By Chelsea Risley

Southern Review of Books

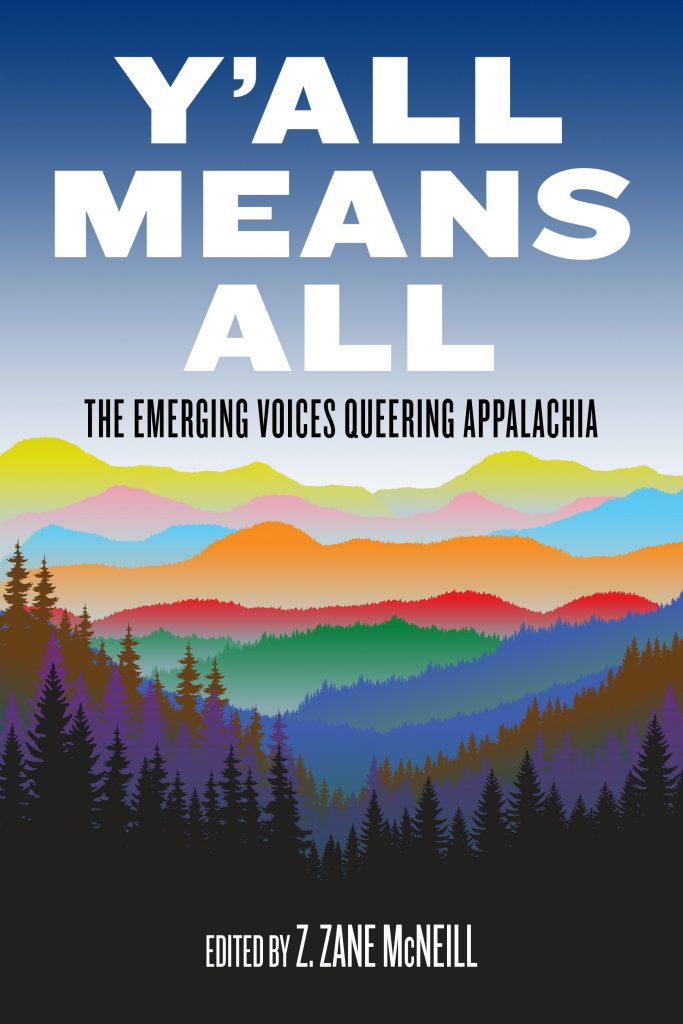

A thoughtful and accessible exploration of what it means to be queer in Appalachia, Y’all Means All: The Emerging Voices Queering Appalachia is a collection of essays that is both an exploration and a celebration of the region. As many who live in Appalachia and the South already know, these areas are misunderstood and misrepresented in so many ways. This collection challenges the assumptions of outsiders and highlights the voices of queer Appalachians who approach the discussion from a variety of backgrounds and disciplines.

This collection doesn’t necessarily feel focused on changing the minds of outsiders, though. It feels like it’s written for Appalachians, and I felt relieved and indeed hopeful as I read. The introduction states, “This collection is born out of optimism — we situate ourselves within an Appalachian history of resistance and envision an Appalachian queerness fueled by radical community-making, mutual aid, and solidarity in movements for intersecting justices.” I can’t help but be caught up in the optimism of the scholars and writers in this collection.

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with the editor of the collection, Z. Zane McNeill.

Z. Zane McNeill is an independent scholar-activist from West Virginia. He currently sits on the steering committee for the Appalachian Studies Association and has written on choreopolitics, socially engaged art, critical animal studies, and queer ecologies. They are co-editor of Queer and Trans Voices: Achieving Liberation Through Consistent Anti-Oppression.

How did you come to Appalachian Studies and activism? Was there a particular book or article you read that first made you feel seen and introduced you to this area of scholarship?

So, I’m from Morgantown, WV and spent most of my life wanting to get out of the region, actually. I went to college in Maryland and did a subsequent master’s in Budapest. After I left the region for school, I realized how people saw and judged me and my community. Right from orientation onwards, I faced a lot of stereotypes and microaggressions. A lot of them had to do with class and poverty. It made me feel really defensive and alienated.

During college, I also started identifying as queer and felt really uncomfortable and confused with the metronormative expectations of what a queer person and queer community looks like. In 2018, I was in Hungary and Queer Appalachia’s Electric Dirt had just come out. For the first time in my life, I felt seen and found a queer community that made sense to me.

Queer Appalachia framed queerness as leftist, as poor, as radical, as messy, and in a vocabulary like “dirt queer” that made sense to me. I felt really empowered and started up my own zine that I called Marx in the Mountains that explored queer and trans radical activisms and lives in the mountains. It was everything that I was told in college didn’t exist. I got to connect with all these great scholars and activists and queers through that project.

What inspired you to put this anthology together?

The community that cropped up around Queer Appalachia and Marx in the Mountains (mostly curated on Instagram) was really determined to challenge the stereotypes about our region and the erasure of our existence. And we were pissed off. Trump was in office. Pipelines were being built. Our waterways and our mountains were being extracted and polluted by outside capitalists. That fire and grit and community and idealism and dream making became this collection.

