by Guillaume Tremblay-Boily

Jacobin

After participating in 1960s progressive movements, Jon Melrod took his activism to the factory floor, becoming a militant rank-and-file autoworker. Radicals like him made serious contributions to labor struggle at a time when unions were under attack.

In the ’60s and ’70s, thousands of student radicals across North America and Western Europe decided to become manual workers to get rooted in the working class and participate in its struggles. Jon Melrod was one of them.

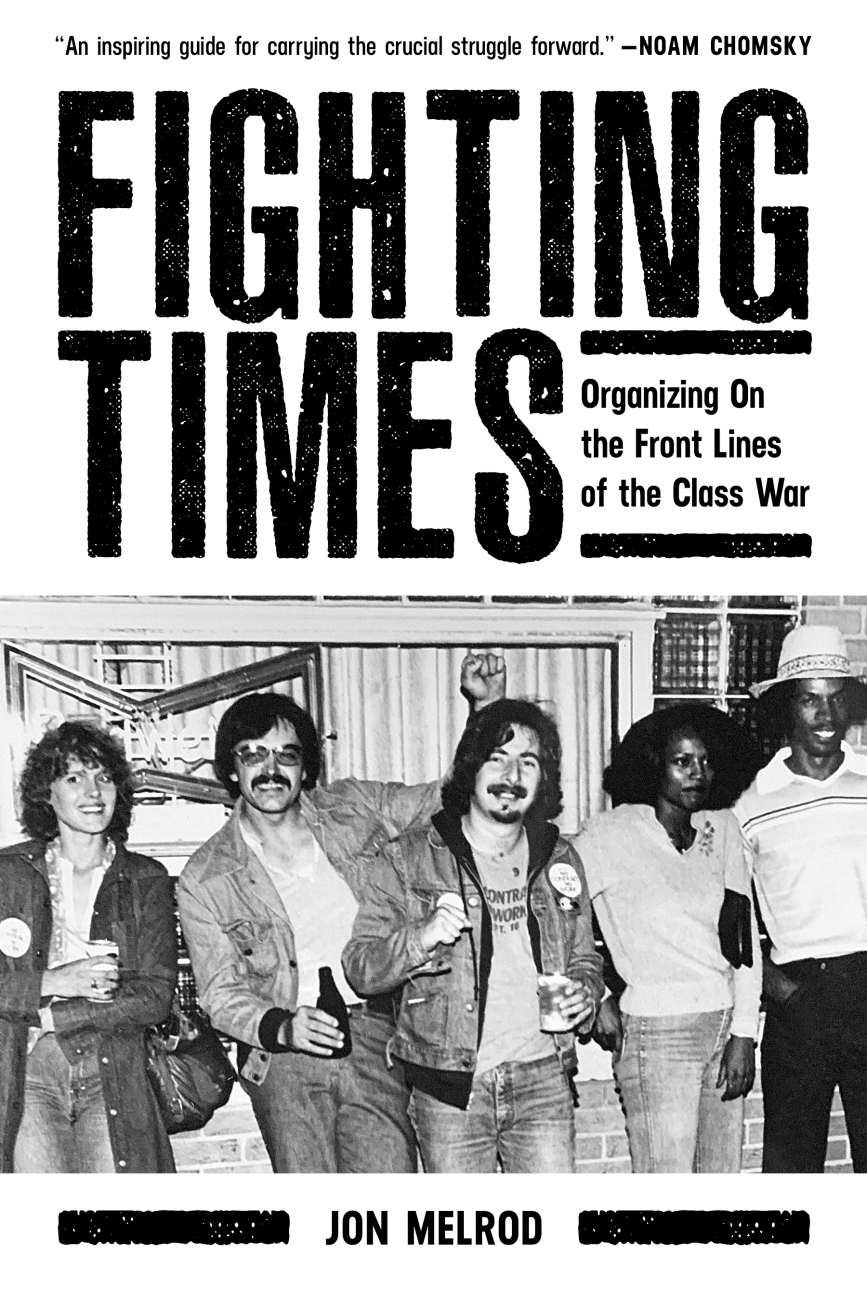

After a period of intense involvement in the student movement against the Vietnam War, and in solidarity with the Black Panthers, Melrod chose to find employment in a factory. He spent thirteen years of his life as an industrial worker, most of them as an employee of American Motors Corporation (AMC) in Wisconsin. His aim was to transform Local 72 of the United Auto Workers (UAW) “into a model of union militancy, rank-and-file democracy, and progressive political action.” During his career as an autoworker, Melrod was one of the leading actors of a caucus of dedicated activists who published the Fighting Times newsletter and organized various actions to improve working conditions, raise the level of political consciousness, and fight against sexism and racism.

Melrod grew up in an all-white, largely Jewish neighborhood in the racially segregated Washington, DC, of the 1950s. After graduating from an uptight boarding school in Vermont, he enrolled at University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he got deeply involved in student politics. He joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) in 1968, when the organization was at its peak.

With the local SDS chapter, he protested the campus institutions that supported the war in Vietnam. He also supported the Black People’s Alliance, a group of black students fighting discrimination, and helped the Black Panther Party spread its ideas. Melrod’s campus activism culminated during the May 1970 national student strike in reaction to Richard Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia. Although the strike led to impressive mobilization, it eventually fizzled out.

His diploma in hand, Jon Melrod decided to “leave the ivory tower behind” and move to Milwaukee, where he planned to “sink the deep roots necessary to galvanize the formation of a class-conscious, radical, working-class movement.” Although the decision to enter factory life was very much part of strategic discussions among far-left activists at the time, Melrod recognizes that it was also influenced by revolutionary romanticism: “I approached the new experience with the wide eyes of a youthful romantic joining Marx’s proletariat.”

Union Life

Anxious that he would not fit in because of his student background, Melrod quickly realized that the daily reality of hard work on the assembly line created organic camaraderie with his fellow workers. Nonetheless, throughout his career as a factory worker, he was conscious of the need to build trust and friendship by spending time with his colleagues outside of work, in the places where they hung out and in events organized to strengthen social bonds (and to overcome divisions based on race, sex, and department).

Most of Melrod’s industrial life was spent at AMC plants in Milwaukee and Kenosha. Like other radicals who set their sights on factories with a reputation for militant action, he was enthusiastic about joining a workplace with a long tradition of progressive unionism as well as a recent history of wildcat strikes (“Those stories called out to me like Mecca beckoning the faithful”). By contrast, his shorter stays in nonunion workplaces convinced him that they left little room for political action: “I needed to be in a workplace with a union — even a lousy union — where people had a sense of organization.”

At AMC, Melrod’s preferred vehicle for action was the rank-and-file caucus. Inspired by similar caucuses from the 1930s, the caucus at AMC was made up of a small number of committed activists who were independent from the union, but who were still willing to collaborate with combative elements within the official union structure. They published the Fighting Times newsletter, which mostly agitated on local issues but also touched on broader trends that would impact the workplace, such as automation.