Throughout his life, Staughton Lynd affirmed that another world is possible and sought means to get from here to there. He was one of the greatest historians and libertarian socialists of our time. The Admirable Radical. Our friend. Rest in power, dear Scrapper.

Below is the excerpt of the Introduction by Andrej Grubacic from From Here to There: The Staughton Lynd Reader.

In November 2008, French academic Max Gallo argued that the great revolutionary parenthesis is closed for good. No more “magnificent barefoot men marching on a dazzled world” whom Victor Hugo had once admired. Any revolutionary transformation, Gallo said, inevitably means an eruption of violence. Because our societies are extremely fragile, the major responsibility of intellectuals and other public figures is to protect those fragile societies from such an eruption.

Gallo is hardly alone in putting forth this view, either historically or within the current moment of discussion and debate. Indeed, his cautionary plea was quickly echoed by another man of letters, and another notable French leftist, historian François Furet. Furet warned that any attempt at radical transformation was either totalitarian or terrorist, or both, and that the very idea of another society has become almost completely inconceivable. His conclusion was that we are, in a certain sense, condemned to live in the world in which we live.

And then, only one month later, in December, there was the Greek rebellion. The Greek miracle. Not a simple riot, most certainly not a “credit crunch rebellion,” but a rebellion of dignity and a radical statement of presence: of real, prefigurative, transformative and resisting alternatives. Rebellion that was about affirming the preciousness of life.

I am writing this Introduction on the anniversary of the murder of Alexis Grigoropoulos, the act that put the fire to the powder keg of the Greek December. While writing, I am reminded of words from Staughton Lynd in a personal communication written to me during those days:

At the same time, just as we honor the gifts of the Zapatistas, we should ceaselessly and forever honor the unnamed, unknown men, women and children who lay down their lives for their comrades and for a better world. There sticks in my mind the story of a Salvadoran campesino. When the death squad arrived at his home, he asked if he might put on his favorite soccer (“football”) shoes before he was shot. The path to a new world cannot be and will not be short. Any one of us can walk it only part of the way. As we do so we should hold hands, and keep facing forward.

But how do we walk? How do we begin walking?

The aim of this Introduction is to suggest the relevance of Staughton Lynd’s life and ideas for a new generation of radicals. The reader will undoubtedly notice that it has been written in a somewhat unconventional tone. My intention is to describe the process that led me, an anarchist revolutionary from the Balkans, to discover, and eventually embrace, many of the ideas espoused by an American historian, Quaker, lawyer and pacifist, influenced by Marxism. This task is not made any easier by the fact that Staughton, through the years of our friendship, has become a beloved mentor and co-conspirator. Staughton Lynd, for many good reasons that you are about to discover in reading this collection, has earned a legendary status among people familiar with his work and struggles.

It is impossible even to begin to conceive of writing a history of modern day American radicalism without mentioning the name of Staughton Lynd. He lived and taught in intentional communities, the Macedonia Cooperative Community and the Society of Brothers, or Bruderhof. He helped to edit the journal Liberation with Paul Goodman and David Dellinger. Together with Howard Zinn he taught American history at Spelman College in Atlanta. He served as director of SNCC- organized Freedom Schools of Mississippi in 1964. In April 1965, he chaired the first march against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. In August 1965, he was arrested together with Bob Moses and David Dellinger at the Assembly of Unrepresented People in Washington, D.C., where demonstrators sought to declare peace with the people of Vietnam on the steps of the Capitol. In December 1965, Staughton—along with Tom Hayden and Herbert Aptheker—made a trip to Hanoi, in hope of clarifying the peace terms of the North Vietnamese government and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam. He was one of the four original teachers at Saul Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation Training Institute founded in 1968-1969. He stands as one of the original protagonists of the New Left assertion of “history from the bottom up,” which is today so celebrated and widely appreciated. He fought as a lawyer for the rank-and-file workers of Youngstown, and for prisoners at the super- maximum security prison in Youngstown who know him as “Scrapper.” Staughton has been and remains a guru of solidarity unionism as practiced by the Industrial Workers of the World.1

This list could very easily go on. But I do not set out here to write a history of Staughton’s life. There are other books and articles that have done that.2 Rather, I would like to describe how my own politics have changed in the course of my intellectual engagement and friendship with Staughton Lynd, and why I today believe in, and continually profess the need for, a specific fusion of anarchism and Marxism, a political statement that I refused for much of my life as a militant, self-described, and unrepentant anarchist. The aim of this short Introduction is to explain why I believe that the ideas of Staughton Lynd are crucially important for the revolutionaries of my generation, and to offer some suggestions for a possible new revolutionary orientation, inspired by his ideas.

