by James Sallis

F&SF

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985, edited by Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre, PM Press, 2021, $29.95

Reverse Colonization: Science Fiction, Imperial Fantasy, and Alt-victimhood, by David M. Higgins, University of Iowa Press, 2021, $39.95

Occasional Views, Volume 1, by Samuel R. Delany, Wesleyan University Press, 2021, $24.95

________

History, to be useful and in any true sense accurate, must be anecdotal, a compendium assembled from multiple points of view and perspectives. Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is not, as the title might suggest, a deliberation on Ellison’s anthology and Moorcock’s magazine; its aim is much broader. It strives to document major trends and publications that, mid-century on, helped bring radical, substantive – and enduring – change to the field.

This, from the editors’ introduction:

Science fiction, with its basis in speculation, possibilities, and the future, became the ideal vessel for expression in an era in which the focus of many was on the questioning and refusal of established power and social relations, on the one hand, and the exhortation and exploration of radical scenarios, on the other.

Chiefly concerned with cultural expression and social recognition, the editors continue, these resistance and liberatory movements opened “a flood of new work that challenged and destabilized the conservative norms of narrative and expression, as well as outlook and belief.”

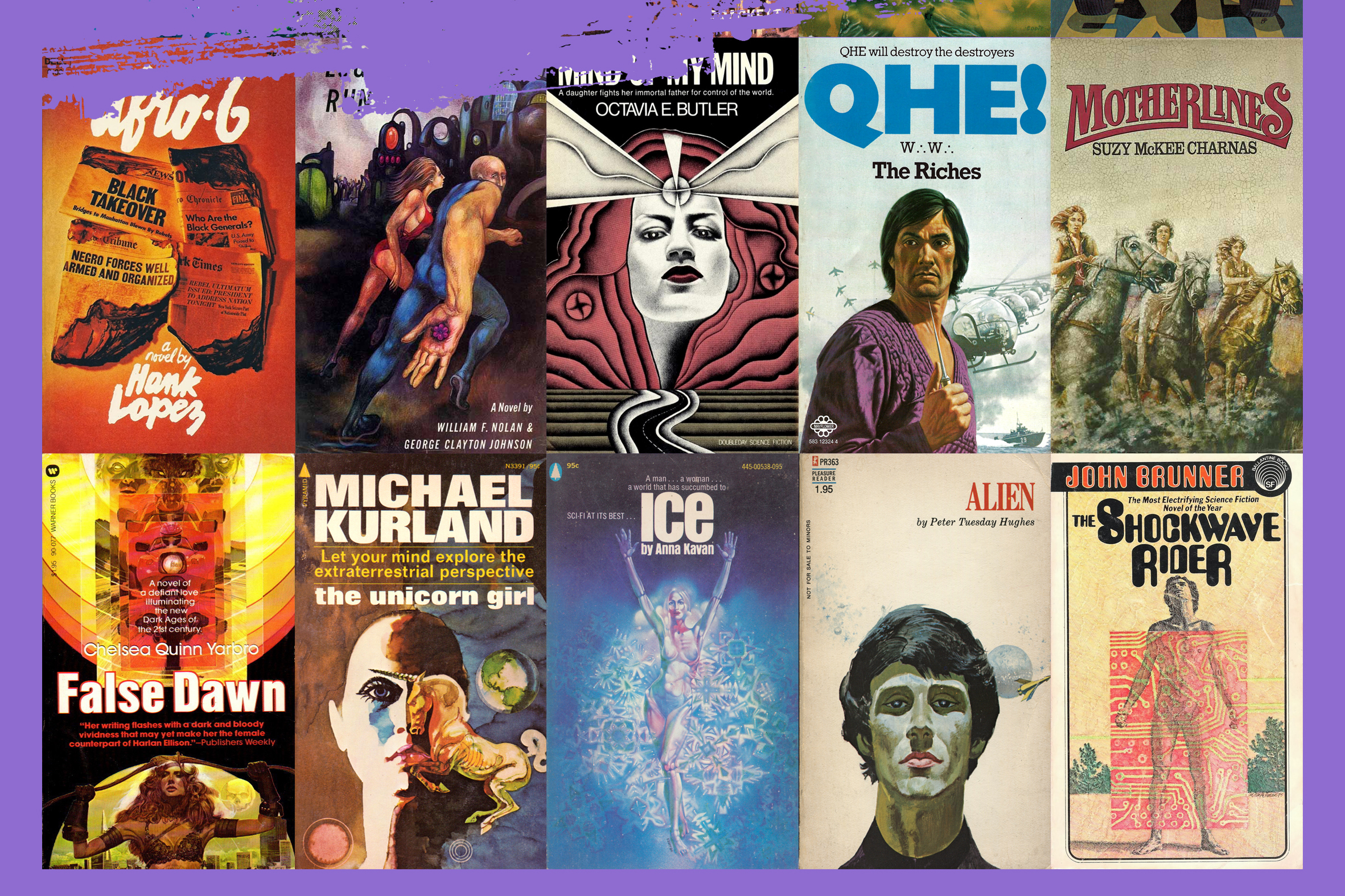

Thirty-five years of books, of catalogs and literary crawlspaces, countless diverse authors, editors, and publishers, not to mention 22 contributors to this 209-page, 8×10 book, make for quite a mixed lot, of course: pop culture history, bits of lit crit channeling Trilling’s “adversary intent,” bloodhounds with prey at bay, the occasional daft electrician looking for connections. All of it immensely readable and shot through with photos of writers and with absolutely wonderful book covers, hundreds of them.

Some pieces here, like that on Barry Malzberg, are brief, almost squiblike. Others, such as “The Stars My Destination: The Future According to Gay Adult Science Fiction Novels of the 1970s” lean towards, if not the comprehensive, then certainly the inclusive. A few further titles give some sense of the book’s reach:

Flawed Ancients, New Gods, and Interstellar Missionaries: Religion in Postwar SF

Flying Saucers and Black Power: Joseph Denis Jackson’s 1967 Insurrectionist Novel

The Black Commandos

A New Wave in the East: The Strugatsky Brothers and Radical Sci-fi in Soviet Russia

On Earth the Air Is Free: The Feminist Science Fiction of Judith Merril

There are outliers and oddballs here, Hank Lopez’s Afro-6 and Louise Lawrence’s Andra for instance, or the detailed look at Essex House’s own brand of sex-and-SF. Even the shorter pieces have weight to them, as with co-editor Iain McIntyre’s underscoring of a line from the Quatermass TV series and books directly to the UK’s then-current political situation: “imperial decline…ill effects of militarism, dodgy corporate dealings…a sense of impending catastrophe” – the very narrative of looming social chaos, McIntyre writes, used by the right wing to bring Margaret Thatcher to power.

