The origins of the trans panic

By Scott Branson

Baffler

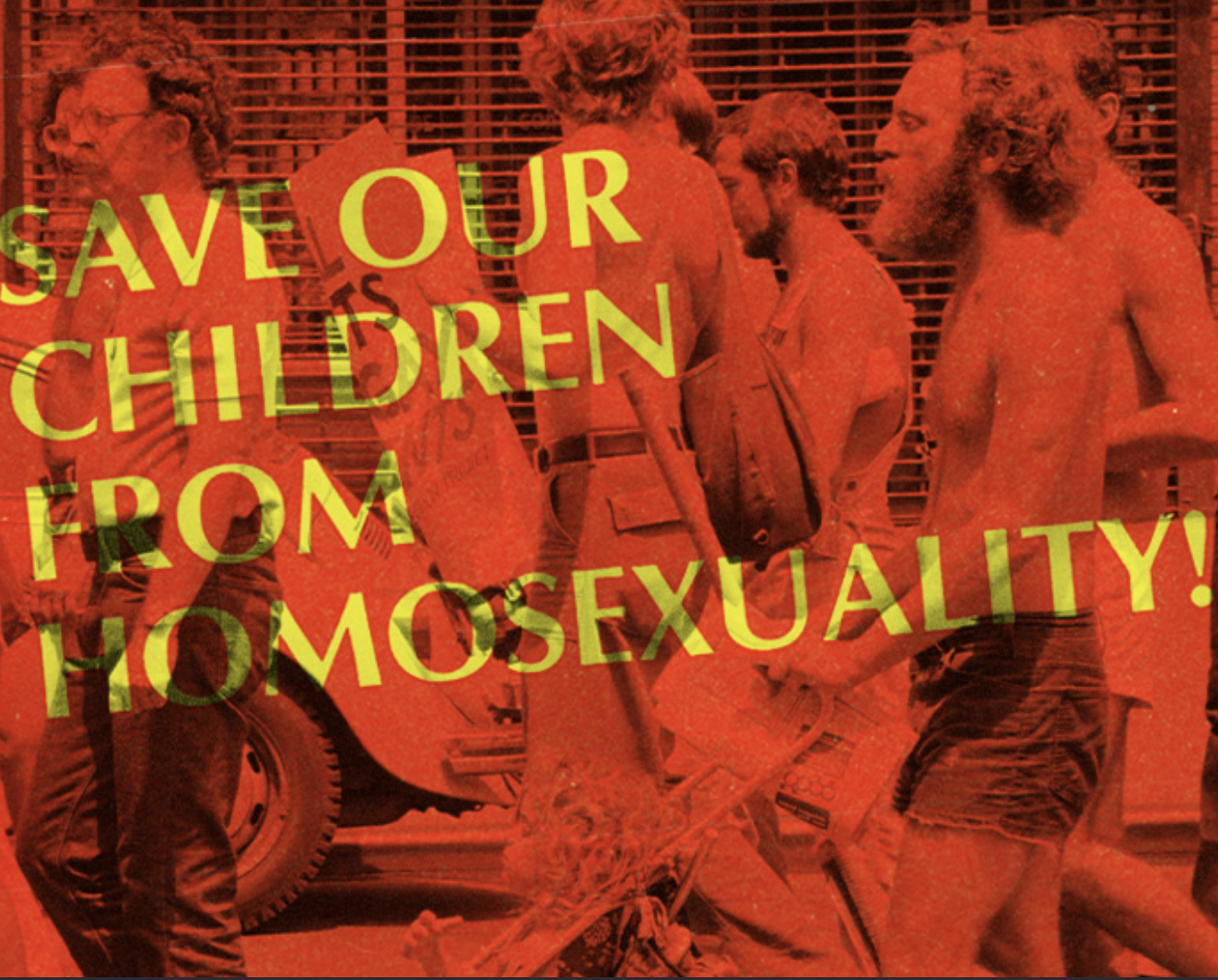

Photo: Gay rights demonstration at the Democratic National Convention, New York City, 1976. | The Baffler

To hear Guy Hocquenghem’s thoughts on the matter, the gay liberation movement exhausted itself almost immediately simply by announcing itself as such. With the confession “I’m gay,” which Hocquenghem declared of himself in the pages of Le Nouvel Observateur in 1972, followed a demand for equal rights under the state, commencing a process of normalization—not liberation but liberalization. We have heard the story of this capitulation ad infinitum, less so its unintended consequences, namely, as Hocquenghem saw it, the further marginalization of others formerly under the umbrella of homosexuality—the trans woman, the effeminate man, the criminal queer, the pederast.

