By Charlie Allison

(This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity, consistency and flow. Any discrepancy

between the audio and the written form is entirely my own fault).

Transcript finished December 2nd, 2022.

Updated: December 12th 2022

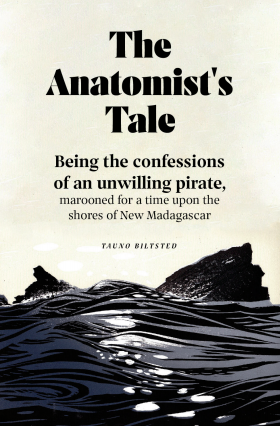

Tauno Biltsted – Former cab driver, Lower East Side squatter, mediator and facilitator, decent plumber and electrician, fiction and non-fiction writer. Tauno’s first novel, “The Anatomist’s Tale,” a speculative historical fiction about pirates and maroons who form a tropical commune, was published by Lanternfish Press in 2020. In addition to The Anatomist’s Tale, Tauno has published short stories with Rosebud Magazine, with Akashic Books Mondays are Murder webseries, and written for World War III Illustrated, and on black labor history and the IWW for Verso Books. Tauno recently published an article on consensus democracy, “Black Sheep of all Classes” with the Institute for Anarchist Studies.

Charlie Allison (CA): You’ve been involved in squatting and direct action for decades. What

are the big changes you’ve seen in your lifetime?

Tauno Biltsted (TB): Yeah. Being involved with squatting and direct action, maybe I should be more

specific. Squatting is this particular act of taking and/or rebuilding a building or space. I visited

different squats and squatting scenes in Europe and parts of the States and I’m very curious

about that sort of community building piece of that.

I’ve also been involved in direct action campaigns and adjacent stuff but I don’t nearly have the

same sort of direct experience with my friends or comrades who were involved with you know,

ELF [Earth Liberation Front] stuff or other sorts of actions like that.

The tradition of direct action in the United States goes back really far ( L.A. Kauffman’ s book,

DIRECT ACTION IN THE UNITED STATES is a great source for this). The book opens with a

shutdown in the Vietnam war— it opens with an attempt where masses of people were trying to

shut down Washington DC. That’s in her tracing of direct action, as a campaign, that’s where

she goes to look in the United States.

Is it ok if I tangent a little bit?

CA: Yes, of course!

