continued to work under the table if they could, just to make sure their families were fed.

So people went to work, and they got sick. By April 2020, Central Falls became the most infected place in the United States and one of the most infected places in the world. More infected than anywhere in New York City. More infected than Italy or Great Britain. More infected than Wuhan. We found out about how the virus was spreading the hard way, because there was almost no testing in Central Falls, at least at first. People died in their homes, afraid to seek medical advice. Whole families got sick. In those apartments of eight or ten people, many workers got sick at work, brought the virus home, and spread it to everyone in their households. In April 2020, there were four deaths at home from COVID-19, and doctors’ offices were overwhelmed by the number of people who were ill and had no place to go.

In late April, after weeks of begging for help from the state health department, the state government, and the federal government, the cities of Central Falls and Pawtucket got together and stood up to create an Incident Command System (ICS), the usual response of emergency personnel to emergencies of various sorts, from fires and hostage taking to hurricanes. In those cities of one hundred thousand people combined, likely fifty thousand lacked primary care doctors. The local hospital had closed the year before after years of low occupancy, the result of changing demographics, poor management choices, and market-driven competition from larger hospitals just a few miles away. There was no one else to care for the population and no one else to fight the pandemic in the two cities. These cities had no public health experience and had never used ICS for a public health emergency, but there was no other choice: after weeks of begging, pleading, and cajoling state and federal officials, it had become clear that no help was on the way.

We’ll do it ourselves, the cities said. We’ll use volunteers and city employees. We’ll collaborate with community organizations, who we’ll invite to the ICS from the outset. We’ll build our own testing system. Our own phone consultation service, so that people who are sick can get medical help. Our own family support system, so that undocumented people can get food and cash to sustain them should they get sick. Even our own public health process to help people who are sick and in isolation and quarantine, because the state’s isolation and quarantine systems have miserably failed. Our own data system, because there isn’t much good data available about how the virus is infecting people in Central Falls and Pawtucket.

The cities brought together those city workers and volunteers and built that system around a hotline inside of two weeks. I was the chief health strategist for the City of Central Falls as well as the health advisor to the mayor of the City of Pawtucket. I knew both cities well, and I also knew the health policy landscape at the state and federal level like the back of my hand. I had done my residency in the hospital that had closed, had practiced in both cities, and had served as the director of the Rhode Island Department of Health after that.

The ICS process worked like a charm. Inside of two weeks, we built a little health care system for one hundred thousand people that brought telephonic medical care, isolation counseling, testing, and family support to the people who got infected in the first wave of COVID-19. Four languages— English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Cape Verdean Creole—were available by phone. Our little health care system required only a phone number and a nickname from each caller—not even a real name, so we wouldn’t scare off undocumented people. We had volunteer doctors, nurse-practitioners, and midwives on the phones. Volunteer pre-med students did isolation and quarantine counseling, helping people who were sick understand how to separate themselves from others so they didn’t spread the disease.

The cities funded the process themselves in the short run— and requested $800,000 in state aid to make it sustainable. Over a billion dollars of federal pandemic aid flowed into the state in that period. Central Falls and Pawtucket hoped that a tiny portion of that $1 billion—less than one-tenth of 1 percent— would come to their cities so they could continue the critical public health work they had started pretty much on their own, when neither the state nor the federal government could organize itself to help protect the two cities’ citizens.

But everything changed as soon as money came into the picture. There were meetings on top of meetings—not to respond to the public health emergency, but now to discuss the cities’ request to fund their public health response. All of a sudden, as a budget was negotiated, there were lots of people on lots of Zoom calls. A new entity appeared in these virtual meetings: the local branch of a national organization called Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), which is a housing organization, had contracted with the state to run something called the Pawtucket–Central Falls Health Equity Zone (HEZ). The state had decided to send all funds to LISC, not to either city. Everyone involved in the ICS process lived in or worked for the cities of Central Falls and Pawtucket, and most people (except me!) both lived and worked in one of the cities—and most involved were people of color who spoke either Spanish or Cape Verdean Creole. But none of LISC’s employees lived in either city, and none of the LISC employees or any of the other state contractors—who worked for national consulting groups like the Boston Consulting Group or Alvarez & Marsal and who sometimes appeared as if from nowhere on these calls—either lived in one of the cities or spoke Spanish or Creole.