A combination of forces led to this outcome. On the one hand, a “liberated” sexuality becomes legible—strapped to the psychoanalyst’s chair, individuated by sexologists, given an origin. On the other, Hocquenghem points to the moment when the movements “become strong enough to originate new repressions”: the old truism of the sinking ship where you cut off hands of those who cling to you to save yourself. “When homosexuality confesses itself and rationalizes itself,” he writes in La dérive homosexuelle, “it tends to push back into the shadows its old underworld companions.” (All translations my own.)

Fundamental to this banishing from what Hocquenghem called the “republic of sex,” though, is an underlying concept of individuality, property, and control that plays out in the figure of the child. Lee Edelman’s idea of reproductive futurism describes the way political discourse attaches the idea of a better future onto the figure of the child as an alibi for reproducing the miserable conditions of the present, summed up in the vapid political question: “What about the children?”

While Edelman’s famous argument positions queerness as a disruption of the social order whose future is a replay of the past, I want to argue that the gay movement, in its wager of inclusion, in fact helped create that very image of the child, rather than to challenge it. This has come to a head in the reactionary right’s obsession with the transgender child, who actually figures a different future.

One part of the story of gay liberation’s failure can be seen in its parallel development alongside the women’s movement, which helps illustrate how an apparent aim for liberation ends up feeding the power of the state. In France, for example, the Front Homosexuel d’Action Révolutionnaire started in 1971 as a lesbian-led group inspired by the Mouvement pour la Libération des Femmes. Within a few years, though, the group fractured over disagreements about sex: the lesbians were frustrated that the gay men had turned meetings into a cruising ground, while the men thought the women too moralistic about sex. But beyond this, Hocquenghem felt that the gay movement quickly refashioned itself into an “equal” response to feminism, a masculine liberation in other words, defined by an uncritical and unbridled passion for macho masculinity.

Indeed, the trans child does pose a serious threat to the existing social order.

In a sleight of hand, both movements ended up chasing the trappings of traditional gender—a separation of sexes that actually works quite well for the state. Hocquenghem notes that the political longevity of both the gay and women’s movement, in the United States in particular, arises from their claim to the right to privacy, which, as Hocquenghem writes, “tends to become an immense system of compensations between subgroups, defined by the risks that they run and the ones they make others risk.” In other words, through these movements’ ultimate willingness to broker with the sources of power for inclusion, we gain a liberalization of sexuality in deed—and a piecemeal extension of the law’s protection to specific groups defined by the extralegal norms of race, gender, class, migrant status, etc. The laws become inclusive of this new protected group, who get to model themselves on the norms of the white bourgeois family, while the trans woman, the folle or effeminate man, sex workers, other criminals, the unhoused, and pederasts are pushed further to the margins.

From our current vantage point, amid a resurgent pedophilia panic, when we look back at the early years of the gay liberation movement, we inevitably confront the figure of the pederast. The history of sex between men is replete with intergenerational contact, as well as contact across other lines of differences unevenly punished like class and race, that largely gets swept under the rug. Prior to the 1980s the “boy lover” was considered a sexual type, albeit even then one that pushed the bounds of the acceptable—at least in terms of explicitly stated beliefs, if not in terms of actions, whether straight or gay, as evidenced by the “sex tourism” industry. Across the modern era, the Greek history of pederasty has been invoked to champion the relationships of older men with typically older teenaged boys, perhaps most famously by Oscar Wilde during his trials.

In France, the legal fight for gays focused on decriminalizing sodomy and lowering the age of consent for homosexual acts to match the age of consent for heterosexual acts. Strident defenders of pederasty and pedophilia took up this mantle as well, arguing that gay and youth liberation went hand in hand. In the United States, the North American Man Boy Love Association formed in the late 1970s along similar lines and organized against age of consent laws; for a while it had the support of many notable queers. One of the difficulties we face now is distinguishing between the empowerment of youth self-determination and the defense of predatory adults.