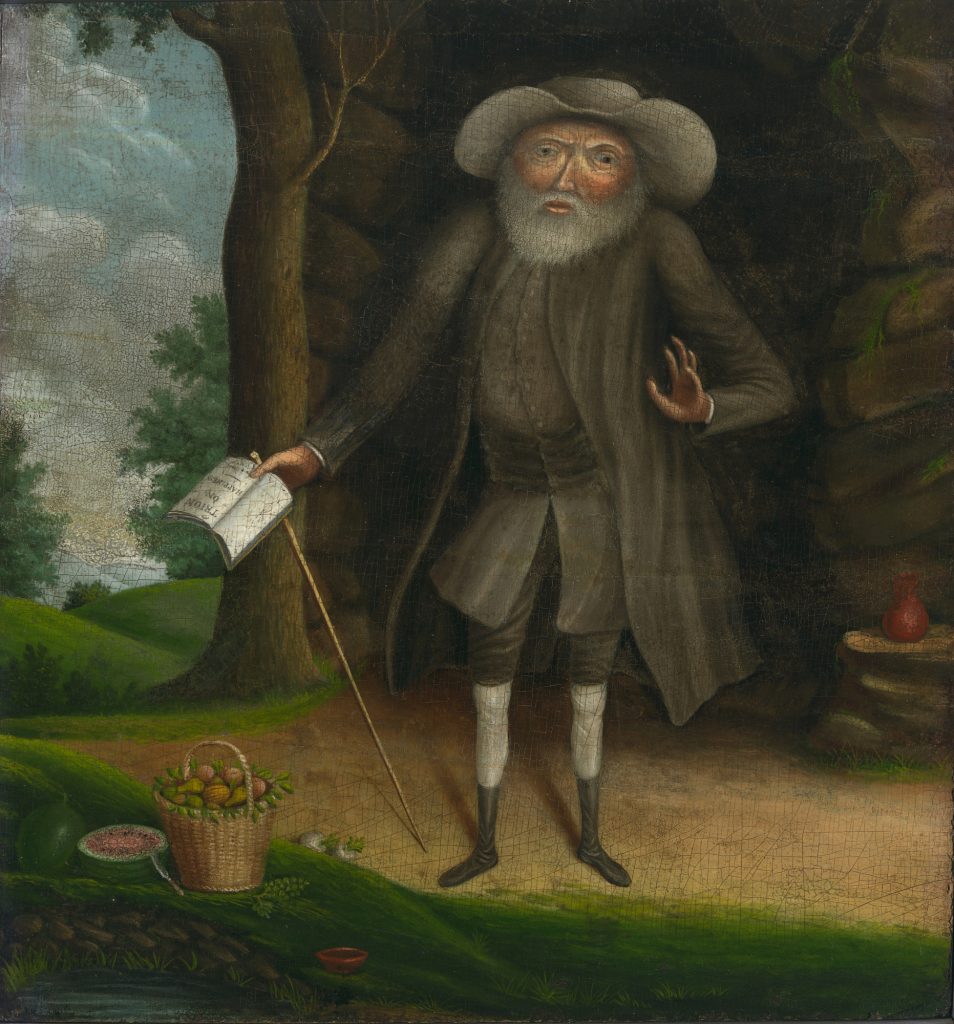

TB: Have you ever heard of Benjamin Lay?

CA: I feel like I should have, but I haven’t.

TB: Benjamin Lay was an abolitionist Quaker. He was also a dwarf, and a vegan, and lived in a cave

outside of Philadelphia. There is a book out about him by Marcus Rediker (author of stuff on pirates).

CA: Didn’t Rediker also write THE MANY HEADED HYDRA?

TB: Yeah. You know, I sort of crossed paths, intellectually with Marcus Rediker and his historical

writing, which is amazing. So anyway, Rediker also wrote a book about Benjamin Lay. Benjamin

Lay, at the time, was a radical abolitionist within the Quaker Church, and this was before, I think

the Quakers later took a position as a church around slavery, but maybe not even as a church.

But anyway, there was a lot of Quakers involved with slavery, and some who weren’t. Some of

those who weren’t were actively and vocally opposed to it.

Benjamin [Lay] would do these ‘actions’ outside of Church. He’d get up and cover himself in

blood, to represent the blood of enslaved people and shame the slaveholders in the

congregation, and various other kinda things like that.

So direct action has a long and storied and multiplicitous and wonderful kinda history. I can

speak to my own piece of the experience of it, in my own realm.

So in terms of differences specifically between squatting and direct action, one of the big

differences is just space, material circumstances. The ability—which varies in terms of cities,

especially ones in this countries that are ‘emptying out’—one of the primary needs for that

relationship to space for a group or person, to invade space and make it theirs—you need

something that has been derelict.

That’s something that’s really changed. The opportunity for people to experiment with empty

space in metropolitan spaces, has really, fundamentally changed.

CA: Squatting and direct action has a particularly long history. You mentioned to me earlier

that you have a background in both Danish and American cultures. What are some of the

differences you see in the directly democratic organizations like squatting between those

two cultures? More importantly, are their commonalities we can learn from?

TB: My experiences are mostly from long ago. It was the 80s and 90s. Folks who were squatting

were highly politically active in Copenhagen. The context was that I was there through family

and then I went back when I was in my late teen/early 20s and knew a crew of people who were

squatters or ex-squatters—involved in the left-radical scene, in a commune or a collective

space.

