By Erik Gunn

Wisconsin Examiner

September 27th, 2022

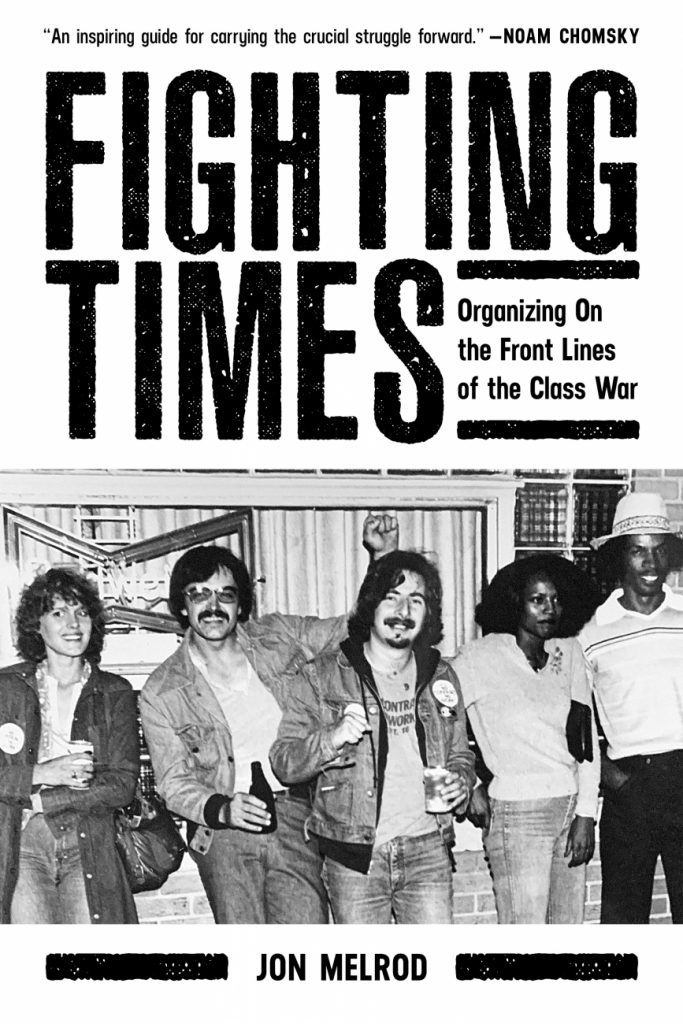

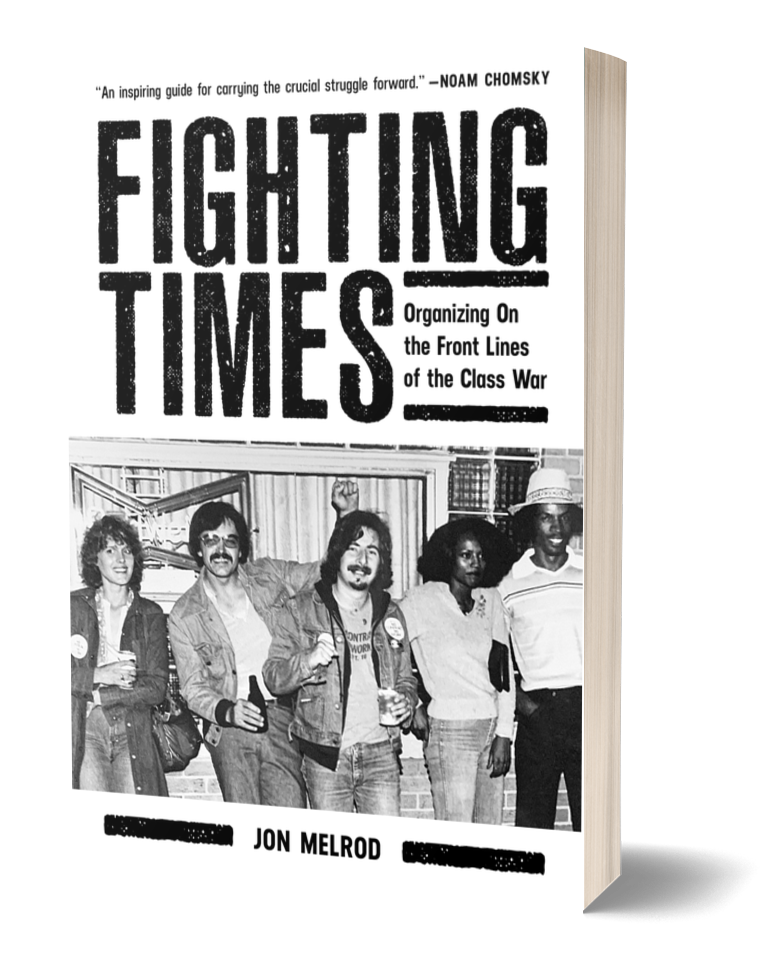

Jon Melrod has written a memoir that tells a slice of labor history in Kenosha, Wisconsin, four decades ago. But he believes his story, “Fighting Times,” which goes on sale Tuesday, has broader appeal.