By the end of the decade, though, an all-out moral panic around pedophilia came to dominate the media on both sides of the Atlantic, which cast all gay men as perverts and gave birth to axioms like “stranger danger”—conveniently eliding the fact that most child sex abuse happens within cis-heterosexual families, which do not bear the same scrutiny. See, for instance, Anita Bryant’s anti-gay campaign, “Save Our Children”—begun in 1977 after Florida’s Dade County included sexual orientation in its discrimination policies for employment and housing—which equated homosexuality and child predation. Of course, the AIDS epidemic only contributed to the inflammation of violent anti-gay rhetoric. In response, by the 1990s the gay movement narrowed its goals to claims on the property rights bestowed by the family structure, leaving the historical legacy around pederasty unsatisfactorily resolved. The contemporary right’s obsession with “grooming” and transgender children is heir to this legacy.

Though the gay movement and the women’s movement early on touted family abolition, seeing the family as the laboratory of oppression, they ended up splitting: gay men retained a macho commitment that left women behind, while some sects of the women’s movement doubled down on historically coerced roles like motherhood, such that “protecting” children became a feminist cry. As Gayle Rubin details in “Thinking Sex,” certain feminists also began making common cause with Christian reactionaries in the form of the moral panics of the 1980s to stop porn and sex work, while also turning to the police for solutions to endemic sexual violence.

Amid all this furor, one might be excused for not noticing that at the same time, the trans woman was largely expelled from the gay and women’s movement—an expulsion whose fruit is truly ripening in this moment. In the U.S. context, we need only look at the now-famous moment when Sylvia Rivera battled her way on stage at the 1973 Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally to condemn the cisgender white gays for leaving behind the incarcerated and unhoused queers. Under a torrent of boos, Rivera invoked the criminal connotations of queerness—linking houselessness, sex work, and transsexuality—all unpalatable to those seeking a seat at the table:

I’ve been trying to get up here all day for your gay brothers and your gay sisters in jail that write me every motherfucking week y’all don’t do a goddamn thing for them! . . . I have been beaten, I have had my nose broken, I have been thrown in jail, I have lost my job, I have lost my apartment, for gay liberation. And you all treat me this way? . . . The people that are trying to do something for all of us and not men and women that belong to the white middle class, white club!

It’s important that she announces the site of the prison as the demand for gay liberation, and also for the possibility of forms of kinship, envisioning a broader solidarity than the respectable gays would embrace. As Jules Gill-Peterson points out in her important book, Histories of the Transgender Child, Sylvia Rivera, along with Marsha P. Johnson—both to some extent reclaimed and tamed by a corporate gay movement—can point us to an alternative history of trans youth. From 1970 to 1971, they operated Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) House, which helped give shelter and care for trans youth who otherwise would have been on the streets. Through this work, they embodied family abolition and youth liberation, suggesting, as Gill-Peterson writes, that “black trans and trans of color futures . . . do not reiterate the exhausted closure of humanism” and refuse the reproduction of the same. STAR House offered an alternative to the nuclear family and centered the needs of the kids. Even after STAR, Rivera, who died in 2002, still acted as a mother to unhoused trans kids.

Groups like STAR enabled trans futures, while anti-trans groups and legislators today seek to end the possibility of transition over fears of the danger it poses—and, indeed, the trans child does pose a serious threat to the existing social order. If children are used to explain our adult selves to ourselves, then we can see that the particular threat posed, as with trans people in general, is the possibility of transformation—or one could say, of transition. As Hocquenghem might say, it’s the unpredictable flux of desire that ultimately challenges systems of control. We can frame this through the question of social reproduction: the typically unpaid, feminized labor that makes capitalist exploitation possible—not simply in terms of the care of children and workers but also in the formation and maintenance of sexed and gendered individuals. This labor is worked out on the body of children by means of discipline and education. If it works, we get a cis-straight factory line. But of course it doesn’t always work.

If we want to reduce all of this to the most trite and familiar question, a kind of return to the drama of coming out, we come back to the question often asked by the straight world, a question much lamented by gays themselves: What “makes” someone queer? I don’t mean it biologically or genetically—as in the joking title of a FHAR text penned by Hocquenghem, “Where is my chromosome?” I might instead ask how are queer people socially reproduced?

