By Erin A. Cech

College & Research Libraries

July 2022

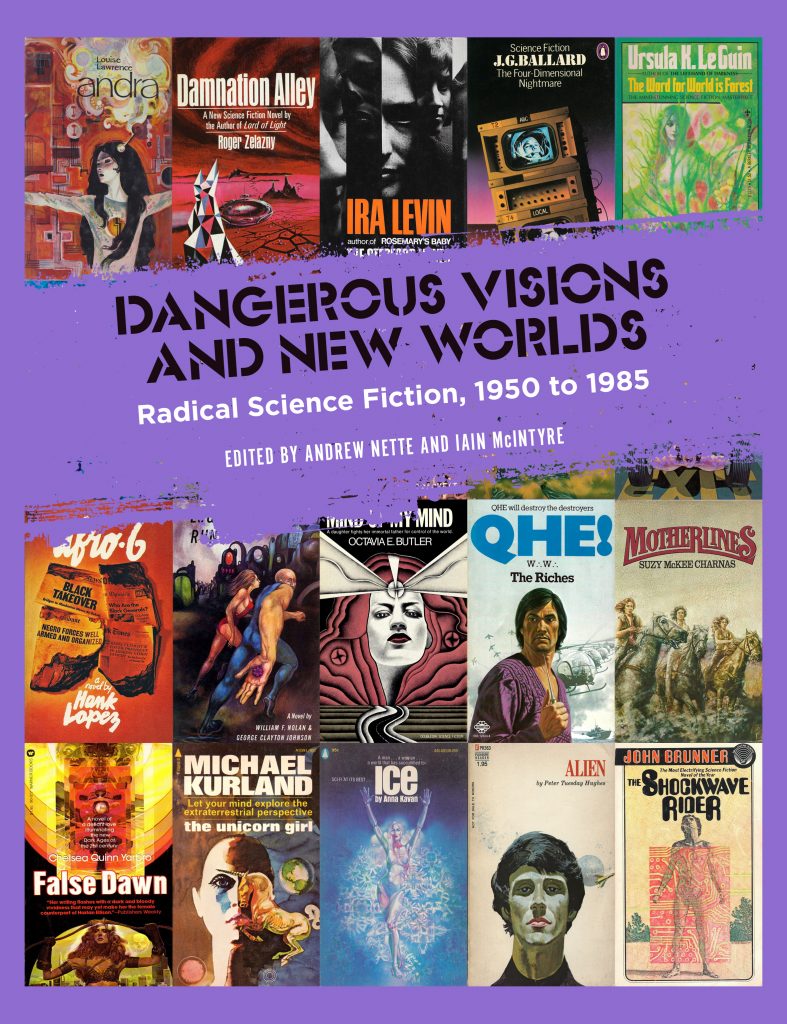

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985. Andrew Nette and

Iain McIntyre, eds. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2021. 216p. Paper, $24.60 (ISBN: 978-1629638836).

This essay collection on mid-20th century American and British science fiction literature is next in a series of overviews of “outsider” print fiction from PM Press that includes Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980 (2017) and Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 (2019). This review of science fiction features two groundbreaking New Wave science fiction publications in the book’s title: the magazine edited by Michael Moorcock, New Worlds, and Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions short story collections. The era covered by editors and authors Andrew Nette and Iain McIntrye primarily covers what they call the “long sixties,” but also encompasses novels and writers that address “radical” themes such as sexual politics, environmentalism, and social revolution outside that time period. Nette and Mcintyre include writers considered the stars of this era—Philip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin, James Tiptree, Jr., Robert A. Heinlein—but the strength of this collection is its inclusion of writers less well known to science fiction scholarship and fandoms: the Brothers Strugatksy, Judith Merril, Louise Lawrence, Larry Townsend. Other writers included are connected to others in the networks of science fiction history. Luminaries like Octavia E. Butler had an early short story purchased by Harlan Ellison for an as-yet unpublished Dangerous Visions volume.

The book’s chapters also offer insight into the changing publishing industry, and to economic and political systems that determined whose stories got published. The authors address how science fiction sought not only legitimization as literature but also transformed into a commercialized multimedia industry. Many of the science fiction writers included in this collection did not have the privilege to write literary fiction and wrote for publishers who wanted work that could easily sell. The growth of the paperback novel medium was central to the history of popular culture. Some of these science fiction writers wrote using pseudonyms, not necessarily to cover their gender, but also to conceal their real-life identities or workplaces that might look askance at association with science fiction and its fan cultures.

However, this did not stop science fiction and pulp writers from using their work as a vehicle

for other ambitions: aesthetic, experimental, and political.

The editorial approach is archival, with choices guided more by contributor interest than editorial design. This allows for some conspicuous and disappointing omissions. For example, the chapter on Samuel Delany covers Heavenly Breakfast, a memoir about living in a New York City commune in 1967–1968 that provides an excellent thesis about how these experiences are reflected in his science fiction. That said, there is little here that considers the breadth of Delany’s work in the decades covered by this book. The omission of a fuller discussion of writers gestured to, such as Joanna Russ, or themes like Buddhism and science fiction, is disappointing. Connecting threads with more contemporary science fiction writers and with genres like cyberpunk, Afrofuturism, and queer science fiction would also make the work a stronger contribution for general collections. The reader hoped for an account of Theodore Sturgeon’s groundbreaking 1953 short story about aliens and homophobia, “The World Well Lost,” and Sturgeon’s subsequent blacklisting by some science fiction publishers.

