By Mitchell K. Jones

Midwestern Marx

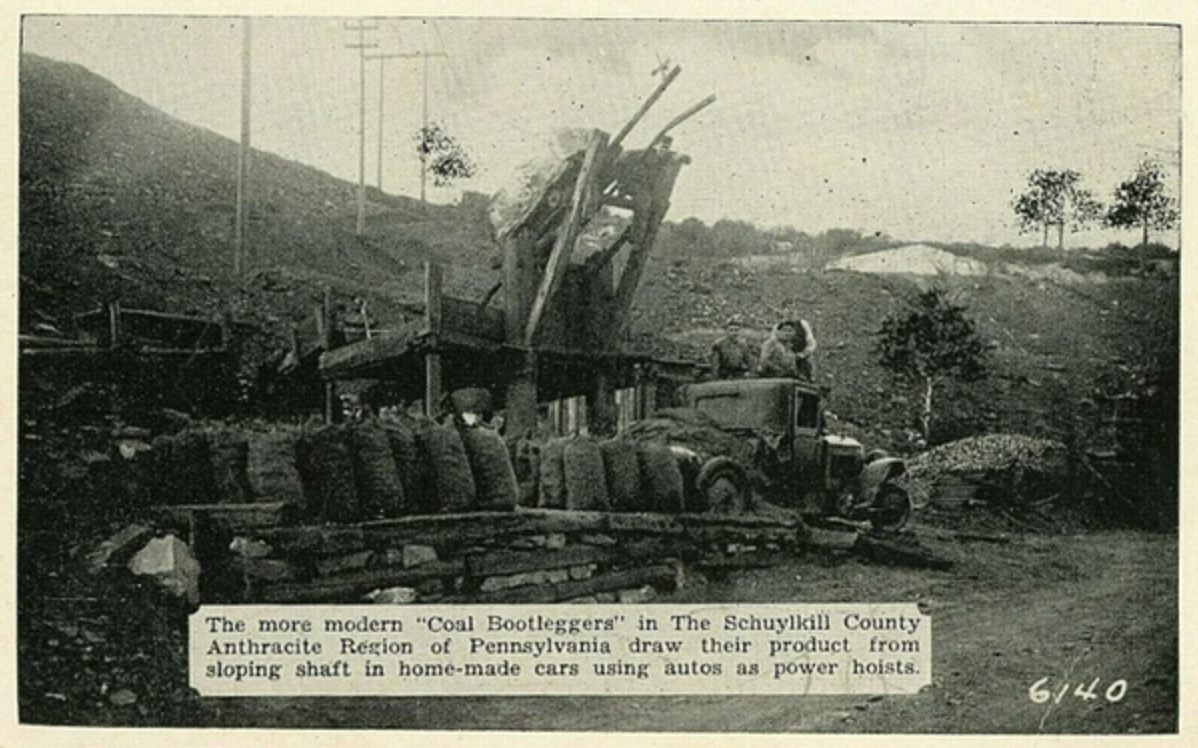

Modern “Coal Bootleggers” in Schuylkill County”. Postcard circa 1945.

A bootleg mine shaft near Ashland, Pennsylvania.[1]

A headline in the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania newspaper the Daily Item reads, “Man Charged with Stealing 3,000 Tons of Coal.”[2] According to the article, “The surveyor told police when he conducted the inspection, he used a known survey point that dated back to the 17 and 1800s, according to court documents. The surveyor told police Four Vein Coal Company was mining coal off of Reading Anthracite property, police said.”[3] Mitch Troutman’s Bootleg Coal Rebellion The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry started with curiosity regarding contemporary examples of coal bootlegging such as this one. This curiosity led Troutman to discover the long ranging, often militant history of the practice of coal bootlegging in the anthracite coal region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. The result was Bootleg Coal Rebellion, a regional history brimming with passion and pride for the radical legacy in Troutman’s home state. Troutman traces the region’s history of contradiction between the workers’ desire for a decent way of living and the coal bosses desire for greater and greater profits from the Molly Maguires of the 1870s to contemporary reports of coal bootlegging in an attempt to answer the question, “How did we start treating coal company property like it belonged to us?”[4] Troutman’s passion for local history comes through in his writing. Discovering revolutionary elements in his own area’s past inspired Troutman to look deeper into the radical history of the region. The researcher’s quest is invigorating. The “Eureka!” or “Aha!” moment when you discover a connection that nobody else has identified before is ethereal and sublime. Researchers are addicts, chasing that first big high. This spirit is palpable in Troutman’s writing, resulting in a compelling narrative and a stimulating read.

Troutman’s approach is historical materialist. He starts by discussing the land, the differences between bituminous and anthracite coal and the differences, both cultural and geographical, between the bituminous regions of Northern Appalachia and the anthracite region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He then breaks radical and bootlegging activity in the anthracite region down town by town.