Finally, after three months of these calls, the state sent LISC $175,000 to use for the cities’ pandemic response. Only $175,000, instead of the $800,000 the cities thought it would cost to run a full-fledged public health response. LISC made a deal with a large politically connected (and privately held) business headquartered in the one of the cities, a business that had been idled by the pandemic, to supply the 800 number and the information technology needed to run the hotline, and it also doled out money to community organizations that had been part of ISC and had been doing this work all along.

But when the $175,000 finally started to flow, it was too little and too late to stop the fall surge of COVID-19. And the money went not to the people of Central Falls and Pawtucket, but instead mostly to that large privately held corporation (a campaign contributor to one of the mayors), whose owners and most of whose employees lived in other places.

And then things got worse. While this process had been running with volunteers, a Latino guy who worked for the privately held corporation and lived in one of the cities had over seen organizing and staffing the 800 number and the processes around that. As soon as the money started to flow, however, that corporation replaced him with a white guy who was the son of a friend of the owner and who lived in Rumford, a wealthy suburb a few miles away. While the process was running with volunteers, all the volunteers came from one of the cities. The moment the money started to flow, the privately held corporation wanted to use that money to bring back their own long-term employees, all of whom lived elsewhere, and it took a pitched battle to make sure that at least some of the people hired were from the cities, spoke the languages, and knew the culture of the places in which we were working. As soon as the money started to flow, the planning process went from almost all volunteer community people, deeply involved in the cities and community, to all white people who barely knew the cities at all—but who were all getting paid.

In a few months, then, the little cities of Central Falls and Pawtucket saw a change from a mostly volunteer, locally initiated, locally run process of public health and self-defense to a poorly funded bureaucratic exercise that allowed state officials to claim they were doing something and that resulted in cash flowing to people who lived outside the community and didn’t really know the cities at all. People organized themselves to protect themselves and their neighbors. But as soon as the state became involved and money started flowing, the focus of the response flipped around. All of a sudden, the Incident Command System of Pawtucket and Central Falls, which had produced a little public health system called “Beat COVID-19” that addressed itself to a pandemic caused by a new disease that was infecting, hospitalizing, and killing too many people, many of whom were poor and working people, had become focused on contracts and cash flow, and most of the now-well paid people who were involved were interested in the contract deliverables, not simply in what the community needed. Large sums of money were being moved about. But the process wasn’t about the common good anymore. Or democracy. Or even about the incidence and prevalence of disease.

That was when a light went off in my brain. I had long understood that health care in the United States is a business, not a service provided for the public good, and that we have a medical services marketplace, not a health care system that cares for all Americans. But this experience let me see health care in a new way. What if health care was more than just a business? What if health care had become a false flag, a Trojan horse, a game of three-card monte? A way to use this pandemic to create income, a way to extract wealth from a community, or, worse, a way for politicians to attract attention to themselves so that they could advance their careers? The pandemic had attracted attention and money. When that money arrived, the smart set—people with one kind of power or another—figured out how to get that attention and money to flow their way. What if communities where the pandemic hit were just the raw materials of this process, the place where the gold is mined, the oil is extracted, the rubber or banana trees are grown, and the people are just the providers of labor and consumers of manufactured goods made elsewhere? What if medicine wasn’t about health or health care or the pursuit of happiness or democracy at all? What if medicine was just colonialism? An excuse to extract the wealth of communities, one that destroys their ability to care for themselves in the process.