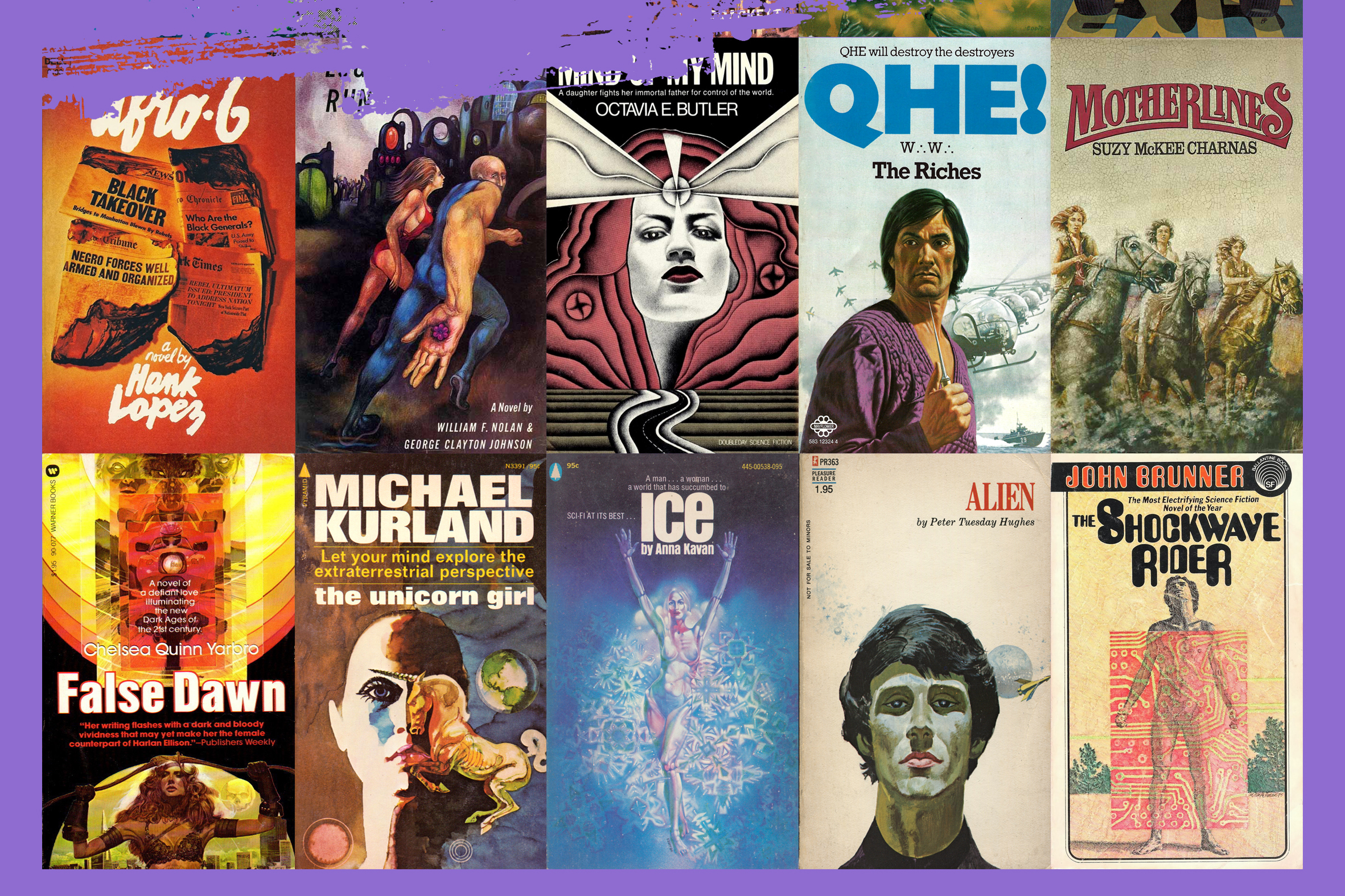

However, in keeping with the archival approach, the book offers encounters both unique and unexpected—material that one did not expect to find. Nearly every chapter/essay includes an array of color book covers for books whose writers are not necessarily discussed at length in the text. These images may lead researchers down new and fascinating rabbit holes.

Following their earlier work, Nette and McIntyre also position the changes in science fiction

content in relation to the changes in the publishing industry. The chapter on a publisher of

science fiction/pornographic paperbacks, “Speculative Fuckbooks: The Brief Life of Essex

House, 1968–1969,” by librarian Rebecca Baumann, is a particularly valuable contribution.

Dangerous Visions and New Worlds provides far more than the introductory summaries one

might find in reference sources like Wikipedia. Careful attention is paid to lesser-known writers,

such as Jean Marie Stine and Alice Louise Ramirez, and its inclusion of them as science fiction

pioneers is valuable, necessary work. This work is also more suited for general reading rather

than scholarly research (bibliographic references or footnotes not included), although the analy-

sis provided is certainly of that caliber.—Ann Matsuuchi, LaGuardia Community College, CUNY

Erin A. Cech. The Trouble with Passion: How Searching for Fulfillment at Work Fosters Inequal-

ity. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2021. 344p. Paper, $29.95 (ISBN: 978-

0520303232).