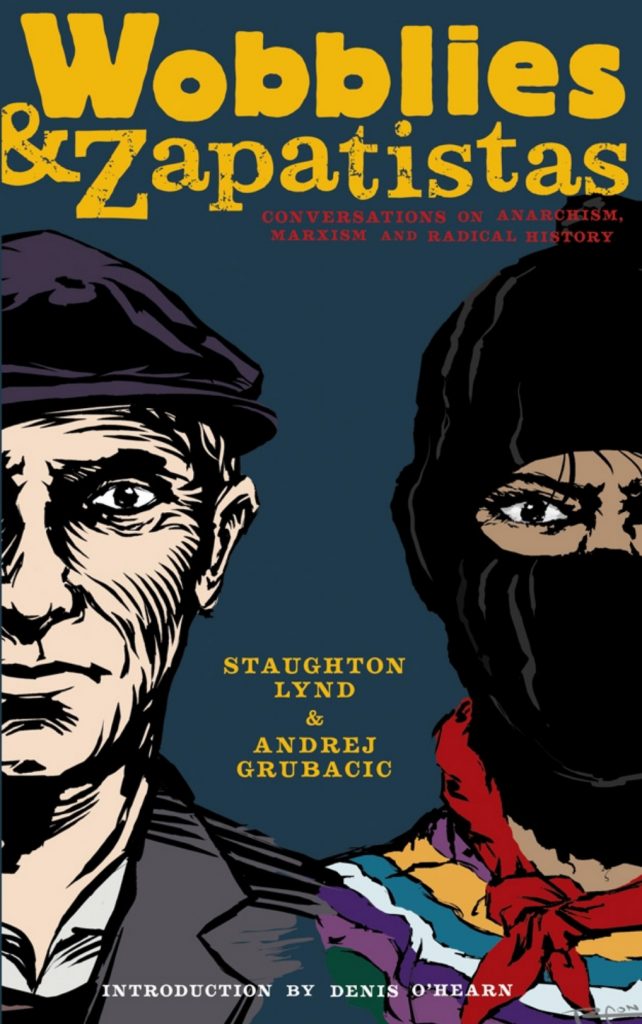

I was born to a family of revolutionaries. I come from Yugoslavia, or what is left of Yugoslavia. It is called something else now. Although I moved to the United States in 2005, I was already a foreigner well before that moment. My grandparents were socialists and Titoists, partisans and anti-fascists, dreamers who believed in self-management and the Yugoslav “path to socialism.”3 This idea—and especially the Yugoslav and Balkan dream of an inter-ethnic, pluricultural space—was dramatically dismantled in the 1990s, when I found myself living in a country that was no longer my own. It was ruled by people I could not relate to, local tyrants that we used to call “aparatciki,” bureaucrats of ideas and spirit. That was the beginning of my struggle to understand my own identity and the problem of Yugoslav socialism. I went on to look for another path to what my grandparents understood as communism. It seemed to me that the Marxist-Leninist way of getting “from here to there,” the project of seizing the power of the state, and functioning through a “democratically” centralized party organization, had produced not a free association of free human beings but a bureaucratized expression of what was still called by the official ideology of a socialist state, “Marxism.” Yugoslav self-management was, like so many other failures in our revolutionary history, a magnificent failure, a glimmer, not unlike those other ones that Staughton Lynd and I discuss in our book, Wobblies and Zapatistas.

Being thus so understandably distrustful of Marxism, I became, very early on, an anarchist. Anarchism, to my mind, means taking democracy seriously and organizing prefiguratively, that is, in a way that anticipates the society we are about to create. Instead of taking the power of the state, anarchism is concerned with “socializing”power—with creating new political and social structures not after the revolution, but in the immediate present, in the shell of the existing order. With the arrival of the Zapatistas in 1994, I dedicated all of my political energy to the emerging movement that many of us experienced as a shock of hope, and what journalists would later come to describe as a potent symbol of a new “anti-globalization movement.” With the kind help of many generous friends, I found a refuge in the United States, at the SUNY Binghamton and its Fernand Braudel Center. It is here in the libraries of New York State University, in fact, where the story of my friendship with Staughton Lynd should properly begin.

One day, as I was working in the university library—and quite by accident, or with the help of what Arthur Koestler calls library angels— my eyes were drawn to a shelf in front of me and a book with a some- what tacky cover.5 There was an American eagle, an image I did not particularly like, and a title that I was similarly not immediately fond of: Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism. This was not my cup of tea. I wanted to write about “coloniality,” post-structuralism, and other exotic things that academics seem to find interesting. As I started reading it, however, I simply could not make myself put it down. What I had in my hands was the best kind of a history-from-below: a breathtaking reconstruction of American radicalism, a moving story of anabaptists and abolitionists, of communal experiments and direct democracy, of the “ordinarily inarticulate,” a tradition of “my country is the world.” It spoke of “bicameralism from below,” a vision that is “not simply a utopian vision but a means of struggle toward that vision.” At the heart of this vision is revolution understood as a process that begins when, by demonstrations or strikes or electoral victories in the context of supplementary direct action, the way a society makes its decisions is forced to change: “That is something very real even when the beginnings are small. It means, not just that a given decision is different in substance, but that the process of decision-making becomes more responsive to the ordinarily inarticulate. New faces appear in the group that makes the decision, alternatives are publicly discussed in advance, more bodies have to be consulted. As the revolutionary situation deepens, the broadening of the decision-making process becomes institutionalized. Alongside the customary structure of authority, parallel bodies—organs of “dual power,” as Trotsky called them—arise. . . . [A] new structure of representation develops out of direct democracy and controlled by it. Suddenly, in whole parts of the country and in entire areas of daily life, it becomes apparent that people are obeying the new organs of authority rather than the old ones. . . . The task becomes building into the new society something of that sense of shared purpose and tangibly shaping a common destiny which characterized the revolution at its most

intense.” 6

These institutional improvisations are made easier if there are pre-existing organizations of the poor, institutions of their own making, such as the “clubs, the unorthodox congregations, the fledgling trade unions” that are “the tangible means, in theological language the ‘works,’ by which revolutionaries kept alive their faith that men could live together in a radically different way. In times of crisis resistance turned into revolution, the underground congregation burst forth as a model for the Kingdom of God on earth, and an organ of secular ‘dual power.’”7

I remember reading, again and again, the last passage of the book. “The revolutionary tradition is more than words and more than isolated acts. Men create, maintain, and rediscover a tradition of struggle by the crystallization of ideas and actions into organizations which they make for themselves. Parallel to Leviathan, the Kingdom is dreamed, discussed, in minuscule form established. Within the womb of the old society—it is Marx’s metaphor—the new society is born.”8

I don’t think I had ever before encountered a more lucid and beautiful description of a revolutionary process. Years later, I find myself going back to these words often. And it was this magnificent little book that ultimately made me decide to change the subject of my thesis and to write about experiences of inter-racial and inter-ethnic mutual aid in American history instead. Quite an ambitious project for a young historian from Yugoslavia to take up, and thus a further testament to the level of inspiration I drew from this book.

At its very roots, Staughton’s approach resonated with my perspective as an anarchist and how I understood anarchism. And very interestingly enough for me, this was what was drawn from the work of an explicitly self-identifying Marxist historian! But could there be a better way of writing history from the perspective of an anarchist? Is there a more apt way of being an anarchist than practicing what Staughton Lynd calls “guerrilla history” as it is described in “Guerrilla History in Gary” and “A Vision of History” (Essays 14 and 15)? And could there be a more urgent topic for someone from Yugoslavia, someone struggling to understand the intertwined legacy of inter-ethnic conflict and inter-ethnic solidarity? Soon after I put Intellectual Origins back on the shelf, I went to look for Staughton Lynd. I found him in Youngstown, Ohio.