In terms of the differences between the two countries, maybe it’s more in terms of what they

face [in terms of opposition]. It’s almost cliche, but Denmark—and I’m not sure that this is all

that explains it—is a diversifying country. There has been a wave of Turkish migrants that

started coming in in the sixties and then a lot of refugees, especially in the cities. Though that

was less so 20-30 years ago.

Highly active people, all kinds of political actions, planning a lot of different creative things—all

sorts of different flavors of radical scenes. There were certainly disagreements and differences

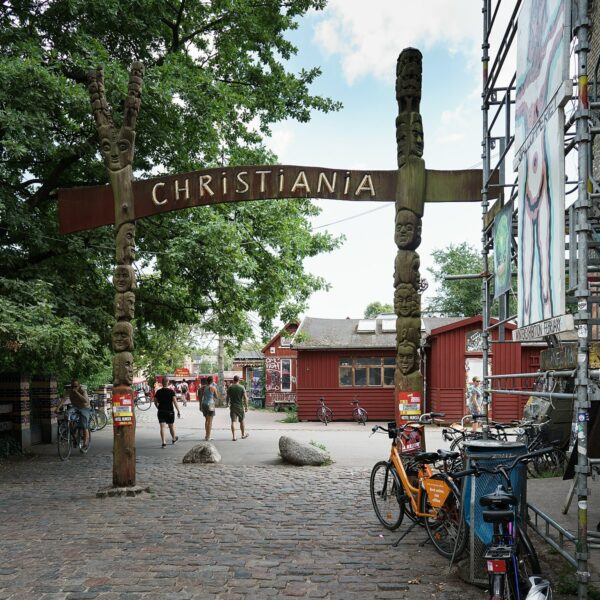

of opinion, and in Christiania —part of the reason we’re talking—Christiana was riven by all

kinds of internal conflicts over the years.

So it’s not like people were shy about voicing their discontent or falling out with each other or

even becoming lifelong enemies.

However, somehow, the gravity of the disputes or splits within the scene, in my experience,

wasn’t enough to kinda spin everything out.

People—both with what we can see with Christiania—this community that has been there for

fifty years under a great deal of stress—has managed to in whatever ramshackle way, to

maintain a democratic and horizontal space and ethic.

That, and also, my insight with the youth squatter scene in the 90s—who were serious

people—I’ve never seen street-fighting like I’ve seen amongst those kids. They fought the cops.

They did some really brave and amazing actions. They did anti-fascist work, going to meetings,

shutting down [fascist] events—in a word, they were militant.

This driving force was not overly disrupted or diluted by the splits.

CA: How does this compare to the effect of splits on American activist scenes?

TB: There is a way, which is one of the differences with the American scene, with their direct

action/squatting scene wouldn’t be the opposite of the Danish one. It’s not as if the splits are

more of a problem in the US or less of a problem, so its not on that kind of continuum. But they

do sometimes have a huge disruptive impacts on the organizations.

This tendency towards splitting and coming together, and maybe the cycle of it, in the US at

least, is really fast.

A lot of [disputes] cycles fairly quickly. I don’t know, maybe our ability to, as a scene, as a group,

isn’t always so great in terms of dealing with the splits in the moment.

Although the sheer enormity of conditions in America keep pushing everybody together. How

hard things are here socially, the demand for movements, for people to do stuff is so high, so we

keep coming back together.

I’m not referring to splits along any particular lines but like, conflicts, territorial struggles, stuff

like that as not a main feature but definitely a significant feature of a lot of movement stuff, the

squatting/direct action sphere that I’ve experienced.

CA: Gotcha. So if I’m understanding the broad thrust of this, it’s not necessarily that

American squatting culture and actions—splits—are more severe, its just that they can

and tend to happen more rapidly and are thusly a bit more destructive, than say, in

Christiania?

TB: Yeah, I think the cycle of them is a thing. I think I’m also saying that the [American] splits are

more destabilizing for the groups. Splits can be generative or whatever, but it just seems like the

cycle can be destabilizing.

When you look at a history of American organizations, there are a lot of splits! Things fall apart.