Gender is a form of discipline, the outcome of violence, both historical and contemporary, no matter the form it takes.

Early gay liberation texts—like Hocquenghem’s “Towards a Homosexual View of the World,” as well as Mario Mieli’s Homosexuality and Liberation, or even more allegorically, Larry Mitchell’s The Faggots and their Friends Between Revolutions—acknowledged alongside feminist texts the patriarchal violence essential to the reproduction of capitalist relations, though often overlooking the racialized and colonial power structures that come to shape lived gender and sexuality. Hocquenghem repeatedly points to the way that the nuclear family works as a mini state: as he writes in Gay Liberation After ’68, “Most families are a daily hell, the father who yells at his kids because he can’t yell at his boss. And you want to reestablish parental authority, or rather make kids learn to obey, right? Is that it? Make women learn to stay in their place? Make men live by crushing their loved ones, to get revenge for being crushed elsewhere?” (Silvia Federici makes much the same argument against the nuclear family in “Wages Against Housework,” where she argues women must demand to be paid for the labor of keeping house and maintaining the illusion of family and love as a prelude to refusing the work.) More important, perhaps, for the young gay, is the experience of hiding it from a family, all while continually being identified anyway for not measuring up to the expectations of gender and sexuality. Hocquenghem dates his conscious realization of his sexuality to when his mother took him and said, “But at least you aren’t homosexual?” Of course, it wasn’t a revelation. But it still had to be said.

Hocquenghem writes and speaks from the position of a person whose sexual experience was formed in a relationship with his high school teacher, René Schérer, when he was fifteen. The two went on to collaborate for the rest of Hocquenghem’s life, notably on the book Co-Ire, which outlines what they call the system of childhood—perhaps less a defense of pederasty and more an examination of the creation of the child as a “minor,” an object of control, through ideas of innocence and the absence of sexuality. Integral to this was a desire to liberate young people from such constraints—granting the youth the power to determine their actions, and perhaps breaking beyond the drabness of straight penetrative sex, which for Hocquenghem was always about masculine domination (unlike what he saw as the parodic reversibility of gay sex). Hocquenghem writes as someone who did not feel harmed by his relationship with an older man, as someone whose revolutionary fervor awoke along with his sexuality. But this might be precisely what seems so dangerous.

The current reactionary movements—both right wing and “feminist”—against queer and trans bodies have come to consider the formation of queer kids as “grooming,” a term typically used to describe the way an adult manipulates a child into sexual abuse. In the current application, a parent’s mere acceptance of their child’s desire to be queer or to transition becomes indistinguishable from sexual abuse. This relies on the idea that a child cannot possibly know what they want, and should not, in any case, be supported in getting it. Yet there is a specious logic at play here: that an adult’s mere acknowledgment of transness, either as existing in the world or as one potentiality among many for their child, imposes that desire—as opposed to children and teenagers arriving at such a desire independently. Although an even bigger fear is that they arrive to this conclusion collectively—as a “trend,” a contagion.

More

Volutions

This related notion that transness spreads through social contagion was leveled at homosexuality in the past—and was proudly taken up by early gay liberation movements. The French government, for instance, declared homosexuality a social plague in 1960, and the FHAR used this as the name of their journal from 1972–1974. But you can’t simultaneously invoke the liberatory danger of queerness while playing the liberal game of looking for protection from the law, especially as it is intermittently applied on racial and class basis, and therefore still reasserts the essential “crime of homosexuality.” The contemporary far right views transness similarly: your kids will want to transition because they saw or had contact with a trans person. While grooming implies intentional preparation for abuse and manipulation, the contagion model happens beyond any individual will. It’s just out there—a ubiquitous threat.

This perspective brings into focus the actual aim of the anti-trans movement, which is about consolidating state control along the line of property rights. Gender is a form of discipline, the outcome of violence, both historical and contemporary, no matter the form it takes; we might even call normative parenting a form of grooming. A child conforming to their expected gender role would be the result of a job well done, the trans child an abject failure of gender discipline. Noah Zazanis, in “Social Reproduction and Social Cognition,” describes becoming cisgender as a more effective grooming: “Trans community influence must be considered in the full context of the many social influences dedicated to grooming children for cisgenderism, and depicting transition as the worst of all possible outcomes. . . . the structure of gender under capitalism is formed through violence in all cases.”