Among the throng, several, for this reader, stand out.

Daniel Shank Cruz writes persuasively of the importance of Heavenly Breakfast, a book generally overlooked, both as “an examination of communal living and this model’s politically queer aspects” and as a helpmate in understanding Delany’s SF and later work. In much the same light, Kelly Roberts’ elaborates the darker underpinnings of a novel generally passed over as routine action-adventure, Roger Zelazny’s Damnation Alley, citing Hunter Thompson’s recognition of biker gangs as “not some romantic leftover, but the first wave of a future that nothing in our history has prepared us to cope with,” a group of fellow citizens who have cultivated powerful resentments on their way to becoming a destructive cult.

In “The Moons of Le Guin and Heinlein” Donna Glee Williams takes a close look at The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress and The Dispossessed as vividly distinct internal portraits of anarchist governments.

There have rarely been two books so closely related, so superficially similar, and so different in thrust […] For Heinlein, the principles might be described as “masculine,” individualist, libertarian, laissez-faire capitalist, and based on Christianity. For Le Guin, the governing principles might be described as feminist, communal, centrally coordinated, anarchist, and Taoist.

Kirsten Bussière’s “Feminist Future: Time Travel in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time” examines how this tale of a poor woman of color experiencing two distinct futures, one far better than her own, one far worse, broke ground in pivoting off the belief that such experiential knowledge could act as political motivator and establish new possibilities of personal, then social, agency. Bussière lays claim to the novel, published in 1976, as “a literary artifact of American cultural concerns regarding minority groups that were percolating in contemporary discourse,” and one whose importance persists. She quotes from an intro Piercy herself wrote for a 2016 edition of Woman on the Edge of Time, in which Piercy pointed to the ever-increasing incidence of poor and of people and families wiped out by bad health or lost jobs, to diminished chances for education, to the decline of unions and abandonment of other forms of worker protection.

“We are all,” Bussière writes, in ending – and indeed we remain – “on the edge of time.”

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds comes to us courtesy of PM Press, which earlier published Nette’s and McIntyre’s Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 and Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950-1980. Founded in 2007, PM has turned out a steady flow of studies of popular culture along with books on radical causes and progressive issues. Its Outspoken Authors imprint offers, among others, collections by Delany, Piercy, Joe Lansdale, Liz Hand, Nalo Hopkinson, and Paul Park; they’ve also brought out a new uniform edition of Mike Moorcock’s four masterful Pyatt novels.

#