By Mike Phipps

LaborHub

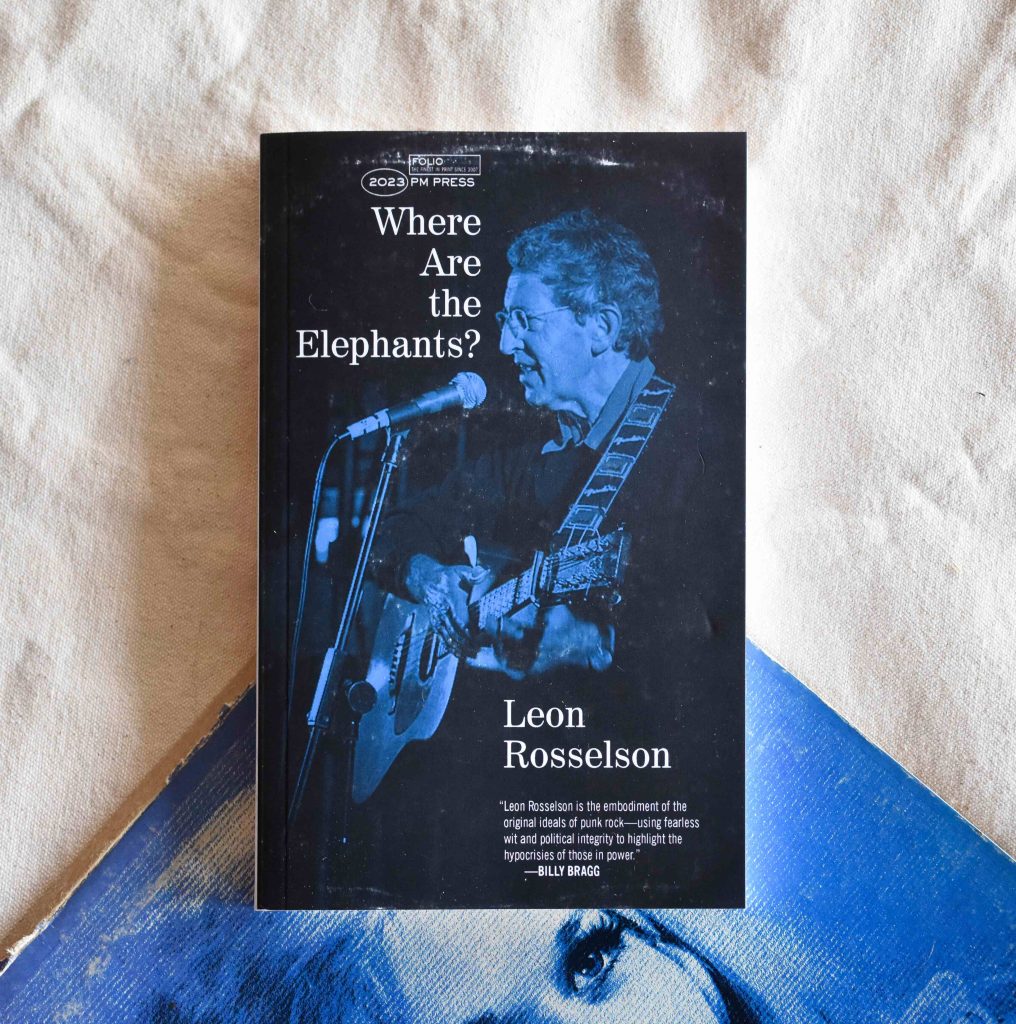

It would not be hyperbolic to describe Leon Rosselson as a living legend. He has been writing songs for over 60 years and some of them, such as The World Turned Upside Down, are familiar to a wide audience.

I heard many of his songs sung in clubs long before I saw Leon Rosselson play live. His work was also performed on TV in the early 1960s in the satirical show That Was The Week That Was. As well as producing several songbooks of his work, Rosselson has published 17 children’s books. He was a central part of the folk revival and his work is usually subversive and socialist and often humorous.

But not always humorous. Palaces of Gold, his song about the Aberfan mining disaster of 1966 when a slag heap collapsed engulfing a Welsh village school, killing 116 children and 28 adults, is breath-taking in its cold anger. Likewise his powerful telling of the sharply observed human stories behind people forced to migrate from their homelands in The Wall That Stand Between.

Where Are the Elephants? mixes autobiography and polemic and draws on his experience as an engaged artist and political activist. It begins with a memory from the young Rosselson’s seventh birthday in June 1941, which coincided with the invasion by Nazi Germany of the Soviet Union, of which Leon’s father was a fervent supporter. When in 1950, Leon tries to run as a Communist – mainly in the interests of political pluralism – in his school’s mock election, the headmaster bans his candidacy – “my first lesson in democracy.”

