The Quietus

March 18th, 2023

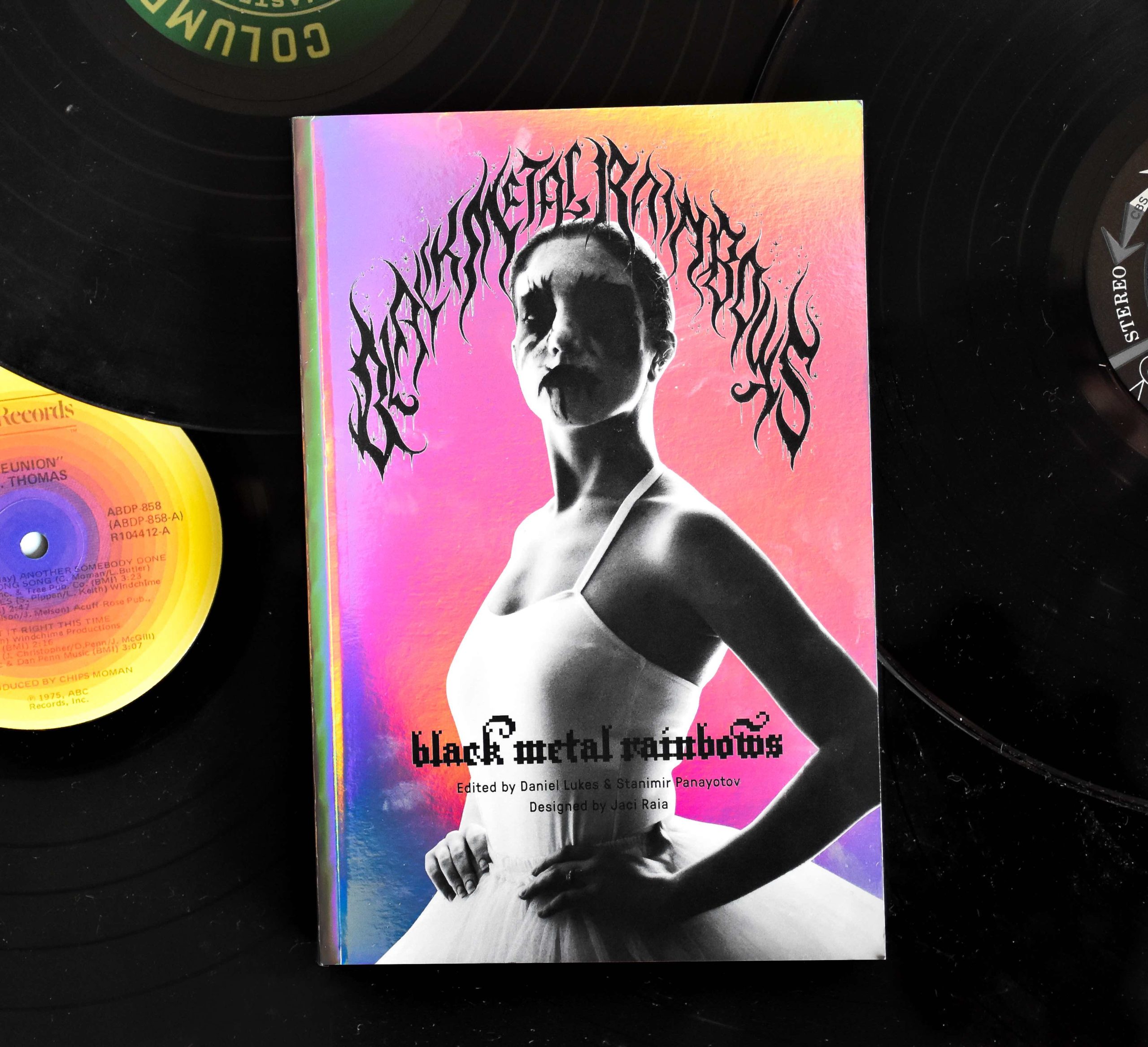

In an exclusive extract from the new book Black Metal Rainbows, writer and musician Margaret Killjoy insists you don’t win a culture war by giving up ground

Sometime around fifteen years ago, I got on a bus in Amsterdam to go to Rotterdam to try to fight Nazis. I’m not much of a street fighter, let’s be honest. These days especially, I’m more of an anti-fascist cheerleader than anything else, so I milk this story for all the street cred it’s worth. But it happened, and it’s relevant, so I’m going to tell it.

Some Nazis in Rotterdam had burned down a mosque. When the community tried to rebuild, Nazis threatened to stop them. So antifascists from all over the country got on buses to head over there and defend the mosque.

My bus didn’t make it. The Dutch police arrested every anti-fascist they could find before we even reached the city, and when we got there, they made our bus driver drive the lot of us to jail. Everyone on the bus, none of whom I knew, wanted to protect me, because I was a foreigner. All of them pretended they weren’t Dutch, that they only spoke English. Four of them went to foreign detention with me and only admitted their own nationality when I was being released.