In a pandemic, and generally, we think of health care as a public good, a service communities need to be stronger and more resilient. But from research for my previous books, The Nature of Health and Health Care Revolt, I knew that health care in the United States has another function altogether. In the US, health care is a business that tends to make the rich richer and keep the poor impoverished. I learned this by following the money and by seeing who makes how much doing what—by seeing, for example, how hospital, pharmaceutical, and insurance executives and their shareholders make a ton of money while family doctors do okay but have to work all the time, while the nation struggles with income inequality, dropping life expectancy, and downright terrible health outcomes, especially among poor people and people of color.

But in the pandemic, I learned that the US faces a worse problem yet. In the pandemic (and for fifty years before that), people with power and money co-opted federal and state government and used state power to exploit the pandemic to make more money for themselves. The pandemic revealed what had been hidden from Americans in plain sight: that the health care profiteers have turned government into an agent of wealth extraction and have turned medicine itself into the excuse for government to do so. State power has turned healthcare profiteering, objectionable enough in itself, into colonialism—into a process that strips the resources from communities and leaves those communities with no agency and no ability to protect themselves, exactly what the old colonial powers did across the developing world.

Medicine and Colonialism

I had been working part-time at a community health center in Central Falls and Pawtucket, Rhode Island, for the four years just before the pandemic struck. Community health centers were invented in the mid-1960s (by Jack Geiger, MD, a mentor and hero) to help address the health impacts of racism by providing primary health care to the poor, to working people, and to anyone without a family doctor, many of whom are people of color. The community health center’s staff was diverse. Most of the medical assistants, receptionists, and other frontline staff lived in Central Falls and Pawtucket. Some of the nurses did as well. But very few of the doctors, nurse-practitioners, or physician assistants lived in either city, and very few were people of color. None of the more highly paid administrators lived in the community, and none, not even one, were people of color. Too few members of the community health center’s board were actual community members, and too few were people of color, even though by federal regulation, 51 percent of the board had to be “users” of the health center, a regulation the health center satisfied by the letter but not the spirit of the law. To its credit, and with a little pushing from me, the board had added four people of color from within the community, but it was still majority white, even though the main site of the health center itself is in Central Falls, which is 80 percent people of color.

This pattern—that the people who work in healthcare administration and leadership in hospitals and health centers live in other communities—pops up wherever medicine is practiced and wherever hospitals and doctors exist in the US (except, perhaps, in rural parts of the country, where there is no practical way for administrators and doctors to live in other communities).

Take hospitals. The executives of hospitals, their boards, and most of their doctors typically live in wealthy suburbs, while the poor and working people who make up the bulk of their patients live in poor and working communities near the hospital itself.

It’s like that in community hospitals. But the pattern is much more apparent in academic teaching hospitals, which are often located in the midst of urban poverty: hospitals like Mount Sinai Hospital and Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York, Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Yale in New Haven, the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals in Cleveland, Boston Medical Center and Boston University Medical Campus, Rhode Island Hospital in Providence, and Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia (before it was bought and closed by a venture capitalist).

Though not all academic hospitals are in poor urban areas, the number of academic hospitals that are located amidst urban poverty is remarkable. Are those hospitals located in poor places just because poor communities have lots of sick people? Or is there something about academic hospitals that makes or keeps poor places poor? Most poor and sick people have Medicare and Medicaid, which pay for the care of the sick. If we think about Medicare and Medicaid as representing part of the wealth of those poor places—in 2022, they represent between $5,000 and $12,000 or more per person per year in most states—are hospitals stripping away some of that wealth, which could otherwise be spent locally, and carrying it to other places? Could it be that, yes, while those hospitals teach medical students and residents, they also use the cover of illness to extract funds from the federal and state governments and then send those funds elsewhere? Could it be that those hospitals are not just in the business of health care but are also in the business of extracting wealth from the communities in which they are located and moving that wealth elsewhere? Hospitals extracting wealth from communities? Impossible! But if so, that would make hospitals something other than health care or medicine entities. That would make them like the gunboats in the colonialist enterprises of yore, and it would make the whole United States health care mess almost sound like… colonialism.