by Robert Knox

Fifth Estate

# 411, Spring, 2022

a review of

The Blast by Joseph Matthews. PM Press, 2022

The Blast, a new novel by Joseph Matthews, takes place in San Francisco in 1916, just as the United States edges its way into the general European slaughter known as World War I.

We learn that three years before the current moment, labor radicals and anarchists of various denominations agitated mightily for workers’ rights and union recognition in that thriving waterfront shipping town, but failed to make lasting progress.

Now, a new effort, led by militant socialist Tom Mooney, is haltingly under way to organize the city’s United Railroad workers. You might describe the arc of this book as what led up to the eventual railroading of Mooney for an act he did not commit. Set in the months leading up to the city’s Preparedness Day Parade, an effort by the city’s big businesses and captive mayor to drum up enthusiasm for US entry into the war, the book leads up to a bombing for which labor militants were framed.

Readers unfamiliar with Mooney’s role in labor’s dark days will not learn of his significance from reading The Blast, though if they read the Author’s Note at the book’s conclusion they will be better informed. I am tempted to urge prospective readers to consult the author’s note before beginning the novel, not only for its useful, obviously well researched discussion of the time and place in which the story is set, but for some understanding of why the events in the book’s nearly 400 pages matter.

The novel has two central characters. Blue, a still young San Francisco native who left town after the collapse of those earlier union efforts, is a onetime prize fighter “broadly anarchist” in his views, whose significant usefulness for political agitation is his expertise in laying explosives. He appears to have embraced the life of a drifter, going back into the ring when short of ready cash, and only returning to his hometown because of reports that the action on the waterfront has started up again.

Blue’s unfocused bumming-about the-town existence deserves attention only when, a hundred pages in, we learn that he had spent time in England conspiring with “disruptive” suffragists to blow up power stations. This episode, intriguingly told, builds anticipation that a young man of Irish and Italian ancestry, with some obvious talents, will find a way to put them to use in San Francisco.

Blue’s history as a youthful prizefighter opens interesting possibilities for storytelling, though again, the compelling piece of the storyline takes place in the past. The main event transpired when a talented local Black fighter, a onetime personal friend, is matched against him in one of those Joe Louis versus Max Schmeling race-war mashups.

Now, the Black fighter turns up in a different role—he’s a scab—with a meaningful bone to pick with Blue. It’s a promising conflict, but we long for a culminating big scene between them in vain.

While we wait for the book’s diffuse cast of radicals of varying ethnicities to commit to some form of plot momentum, the novel turns its attention to the second central character. Kate Jameson, an intelligent and sympathetic widow of a certain age, routinely demeaned by male authority figures, is somehow plucked from a Boston law office by US Secretary of State Robert Fanning to gather information on whether San Francisco powerbrokers are willing to back America’s entry into the war. The city’s seaport, we’re told, is crucially important to the war effort.

A daughter of Boston’s Southie working class neighborhood who married the son of a wealthy family, Kate’s main qualification appears to be that she once lived in that city. But for most of the novel her stay in Frisco proves even less productive than Blue’s.

The pretentious and frivolous society entertainments in which Kate tries to meet cliched influential rich people and sound them out on their war-appetite, lack even the pleasurable scrappiness of an episode in which Blue’s anarchist acquaintances from different regions of Italy argue over whether a dish of pasta and clams can be served with cheese or not.

Kate’s story gains traction when the novel focuses on her real intent in accepting the West Coast job: hunting for her disappeared daughter. It’s this search that will turn out to harbor the book’s true emotional impact, its claw on the reader’s heart.

Before the novel’s climax (spoiler alert: potential readers may wish to stop here), the blast that eventually does go off, Kate discovers the circumstances behind her husband’s suicide, caused we learn, by what he was forced to do as an Army doctor in the Philippines when Imperial America was suppressing a native insurrection by the kind of vile means later practiced in Vietnam, Iraq, and Guantanamo.

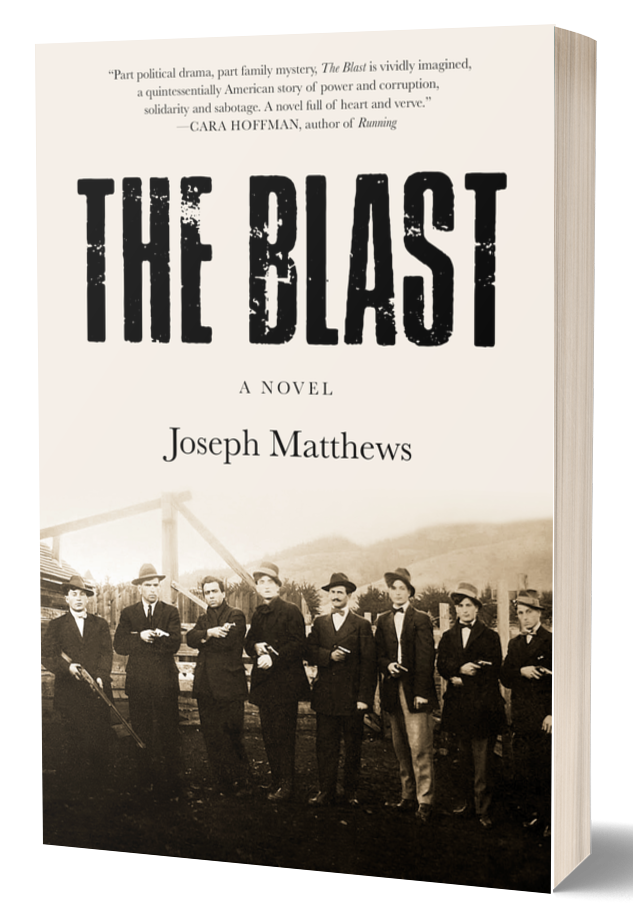

It’s tempting to return to my initial assessment and suggest that readers seeking an insight into West Coast political movements in the early nineteen-teens benefit from reading the solid and informative author’s note before turning to page one. But don’t get misled by the book’s arresting and truly marvelous period cover photo depicting eight men in dark coats and hats, all displaying firearms. We learn from the small print on the book’s back cover that the photo depicts “a portion of the Gruppo Anarchico Volonta” in San Francisco.

Unlike Chekov’s famous adage, “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one, it should be fired. Otherwise, don’t put it there,” these firearms don’t go off.

Robert Knox is the author of Suosso’s Lane, a novel about the origins of the Sacco and Vanzetti case. His new book of linked short stories, House Stories, set in counter-culture 1970, is available from Adelaide Books and Amazon.