Or, they institutionalize—which is a certain way of falling apart.

CA: Falling apart into a hierarchal structure: the story of unions in America.

TB: Yeah.

CA: So a really fascinating thing—and I’ve never heard this term before before reading your

article on Christiania—is the concept of ‘feedback loops’ in Christiania . Can you elaborate a bit

on that, for people who may be a little less familiar with the concept?

TB: Yes, definitely. Feedback loops are pretty interesting. So I went in [to Christiania], and my

method (I speak Danish, learned it as a kid) and interview as many people as possible.

CA: How do they feel about consensus and the system there? How does it work for them, how do

they feel within the system etc.

TB: I learned in that process, about the way that the space works. I didn’t do a lot of in-depth

research[beforehand]—I was aware, structurally and in general of course, but mostly I listened

to people’s stories.

To connect that to the feedback loops—to them, the structures and stuff of how it worked there

became clearer and clearer. It [Christiania] is divided. There is the community/common meeting,

which has the highest level of authority. Everyone lives in their particular, område or areas.

People would talk about relationships or initiatives within the Områder [area] and how they

wanted something that was in another neighborhood.

An example I could give would be the heating thing.

Obviously heating is a huge deal, especially in a former military barracks. There are some big

industrial structures, smaller sheds, officers quarters, stuff like that.

And so, in the different areas, they govern themselves essentially, up to a certain point. They

have an area of governance. They approve people coming in, they approve development

projects, both individual units as well as common, within their area.

Obviously heating is a big thing, there is a huge cost advantage, energy expenses stuff like

that. Huge cost advantage to having collective heating.

To get collective heating[in Christiania], you have to convince your neighbors you should all

invest in upgrading, essentially. Make the investment because there is gonna be some out of

pocket expenses, and upgrade your heating for the whole area to reduce expenses over time.

And you think, great, isn’t everyone doing this?

And different areas would for different reasons, decide [to collectivize heat] or not.

I spoke to several people who were frustrated because they tried to talk to their neighbors, their

own heaters were failing or were unsatisfying in some kind of way, they went and tried to

convince all their neighbors to upgrade but couldn’t. Their neighbors in their other places,

across the way, maybe already had heating, and there was some difference between locations.

Not necessarily about money, sometimes about local culture.

Its a very visceral way of experiencing the differences between areas. The relationship,

essentially what happened in Christiania, when they first squatted it, they were very idealistic.

They said ‘lets resolve everything all the time through talking through each other’. But then the

interests of different people, who were squatting in different areas, in different conditions, were

different enough that—for those folk over there, who needed windows because they were on a

fifth floor in an industrial building, were different from those folks across the way who really

needed to build a latrine because they were basically camping outside.

The two groups had different conversations to have. They realized that they needed to have

those conversations separately. The folks who need to build the latrines have their

conversations about that, the window folk talk about putting in their windows.

It was this organic way that different levels of authority developed, related directly to what was

of interest to those groups of people.

Are you following me, does that make sense?

CA: Yeah. It seems to play on—or avoid—the trap that James C. Scott talks about in SEEING

LIKE A STATE (with the famous subtitle: ‘Why Various Schemes to Improve the Human

Condition Have Failed’). Scott says that once you centralize control, start using cadastral

maps and start dictating topdown solutions regardless of local conditions, that’s when

you’re doomed. That’s how you create policy that doesn’t reflect reality. So if I’m

understanding both your article and your excellent explanation of it, this was solved pre-

emptively through very local control—not always satisfactorily—but it was always local

control spreading outwards?

TB: Yes. And also local control organized around interests. I don’t want to say ‘natural interests’ but

the things that have people connected with each other in some way. What struck me, I guess

my point is, ‘I went into this, I want to talk about consensus, broadly, I’ve got thoughts about

organizational structures’.

I did some reading in preparation to going to Christiania—afterwards I had the opportunity to do

some more research around participatory democracy and structures.