A lot of the contributors were just starting their PhDs and MAs at the start of this project. Now they’re graduating and pretty prolific and wonderfully disruptive. A lot of the connections made from this project became other book projects and special issues for journals and community projects and collaborative art projects. We went into this project wanting to archive queer Appalachian voices and imagine queer Appalachian futures and now we’re creating new queer Appalachian scholarship, pathways, and speculative futures together.

What was the publishing process like? What has been the best part?

Very, very messy in the most queer way possible. Right before the manuscript was finalized, the Washington Post article came out, alleging that Queer Appalachia was run by grifters who had defrauded folks who had donated to their direct action efforts and fucked over the BBIPOC community. Queer Appalachia knew it was coming, I think, but they didn’t warn me or the other folks who had been working with them though, so we got the blowback.

Mamone, the main person running the QA platform at that time, and their partner, Chelsea, had a few chapters in the book, and as a collective, we had to decide what to do about the article and QA’s involvement. Some folks actually pulled their chapter from the collection because they were afraid that they would be connected with QA. We couldn’t verify some of the facts that were in QA’s chapters, so we ended up pulling them.

It was a really difficult decision and really made us question the project. Many of us, like me, had found our queerness and this community through QA. We had been really dedicated to their direct action, harm reduction, and mutual aid approach to queerness and that really framed our work. After the fall of QA, though, there was a tendency to write off all the work that they had done and the community that they had curated. My friend Jessica Cory and I edited a special issue of the Journal of Appalachian Studies that has a chapter in it by one of my favorite humans, Maxwell Cloe, on the incident and what we can learn from it.

The best part of the publishing process, though, was for sure the community we made together. In the end, this collection was published and I’m really proud of it. It is funny though, because a lot of the content is from 2018 and so much of the world has changed. I’m optimistic about where we can go together though and what queer organizing and worldmaking in the future can look like.

Did anything surprise you in the publishing process or as you edited the chapters?

It is really, really hard to get a project from the idea phase to an actual physical thing that exists in the world. A lot of editing is like herding cats — people commit, priorities change, and they drop out. We probably had three or four waves of different folks coming into the project after other folks dropped. Some of the contributors had been part of the project since its inception, others I asked to join a few weeks before the manuscript was due.

We were on a panel about this collection at the last Appalachian Studies Association conference, and someone asked each contributor how they got involved in and found this project. It was funny because I realized that, for most of the folks, I found their work, thought they were super cool, and begged them to be part of this book. I am so happy and humbled that this collection has these contributors. Each and every one of them are amazing, radical, really awesome people.

This collection represents such a wide variety of backgrounds and approaches and focuses. What have you learned from being a part of this community?

We were really dedicated to making the collection as accessible as possible. We all sit at multiple disciplines and have super entangled identities — many of us identify as a mix of scholars, activists, artists, writers, makers, you name it. Each contributor, whether a direct-action activist or a queer community member or a professor or a journalist, is in conversation with one another and has an equal amount to learn from one another. We’re also in conversation with those whose work we cite in the collection. This book represents how multifaced and diverse Appalachia is, and how queer Appalachia life and culture and being is. I’m so proud to touch the surface of it. We’ve been here forever doing work and loving and living, and there’s this idea that this is all new. What is new is that we are fighting for platforms to record our voices and are creating our own ways of archiving our lives.

What are your hopes for what this book will do in the world?

In addition to the community building work I’ve talked about, I also wanted to create a collection that I really wish had existed when I was in high school. I want queer folk to see that there are tons of really cool people just like them existing and thriving and fighting. I want them to know that they are certainly not alone — that there is a strong history of queer folks living in Appalachia and so much space and potential support for them to grow in this space in the future.

I also hope that folks outside the region — queer city people who think that growing up gay in Appalachia is always just horrible; liberals who think Appalachia is really just Trumpalachia; and conservatives who buy J.D. Vance’s reading of the mountains — really have their assumptions and stereotypes of what Appalachia and what queer Appalachia challenged and come out with a more nuanced understanding of our lives.

At the SRB, we often ask what you think people get wrong about your corner of the South, but I think Y’all Means All offers a lot of in-depth answers to that question. Instead, could you talk about what you love most about the South?

When I’m outside the region, I feel like I always have to translate my transness and queerness to others. I have to temper it down or perform a certain way or codeswitch to safely exist in cis spaces, and to be read and embraced as trans in queer spaces. When I come back home, I feel so much less exhausted and hyperattentive because I know that I am enough and don’t have to present a certain way or talk and sound a certain way to be seen. I feel more at home in my queerness in Appalachia than when I am outside of it.

Is there anything you don’t get asked about in interviews but would like to talk about?

This isn’t exactly a question, but since I’ve been given some space, I’d love to encourage folks to check out one of my favorite radical bookstores in Appalachia, Firestorm Books, in Asheville. They have supported all of my projects — Queer and Trans Voices: Achieving Liberation Through Consistent Anti-Oppression (Sanctuary Publishers), Vegan Entanglements: Dismantling Racial and Carceral Capitalism (Lantern Publishing), and Y’all. They are moving into a new space and are asking for donations from the community. They do amazing work for the community and y’all should totally support their work. If you can donate, you can do so here.