Sara Nelson, the head of the largest flight attendants’ union, leads her members through turbulent times and mounts a major organizing drive at Delta.

By Jennifer Gonnerman

The New Yorker

May 23rd, 2022

t the beginning of 1996, Sara Nelson was twenty-two years old, living in St. Louis, and working as a waitress at a California Pizza Kitchen. A recent college graduate, she had a job lined up for the fall as a high-school English teacher, and in the meantime she was juggling three part-time gigs in addition to her restaurant job. Then, one day in February, she got a call from Chloe Caviness, her best friend from college. “Guess where I am,” Caviness said. “The beach in Miami!” After graduating, Caviness had started working as a flight attendant for United Airlines. Now, on the phone, she went on and on about the job’s perks, which included layovers in warm locales, and Nelson wondered if she ought to apply.

She recalled thinking, “I’m freezing my ass off, working four jobs, and life is hell. O.K., all right, I’ll check this out.” As it happened, United was holding a recruitment event the next day in Chicago, a five-hour drive from St. Louis. Nelson gave away her restaurant shifts, then got in her car and began heading north. She slid a mixtape into the deck—she loved Barbra Streisand—and sang loudly as she drove. Later, when she arrived at the event, “there were applicants in line crying,” she said. “They would start to talk about how much they wanted this job, and they would get emotional.” United called the event an open house, but there were so many people that Nelson referred to it as a “cattle call.”

She made it to the second round of interviews, at which point the airline administered a test to make sure that she could speak a second language—a desired qualification for flight attendants at the time. Nelson, who had taken German in college, was “barely conversational,” but somehow she passed, and, after enduring a physical and making it through six weeks of training, she was hired.

United assigned her to its base in Boston, and she moved to the city that fall, living in an apartment with seven other rookie flight attendants. She spent the first few months working on call, filling in whenever the airline was short a flight attendant, but soon she had enough seniority to get a monthly schedule, and eventually she was able to work the most desirable trips, like the non-stop flights to San Diego. She’d pack her swimsuit, depart at 8:30 a.m., and land before noon Pacific time. “We’d have all day where we could go to the beach,” she recalled. “If you went on a Tuesday or a Wednesday, the only other people on the beach were likely airline employees.”

After working at a restaurant, Nelson appreciated the autonomy that came with being a flight attendant. “We don’t have managers watching us,” she said. “When we get up there, we control the workspace.” Once the plane took off, she and her co-workers would “read the room,” and, if the passengers seemed to be in a “festive mood,” the flight attendants might hold a trivia contest, awarding a bottle of champagne to the winner. Even on her days off, Nelson spent time in the sky; she could fly for free, and on one of her first vacations she flew to Honolulu. She got used to the life style, and whenever she thought about the possibility of one day having to work a different job she panicked. “I was just horrified by the idea of being an earthling,” she said.

United employed some twenty-five thousand flight attendants at the time, but its base in Boston was relatively small—only about three hundred flight attendants. It was also a union shop: United flight attendants are members of the Association of Flight Attendants. (The A.F.A., founded in 1945 by a group of United stewardesses, is the largest flight attendants’ union, representing workers at eighteen airlines.) At United, nearly all the flight attendants wore their union pins, and at the Boston base Nelson soon discovered that there was a “group of very, very senior flight attendants who were, I would say, quite militant.” In 1985, United pilots had gone on strike, and the flight attendants had struck in solidarity. More than a decade later, some flight attendants still carried around a “scab list.” Nelson recalled hearing stories about the punishments doled out to the workers who had crossed the picket line, “like somebody is doing a trip to Des Moines, and they find out, Oh, no, their bag is in Hong Kong.”

Nelson’s knowledge of unions was minimal. “I didn’t really know anything about labor at the time,” she said. But her first few weeks on the job taught her about the benefits of union membership. When she arrived in Boston, the leaders of the local union council were some of the first people she met, taking her and the other new hires on a trolley tour of the city. Not long after, when one of Nelson’s first paychecks was late to arrive, a co-worker offered to loan her eight hundred dollars, and then advised her to call the union for assistance. The union helped her get paid, and it also helped alleviate the sense of alienation that she felt as an employee of a huge corporation. (“It was the first time in my life that I knew what it meant to be a number,” she said.) “The idea that you would have each other’s backs, that you would be welcoming—it felt right,” she told me. “I identified with that right away.” Within a few months, she was volunteering with her local union council.

