By

Salut! Live

April 6th, 2023

Here’s one for the media studies class.

How do you get a complimentary piece about a radical leftwing enemy of the capitalist system into a newspaper nicknamed the house journal of the Conservative party? Do you damn with faint praise, patronise with a barely concealed snigger or just press on with lavish admiration and await the flak?

Looking back over my numerous scrapbooks of articles written during a journalistic career slightly closer to 60 years old than 50, and quickly locating a review of one of Leon Rosselson’s albums, I was soon reminded of when I had to ask myself those questions.

In the event, it was not that difficult on The Daily Telegraph of the 1980s.

Then as now, it was a partisan champion of tribal Toryism. Unlike today, however, it had exemplary news pages, reporters striving for accuracy and balance; most of us were leftish, liberal or apolitical in any case and the rightwing rhetoric was for others, those employed to deliver it.

And those responsible for the arts pages were, to a very large extent, left to get on with their work with minimum political interference. Why, otherwise, would they permit anyone to write about folk music, scarcely a genre designed to maintain the status quo, in the first place?

Reviewing his album, I Didn’t Mean It, in 1988, I used somewhat laboured humour to give my thumbs-up:

His great virtue, I suggest, is that his songs could easily entertain a right-wing atomic scientist and part-time spy whose ideal weekend relaxation would be to finish Territorial Army exercises early enough to get to the Royal Albert Hall in time for Elgar

Of course knew as I wrote the sentence that no one matching my fanciful description, indeed very few Telegraph readers at all, would warm for a second to Rosselson’s subversive lyrics, however eloquently constructed. But there wasn’t a hint of rebuke; the review sailed into the paper mostly untouched and one sub-editor told me I had raised a laugh on the arts desk.

