By Sam Levin

The Guardian

February 18th, 2023

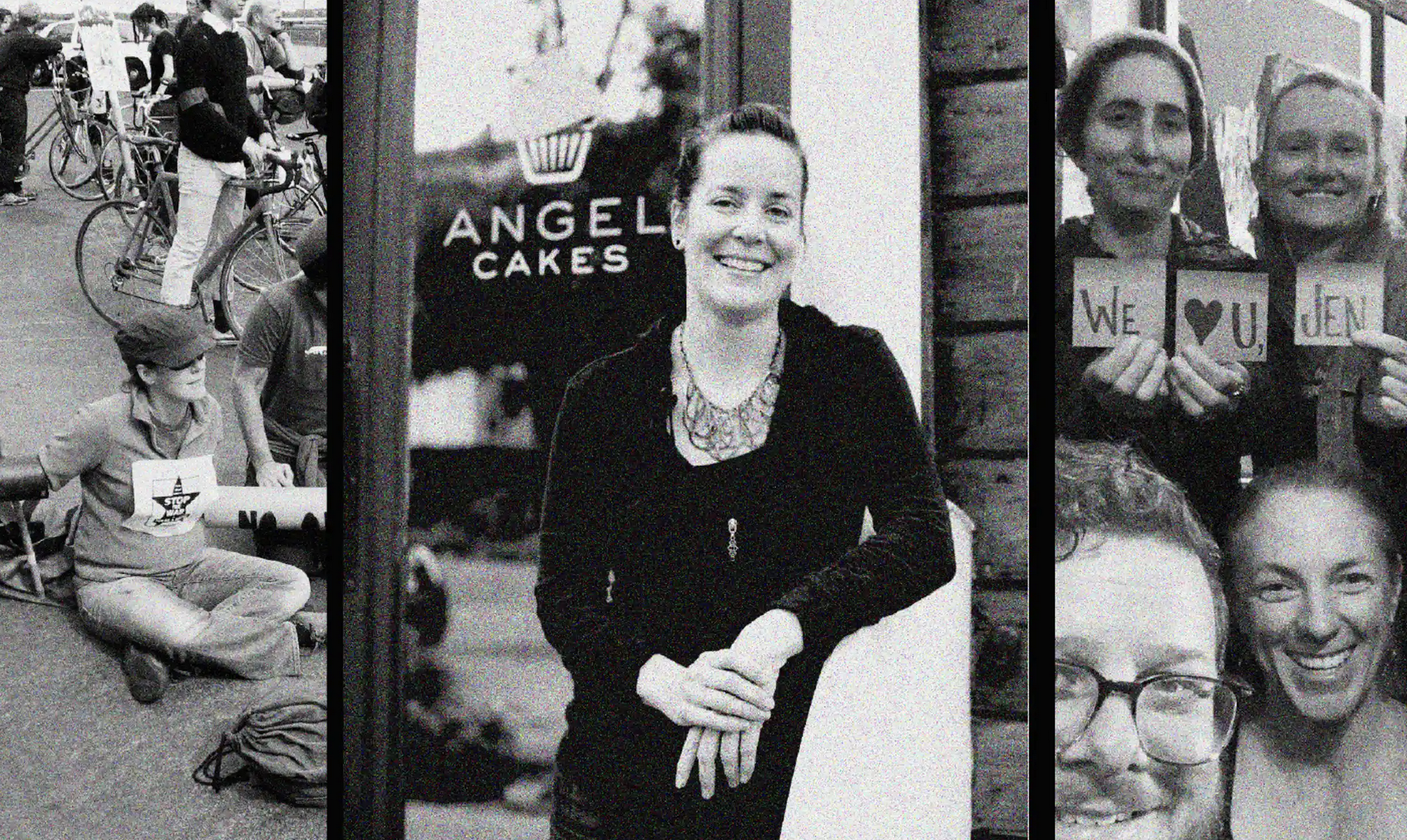

Jen Angel, a beloved Oakland baker and longtime activist, was in the parking lot of a bank on 6 February when she was robbed and then critically injured by the fleeing vehicle. The 48-year-old died three days later.

As word spread, Angel’s friends and loved ones did exactly what she would’ve done for them – they started organizing. They fundraised first for medical costs and then expenses related to her death, created spreadsheets to coordinate tasks, and formed a plan to ensure her bakery, Angel Cakes, would stay open and employees would be cared for. It was the kind of mutual aid and collective action she’d championed as a social justice advocate and anarchist. And as reporters began reaching out, her friends wrote a statement imploring them not to exploit her story:

“Jen’s values call for pursuing all available alternatives to traditional prosecution, such as restorative justice … Please do not use Jen’s life legacy of care and community to further inflame narratives of fear, hatred and vengeance. Jen would not want to advance putting public resources into policing, incarceration, or other state violence that perpetuates the cycles of violence that resulted in this tragedy.”