Today, at age forty-nine, Nelson is the international president of the A.F.A., which represents fifty thousand flight attendants in the U.S., or about half the flight attendants in the industry. She frequently testifies at congressional hearings, where at times she is the lone woman seated alongside the C.E.O.s of the nation’s largest airlines. During the government shutdown that began in late 2018, when hundreds of thousands of federal employees—including T.S.A. workers—went unpaid for weeks, she gave a speech calling for a general strike. (The speech got national attention, and later, when a CBS interviewer suggested that Nelson was threatening to “shut down the whole economy,” she calmly responded, “Yes.”) Nelson was credited with helping to end the shutdown, prompting the Times to describe her as “America’s Most Powerful Flight Attendant.”

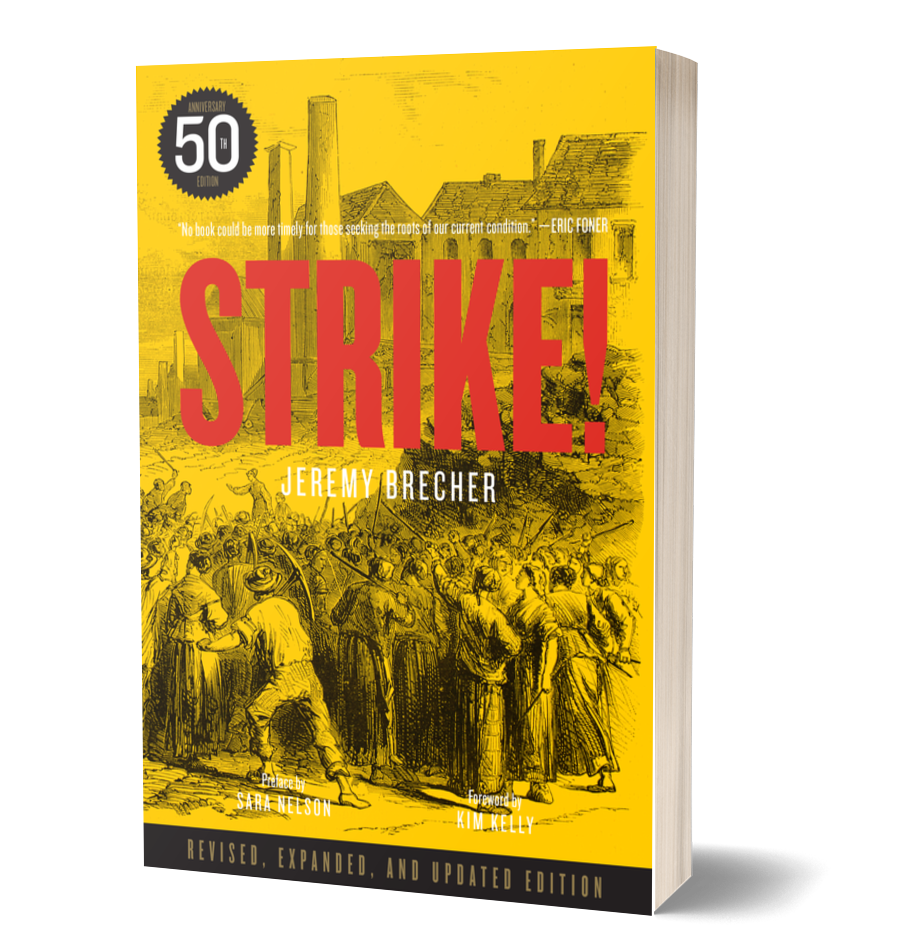

Producers at CNN, MSNBC, CNBC, and Fox Business often invite her on air. She lives in a town house in Maryland with her husband and their twelve-year-old son, and during the pandemic a spare room on their second floor has doubled as a television studio. (When her son comes home from school and finds his mother staring at a screen, he whispers, “Are you on TV?”) On air, she comes across as incisive and unflappable, and, like any flight attendant, she is well coiffed, her shoulder-length blond hair blown dry. She usually sits in front of bookshelves lined with a few trinkets, including a miniature Bernie Sanders doll, and with books about organized labor, such as “Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America”—Elliott J. Gorn’s biography of the legendary union organizer—and a fiftieth-anniversary edition of “Strike!,” by Jeremy Brecher, for which Nelson wrote the preface.