I realized that this kind of system—of nested authority—is something that different places (and

these feedback loops) have figured out. The local has authority over the local. The general has

authority has authority over the general—paying the taxes, making sure the water bill comes in,

new construction in public areas etc. The local and the general have shared budgets. There is

overlap in the responsibility in what they share—they have shared interests.

For making those kinds of decisions—a choice made locally depending on the decisions—is

reviewed by the larger governing body and sent back to the local folks for implementation or

modified.

Sometimes the idea is rejected if it requires money from the general fund, in order to achieve

whatever the goal they’ve identified.

And so that’s where the feedback loop comes in: the nested authority. Constant feedback. Some

of it is approval, some of it is also debate. It’s not just ‘yes/no’, a lot more of ‘what about this

idea, what about this approach?’. It’s additive in some ways.

So later I was thinking about it, had done some more research. I was struck by the similarities in

the feedback loops, the attention paid to size of political units. The units of decision making,

kinda thing.

Learned a bit more details about the Zapatistas and how they have been experimenting with

governance after the reforms of like 2006/2007.

When they kinda set up different roles for Zapatista civil life or whatever. In those reforms and

the practices that developed since then, they’ve developed deliberative processes. Proposals

can be generated at the local levels, the regions, the caracoles, they could go to the governing

council. Then they can be modified or changed or rejected and sent back. There is a process of

conversation or deliberation that goes down and up, then up then down. It doesn’t necessarily

go in one direction. Because proposals can be developed at the top level and sent down to the

locals, to be accepted or rejected or modified.

There is some similarities in Kerala, India. I mentioned that in my piece [ on Christiania ]. In

Kerala, in the 90s, there was a constitutional amendment, empowering experiments in

participatory democracy.

Mind you, in India, this was amendment 72 or 73, they have a lot of amendments to their

constitution—it was written in the 40s. Anyway, Kerala, which has had a communist state

government for 30-40 years, has been very organized, a lot of organizations promoting

democratic and popular participation . Kerala really met the opportunity of this new space for

participatory democracy—they set up local councils around budget development, other

decisions and really have an impact on how development works, different kinds of policies in the

state of Kerala.

They also have a similar system of nested authority and feedback loops . It’s very simple. It’s just

like deciding ‘who decides what where’ and you know, having some kinda structure that tracks

that flow of authority back and forth. Again, a tracking of stronger or weaker shared authority by

all the different groups—including groups of representatives up and down this social scale or

space that is being governed.

CA: So instead of our very traditional linear concept of power, I’m starting to see why the

reason the term ‘feedback loops’ is being used. Because the local and broader-scale are constantly talking and negotiating and going around. Rather than by fiat ‘this will be,

whether its a good idea or not, no appeal!’ notion of power.

TB: Yes, it’s a kind of feedback loop. And it’s deliberative. There is room for deliberation around the

loop, it’s not just ‘yes/no’ answers. It’s not like ‘we’ve made our proposal: accept or deny!”

There is room for conversation, and a group thinking, collective thinking along the way.

CA: It seems like a flexible system. I think you hit the nail on the head on the least productive

way to frame a question is as ‘yes/no’—no wonder surveys love it. So, anyway, how did

that the community in India work out? Is it still around?

Yeah! Kerala is still around! They still have a government—basically the communist party of

Kerala—which, ok, whatever ideology-wise—is pretty left wing and not super-authoritarian and

is governing on the behalf of the people and working classes of Kerala. These experiments in

participatory democracy are continuing, actually—a whole lot of literature has sprung up to

study it. It’s continuing in terms of the Zapatistas as well, and the work they are doing there.

i know that the community with their position-related to drug trafficking, where they are on the

border, is really difficult. I’m sure that the Zapatistas territories are facing a lot of social

pressures. At the same time there is no indication of upheaval— they are continuing , they are

dealing with things, basically. They have not changed course in terms of their tactics for dealing

with things which is through conversation and shared political power.