I remember vividly our first meeting. We met in New York, a few hours before he gave the talk at the War Resisters League included in this Reader under the title, “Someday They’ll Have a War and Nobody Will Come” (Essay 24). I will never forget Staughton’s question to me: “How can I join your movement?” After a long conversation I made him the promise that I would help him to do that, but also that I would join his. Two years later, after meeting a group of young activists in Portland who were reading with excitement our Wobblies and Zapatistas, I felt I had made good on my promise.

Staughton still likes to ask me why it is that I went to see him. Why didn’t I look for some famous Italian or French radical theorist? I suspect that he knows the reason well, but I indulge him nonetheless, by answering that we all make mistakes. Still, the question deserves a longer response. After all, I was one of the activists and writers who advocated a “new anarchism”: a movement free of the burden of the traditional political practice, but rather emerging out of the organic practice of con- temporary, global and networked struggles. I penned article after article criticizing the “weight of the old.”

However, the truth is that I moved to the United States, to use an expression that Staughton likes, as a broken-hearted lover. Networks and connections that were built during the cycle of the 1990s were still in place, but 9/11 in the United States, and Genoa in Europe, as well as some profound mistakes made by the movement, brought us to a situation where there was not a coherent response to imperial globality and neo-liberal violence. The World Social Forum was in a serious crisis, and Peoples Global Action had more or less disappeared from the revolutionary horizon. Groups with which I used to work were nowhere to be found, and the global movement was in a process of a search for a new orientation. Networks were becoming not-works. It became clear to me that, at least in the long term, we should not anchor our efforts in the hope for encounters and summits. The lifestyle of activists who “summit hop” from one brief-lived action to the next is, in the long run, unsustainable. There was a need for a new emancipatory program. It was my feeling that in running away from traditional models of organizing we ended up running too far, and far too quickly.

The whole context that David Graeber and I optimistically described as a coalescing “new anarchism” was in a state of evident con- fusion.9 Even today, in times that are perceived by most as a serious crisis of the capitalist system, the movement in the United States is still far from having achieved any strategic clarity. The Left is without the movement. Or the movement is without the Left. Wobblies and Socialists are not organizing “encampments” in rural Oklahoma, as they used to do before the inter-racial Green Corn Rebellion of 1917. Times are as serious as they were then, if not more so, but somehow there are no “penny auctions” this time around. Meanwhile, intellectuals are writing serious political essays that no one who hasn’t spent years in graduate school can hope to understand. Ivy league professors are telling us that to hope and work for an inter-racial movement is a waste of time. White workers are irrevocably generalized as racists, class is “multitude,” and we are all part of the post-alpha generation suffering from the pathologies of “semiocapitalism.”

On the other side of the world, news from Yugoslavia, or whatever other name local elites and foreign embassies now use to describe it, was and remains equally disconcerting. I was an outsider trying to make sense, from the outside, of what has happened to my movement and to the country from which I came. I felt we needed a revolutionary synthesis of a new kind. That is why I went to find Staughton Lynd. I went to Youngstown to listen, to try to understand what went wrong, and I found myself in a conversation.

In the forthcoming years of our friendship and intellectual partner- ship, we came up with a suggestion for a new revolutionary orientation that would be premised on a fusion, or synthesis, of what we recognized as indispensable qualities of both anarchism and Marxism. It would perhaps be accurate to say that, in the process, I became a bit of a Marxist and Staughton a bit of an anarchist. In Wobblies and Zapatistas, we offered the following approach:

“What is Marxism? It is an effort to understand the structure of the society in which we live so as to make informed predictions and to act with greater effect. What is anarchism? It is the attempt to imagine a better society and insofar as possible to “prefigure,” to anticipate that society by beginning to live it out, on the ground, here and now. Isn’t it perfectly obvious that these two orientations are both needed, that they are like having two hands to accomplish the needed task of transformation? These two viewpoints had been made to seem to be mutually exclusive alternatives. They are not. They are Hegelian moments that need to be synthesized.” 10

These two viewpoints had been made to seem to be mutually exclusive alternatives. They are not. They are Hegelian moments that need to be synthesized.

We argued that in North America there is a tradition we termed the Haymarket synthesis, a tradition of the so-called “Chicago school” of anarchism, represented by Albert Parsons, August Spies, and the other Haymarket martyrs, all of whom described themselves as anarchists, socialists, and Marxists. This tradition was kept alive by the magnificent band of rebels known as the Wobblies, and today by rebels in Chiapas, the Zapatistas. Our responsibility today, in the United States, is to revive the Haymarket synthesis, to infuse it with new energy, new passion and new insights. To discover libertarian socialism for the twenty-first century. To rekindle dreams of a “socialist commonwealth,” and to bring socialism, that “forbidden word,” into a new and contemporary meaning. It is my belief that the ideas collected in the Reader before you present an important step in this direction. They suggest a vision of a libertarian socialism for the twenty-first century organized around the idea and practice of solidarity.

The essays in this collection do not tell us about one and only one way of getting “from here to there.” As Staughton writes in “Toward Another World” (Essay 25), “I am glad that there does not exist a map, a formula or equation within which we must act to get from Here to There. It’s more fun this way, to move forward experimentally, some- times to stumble but at other times to glimpse things genuinely new, always to be open to the unexpected and the unimagined and the not- yet-fully-in-being.”

In this spirit, without offering or imposing blueprints, I would like to suggest that libertarian socialism for the twenty-first century, a contemporary reworking of the Haymarket synthesis, could be organized around three important themes:

1. Self-activity. In creating a libertarian socialism for the twenty- first century we should rely not on a fantasy that salvation will come from above, but on our own self-activity expressed through organizations at the base that we ourselves create and control.

2. Local institutions or “warrens.” Crucially important for a new revolutionary orientation is what Edward Thompson called a warren, that is, a local institution in which people conduct their own affairs.