Those anti-fascists were and are some of the bravest people I’ve ever met. They weren’t particularly kind, or caring, or empathic… no more or less so than anyone else. They defended me from the state for the same reason they defended Muslims from Nazis, because they were antifascists, committed to fighting against systems of oppression.

Oh, and those anti-fascists, an awful lot of them were skinheads.

Skinhead culture started as a multiracial working-class subculture, and a lot of skinheads, maybe most of them, refuse to let Nazis take that away from them.‹› ‹› ‹›

A friend of mine, she’s this tiny woman who spends her days hating everyone, scowling, listening to black metal, worshipping the old gods, and getting Norse pagan symbols tattooed on her body. She also writes poetry. She also tracks fascist activity. When the Nazis came to her town to parade around in their swastikas, she got in her truck and drove all over the city. Not to fight Nazis, not necessarily. To look for anyone who needed rides away from danger.

She won’t let Nazis have her subculture, her heritage, or her religion.

She’s one of my heroes.‹› ‹› ‹›

Black metal is a politically contested space. There’s a wide swath of leftist and anarchist bands and fans. There are, quite famously, more than a few Nazis. Of course, most of the fans and bands aren’t particularly politically engaged in one way or the other and are just into grim, extreme, beautiful music.

I’m an anarchist and an anti-fascist, and my problem isn’t with Nazis playing shows, it’s with Nazis breathing air into their lungs. But I understand why they’re attracted to the genre.

Mimi Chrzanowski,Mother Knows Best, 2019, ink on paper, courtesy of the artist

Mimi Chrzanowski,Mother Knows Best, 2019, ink on paper, courtesy of the artist

Even though fascism, perhaps the clearest example of an authoritarian ideology ever created, is the polar opposite of anarchism, I understand why we’re both drawn to drink from the same dark pool. A musical subculture is also an aesthetic culture. We make music – and visual art and fashion – to aesthetically express certain ideas. There are plenty ideas to choose from in black metal. The wild, chaotic, dark beauty of nature. The wars we fight against society. Isolation and grief and loss. The acceptance of, and revelling in, our mortality. The old gods, or Satan, or whatever spirits we draw power from.

Anarchists have reasons to romanticise those ideas. So do fascists. It’s dangerous shit to romanticise ideas that Nazis might romanticise as well. We have to be careful, be alert. But what we can’t do is abandon these ideas, this cultural and aesthetic terrain, to fascists. We have to fight. Both sides of an ancient battle might worship a god of war. They might even worship the same god of war. But that doesn’t mean either side is wrong to do so. We venerate gods, or concepts, to draw courage from them – to draw power.

Holding on to aesthetic and cultural terrain gives us power.

There is a cultural war raging around us. There are literal wars, and there are also political wars, but the cultural war matters too. Fascists have consciously engaged in this war for some time now. As I’ve heard from harder-working antifascists than I, a while back some Nazis realized they weren’t getting anywhere with swastikas and shouting, so they started to work “apolitically.” Specifically, they decided they wanted to promote cultural values that lend themselves to the Nazi agenda. Some of those values are reasonably obvious red flags: nationalism, blood-and-soil, anti-multiculturalism. Some of those values are far more complex: glory, honour, loyalty, the reverence of family.

As an anarchist, I prefer to wear my heart and my politics on my sleeve. I have no desire to trick anyone into being an anarchist. I don’t believe my values should be the values shared by everyone in the world. I don’t believe in my own ideological supremacy. I only believe in my own personal autonomy. When I work to share cultural values, I want people to know where I’m coming from, so they can make up their own mind about whether or not I’m to be trusted. To me, this is one of the cornerstones of anti-authoritarian cultural work.

Yet I sometimes find myself promoting somewhat similar cultural values as fascists. I need to be careful when I do that. Take the idea of loyalty. I don’t believe in loyalty, not as such. I believe in solidarity, instead. These are comparable social values, but the difference matters. Loyalty, as I understand it, is about allegiance. Allegiance is about the subordination of one to another. Loyalty happens, by and large, in a hierarchical fashion. Solidarity is performed between equals.

I also hate quibbling over semantics, and there are plenty of people who use the word loyalty without regards to hierarchy. Or people who see their loyalty as themselves acting subordinately to a certain value. Loyalty to one’s family or friends, for example, might be the loyalty an individual shows the larger social body. That’s not how I’d prefer to describe things, but I don’t have a problem with people who do.

The idea of the individual showing loyalty to the larger social body isn’t very black metal, of course. Black metal seems to me to be far more often concerned with the war of the individual against society than one’s subservience to it. Frankly, black metal always feels like an odd thing for Nazis to be obsessed with, beyond a youthful rebellion and a general bloodlust. Fifteen years ago, at least Scandinavian black metal Nazis were the laughingstock of the Nazi world, and that makes sense to me.‹› ‹› ‹›

Black metal has long concerned itself with trying to be evil, whatever the fuck evil means. There might not be any other concepts in the world as subjective as the concepts of good and evil. Most of the time, the idea of good roughly means aligned with the individual’s or community’s moral values, and evil means everything that isn’t.