Pete Woiwode, a longtime friend, said Angel was steadfast in her opposition to prisons and support of community-based accountability: “I have an enormous amount of gratitude for Jen’s clarity and her mandate to us in our grief … And as Jen often says: ‘We don’t ask anybody to organize forus, we organize for ourselves.’ So we’re organizing.”

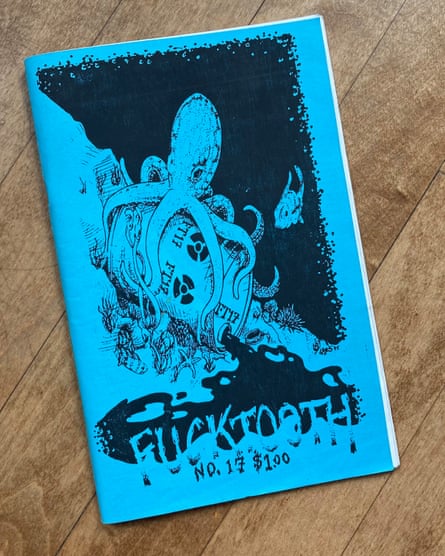

Jen Angel’s first zine, Fucktooth, which she started publishing as a teenager. Photograph: Courtesy of Loved Ones of Jen Angel

As the call for restorative justice has gone viral, Angel’s friends said her rejection of policing just scratches the surface of her politics and impact; interviews with a dozen loved ones and collaborators paint a picture of a fiercely-driven activist who had a huge reach across social movements, but never sought the kind of fame she’s now receiving.

Teen zines to major media institutions

Angel grew up in the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, and at age 16 in 1991, launched her first zine, called Fucktooth. She wrote about her life and interviewed punk inspirations and it quickly became popular in the underground DIY scene and punk subculture.

Matt Leonard, also a teen at the time, found the zine at a concert and became Angel’s pen pal, sending $1 to $2 in the mail in exchange for Fucktooth issues: “If you’re a young person feeling that the dominant culture doesn’t reflect your values, whether due to racism, sexism, homophobia, the aesthetics of pop culture or musical interests, some people just complain about it, but Jen was always someone who said: ‘No, I’m going to build the things I want and create what I want to see.’” The two later became close friends.

Angel went on to found Clamor magazine, billed as a “DIY guide to everyday revolution”. The journalist Victoria Law said Angel was the first person to pay her to write about resistance in women’s prisons in the early 2000s: “Not a lot of organizers and activists were even thinking about that at the time.” When one prison later demanded Clamor reveal Law’s whistleblower source, Angel refused and assured Law she’d have her back. Law later published multiple books on the subject.

Over the years, Angel was dedicated to anti-war activism, Occupy Oakland, workers’ rights, fighting fossil fuel companies, and police and prison abolition. She developed lasting projects that brought those movements to a wider audience, including Agency, an anarchist PR project; Aid & Abet, an event management group; and the Allied Media Conference, a network for organizing that has continued for more than 20 years.

She understood that “the story is power and has to be at the center of your work”, said Woiwode. Ramsey Kanaan, a publisher who worked on the Bay Area Anarchist Book Fair with Angel, described Angel as the “typical unsung hero – the person that actually got shit done”.

Angel was particularly skilled at welcoming new people into organizing and executing ambitious projects that helped shift culture, said activist Chris Crass: “She was concerned with creating massive opportunities for people to be on the right side of history – the side of anti-racism, feminism, queer and trans liberation and economic justice … And she was so fucking nonchalant about it. She didn’t have to tell you she was a badass, she just was.”

Her partner, Ocean Mottley, recalled her “lust for living” and said that on their first date at Oakland’s Lake Merritt, they hugged upon meeting, and that after a few steps, she asked for a second hug – a good sign for their future together. “She always had questions for people because she was so curious and wanted to know all about you,” he said in an email. “I got a sense very early from being with Jen that it meant being part of something much bigger.”

Angel, her loved ones said, also cultivated diverse polyamorous and sex-positive communities; loved clothing swaps; was fond of nature and rose gardens; and had a keen ability to bring people together through food.

Jen Angel hosted ‘gourmet dinner nights’ in Oakland. Photograph: Courtesy of Loved Ones of Jen Angel

The community bakery

Angel regularly hosted “gourmet dinner nights” in Oakland, recalled Nupur Modi-Parekh, a close friend: “The idea was we’re gonna put love, energy and time into making good food, and we want you to come enjoy it, with no obligation to contribute. That was her [philosophy] – we take care of each other and you don’t need to bring something to the table every time.”

