By Michael Beykirch

Fifth Estate

# 410, Fall, 2021

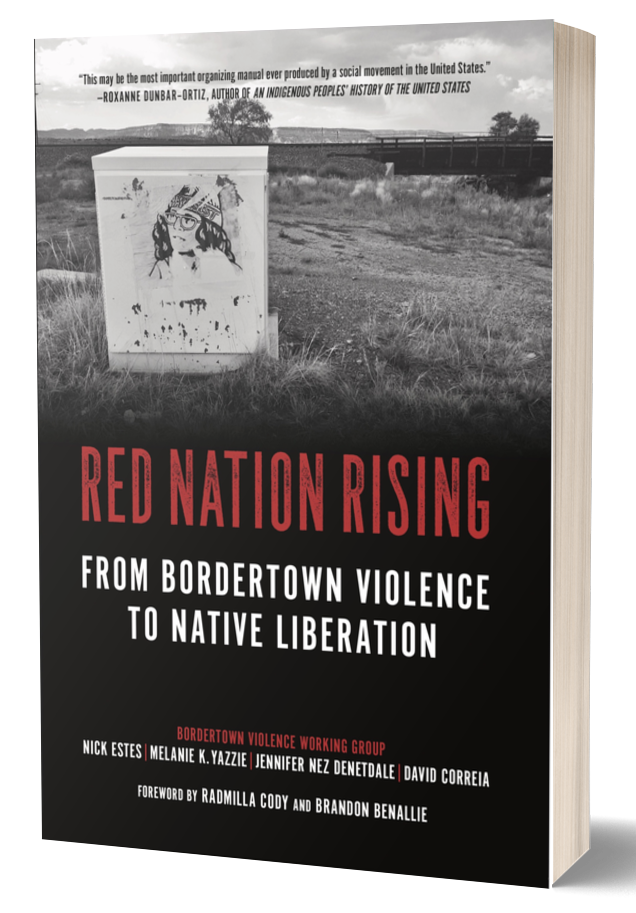

a review of

Red Nation Rising: From Bordertown Violence to Native Liberation by Nick Estes, Melanie K. Yazzie, Jennifer Nez Denetdale, and David Correia. PM Press 2021

“I can’t fucking breathe,” Zachary Bearheels (Rosebud Sioux) said before he died in Omaha, Nebraska, in 2017, where cops tased, then mounted him on the pavement, and punched his head 13 times. Murdered. In a bordertown.

Relating this horrific crime, the authors of Red Nation Rising define bordertown as a place where the genocidal violence of European settlers and their ideological heirs meet Native resistance. They distinguish this Native concept from the two-worded state concept of border towns, towns along international lines such as those dotting the boundary between Mexico and the United States.

Historically, European settlers savagely invaded North America—or Turtle Island, as the authors and many of their kindred activists call the continent-and then bludgeoned their way across Native homelands. As a result, Native adults and children first bore and resisted this violence along these expanding frontiers. Yet for reasons the authors detail, settler violence never ceased, and Native people have never stopped resisting it. Thus, we find bordertowns everywhere. Even in Omaha today.

The recent news from Canada told more of the workings of these bordertowns. Researchers in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia discovered over 1,000 unmarked graves of Native children at former boarding schools. Perhaps among the 500 such schools across the continent that the Canadian and US governments funded and that, in many cases, Christian churches ran, 10,000 Native children died resulting from disease, accidents, and suicide. They often lived in squalor, hundreds of miles from their homes and suffered beatings, sexual abuse, and tortuous practices meant to strip away their heritage.

Where the bordertown failed to kill all Native people, its Indian boarding schools turned to killing their identity in order to assimilate their children into the dominant settler culture.

Yet Native people resisted. In Pennsylvania, in 1897, for example, two girls, Elizabeth Flanders and Fannie Eagle-horn, set fires in an attempt to burn down the girls’ dormitory. They fought to go home, but ended up in prison.

In 1895, as Red Nation Rising points out, the United States charged Hopi leaders with sedition and imprisoned them for refusing to send their children to boarding schools.

If the news from Canada told part of a story, one that shocked the world, Red Nation Rising unapologetically not only indicts the bordertown and describes its every facet, but also calls for its destruction so that a kinship to people, to other species, and to the Earth may arise: “Our goal is not to understand the bordertown but…to map its weaknesses so we can burn it to the ground.”

To map its weaknesses, the authors hone in on, among other facets of the bordertown, settler law, class, police, capitalism, hate crimes, gender, and gender violence. A whole section of the book discusses Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirit people (#MMIWG2S).

It begins with a stark list of 27 of their names, including the names of murdered or missing Native trans women. The poignant list succeeds where cold statistics fail. Nevertheless, when the book cites the thousands and thousands of Native girls and women that disproportionately go missing, it concedes that even those statistics underestimate the real extent of such gender violence. Often the missing go unreported, and some such as trans women go uncounted because they’re not considered female.

The authors lambaste the culture industry, but they then turn around and temper the steel of their arguments with examples of Native music and humor. The group, A Tribe Called Red, released their lyrically and musically potent song “Burn Your Village to the Ground” on Thanksgiving Day 2014. Evoking settler land theft and decadence, the song sardonically ends with a call to scalp Pilgrims and to burn their villages to the ground. (The listener might recall that white settlers were the ones who collected scalp bounties.)

The authors quote examples of Vine Deloria Jr.’s (Standing Rock Sioux) humor: “Indians have been cursed above all other people. They have anthropologists.” Beyond explaining how anthropologists have dehumanized Native people as objects of their studies, the authors wryly continue with their own list of settler curses: pawn brokers, Christian missionaries, Indian agents, and bureaucrats. “And other parasites who infest Indian Country.”

Working collectively, the authors also turn to other comrades and elders. The works of Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna Pueblo), Kim Tallbear (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate), Dian Million (Athabascan), Joanne Barker (Lenape), Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (Dakota) all excoriate the bordertown. And the authors pithily quote Jodi Byrd (Chickasaw): “The story of the new world is horror…The story of America is crime.”

The authors evoke the recent insurgencies in Oak Flat, Mauna Kea, and Standing Rock, where people have fought to protect sacred Native lands and resources. They optimistically name this new wave of uprisings an intifada, one that scares the settlers; almost 100 law enforcement agencies deployed at Standing Rock to defend their lawless border-towns.

A short book—133 pages followed by notes and an index—Red Nation Rising demands, in the name of humanity, the liberation of Turtle Island and of the world, “which would effectively mean the demise of settler states and the restoration of Native sovereignty premised on values of caretaking, democracy, equality, and autonomy.” And, it invites its readers to join that struggle for liberation.

About Red Nation Rising the historian and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz wrote that it “may be the most important organizing manual ever produced by a social movement in the United States.”

Certain books and people have helped us understand and struggle against injustice. A few have even profoundly marked our lives. For a lot of readers, this book, one imagines, will be one of those few.

Michael Beykirch teaches languages other than English at a community college in New York State. He lives, works, and rides his bicycle on stolen Native land.