Bootlegging was the practice of building small “coal holes” near mining company property that allowed unemployed miners access to mines that the company had closed. The practice is as old as the collieries themselves, but coal bootlegging hit its peak during the Great Depression of the 1930s. “Coal holes” were dangerous and whole families, including children, often worked them. Truckers got the illegal coal to markets. Breakers were black market businessmen that set up bootleg coal operations. The consumers were often shop owners that were aware the coal was bootlegged, but were happy to buy the product at a price lower than the official collieries. The coal monopolies’ and the states’ attempts to stop bootlegging led to an alliance between working class miners and truckers, and petit bourgeois breakers and even retail merchants, despite their reliance on the Reading Railroad monopoly who had an interest in preventing bootlegging since they leased land to the colliery companies. The interdependent web of complicity held this illegal economy together.

Mutual aid and democracy were also key values that held bootlegging communities together. The rank and file workers fought with both the official United Mine Workers union leadership and the company bosses over the issue of “equalization.” Trautmann describes equalization as, “the spreading of available working hours among all employees, so as not to lay anyone off.”[5] Clearly workers’ communitarian faith in mutual aid trumped selfish desires. Bootlegging, despite its dangers, was a communal activity. Neighbors agreed to be silent around Iron and Coal Police while whole families of bootleggers mined “coal holes” for use and sale in the community. Troutman describes the spirit of anthracite region families in hard times: “A family with more eggs than it could eat might trade with a neighbor for tree fruit, for a visit from a neighborhood healer, or for harvest-time crops that could be preserved or pickled. Additionally, many had the crafting skills necessary to create anything from baskets to clothing.”[6] Strikes were often called in defiance of the UMW. The United Anthracite Miners of Pennsylvania (UAMP) formed in defiance of the UMW’s anti-equalization policies and struck on their own. Unfortunately, the UAMP’s leader Tom Maloney was murdered on Good Friday 1836, vanquishing the more radical wing of the miners’ movement. The companies’ and moderate unions’ attempts backfired, resulting in a coal bootlegging boom. The illegality of the industry solidified communitarian bonds. The complex networks of families, miners, truckers, breakers and consumers softened racial and gender boundaries as well.

Troutman argues coal bootlegging was both a means of subsistence during hard times and a radical rebellion against the coal monopolies. Miners bootlegged out of necessity to survive the severe times, but the practice also made it clear to the coal bosses that without the workers there would be no coal. Most interesting is Troutman’s description of Communist Party (CPUSA) run Unemployment Councils in the anthracite region. CPUSA assigned organizer Steve Nelson to move to Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania to set up Unemployment Councils in the anthracite region. Nelson explained how communists had to be sensitive to the culture and people of the region, “[T]he old sectarian approach, with its emphasis on abstract theory and rhetoric, constant adulation of the Soviet Union, and a hostility toward all radicals outside the Party, would not work. We concentrated instead on issues of vital concern to working people.”[7] Troutman describes the Shamokin Unemployed Council as a case study:

They had subgroups for homeowners, youth, and women. They petitioned and marched for moratoriums on evictions, sherif’s sales, utility shut offs, and property tax. If someone—involved in the committee or not—was in trouble, the council would show up and physically stop evictions and utility shut offs, negotiate with utility companies, or, when all else failed, reconnect the utilities illegally. They often succeeded at all of it.[8]

Anti-communist and communist miners worked side by side. Often their lives literally depended on each other. They made jokes about their differences, and there were certainly tensions, especially between Irish Catholics and atheist communists for example, but at the end of the day, they were ready to risk their lives to save their fellow miners.

Troutman’s Bootleg Coal Rebellion is a compelling story and a lesson for socialists and organizers today. Through his focus on the rebellious, democratic and communitarian elements of the coal bootlegging movement and the ways that radicals adapted their message to appeal to these pre-extant sentiments in the anthracite region, Troutman gives us hope that those same rebellious, democratic and communitarian spirits, ever present in the proletariat, can still be nurtured into revolutionary potential today. More importantly, Troutman’s book turns our attention to the Unemployed Councils of the 1930s and the work of communist Steve Nelson in the anthracite region. Nelson and the Unemployed Councils’ example is a blueprint for organizing and mutual aid in the future as the volatile neoliberal economy heads into another period of crisis and workers are already once again turning to desperate measures to survive.

[1] By Jasontromm, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=29221915

[2] Francis Scarcella, “Man Charged with Stealing 3,000 Tons of Coal,” Sunbury Daily

Item, September 24, 2016

[3] Scarcella, “Man Charged with Stealing 3,000 Tons of Coal.”

[4] Mitch Trauttman, The Bootleg Coal RebellionL The Pennsylvania Miners Who Seized an Industry 1925–1942, (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2022), 5.

[5] Troutman, The Bootleg Coal Rebellion, 48

[6] Ibid., 45.

[7] Ibid., 130.

[8] Ibid., 131.

Author

Mitchell K. Jones is a historian and activist from Rochester, NY. He has a bachelor’s degree in anthropology and a master’s degree in history from the College at Brockport, State University of New York. He has written on utopian socialism in the antebellum United States. His research interests include early America, communal societies, antebellum reform movements, religious sects, working class institutions, labor history, abolitionism and the American Civil War. His master’s thesis, entitled “Hunting for Harmony: The Skaneateles Community and Communitism in Upstate New York: 1825-1853” examines the radical abolitionist John Anderson Collins and his utopian project in Upstate New York. Jones is a member of the Party for Socialism and Liberation.