At one gathering in 2008, she made cupcakes decorated like sunflowers that were “as delicious as they were beautiful”, recalled Woiwode, who said the group encouraged her to go professional, and that the next day, she emailed them a potential business plan.

Angel Cakes launched that year and then in 2016 opened its first storefront, in a historic Oakland building designed to look like a gingerbread house. She had high standards for her products, recalled her mother, Pat Engel, who said in an email that she would spend hours at the shop with her daughter: “I would garden in the front, whatever I could do. Not decorate cupcakes, though. I had to train to do that! I had to practice a lot and show her sample versions before I could get anywhere near the cupcakes.” When Angel and her twin sister were children, her mom took a class so that she could bake them cakes of their choosing. Angel’s bakery bio celebrated her mom’s lessons: “Jen learned practically everything she knows from her mom.”

Engel added she wanted her daughter remembered for her kindness, recounting their annual vacations together, most recently in Jamaica, where they hand-fed water to hummingbirds – “one of our last significant events we shared together”.

At the bakery, Angel put her politics into practice – paying employees fair wages; donating to social justice causes; welcoming people home from prison with free cupcakes; and establishing policies against working with police to resolve issues.

When a car crashed into her business and when someone threw rocks through her window, she didn’t want the people responsible to be criminalized, her friends recalled.

‘Jen understood the role of the police in maintaining a system that is racist and not equitable.’ Photograph: Courtesy of Loved Ones of Jen Angel

‘She wouldn’t want more injustice’

Angel was consistent in her principles and her loved ones said they felt a duty to honor those beliefs after her death.

“Jen understood the role of the police in maintaining a system that is racist and not equitable for all. She was adamantly against using the state or police force to solve problems,” Mottley said. “I know she would have wanted to find a way to heal our communities from this tragedy that didn’t perpetuate more injustice. She believed that incarcerating the people who harmed her would only continue suffering. She believed injustice can only be healed through love and community.”

Emily Harris, a longtime friend and policy director at the Ella Baker Center, which advocates against incarceration, noted Angel’s own writing on the subject in 2013: “Accountability processes attempt to put many of my values into practice – mutual aid, respect, direct action, a DIY ethic, an acknowledgement that ‘crime,’ safety, harm and support are complex.”

Some have misunderstood “restorative justice” or non-cooperation with police to mean “doing nothing”, but Angel’s friends say it’s the opposite: it’s about prioritizing survivors’ needs and healing (which isn’t a focus of the criminal process) and having them dictate how people who caused harm can be accountable for their actions.

“What is beautiful about this moment and Jen’s legacy is that we get to lift up the fact that the current system’s ability to respond to violence is inadequate for what most victims and their families want,” Harris said. “How do we change the conditions of Oakland to prevent this harm in the future? That might be about supporting these individuals [who robbed her] so they never do harm like this again – and not by putting them in prison.”

Police have made no arrests in her death.

Kanaan said he was reminded of Voltairine de Cleyre, a US anarchist who was shot in 1902 by her former student but survived – and then advocated he not be imprisoned “for an act which was the product of a diseased brain”.

“Not a lot of people knew her at the time, but she became famous after the fact, and I suspect we’re going to see that with Jen.”

Earlier this week, her family held an “honor walk” in the hospital to commemorate Angel’s wish that her organs be donated; her mother noted that this “final act” would benefit the lives of up to 70 people and encouraged others to become donors in her honor: “Even if you’re young now, you never know what will happen tomorrow.”

On her 48th birthday, days before her death, Angel was reflecting on life and death, posting an excerpt from a Mary Oliver poem:

“Tell me, what else should I have done? Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon? Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?”

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you move on, I was hoping you would consider taking the step of supporting the Guardian’s journalism.

From Elon Musk to Rupert Murdoch, a small number of billionaire owners have a powerful hold on so much of the information that reaches the public about what’s happening in the world. The Guardian is different. We have no billionaire owner or shareholders to consider. Our journalism is produced to serve the public interest – not profit motives.

And we avoid the trap that befalls much US media – the tendency, born of a desire to please all sides, to engage in false equivalence in the name of neutrality. While fairness guides everything we do, we know there is a right and a wrong position in the fight against racism and for reproductive justice. When we report on issues like the climate crisis, we’re not afraid to name who is responsible. And as a global news organization, we’re able to provide a fresh, outsider perspective on US politics – one so often missing from the insular American media bubble.

Around the world, readers can access the Guardian’s paywall-free journalism because of our unique reader-supported model. That’s because of people like you. Our readers keep us independent, beholden to no outside influence and accessible to everyone – whether they can afford to pay for news, or not.