I don’t know if I’m evil. Depends on who’s labelling me. Anarchists have always been painted as evil by governments and capitalists, but our genocide count is a hell of a lot lower than that of pretty much every other political ideology anyone has tried out in the past five hundred years. I don’t actually think anarchists are very evil. I think authority has a better claim to that word.

Personally, I’m drawn to revel in a separate but comparable concept: monstrosity. I can’t find the quote anymore, buried in the endless expanse of the internet, but I once read another trans woman’s post about metal. If I recall correctly, she’d basically been called a poser after talking shit about some white cis dude for wearing a Nazi black metal shirt. She said, and I paraphrase, “I am a trans woman. I inject the concentrated urine of mares to become something monstrous to society. I am more metal than you will ever be.”

Ezra Rose, Minerva Metalhead, 2019, pen and ink with collaged vintage doll ad, 23 x 30.5 cm, courtesy of the artist

Ezra Rose, Minerva Metalhead, 2019, pen and ink with collaged vintage doll ad, 23 x 30.5 cm, courtesy of the artist

I don’t know whether or not I’m a monster. That decision is up to society.

I do know that being a monster is very, very metal.‹› ‹› ‹›

Fascism isn’t the only thing I’m trying to destroy, of course, and anti-fascism isn’t the only thing I’m trying to hold space for in the black metal scene.

I want to destroy patriarchy too. I’m not trying to destroy men – well, not most of them – but I have every desire to drive the forces of male domination back into the abyss from which they crawled.

I never want to go to a show only to find out that the singer advocates the holocaust of ethnic minorities. I also never want to go to a show to find out that the singer is unrepentantly a rapist. I never want to overhear racial epithets aimed at minorities. I also don’t want to overhear some group of men complaining about sluts or the friend zone. I don’t want some cis dude to fucking put his hand on the small of my back as he passes in the crowd. I don’t want to play shows for all-male audiences, to keep sharing the stage with only men.

I’m fighting for cultural space as an anti-fascist, but I’m also fighting for cultural space as a woman. I started my band Feminazgûl partly to do that.

I named the first EP The Age of Men Is Over quite explicitly to do that. I’d been listening to black metal for ten or fifteen years. One depressed winter while getting over my sweetheart deciding she was too straight to date a girl after all, I threw together twenty minutes of bedroom-produced black metal. I just needed a way to get out some feminist angst.

I never expected anything like the response I got.

As a trans girl, I’m always afraid of taking up space in feminist circles. Afraid that I’ll be rejected by other women. That didn’t happen. Quite the opposite. One woman reposted the album saying she was going to listen to it when she went into labour.

What caught me off guard but shouldn’t have is the overwhelming support we (Feminazgûl is now a two-piece) have gotten from cis men. A lot of men are nearly as sick of black metal being a boy’s club as women are. Men are realising that patriarchy forces them into shitty, painful boxes and isolates them from half the world. We’re winning the cultural war.

There’s a downside to all our advances on the cultural front, unfortunately. We’ve made enormous strides in the past decade in LGBTIQ+ acceptance. As far as I can tell from my position as a white person, it appears that larger chunks of society are making some progress against racism, as more people look at power systemically and understand that white supremacy and colonialism are problems we can’t just fix by “treating everyone equal” like my parents’ generation tried to tell us. We have gay marriage and an awareness that “reverse racism” is no more real than the tooth fairy. There’s a whole generation of Americans that are no longer afraid to criticise capitalism and to call themselves socialists or anarchists. We care about the freedom and autonomy of sex workers. Trans people are coming out of the closet left and right, and some of us even dare to piss in public restrooms or read books to children.

All of this freaked the right-wing the fuck out, and they’re in the process of making one last, desperate grab at power. The far right has always been terrible at creating and shaping culture, but, unfortunately, they’re pretty good at political power, so they’re taking it, as fast as they can, and a lot of our hard work is slipping away from us – fast. It’s a last-ditch effort, but it’s not necessarily a death knell. We have to keep fighting.

The cultural war isn’t the only war. Aesthetic ideas and subcultures aren’t the only thing we can’t cede to fascists.

Some of the fights are a lot more physical.

Myself, I just want to make music, write books, and live my queer life here in Appalachia. But I can’t. Fascism is ascendant politically, even while liberation is on the rise culturally. So I have to fight. I also can’t sit back and just live my life, because the local Nazis are stalking me. They send me e-mails, telling me what car I drive, telling me where I hang out.

The local Nazis do a lot of things but playing black metal worth a damn ain’t one of those things.

Scare me ain’t one of those things either.

Black Metal Rainbowsm, edited by Daniel Lukes & Stanimir Panayotov, is published by PM Press