“It’s everybody’s story — everybody who’s ever worked, who’s ever worked for a bad boss or under bad conditions,” said Melrod, a one-time autoworker who went on to become a human rights lawyer.

Amazon workers seeking union representation have talked about having to urinate in plastic bottles because they were denied bathroom breaks.

“Well, there’s an episode in my book where a probationary employee couldn’t get a break to go to the bathroom, and he urinated in his pants,” Melrod said in an interview. “And his entire line stopped working to protest it.”

Melrod came to unionism through social activism that started in his teens.

He didn’t come from wealth; his father clawed his way from work selling shoes to become a self-taught attorney. Growing up in Washington, D.C. in the early 1960s, Melrod saw racism close at hand: a chain gang of incarcerated Black men that his family passed on an afternoon drive, or the segregated amusement park that admitted Blacks only after students from Howard University staged a picket line and white segregationists responded with violence.

With striving ambition, his parents sent him to a Vermont boarding school, where in his teens Melrod gravitated toward the civil rights movement and the emerging resistance to the Vietnam war and the draft.

At the University of Wisconsin, Melrod threw himself into the erupting opposition to the war. He volunteered with organizers for Obreros Unidos, a union working on behalf of Hispanic farmworkers in Wisconsin.

He was a witness and participant in the February 1969 strike by Black students to call attention to the disparities they faced — 1% of a student body that was 99% white. As many as 12,000 students — nearly one-third of the student body — took part in a march on the state Capitol at the pinnacle of the confrontation. The vast majority were white.

“They jeopardized their educations to support demands that expressly and solely addressed the historical disparity faced by Blacks at UW Madison — and across the nation,” Melrod writes.

“There was such a strong movement among students,” he recalled — a feeling “that we could finally change the world.”

Demonstrating against the war in high school, he had encountered blue-collar workers who derided anti-war protesters as traitors. But in Madison, he met labor union members who joined in grocery story pickets in support of the farm workers, Melrod says.

“Those guys had the belief that the world could be changed,” he said. When students struck to protest the invasion of Cambodia and the killing of four students at Kent State University by National Guard troops, union groups in the community showed their support.

“That had a lot to do with me thinking, if I’m going to really continue on this path of trying to bring about real change for minorities, for Black people, for women, I’ve got to go and take my place where the power is — and the power lies with working people and in their unions,” Melrod said.

Those were conflict-ridden and sometimes violent years as students agitated against the war and the social and economic ills they saw around them and authorities responded by deploying the National Guard. Then the August 1970 bombing of the Army Math Research Center — in which a researcher was killed — cast a pall over the student movement at the university.

For Melrod, that was the precursor to his next chapter after UW. He moved to Milwaukee, took a series of factory jobs and wound up at the American Motors Corp. plant in Kenosha, where United Auto Workers Local 72 was legendary for its tough stance at the bargaining table and on behalf of its members. There he and a group of other young UAW members formed a militant caucus to confront imperious bosses.

As more Black and Hispanic men and women went to work at the auto plant, he once again saw the impact of racism, this time on the factory floor.

Some of it showed itself in notoriously racist management practices, such as a foreman who would harass Black workers. But it also surfaced closer to home. Melrod and other white leaders in their caucus took on a racist union steward and called a meeting of the union workers in their department.

“It turned into a session where people spoke out for the first time about how the union had to fight racism and how union representatives couldn’t be racist,” he said. “It was a really inspirational moment to show that on the most basic level, democracy works in a union, and it leads to transparency and militancy.”

The caucus published a newspaper, “Fighting Times,” from which the book gets its name. The paper called out bosses and named names, and got sued for defamation by one of the targets.

After a trial in which the judge directed a guilty verdict but the jury awarded no damages, the National Labor Relations Board found that the company had funded and directed the lawsuit. The NLRB issued a complaint that charged the company with an anti-union unfair labor practice and ordered AMC to pay the defendants, including Melrod, $283,000.

Melrod left Kenosha in the mid-1980s to go to law school and moved to the West Coast, where his practice has focused on refugee and asylum law. Now in his 70s, he says he wrote the book to help his sons understand what motivated his choices over the years as a union activist after he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer.

Melrod is heartened by the revival of union activism in recent years, particularly because of how it has engaged people across racial and ethnic lines.

“It’s really about dignity,” he said. “When I read about the Amazon and Starbucks workers, they’re not just fighting for a little more wages or some more break time. They’re really fighting for dignity — the same dignity that goes back to ‘Modern Times,’ Charlie Chaplin. About being chewed up in the cogs of industrial machinery.

“They want to be treated like human beings, and treated with respect.”