3. Solidarity. We need to build more than a movement, we need to build a community of struggle.

1. Self-actIvIty

We can understand self-activity in two ways. One is through what the Industrial Workers of the World call “solidarity unionism.” In different parts of this Reader, Staughton describes solidarity unionism as a horizontal expression of workers’ self-activity. In “Toward Another World” (Essay 25), he explains:

An easy way to remember the basic idea of solidarity unionism is to think: Horizontal not vertical. Mainstream trade union- ism beyond the arena of the local union is relentlessly vertical. Too often, rank-and-file candidates for local union office imagine that the obvious next step for them is to seek higher office, as international union staff man, regional director, even international union president. The Left, for the past seventy- five years, has lent itself to the fantasy that salvation will come from above by the election of a John L. Lewis, Philip Murray, Walter Reuther, Arnold Miller, Ed Sadlowski, Ron Carey, John Sweeney, Andrew Stern, or Richard Trumka.

Instead we should encourage successful rank-and-file candidates for local union office to look horizontally to their counterparts in other local unions in the same industry or community. This was labor’s formula for success during its most creative and successful years in memory, the early 1930s. During those years there were successful local general strikes in Minneapolis, Toledo, San Francisco, and other, smaller industrial towns. During those years local labor parties sprang up like mushrooms across the United States. Today some organizers in the IWW, for example in Starbucks stores in New York City, once again espouse solidarity unionism.

Instead of following the top-down, bureaucratic traditions of the founding fathers of the labor movement, and their fascination with national unionism, we should follow another path, the one that, as Staughton points out in “From Globalization to Resistance” (Essay 19), “takes its inspiration from the astonishing recreation from below throughout the past century of ad hoc central labor bodies: the local workers’ councils known as ‘soviets’ in Russia in 1905 and 1917; the Italian factory committees of the early 1920s; solidarity unions in Toledo, Minneapolis, San Francisco, and elsewhere in the United States in the early 1930s; and similar forma- tions in Hungary in 1956, Poland in 1980-1981, and France in 1968 and 1995.” What is important, he explains, is that these “were all horizontal gatherings of all kinds of workers in a given locality, who then form re- gional and national networks with counterpart bodies elsewhere.”

A second form of self-activity, closely related to the practice of soli- darity unionism, is the Mayan idea of “mandar obediciendo” that informs the contemporary practice of the Zapatistas. This vision of a government “from below” that “leads by obeying” calls for separate emphasis, as Lynd says in his concluding essay, “because of the preoccupation of socialists for the past century and a half with ‘taking state power.’” As I read the communiques from the Lacondón jungle, he writes, “I realized that at least from a time shortly after their initial public appearance, the Zapatistas were saying: We don’t want to take state power. If we can create a space that will help others to make the national government more democratic, well and good. But our task, as we see it, is to bring into being self-governing local entities linked together horizontally so as to present whoever occupies the seats of government in Mexico City with a force so powerful that it becomes necessary to govern in obedience to what Subcomandante Marcos calls ‘the below.’”

What the Zapatistas mean by this is an intention, an active effort to create and maintain a horizontal network of self-governing communities. This is what a new kind of libertarian socialism would look like. As Staughton writes on the last page of Wobblies and Zapatistas: “imagining a transition that will not culminate in a single apocalyptic moment but rather express itself in unending creation of self-acting entities that are horizontally linked is a source of quiet joy.”11

2. Local Institutions or “warrens””

As for warrens, in “Edward Thompson’s Warrens” (Essay 21)—one of the most important pieces in this collection—we learn about a metaphor that is central to Thompson’s understanding of a revolutionary pro- cess: a rabbit warren, that is, a long-lasting local institution. I remember once reading somewhere about a Spanish revolutionary and singer who said that we lost all the battles, but we had the best songs. I never liked this attitude, as noble and poetic as it might be. Any new revolutionary perspective ought to go beyond this. For much of my life as a revolution- ary I have been haunted by what I call “Michelet’s problem.” Michelet was a famous French historian, who wrote the following words about the French revolution: “that day everything was possible, the future was the present and time but a glimmer of eternity.” But, as Cornelius Castoriades used to say, if all that we create is just a glimmer of hope, the bureaucrats will inevitably show up and turn off the light.12 The history of revolutions is, on the one hand, a history of tension between brief moments of revolutionary creativity and the making of long-lasting institutions. On the other hand, the history of revolutions often reads like a history of revolutionary alienation, when the revolutionary was, more than anything else, ultimately and almost inevitably alienated from his or her own creations. Michelet’s problem is about resolving this tension between brief epiphanies of revolutionary hope and the hope for long-term institutionalization of revolutionary change.

The crucial question then is how to create such lasting institutions, or better yet, an ongoing culture of constructive struggle. In Wobblies and Zapatistas, Staughton asserts that “every single one of the ventures or experiments in government from below that we have been discussing existed for only a few months or years. In many societies they were drowned in blood. In most cases underlying economic institutions, that provided the matrix within which all political arrangements functioned, did not change. The leases on Hudson Valley manors after the Revolution did not differ dramatically from such leases before the Revolution.”13 So what is missing? How can we try to approach the answer to what I have called Michelet’s problem?

In the contemporary anarchist movement, if we can speak of one, there is a lot of talk about “the insurrection” and considerable fascination with “the event.”14 The French accent and sophisticated jargon are perhaps new and in fashion, but these are not new topics. They appear to crop up, with disturbing regularity, with every new generation of revolutionaries. The old refrain that organizing is another word for going slow is being rediscovered by some of the new radicals. This is the topic of “The New Radicals and Participatory Democracy” and, especially, “Weatherman” (Essays 6 and 8).

I think we can say that there are, risking some oversimplification, two ways of thinking about revolution. In his essay on Thompson’s warrens, Staughton says that “Thompson implicitly asks us to choose between two views of the transition from capitalism to socialism.” One is expressed in the song “Solidarity Forever” when the song affirms, “We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.” In this perspective, “the new world will arise, phoenix-like, after a great catastrophe or conflagration. The emergence of feudalism from pockets of local self- help after the collapse of the Roman Empire is presumably the exemplar of that kind of transition.” This is the negative idea of revolution, very much present in contemporary movement literature.15

A second view of the revolution is positive, comparing it to the transition from feudalism to capitalism.