CA: They’re definitely fascinating—they’ve not only managed to survive, but also to thrive, to

an extent. So, anyway, in your article, you write about a person becoming integrated into

Christiania after a period of time while being houseless. You talk about him gaining a

sense of purpose, work, and I was wondering if you could say more about Christiania’s

permeability to outsiders? High? Low? Medium?

TB: Nobody would say that Christiania is easy to get into, in that way. If someone was to just say

‘I’m choosing to go live there’, well, housing is difficult to get ahold of. And then, of course, all

over Copenhagen, it’s not easy to get housing either. The city has been built up quite a bit,

people don’t want to move.

Christiania does draw people in. It has a kind of social openness. There is room for people to

visit and have a sense of ownership and place, even if they don’t live there. So there are a lot of people who like it there, who hang out, who aren’t residents—they like the open space, or the cultures, or the subcultures inside those.

So this fellow I mentioned in my article, he was probably an alcoholic or in some kind of way

struggling. He ended up in Christiania, there were places he could sleep, people he could hang

out with, stuff like that. He started, slowly over time—and as I describe in the article—taking

care of something, finding a corner to take care of (the corner, in this case, happened to be a

bathroom). He didn’t mind it, and people around him appreciated it very much. Like ‘huh, this is

a suitable place for me to expend my energy and give something to this community that I’m

interested in.’ There was a place for him to plug in, that was appreciated.

Over time, there was also room for him to have a place to live. The community eventually

provided him housing—I don’t think it was like ‘he showed up, cleaned the bathrooms, got

housing immediately’.

It took a while.

Another key thing is that the community has the internal resources to pay him. The community

hires him to do this job, being that it’s a public space. They develop further public spaces to be

maintained, more public bathrooms to be maintained near one of the central plazas etc. And so

he became the person who was responsible for that.

What are some of the different elements of this situation? The opportunity for someone to come

and associate with the space without having to be like fully invested, more fully included either.

Both things being true. He didn’t have to become a member to be around the space and part of

the culture there, or the ethic or whatever. He didn’t have to be fully engaged or anything.

Also the opportunity for someone to do something, to be in the space, to make a contribution. Is

there some way they can make a contribution on their terms, essentially?

The other piece was having housing. He’d been there for a little while. I think there was a flux in

housing, people coming and going. Community resources, in a word, is what makes this whole

thing possible, alongside collective resources. Christiania could afford to pay him, is what I

mean. Though I should add that Christiania can’t pay everybody to take care of the place—they

don’t have the economy of scale for that—but what they do have is the collective will to upkeep

the place anyway.

CA: They’ve come a long way from the beginning to now. In your own experience in the Lower East Side in the nineties, we talked about this in our preliminary talk, you mentioned some of the trouble getting people who are not politically involved, in a struggle to own a building through squatting, involved. I guess it’s a similar question of integration. How has that gone about in the incorporation of your building?

TB: How did the group form and deal with not everybody having the same politics towards the

beginning? Something that was shared, when people were living here towards the beginning,

was work.

A tremendous amount of work was required. For years it was just getting garbage out of the

building, stabilizing beams, rough and dirty kind of work.

People were definitely working together, in some kinda way, even if they weren’t having political

conversations, they were having conversations about the work that they were doing.

It wasn’t that discussions were about politics outside the work—they could be!—but the main

thing connecting most people was this project. ‘In order for me to build the home I want to build,

I need you to build the home you want to build.’ They needed each other, essentially. Even if

they didn’t have shared politics, we still had a lot in common.

Eventually the building got built! Not that we built the building from the ground up, I mean

renovated or whatever. So then we have this consensus -1 decision making structure. There is

a generalized community ethic, and a generalized ethic of sharing and we have certain

practices and cultures around this kinda stuff. We have infrastructure—we built a roof garden

that everyone can partake in, grow vegetables there, take vegetables from there even if they

didn’t grow them themselves.

So we setup these structures—ways for people to coordinate with each other. This building

requires input there is something that has to be managed.

If something breaks, it needs to get fixed.