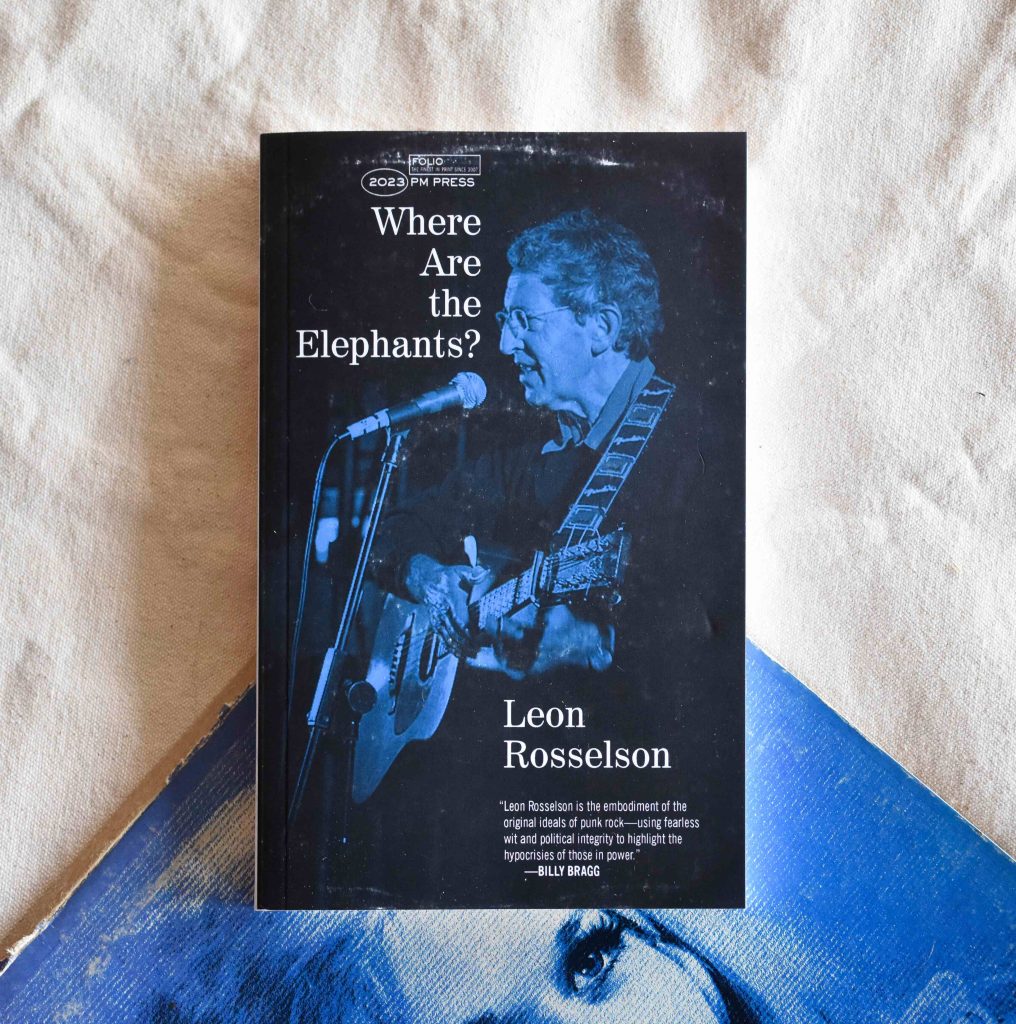

Getting on for 35 years later, I am reading – with immense pleasure – Rosselson’s memoirs, a slim but utterly absorbing volume combining essays and those clever, witty, challenging lyrics. It is called Where Are the Elephants?, a spectacularly useless phrase that appeared in a BBC audio course from which Rosselson learned a little German before attending political song festival in East Germany, then part of the Soviet bloc.

He tucked the translation, Wo Sind die Elefanten? into the recesses of his mind until he was able to use it in a song reflecting mixed feelings about the subsequent fall of the Berlin Wall.

Broadly as sympathetic to the clamour for a freer atmosphere in the Communist world as he was to the Paris spring, protests against the US war in Vietnam and revolutionary Cuba’s resistance in the face of American might and belligerence, Rosselson wrote:

Now the Berlin Wall has crumbled like sand castles in the sea

And there’s been a revolution where there wasn’t meant to be

And I’ve watched the crowds on TV as if waking in the dawn

They see the old world dead, the new world not yet born

And are they bright with hope of videos and dishwashing machines

Big Macs, cosemtics, porno magazines

And Dallas on their television screens?

There, I think, you have it. Rosselson, the son of a Stalin worshipper who never really lost faith, could see the intellectual and human absurdities and cruelty of socialism as practised by Russia and its client states but wasn’t at all sure it was any worse than the consumerism, greed, selfishness and international bullying of the US-led Free World. Elephants in the room of progress towards Utopia.

Where are the Elephants? Published by PM Press in the UK and USA (£15.99/$16.95). Order at this link

Parts of the book, short as it is (giving hope that my own slowly-in-progress novel, struggling to get far beyond 40,000 words, may have legs), are – for me – déjà vu.

The chapter entitled Me, George Brassens and the Last Chance has even appeared on these pages and is a great read.

Rosselson’s impatience with Leonard Cohen, and his rejection of all attempts to equate songwriting with poetry, are are also well known and have been discussed at Salut! Live.

But any collection of essays is likely to include the writer’s past work, whether or not published. It all fits together seamlessly and forms the sort of book you can dip into at will, devour in two or three evenings or tackle – as I have done – in chunks.

Along the way, we hear from snapshots of Rossleson’s life and career. He regrets that unlike in the American labour movement of early decades of the 20th century, among women and children of Soweto and even Vietcong soldiers on their way to battle, song seems to have little place in British socialism and workplace militancy. Joining mass pickets outside the Grunwick film processing laboritories in 1977 London, he was disappointed to hear no singing beyond a rendition by the trade union leader Norman Willis of The Man That Waters the Workers’ Beer, no one joining in.

“A defeated people does not sing,” he writes. “Perhaps the converse is also true – a movement that has no songs is already defeated.” The Grunwick strike ended in failure despite an official inquiry calling for the reinstatement of sacked workers and recognition of their union rights.

In a fascinating chapter devoted to an interview with his fellow singer-activist Robb Johnson, we learn not only of favourite pieces of his own work, from the powerfully evocative My Father’s Jewish World to the anthemic, much-covered The World Turned Upside Down. We also get glimpses of his personal tastes: they include Piaf’s Les Amants d’un Jour [see clip below], early Dylan (A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall) and Dr Hook’s The Cover of Rolling Stone. The unexpected choices should not have shocked Johnson who, 16 years ago, wrote a compelling series for Salut! Live‘s sister site Salut! on his own extraordinary passion for the music of Johnny Hallyday.

Leon Rosselson, now pushing 89 and not in the best of health, and I have never met.

He is clearly way to my left in outlook; what I used to think made me Labour left of centre would now be seen by plenty, even much to his right, as centrist or worse.

But if we were to meet, there’d be plenty to agree on: racism, public sector pay disputes, the scarcely mitigated nastiness of the Tories. I didn’t enthuse as he did about Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour leadership and manifesto but do condemn Keir Starmer’s determination to banish his predecessor from Labour benches. Rosselson, though Jewish, opposes the Israeli state whereas I simply deplore Israeli policy, favouring the only fair option of a two-nation solution.

But songwriters of his calibre are to be encouraged and acclaimed. They are necessary. There may indeed be a better way of running the world, yes the western world, than the the dull norm of alternating mainstream right and left, the differences often wafer thin.

I find idealism but no viable answers in Rosselson’s writing, in essay or song form. But whether or not it knows it, and we can safely assume that it does not, the world is a better place for its presence.