The preamble to the IWW Constitution gives us a mantra for this perspective, declaring that “we are forming the structure of the new society within the shell of the old.”

Thompson opted for the second paradigm. . . . For a society to be criss-crossed by underground dens and passageways created by an oppositional class is, in Thompson’s 1960s vocabulary, to be “warrened.” British society, he wrote, is “warrened with democratic processes—committees, voluntary organizations, councils, electoral procedures.” Because of the existence of such counter-institutions, in Thompson’s view a transition to socialism could develop from what was already in being, and from below. “Socialism, even at the point of revolutionary transition—perhaps at this point most of all—must grow from existing strengths. No one . . . can impose a socialist humanity from above.”

We have here an image of a constructive, not apocalyptic, revolution: built on the positives of a socialist commonwealth emerging from existing creations improvised from below. In Thompson’s words:

[S]uch a revolution demands the maximum enlargement of positive demands, the deployment of constructive skills within a conscious revolutionary strategy—or, in William Morris’ words, the “making of Socialists.” . . . Alongside the industrial workers, we should see the teachers who want better schools, scientists who wish to advance research, welfare workers who want hospitals, actors who want a National Theatre, technicians impatient to improve industrial organization. Such people do not want these things only and always, any more than all industrial workers are always “class conscious” and loyal to their great community values. But these affirmatives exist, fitfully and in- completely, with the ethos of the Opportunity State. It is the business of socialists to draw the line, not between a staunch but diminishing minority and an unredeemable majority, but between the monopolists and the people—to foster the “societal instincts” and inhibit the acquisitive. Upon these positives, and not upon the debris of a smashed society, the socialist community must be built.

We should always cherish these beautiful words. But what is Thompson’s warren? And why do I insist that it represents a formula for success? It is, first and foremost, a local institution in which people conduct their own affairs—an immigrant center or local union, for example—that expands in time of crisis to take on new powers and responsibilities, and then, after the revolutionary tide ebbs, continues to represent, in institutionalized form, an expanded version of what existed to begin with.

It would be impossible to understand the Russian revolution—the long Russian revolution (from 1890 to 1920)—without looking at the middle-class convocations, the student demonstrations, the workers’ petitions: all forms of direct action, within the context of pre-existing and new “warrens,” such as local unions, universities, and soviets. After the failure of the December 1905 uprising in Moscow and Petrograd, soviets lived on in popular memory until they were re-created by workers in 1917. In American labor history the most important meetings and organizations, including the ones that led to formation of the CIO in the 1930s, took place in pre-existing local institutions, such as fraternal societies, credit unions, burial associations, singing clubs, churches and newspapers.

In “Remembering SNCC” (Essay 4), an essay that ought to become required reading for anyone interested in the movement of the Sixties, we discover that one cannot hope to understand what happened in the South and in the civil rights movement without understanding that stu- dent action emerged from pre-existing warrens such as African American churches and college campuses. In the last section of the Reader, we learn that the Zapatistas provide perhaps the clearest example of all: hundreds if not thousands of years of life in pre-existing asambleas, and a decade of as yet unchronicled “accompaniment” by a group of Marxists-Leninists from the universities of Mexico City.

A way of looking at what happened in all these cases is that revolutionaries can often light a spark—not a prairie fire!—but whether or not a fire will catch on depends on the response of people in their pre- existing local unions, factory committees, benefit associations, and other local institutions. Some of the self-governing institutions will be old entities (warrens) that have taken on new powers and objectives. In Chiapas, Mayan asambleas play this role. In Russia, soviets were the heart of the revolution. The nature of a revolutionary process is such that the distinction between old and new local institutions becomes blurred. The role of libertarian socialists is above all to nurture the creation, the spread, and the authority of local “warrens,” to defend the existence, the legitimacy, and the autonomy of such formations.

3. Solidarity

Finally, how do we do that? How do we build communities of struggle?

If capitalism developed as a practice of the idea of contract, libertarian socialism should be developed as a practice of solidarity. There are several kinds of solidarity. On the one hand, we might say, solidarity can be defined as drawing the boundary of our community of struggle as widely as possible. There are many examples of solidarity thus defined. In “Henry Thoreau: The Admirable Radical” (Essay 1) and especially in “The Tragedy of American Diplomacy” (Essay 23), Staughton speaks very fondly of Thoreau, who, in his essay on civil disobedience, famously observed that the fugitive slave, and the Mexican prisoner on parole, and the Indian come to plead the wrongs of his race, should find good citizens in the only house in a slave state in which a free man can abide with honor, namely, in prison behind bars.

This is one way of understanding solidarity. Another way of understanding solidarity is by pointing out, as Staughton does in his essay “From Globalization to Resistance” (Essay 19), is that there is a problem with the concept of organizing. There are several ways to organize. One way is Leninist vanguardism: the idea that the working class, left to itself, is able to develop only trade-union consciousness. The proper revolutionary consciousness could only be brought to workers “from without.” In the United States, during the 1930s and 1970s, this process was known as “colonization.” Revolutionaries would go to a factory and “colonize” the workplace. It is not all that different with trade-union organizers, irrespective of how courageous or resourceful they might be: when they organize in a way that implicitly assumes an “outside,” it creates a certain inequality between organizer and organized.

The anarchist response to this, in the last couple of decades, was twofold. One way was to offer a perspective of “contaminationism.” As David Graeber explains, “On a more immediate level, the strategy depends on the dissemination of the model: most anarchists, for example, do not see themselves as a vanguard whose historical role is to ‘organize’ other communities, but rather as one community setting an example others can imitate. The approach—it’s often referred to as ‘contaminationism’—is premised on the assumption that the experience of freedom is infectious: that anyone who takes part in a direct action is likely to be permanently transformed by the experience, and want more.”16

The other, loosely-defined anarchist approach was to behave like a social worker, tending the communities from the outside, not as a fellow student or a fellow worker with a particular understanding of a situation shared with others, but as an “activist” or professional in social change—a force outside of society, organizing those “inside” on their own behalf. There are many successful and admirable examples of this kind of organizing. However, the same problem of implicit inequality still stands.