Rosselson’s doubts about the Soviet Union grew, particularly after its invasion of Hungary in 1956, but he was also glad it existed as a counterweight to the power of US imperialism. He was hugely impressed by Aneurin Bevan’s oratory when he spoke at the end of the great demonstration against the Suez War in 1956 – only to have his illusions shattered a year later by Bevan’s attack on the policy of unilateral nuclear disarmament.

He began writing songs and singing on CND marches. He even wrote an entire musical about nuclear disarmament for the West End stage but it was never produced.

Rosselson was dissatisfied with the gradual reforms of the 1964 Labour government and wanted a genuinely alternative society. But he was also sceptical of – perhaps too old for? – the late sixties counter-culture, preferring the weightier critiques of capitalist consumerism provided by Herbert Marcuse, RD Laing and Rachel Carson. The problem was: “If this was a revolution in the making, where was the working class?”

It was a theme he would return to repeatedly, given the political defeats suffered in the era of neoliberalism. After the 2008 financial crash, he wrote a song that began:

Robespierre is wagging his finger

Karl Marx is scratching his head

They ought to be shooting the bankers

But they’re giving them money instead.

The plebs should be storming the ramparts

And whetting the guillotine’s blade

Singing capitalism’s in crisis

So where are the barricades?

Rosselson loathed the dominant culture of the Thatcher years, but there were lighter moments. In 1987, Peter Wright’s book Spycatcher, which spilt the beans about the murky deeds of MI5, was banned by the courts from being published in Britain or quoted in the media. “This outrageous censorship prompted the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom to ask me to encapsulate the book in a song whose illegality would show up the absurdity of the ban,” writes Rosselson. “I stayed up half the night trying to digest its somewhat turgid prose and the next day managed to roll as much of the book as possible, including a couple of direct quotations, into a song, Ballad of a Spycatcher.”

Despite its publication in the New Statesman, being made into a single by Billy Bragg and the Oyster Band and getting Radio 1 airplay, Rosselson failed to get arrested. The song did reach number five in the indie singles charts, however.

This book is less a standard autobiography and more a collection of ideas and observations. Some of these are nonetheless powerful, for example, this comment on the Bush-Blair war on Iraq:

“The demonstration against the Iraq War on 15 February 2003 was the biggest I have ever been in… A million of us, according to estimates, surged past the Houses of Parliament, shouting our opposition to the impending attack on Iraq and the lies used to justify it. Similar demonstrations were taking place in cities across the world. Surely they would listen. And then the political classes, in their gutlessness, their stupidity, their gullibility, their cynicism, their inhumanity, voted for war. So much for democracy.”

Later, in a song, he wrote of Tony Blair:

And did the slaughter his war brought

Ever give him pause for thought?

And did the chaos he created

A country smashed and devastated

The tortured, the incarcerated

The shattered millions who fled

The maimed, the half a million dead

Cause him to doubt or hesitate?

Or did he simply calculate

That this was a price that was worth paying

And salved his conscience by praying?

Well, afterwards, you couldn’t get

From Blair a smidgeon of regret.

Indeed this unrepentant man

Declared a wish to bomb Iran.

This liar, fantasist, and faker

Will answer only to his maker.

Now think on this—for all his crimes

We elected Blair three times.

In one section, Rosselson reflects on the absence of a tradition of singing, in England especially, within the labour movement, which is not the case in the US or elsewhere.

“In Soweto, women and children sang as they were shot down by the police. The Viet Cong carried song sheets into battle with them. Civil rights demonstrators in the States sang as they were being attacked by Alsatian dogs, fire hoses, and billy clubs because it made them feel less alone, less afraid. The importance of the New Song movement in Chile can be gauged by the lengths the junta went to destroy it.”

But equally he is dismissive of the notion that music should be a political weapon for mobilising – or manipulating? – the working class. In any event, the power of music in politics, he argues, is limited to cementing, rather than changing, people’s beliefs.

I’m not so sure. Perhaps powerful songs can open people’s minds to radically new ideas. Rosselson plays down the influence of Rock Against Racism and indeed of rock music in general, but I found his viewpoint on this a bit dogmatic.

As an anti-Zionist Jew, Rosselson is unafraid to speak his mind. “Why is there a Labour Friends of Israel?” he asks. “There isn’t a Labour Friends of Myanmar. There was never a Labour Friends of apartheid South Africa. Why Israel?”

The book ends with an audience with Robb Johnson about the art of song-writing and performing. Johnson himself is an intensely political songwriter who has released more than 40 albums since the mid-eighties and performed live with Rosselson on many occasions. The book is an engaging read, but better still are the songs: buy the records, hear the performances.