Somehow we’ve also gotten a practice of addressing those things together. A lot of these kind of

buildings when they go legal—not necessary all ex-squats—these kinda co-ops. We’re

technically a limited equity co-op. Its not unusual for those kinda places to have the board do

everything—you know—five guys who make every decision.

But in our building we have a culture of having conversations together, of solving problems

together. We still don’t have explicitly shared values sometimes and that can influence some of

how the conversations play out, or what people are trying to get out of the conversation.

We don’t have anything written down. No vision or mission.

We do have a structure that works, though.

Sometimes we can feel the absence of explicit shared goals—political shared projects, or even

our goals for our relationships with each other.

CA: So in this case its a triumph of solidarity and informal understandings?

TB: Yeah, it definitely is. One thing I was thinking about in terms of one of your questions was, ‘What

might I have done differently’?

One of the things I might have wished to do differently, from my experience in this place that has

been successful but also informal, how it’s held together with this group of eclectic people pretty

democratically—is we never developed systems of conflict resolution.

Really, it’s always like this: when something comes up, its already too late.

It’s hard to devise a system to diffuse or solve conflict in the middle of a conflict.

I wish that was something there had been some forethought in, not just where I live, but in other

projects. Some sort of preemptive thinking like, ‘Hey, how do we want to deal with conflict’?

CA: Yeah, means and ends and all that. That’s all the more remarkable that it’s remained informal, quite impressive. So to bring this full circle back to America—wait, so the building was entirely abandoned when you started, you started from 0?

TB: Yeah, the building was entirely abandoned.

CA: Damn. Philly is the 5th largest city in the country and we’re definitely up their in terms of

abandoned or ‘blighted buildings’. I’ve seen the insides of some of them and that does

not look like light work.

TB: Yeah. ‘My’ building had been previously squatted. It was a native American squat—a group of

native Americans who squatted this building up until some time in the 80s. They got evicted for

some reason or another, then the city paid a local organization to ‘seal the building’. Sealing the

building meant making it uninhabitable.

So what they did was knock out all the stairs, cut holes in the roof and blocked the sewer. To

make it uninhabitable and eventually collapse. It was deliberately done so that the building

would move towards collapsing.

THAT is the building that people moved into—I came in a couple years after it was squatted, but

it was still in construction.

CA: If I’m understanding this correctly, its less that it was abandoned. It was more ‘squatted,

people driven out, building actively sabotaged’.

TB: That’s was the condition, yeah.

CA: Fuck me. That’s a whole different story than ‘the building was beaten up’. I had no idea

that sort of practice was official policy. So, your building won incorporation after a time,

and you were involved in that.Tell me all about it, its something I know nothing about.

TB: Sure! There was a whole scene in this particular neighborhood. Each building was different,

some were punkier than others, others were more community based, a hippie building, what

have you. The point is that the buildings and their inhabitants had different qualities. We would

defend each other.

But what we did was community self defense. When the cops or the city came after a building,

we would organize and show up. Help with legal stuff, organize, make noise. Under Giuliani in

the 90s, the focus of the city of New York was breaking up the squats.

Typical fascist political target, pick a target and try to get rid of them. He targeted community

gardens at first, then moved to the squats. It was part of that whole neoliberal privatizing

agenda, mixed with some personal vendettas.

Anyway, people in the squatting scene didn’t go easy. They made a fuss. Legal struggles. Cost

the city a whole bunch of money. Anytime the city showed up at a squat we fought back.

There was a group of buildings on 13th street in the neighborhood, year long legal battle. Then

when the city went to evict them, the barricades went up. But in the end they were evicted. The

city came in with a tank, or whatever. This was in the late 90s—97, 98.

After that the city responded to overtures from a group of buildings that had been represented

by a middleman, dedicated to helping homesteaders, had been since the 70s. We were like

‘Hey, would you consider approaching the city about legalization? We’re willing to negotiate.’

Eventually the city got back to us—towards the end of Giuliani’s term and talks began. Took a

couple years.

