By Evan Robins

Trent Arthur

March 9th, 2023

Disclaimer: CUST, much like Trent University and Peterborough as a whole, is an incestuous little community, and it would be folly to pretend I bring no bias into this article. For purposes of disclosure, I am currently a student of Dr. Hodges, though everything that follows constitutes my own opinion and not an attempt to ingratiate myself to any members of Cultural Studies faculty for my own academic benefit.

Dr. Hugh Hodges and his book “The Fascist Groove Thing” imposed against the Union Flag. Graphic by Evan Robins

Students, Faculty, and community members poured into Bagnani Hall by the dozen on the night of March 1st. The fastidious colleague who accompanied me lost track of exactly how many somewhere past the sixty mark. I told him not to worry about it.

“Dozens,” I declared. “For any number of people above twenty and less than several hundred, I always just say ‘dozens’.”

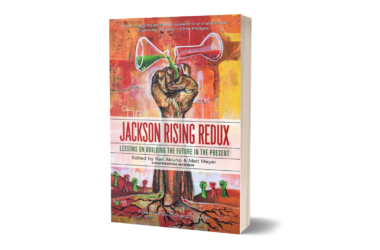

The occasion for drawing said dozens of attendees? None other than the long-awaited launch of Dr. Hugh Hodges’ The Fascist Groove Thing: A History of Thatcher’s Britain in 21 Mixtapes. While I can’t speak to its wider cultural anticipation, the book had certainly been the talk of the Cultural Studies undergraduate population for some time. Indeed, a great number of my classmates showed up eagerly for the book launch. After all, who’d want to miss Hodges—both a charismatic lecturer and an amiable, down-to-earth seminar instructor—writing a lengthy piece of non-fiction with a novel framing device? This represented in mine and many others’ minds an accessible, profound, and above all, interesting treatise with the opportunity to appeal to people beyond those who do it for the love of the game.

The book itself comprises seven parts, each prefaced with a complete mixtape curated by Hodges himself—and not including the foreword, coda, Works Cited, section “For Further Reading,” and the complete discography provided for the reading seeking to broaden their musical horizons. Throughout, Hodges, who currently teaches a class on Music & Politics in collaboration with Dr. Ihor Junyk, sketches a musical portrait of Thatcher-era Britain, discussing at length austerity, labour action, and the cultural climate of the 1980s through this inspired approach.

On the night of the launch proper, I’d yet to get my hands on the book, as online pre-orders were only being fulfilled Friday. Had I had cash on hand, I’d probably have procured a second copy then and there (just that excited was I). Instead, resolved to (in the words of a steadfast Arthur comrade) “raw-dog” the whole affair, I took a seat with my notebook and trusty fountain pen, poised to hastily scribble anything of note to come.

Dr. Michael Eamon, Principal of Catherine Parr Traill College and Professor of Canadian Studies, introduced the proceedings with a few words welcoming attendees to “this great college, this auspicious event.” After a brief land acknowledgement recounting Trent University’s inception on the site of what is now Traill college, Traill’s historical role as a women’s college and vessel for women’s empowerment in academic spaces, and the college’s position on the route of the Chemong portage. Following Dr. Eamon’s introduction, Dr. Michael Epp of English and Cultural Studies—whose research interests fittingly include “public and political violence,” and “Irish Republicanism,” both staples of the Thatcher years—expressed his pleasure to introduce his “friend, colleague, and bandmate,” Dr. Hugh Hodges.

Finally taking the stage, Dr. Hodges spoke briefly about the process of writing the book, his joy at its publication, and offered many sincere thanks to his colleagues and family. He spoke briefly about the foreword of the book—written by Dick Lucas, vocalist of the anarcho-punk band Subhumans—and the heartfelt coda from Chumbawamba’s Boff Whaley. Hodges also thanked the students and volunteers setting up the lecture hall, manning the book table, and making sure everything ran according to plan, his publishing company—independent, radical outfit PM Press—as well as Trent Radio, who were on-site recording the event for public broadcast.

“Evangeline, where are you?” he asked in the midst of his media acknowledgements. “You’re here, yes? You’re covering this?” After I shyly raised my hand and offered a confirmatory “yeah”, he clapped gleefully and declared: “Thank you in advance to Arthur!”

