The historian and activist dedicated his life to showing how, and helping, working people not only imagine but build a better world.

hen Staughton Lynd, Tom Hayden, and Herbert Aptheker traveled to Hanoi to declare peace with the Vietnamese people in 1965, they stopped off in Paris to meet several North Vietnamese officials. After a long discussion, a small, elderly Vietnamese man pulled Staughton aside and said to him, “Professor Lynd, you need to understand that we are going to win this war whether you help us or not. For every soldier killed by the United States military, two will join the National Liberation Front.” Staughton enjoyed telling this story about someone who had knocked him off his savior’s horse and put him in his place with only two sentences. Staughton would add, recalling the story: “That’s the kind of dialectical thinker I would like to become.”

The last line was pure Staughton. He was always becoming, always changing, always seeking as the times and the movements from below changed. Working with his partner Alice (Niles) Lynd, he relentlessly sought out new sources of combat and inspiration.

Staughton’s approach to thinking, writing, and activism was straightforward: Go to the front line of the struggle, listen, learn, and make your skills available to the people who are waging the fight. He wanted to think with people, not for them. Over time he developed a theory of “accompaniment,” based partly on the ideas of Oscar Romero, the peoples’ priest in El Salvador who was assassinated in 1980.

The trip to Vietnam cost Staughton his position in the history department at Yale, and eventually it cost him his ability to work as a professional historian, as he was effectively blackballed from the university system. Staughton was subsequently offered five positions, all rescinded by deans who were pressured not to hire him. Staughton’s blacklisting wounded him deeply, for he loved the practice of history. He was already by this time an essential figure in what he and others liked to call “history from the bottom up,” the insurgent history of the New Left that studied working people not as mere subjects but as makers of history.

But Staughton thought about his career misfortune dialectically: His firing, he told me on more than one occasion, was “one of the best things that ever happened to me.” It may have cut him off from the work he loved, but it freed him from the academic life he was born into and in which he had already ascended to a high level. He was now free to think, write, and organize in new ways. He retooled as an attorney with a simple goal: He wanted to be in a roomful of workers and activists and when someone asked, “Who is that guy?,” the answer would be, “He’s our lawyer.”

Anti-vanguardist to the core, Staughton believed that working people could imagine and build a better world. He continued to write what he called “guerrilla history,” that is, history from the cutting edge of the struggle, whether a picket line or a prison cell, for the rest of his life.

Staughton sought out the unity among various struggles from below. He campaigned against the Cold War and its nuclear obsession, against white supremacy, against American imperialism, against the closure of steel plants in Youngstown and Pittsburgh, against capital punishment and the prison-industrial complex, against capitalism and its oppression of workers. He believed with all his heart that the major political task of our time was to build a movement culture that would, as he put it, “connect the dots.” It would be hard to find a radical thinker who made significant contributions to so many different movements from below.

Staughton loved the religious radicals chronicled by Christopher Hill in his 1972 classic The World Turned Upside Down: Radical Ideas during the English Revolution—the heretical Levelers, Diggers, Ranters, Seekers, Quakers, and Muggletonians who proposed their own revolutionary solutions to the crisis of the 17th century. I once took Hill to a meeting of the Youngstown Workers’ Solidarity Club. On arrival, Staughton embraced Christopher and told him that the 15 people in the room were the modern-day Levelers. Staughton and Christopher shared a deep, knowing laugh about how history is made.

If E.P. Thompson was, as he called himself, a “Muggletonian Marxist,” referring to the radical Protestant group founded by Lodowicke Muggleton in 1651, Staughton was, much more literally, a Quaker Marxist. Or was he a Marxist Quaker? It was hard to know which of those two bodies of thought was more important to him.

From Marx—as well as from his disciples C.L.R. James and Marty Glaberman—he took the concept “working-class self-activity” and built a body of work, agitation, and organizing around it. The impulse was to study what the working class had done to achieve its own liberation, with special emphasis on what new forms of self-organization workers had developed. Shopfloor struggles loomed large in this formulation. Staughton became a fierce critic of the top-down, hierarchical model of organizing carried out by the CIO.

At the same time, Quakerism and its values of spiritual equality, humility, and simplicity were guiding lights throughout his life. Anyone who visited Staughton and Alice in their small home in Niles, Ohio, could see immediately that these people did not covet worldly goods. Property did not mediate their human relationships. They lived according to the old Quaker phrase, “Let your life speak.” An exemplary life, Quakers believed, would be an inspiration to others, as it apparently was to Staughton’s student at Spelman College Alice Walker, and to so many others. Staughton had a special passion for young activist workers.

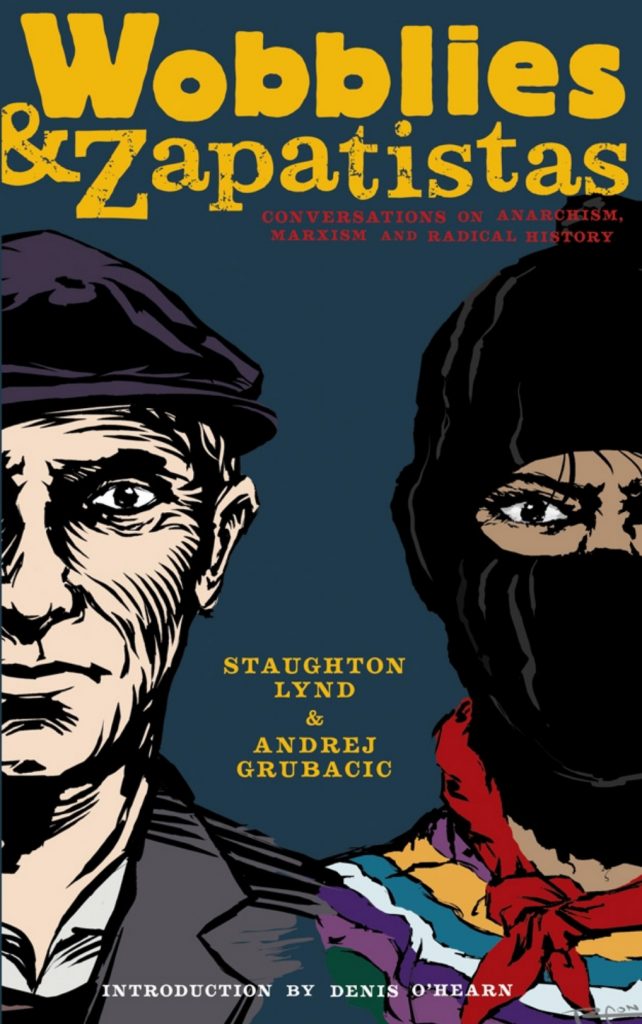

Check out these titles by Staughton Lynd