A far better alternative than these two responses, and one that I would like to advance here, is a process that Staughton calls “accompaniment.” Revolutionaries should accompany workers and others in the creation and maintenance of popular self-governing institutions. In this process, we should not pretend to be something we are not. Rather, we can walk beside poor people in struggle just as we are, hopefully providing support and certain useful skills.

I experienced this vision of accompaniment while I was still living in Yugoslavia. A few of us, students from Belgrade University, recognized that the only organized resistance to the encroaching tide of privatization and neo-liberalism was coming from a group of workers in the Serbian countryside. We decided to go to northern Serbia, to a city called Zrenjanin, and approach the workers. These workers were very different from ourselves. Some of them had fought in the recent Yugoslav wars. Most of them were very conservative, patriarchal, and traditional. We went there and offered our skills. We had a few. We spoke foreign languages. We had internet access and know-how in a country where only two percent of the people used this service. We had connections with workers and movements outside Serbia. Some were good writers. A few had legal expertise. These workers were grateful but understandably quite skeptical, as were we. Soon, however, something like a friendship emerged. We started working together and learning from each other. In the process of struggling against the boss, the private armies he sent to the factory, and the state authorities, we started to trust each other. We both changed—workers and students.

Staughton and his wife Alice encountered the notion of accompaniment in Latin America. In “From Globalization to Resistance” (Essay 19), we find these lines:

In Latin America—for example, once again, in the work of Archbishop Romero—there is the different concept of “accompaniment.” I do not organize you. I accompany you, or more precisely, we accompany each other. Implicit in this notion of “accompañando” is the assumption that neither of us has a complete map of where our path will lead. In the words of Antonio Machado: “Caminante, no hay camino. Se hace camino al andar.” “Seeker, there is no road. We make the road by walking.”

Accompaniment has been, in the experience of myself and my wife, a discovery and a guide to practice. Alice first formu- lated it as a draft counselor in the 1960s. When draft counselor meets counselee, she came to say, there are two experts in the room. One may be an expert on the law and administrative regulations. The other is an expert on what he wants to do with his life. Similarly as lawyers, in our activity with workers and prisoners, we have come to prize above all else the experience of jointly solving problems with our clients. They know the facts, the custom of the workplace or penal facility, the experi- ence of past success and failure. We too bring something to the table. I do not wish to be indecently immodest, but I will share that I treasure beyond any honorary degree actual or imagined the nicknames that Ohio prisoners have given the two of us: “Mama Bear” and “Scrapper.”

In “Toward Another World” (Essay 25), Staughton writes:

“In the annual pastoral letters that he wrote during the years before his assassination, Romero projected a course of action with two essential elements. First, be yourself. If you are a believing Christian, don’t be afraid of professing it. If you are an intellectual don’t pretend that you make your living by manual labor. Second, place yourself at the side of the poor and oppressed. Accompany them on their journey.. . . One last point about accompaniment is that it can only come about if you—that is, the lawyer, doctor, teacher, clergyman, or other professional person—stay in the community over a period of years. . . . I feel strongly that if more professionals on the Left would take up residence in communities other than Cambridge, New York City, and Berkeley, and stay there for a while, social change in this country might come a lot more quickly.”

. . . One last point about accompaniment is that it can only come about if you—that is, the lawyer, doctor, teacher, clergyman, or other professional person—stay in the community over a period of years. . . . I feel strongly that if more professionals on the Left would take up residence in communities other than Cambridge, New York City, and Berkeley, and stay there for a while, social change in this country might come a lot more quickly.

“The Two Yales” (Essay 12) and “Intellectuals, the University and the Movement” (Essay 13) are perhaps the most radical critique of the arrogance of campus intellectuals I ever came across. In Wobblies and Zapatistas, Staughton added:

I have a hard time with theorizing that does not appear to arise from practical activity or lead to action, or indeed, that seems to discourage action and consider action useless.

I don’t think I am intellectually inept. Yet I confess that much of what is written about “post-Marxism,” or “Fordism,” or “deconstruction,” or “the multitude,” or “critical legal studies,” or “whiteness,” and that I have tried to read, seems to me, simply, both unintelligible and useless.

What is the explanation for this universe of extremely abstract discourse? I yearn to ask each such writer: What are you doing? With what ordinary people do you discuss your ideas before you publish them? What difference does it make, in the world outside your windows and away from your word processor, whether you say A or B? For whom do you consider yourself a model or exemplar? Exactly how, in light of what you have written, do you see your theoretical work leading to another world? Or would it be more accurate to suggest that the practical effect of what you write is to rationalize your comfortable position doing full-time theorizing in a college or university?17

In the pages of the same book Staughton offers a similarly trenchant critique of some anarchist practices:

As a lifelong rebel against heavy-handed Marxist dogmatism I find myself defending Marx, and objecting to the so-called radicalism of one-weekend-a-year radicals who show up at a global confrontation and then talk about it for the rest of the year.

These are harsh words. But I consider them deserved. Anarchists, above all others, should be faithful to the injunction that a genuine radical, a revolutionary, must indeed swim in the sea of the people, and if he or she does not do so, is properly viewed as what the Germans called a “socialist of the chair,” or in English, an “armchair intellectual.”

It is a conspiracy of persons who make their living at academic institutions to induce others who do the same to take them seriously. I challenge it and reject it. Let them follow Marcos to the jungles of Chiapas in their own countries, and learn something new.18

In this project of “accompaniment,” the model should be that of the Mexican intellectuals, students and professors, who went to live in the jungle, and after ten years came forth as protagonists of a revolution from below. The Zapatistas were not footloose: they went to a particular place and stayed there, in what must have been incredibly challenging and difficult circumstances, for a decade of accompaniment. The central component of accompaniment is that we should settle down in particular places so that when crises come we will already be trusted friends and members of the community.