“So what I’m going to do this evening, is possibly put my reading glasses on, and take them off again,” Hodges chuckled, squinting at his notes as he prepared to present a selection from his book. Speaking with animated eagerness, Hodges pointed to the screen which displayed a high-definition photo of Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bollocks: Here’s the Sex Pistols. “I’ve always enjoyed telling people,” he announced. “And I think this is true—that the first album I bought, when I was eleven-and-a-half years old, was Never Mind the Bollocks.” This he said, speaks to his punk credentials, and both his inspiration and the position from which he writes The Fascist Groove Thing. Seconds later though, Hodges confessed that the second album he ever bought was in fact British novelty folk group The Wurzels’ Scrumptious!. “I may not have been the most musically discriminating eleven-and-a-half-year-old,” he admitted.

Still, the Wurzel’s and their 1976-smash hit “The Combine Harvester” proves a rather fitting point of entry, as Hodges chose “Mixtape 2: Do Not Push Pineapple” from Part 1, “Everything’s Brilliant!” for the night’s reading. The chapter is an introductory deep-dive into the profoundly British phenomenon of novelty songs, and particularly, their pop-cultural ubiquity and chart domination. Hodges writes, “if this book were a properly balanced account of what the British public actually listened to, much of it would have to be given over to [novelty songs], because, throughout the 1980’s, the public’s appetite for songs by rodents and cartoon characters was voracious, ludicrous, and seemingly insatiable.”

When Hodges tried to demonstrate a few such examples to those assembled, however, things went somewhat awry. “What fresh hell is this?” Hodges asked, prompting an amiable laugh from the crowd. “That is very disappointing, but almost inevitable,” he noted, as music blared through the Bagnani speaker system whilst the projector remained uncooperative. “I’m just going to assume if I keep going it’ll be okay.”

Go on Hodges did, offering countless more examples of this most British phenomenon, all while effortlessly animating his vivid, often conversational prose. At the time, having not got my hands on a book yet, I assumed this might well have been a virtue of adaptation, though in print, The Fascist Groove Thing proves imminently readable, capturing the entrancing, affable conversationalist of Hodge’s impressive oration.

As for the subject of this particular address, Hodge’s ruminations on the oddity that is the novelty song led him to conclude that these particular musical artefacts are testament to a desire within the Thatcherite British public to “just not be grown-ups anymore.” “If you wrap your head around this,” he says, “you’ve gone a long way to understanding British popular music and, by extension, the English.” Hodges further introduced the crowd to “a little theory of [his]—that the British use the charts to torment each other.” “The British love throwing horrible, unlistenable things into the top 10, and then challenging each other to see who will blink first.”

With a conclusion of sorts duly reached, Hodges turned proceedings back on the eager crowd. “Rather than answer questions,” he said, “I think I’ll ask you some things.” What followed was a lightning round of British musicological trivia, though despite mine muttering every answer quite correctly under my breath to my accompanying co-worker, I deemed it best to not compromise my journalistic objectivity even if it was for a pack of Curly Wurlys.

Icaught up with Dr. Hodges shortly thereafter to ask a few questions about the book, and to do a bit of what we in the industry call “Networking”. While the rest of what happens between CUST faculty over drinks is best left unsaid (“What Happens in Scott House”, etc.), Dr. Hodges offered a few valuable insights into the background of the book.

“I don’t make a lot of value judgements [in The Fascist Groove Thing], not because I don’t have opinions about the music itself, but rather because they all contribute something to the narrative,” he told Arthur. “The point of the project is the violence, the sheer polyphonic noise of thousands of voices raised in protest.” When asked where he got the idea, Dr. Hodges chuckled, and ruefully admitted “I was listening to a podcast, and [one of the hosts] said that growing up and coming into his political identity, he wasn’t a socialist, but a ‘Clashist’.” This, Hodges said, resonated with him, “because at one point, literally everything I knew about the Spanish Civil War was from The Clash’s ‘Spanish Bombs’.” He pondered this for a second, before thoughtfully saying: “a rock song can become part of your political DNA through sheer force of poetry.”

The Fascist Groove Thing therefore proves a karyotype, not just of Hodges’ political project but of the political genome of Britain itself at a particularly volatile point in history. Each constituent mixtape tackles some element of this cultural tapestry, together forming a picture of Thatcher’s Britain more complex (and arguably more accurate) than many of the works Hodges himself cites. Despite its gravity, this volume remains effortlessly readable and thoroughly entrancing to music lovers, politics nerds, Cultural Studies students, and history buffs alike. While Heaven 17’s resounding declaration from which Hodges borrows his title still today holds true, we do need The Fascist Groove Thing for all the insights it affords—not to mention a great soundtrack along with it.