Turns out we fit into this little legal shape in New York’s legal code: the limited equity co-

operative. We don’t pay property taxes, in return we have caps on resale and income

requirements to move in. So we’re self-managing, we have a monitor, to show we’re following

the basic requirements to keep the building affordable.

Other than that, we manage ourselves. We have a couple of storefronts that we rent to vendors

at below market, but not hugely below market kinda thing. A barbershop, those type of guys.

That’s the structure. And that’s the process.

A lot of other places are experimenting with community land trusts—we might have been able to

do that but the eagerness for organizing has faded nowadays.

CA: Fascinating. It’s not often you find something in American law that’s favorable to

common ownership or self-management, to let one slip through the cracks.

TB: It wasn’t because we squatted that we eventually came into legal ownership of the buildings. In

fact, whatever sort of statues in the legal code—the possibility of squatting a building for ten

years ‘openly and notoriously’ to get ownership that way— in the end of the day, those statues

have been overturned. Or rather, new precedents that are bad for squatting rights have been

set.

We won our building through political struggle. Not broadly social power, but specifically,

resisting eviction.

First we made ourselves legitimate by being here, fixing the buildings up, showed ourselves to

be moderately productive for a couple of years because everything was so chaotic and crazy.

CA: Gotcha. That context is important. Still wild to me. To bring us full circle to American

history, lets talk about your historical novel The Anatomist’s Tale . You and I have talked

about it before, around when it first came out. For the people in the cheap seats who

missed that maybe, what were some of your favorite parts of researching pirate

communes in the Caribbean, maroons? Is there a source you’d be particularly excited to

‘see’ again, as if for the first time? This is a broad, rambling question, so i’m hoping for

one of your broad, wonderfully rambling answers.

TB: I think the thing—one of the things that strikes me as kinda surprising in doing historical

research and looking into different cultures and times—is the surprising way that people are

people. People are people all the way through, across all kinds of cultures that never met, in

their idiosyncratic ways. One of those key commonalities is a person’s desire to lead dignified

lives, and resisting things that get in the way of that. The ways people organize themselves.

There was great variability that pirates organized themselves: sometimes the pirate structure

was very top-down and the pirate captain’s word was law.

More frequently than not, pirates had a certain code of disrespecting authority, and shared

decision making. Shared authority and rights in relation to each other and to whatever riches

they got. In these ways of democratic organization—on ship or in Maroon villages. This goes

back further than most people imagine—from the time of Caesar in the Mediterranean to the

Caribbean to ten years ago off the coast of Somalia. There are similarities in ways that pirates

have organized themselves across time.

Including escaped slaves from Florida, Honduras, Brazil.

I was struck by one of the research sources in particular: Andrew Solomon’s book The Noonday

Demon , a history of mental illness, depression.

In my work, one of my minor characters has a bout of mental illness. I was curious and reading

about that and the particular way that people imagine what was happening to them as they were

suffering the symptoms of what would be today, classifiable mental illness. The differences

between then and now, to grasp at these symptoms and try and understand them.

There are so many ways of trying to understand human experiences. I was really into escaped

slave texts, travel narratives. Abolitionist presses would publish these accounts—one of them

was made into a movie ( 12 YEARS A SLAVE) . But that has an effect—across time, across

cultures, you can put yourself into someone else’s head who has a lot in common with you but a

lot different as well.

CA: I could see how that would be heartening and depressing at the time. Last question!

What’s next for you, what projects are you working on?

TB: I’m working on a novel, that is kinda speculative fiction. Both a little bit in the future and sort of in

deep history. I have been trying to write this story, basically, but I have given myself the

particular problem of a lot of things happening at different times, and following my curiosity.

Beyond that, continuing work here and there. Some paid writing projects that I’m also doing and

other areas of my life that are spinning their wheels at the same time.

CA: That sounds wonderfully omnivorous and I can’t wait to read it when it comes out!

TB: Fingers crossed!