When I argue for accompaniment in my university talks I am usually accused of proposing a practice that defers, without criticism, to whatever poor and oppressed people in struggle believe and are demand- ing at the moment. It is to these critiques that Staughton answers in Wobblies and Zapatistas:

In his fourth and last Pastoral Letter, written less than a year before his death, Romero says that the preferential option for the poor does not mean “blind partiality in favor of the masses.” Indeed:

In the name of the preferential option for the poor there can never be justified the machismo, the alcoholism, the failure in family responsibility, the exploitation of one poor person by another, the antagonism among neighbors, and the so many other sins that [are] concurrent roots of this country’s crisis and violence.

I submit that the foregoing is hardly a doctrine of un- thinking subservience to the momentary beliefs or instructions of the poor.

I challenge those who offer this critique of “accompaniment” to explain, in detail, how they go about relating to the poor and oppressed. I suspect that they do not have such relationships at all. That makes it easy to be pure: without engagement with the world, one need only endlessly reiterate one’s own abstract identity.

“Accompaniment” is simply the idea of walking side by side with another on a common journey. The idea is that when a university-trained person undertakes to walk beside someone rich in experience but lacking formal skills, each contributes something vital to the process. “Accompaniment” thus under- stood presupposes, not uncritical deference, but equality.19

It is interesting to note the similarity between accompaniment and another form of praxis emerging from Latin America. In some parts of the continent anarchists have developed a praxis of involvement in social movements that they call “Especifismo.” The mainstay of Especifismo is the engagement called “social insertion.” This means activists being focused on activity within, and helping to build, mass organizations and mass struggles, in communities and neighborhoods, in various social spheres. This does not mean people from outside intervening in struggles of working people, but is about the focus of organizing radicals within the communities of struggle. Various struggles can include strikes, rent strikes, struggles for control of the land, struggles against the police and gentrification, struggles against sexism, for the right to abortion, against bus fare increases, or any other issue that angers working people and moves them to act.20

But accompaniment can be taken even further, to the very issue of revolutionary agency. In “From Globalization to Resistance” (Essay 19) we encounter a hypothesis, further developed in “Students and Workers in the Transition to Socialism” (Essay 20), that the concept of “accompaniment,” in addition to clarifying the desirable relationship of individuals in the movement for social change to one another, also has application to the desirable relationship of groups. A great deal of energy has gone into defining the proper relationship in the movement for social change of workers and students; blacks and whites; men and women; straights and gays; gringos, ladinos and indígenas; and no doubt, English-speakers and French-speakers. An older wave of radicalism struggled with the supposed leading role of the proletariat. More recently other kinds of division have preoccupied us. My question is, what would it do to this discussion were we to say that we are all accompanying one another on the road to a better society?

It appears that in Hungary, as well as later in France and the United States, and before that in revolutionary Russia, students came first, and workers subsequently joined in.

Why do students so often come first? One can speculate. To whatever extent Gramsci is right about the hegemony of bourgeois ideas, students and other intellectuals break through it: they give workers the space to think and experience for themselves. Similarly, the defiance of students may help workers to overcome whatever deference they may be feeling toward supposed social superiors.

It is of great importance to stress that solidarity must be built out- side of the university library and on the basis of practice, not shared ideas. Solidarity only can be built on the basis of action that is in the common interest. In the pages of “Nonviolence and Solidarity” (Essay 17) we learn that in “the world of poor and working-class resistance . . . action often comes before talk, and may be in apparent contradiction to words that the actor has used, or even continues to use in the midst of action. The experience of struggle gives rise to new understandings that may be put into words much later or never put into words at all.” In these situations, “Experience ran ahead of ideology. Actions spoke louder than organizational labels.”

The most convincing example of this is the prison uprising at Lucasville, Ohio, a rebellion inside a maximum security prison which Staughton discusses in “Overcoming Racism” (Essay 18).21

The single most remarkable thing about the Lucasville rebellion is that white and black prisoners formed a common front against the authorities. When the State Highway Patrol came into the occupied cell block after the surrender they found slogans written on the walls of the corridor and in the gymnasium that read: “Convict unity,” “Convict race,” “Blacks and whites together,” “Blacks and whites, whites and blacks, unity,” “Whites and blacks together,” “Black and white unity.”

The five prisoners from the rebellion on death row—the Lucasville Five—are a microcosm of the rebellion’s united front. Three are black, two are white. Two of the blacks are Sunni Muslims. Both of the whites were, at the time of the rebellion, members of the Aryan Brotherhood.

Could Lucasville’s example provide us with glimpses of how to create an interracial movement?

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the self-organized protest movement of blacks created a model for students, women, workers, and eventually, soldiers. In the same way, the self- organized resistance of black and white prisoners can become a model for the rest of us in overcoming racism. Life will continue to ask of working people that they find their way to solidarity. Surely, there are sufficient instances of deep attitudinal change on the part of white workers to persuade us that a multi-ethnic class consciousness is not only necessary, but also possible.

This is one of the aspects of Staughton’s thought that influenced me the most. I started exploring American history and, while falling short of discovering many examples of a “usable past,” I was able to discern a current of inter-racial, inter-ethnic mutual aid that we could follow from the early days on the frontier to the interracial unionism of the Wobblies in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, SNCC, and Lucasville. The important thing is not to romanticize these experiences. A legacy of conquest and a legacy of mutual aid co-exist in American history and American politics, just as they do in the Balkans. A new anti-capitalist inter-racial movement is possible only in the context of practical, lived solidarity, that transcends and overcomes differences. Libertarian social- ism for the twenty-first century needs to be built on the understanding that the only movement worthy of that name is an inter-racial movement built on the process of accompaniment.

What about solidarity in the context of internationalism? In Intellectual Origins Staughton explores the tradition articulated by a series of working-class intellectuals in the United States whose credo was, “My country is the world.” In one of the most beautiful passages of Wobblies and Zapatistas, Staughton says the following:

Surely this is the form of internationalism we should espouse. It makes it possible for us to say, “Yes, I love my country! I love the fields of New England and Ohio, and also the mist- covered mountains and ravines of Chiapas and Nicaragua. I love the clarity of Thoreau, the compassion of Eugene Debs and the heroism of Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the paintings of Rembrandt, the music of Bach. I admire the conductors of the Underground Railroad and the self-organizing peasants and artisans in revolutionary Spain. My country is the world.”