The major anti-trans talking point—that the grooming of children is only the visible side of a larger pedophilic attack on children—covers over the real fear: the fear of children having autonomy, which in a way would spell the end of childhood itself, the family’s control over social reproduction, and the state’s interest in sexual hegemony. In the accusation of grooming, as well as other forms of “woke” indoctrination, the necessity of controlling children appears self-evident, often under the banner of “parental rights.” Meanwhile, the abuse that more typically goes on within familial structures gets conveniently ignored: the child sexual abuse prevention group Darkness to Light reports that around 30 percent of children who are abused experience the abuse from a family member, and 60 percent of children who are abused experience abuse from someone the family trusts. But such statistics haven’t prompted a broader questioning of the nuclear family, or of parental rights to children—even when they are harming them.

Of course, the fake anxiety that white kids learning about the depravities of capitalism, colonialism, and slavery will wind up hating themselves maps onto the fear that those same kids might also be turned gay or trans by a nefarious queen at Drag Story Hour, if not through straight up recruitment. The real fear, of course, is that this generation will end the social order, which either gives parents paltry benefits, or makes them cling to the little stability they have. If we had a generation of white children ready to become race traitors and gender nihilists, along with prison and police abolitionists, and anti-capitalists, who knows what worlds could be built?

The parental rights discourse invokes the preciousness, the innocence of children, and treats them as property—which they effectively are. In this way, they are tabulae rasa, absorbing whatever is impressed upon them, which will eventually dictate their adult status. If they catch wind of the wrong thing—men loving men, boys wanting to be girls, satanic messages in music, the racism and abject suffering on which the current global system depends—they just might, as it were, veer off track. Here is the place where social reproduction is intimately felt, in the need for parents to control the sexual and gender development of their children, in the certainty that they know who their children really “are” and should become.

Liberation for gays, for women, will remain incomplete without ending the family form and the minoritization of children.

The confusing thing is that we can hear in the claim of parental rights the phrasing of a demand for liberation through recognition—just like the gay movement asserted its rights. But it is actually a claim of a right to property, identical to the desire for admission into the republic of sexes. Outside the progress narrative of an ever-expanding charmed circle, a pluralistic republic of sexes, this kind of social order always, inevitably, produces its abject, its reject. Liberation for gays, for women, will remain incomplete without ending the family form and the minoritization of children.

What we got instead was the horror that Hocquenghem described in La dérive homosexuelle: “The totalitarianism that follows for a person with a public sexual definition, about which everyone believes they have the right to have an opinion.” In the so-called marketplace of ideas, the battle is already lost when it can be defined as either “for” or “against.” Just look at the New York Times for their latest in a long line of surreptitious anti-trans opinion pieces, where “reasonable” critiques of transition are aired. Even when the editorial board was confronted by a group of contributing writers with a letter detailing the violent damage that their articles, which pose as objective while platforming anti-trans talking points, they simply responded with a defense of the notorious celebrity transphobe, J.K. Rowling, and a misleading conflation of the concerned writers with the media-monitoring group GLAAD. This lays the groundwork for anti-trans fascism. For all of these reasons, I can’t help but return to Valerie Solanas’s outrageous provocation, which gave the lie to, while taking the piss out of, both the women’s and gay movements: a world where all men either die or transition, and no one is invested in making children anymore. In other words, working not to repeat this awful world, but rather to end it.

If we follow Hocquenghem’s pessimistic reflection on gay liberation, we can see the traps ahead of us, as we try to insist on the rightness of transgender/transsexuality within our dominant institutions. Even if we are able to turn the tide against anti-trans legislation, the racial and gender code still operates along the lines of property, as evidenced most acutely in the status of the youth. The lost chance of gay liberation as Hocquenghem tells it rests in the commitments to ending the private engine of reproduction of capitalist and state relations: the family and the subordination of youth. This by no means entails a defense of pedophilia, but rather an understanding that children might know what they want—and might want things better than what we have or could even know.