Finally, there is another kind of solidarity, one that must be nurtured not only in struggle but in our communities of struggle. This is very hard but necessary. If we can’t build an organization in which human beings trust one another as brothers and sisters, why should anyone trust us to build a better society? Within the pages of Wobblies and Zapatistas, Staughton urges:

“We need to proceed in a way that builds community. There must be certain ground rules. We should practice direct speaking: if something bothers you about another person, go speak to him or her and

do not gossip to a third person. No one should be permitted to present themselves in caucuses that define a fixed position beforehand and are impervious to the exchange of experiences. We must allow spontaneity and experiment without fear of humiliation and disgrace. Not only our organizing but our conduct toward one another must be paradigmatic in engendering a sense of truly being brothers and sisters.”

In my years as an anarchist organizer, one of the most disturbing patterns I noticed is exactly the problem Staughton describes here: the inability to practice comradeship to keep our networks, our social centers and affinity groups alive. I would see one group after another destroyed by corrosive suspicion and distrust. In order for us to be effective as revolutionaries, our communities of struggle must become affective communities—places where we practice direct dialogue and prefigurative relationships.

The new generation of revolutionaries has a huge responsibility today, most of all in the current crisis of capitalist civilization. We need to muster imagination and prefigurative energy to demonstrate that radical transformation of society is indeed possible, despite the words of those two distinguished professors mentioned at the beginning of this Introduction. Forr this we need a new kind of synthesis. Perhaps the one that I tried to propose: a reinvented and solidarity-centered libertarian socialist synthesis that combines direct democracy with solidarity unionism. Strategy with program, accompaniment with warrening, structural analysis with prefigurative theory arising from practice; stubborn belief in the possibility of overcoming racism with affective anti-sectarianism. This proposed synthesis is, perhaps, woefully inadequate, simplistic or naive. Even if this is so—even if this is not that map which will take us safely from here to there—I hope that it can at least provoke and inspire a conversation moving toward these ends and ideals.

George Lukács ends his book, Theory of the Novel, with the sentence, “the voyage is over, now the travel begins.” This is what happens at the moment when the revolutionary glimmer has been extinguished: the voyage of a particular revolutionary experience may be over, but the true journey is just starting. At this very moment, I hear that the Polytechnic school in Athens has been occupied once again. People are in the streets. The spirit of December, one year after the rebellion, is everywhere.

Marxist political economists say that capitalist civilization is crumbling. This might be so. If it is, good riddance. We should hear the voice of Buenaventura Durruti speaking to us, across decades, that we should not be in the least afraid of its ruins. But the path to a new world that we carry in our hearts, a path to a free socialist community, can be built only on existing strengths, on practices of everyday communism and mutual aid, and not “upon the debris of a smashed society.” Upon the positives, with our collective prefigurative creativity, we should venture to re-make another world. It is indeed a long journey. But as Staughton Lynd never ceases to remind us—as we walk we should hold hands, and keep facing forward.

endnotes

1 Because of his advocacy and practice of civil disobedience, Staughton was unable to continue as a full-time history teacher. The history departments of five Chicago-area universities offered him positions, only to have the offers negated by the school administrations. In 1976, Staughton became a lawyer. He worked for Legal Services in Youngstown, Ohio from 1978 until his retire- ment at the end of 1996. He specialized in employment law, and when the steel mills in Youngstown were closed in 1977-1980 he served as lead counsel to the Ecumenical Coalition of the Mahoning Valley, which sought to reopen the mills under worker-community ownership and brought the action Local 1330 v. U.S. Steel. He has written, edited, or co-edited with his wife Alice Lynd more than a dozen books. The Lynds have jointly edited four books. They are Homeland: Oral Histories of Palestine and Palestinians (New York: Olive Branch Press, 1994); Nonviolence in America: A Documentary History, revised edition (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1995, now in its sixth printing); Rank and File: Personal Histories by Working-Class Organizers, third edition (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1988); and, most recently, The New Rank and File (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000), which includes oral histories of labor activists in the past quarter century. Their memoir of life together is published under the title Stepping Stones (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009).

2 See especially Carl Mirra, The Admirable Radical: Staughton Lynd and Cold War Dissent, 1945-1970 (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2010).

3 See my book Don’t Mourn, Balkanize (Oakland: PM Press, 2010).

4 A very good introduction to the anti-globalization movement is News from Nowhere, We Are Everywhere (New York: Verso, 2004).

5 Staughton Lynd, Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism, new edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

6 Intellectual Origins, pp. 171-172.

7 Intellectual Origins, p. 173.

8 Ibid.

9 David Graeber and Andrej Grubacic, “Anarchism, or the

Revolutionary Movement of the Twenty-first Century,” http://www.zmag.org/ znet/viewArticle/9258.

10 Staughton Lynd and Andrej Grubacic, Wobblies & Zapatistas:

26 From Here to There

Conversations on Marxism, Anarchism and Radical History (Oakland: PM Press, 2008), p. 12.

11 Wobblies & Zapatistas, p. 241.

12 Cornelius Castoriadis, Political and Social Writings (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), p. 131.

13 Wobblies & Zapatistas, p. 81.

14 See Invisible Committee, The Coming Insurrection (Los Angeles: Semiotext(e), 2009).

15 See Derrick Jensen, A Language Older than Words (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2004).

16 David Graeber, Direct Action: An Ethnography (Oakland: AK Press,

2009).

17 Wobblies & Zapatistas, p. 215.

18 Wobblies & Zapatistas, p. 23.

19 Wobblies & Zapatistas, p. 176.

20 See Michael Schmidt and Lucien Van Der Walt, Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism (Oakland: AK Press,2009).

21 Staughton Lynd has written about the Lucasville rebellion in “Black and White and Dead All Over,” Race Traitor, no. 8 (Winter 1998); “Lessons from Lucasville,” The Catholic Worker, v. LXV, no. 7 (Dec. 1998); and “The Lucasville Trials,” Prison Legal News, v. 10, no. 6 ( June 1999). This work is gathered together in Lucasville: The Untold Story of a Prison Uprising (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004). Staughton has also contributed to a play by Gary Anderson about the Lucasville events.

Check out these titles by Staughton Lynd