By Juanjo Andres Cuervo

The Prisma

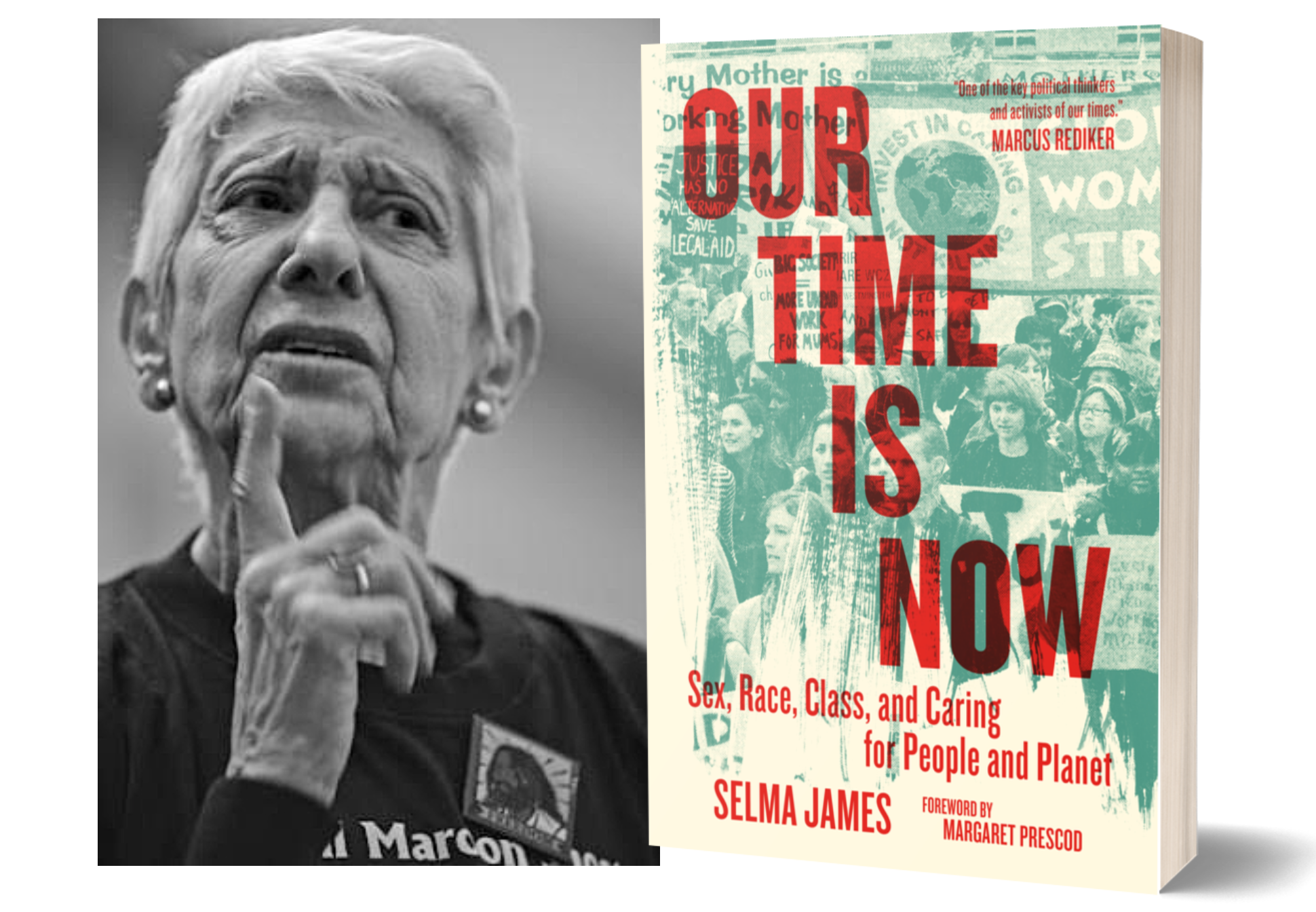

There are few people alive who have spent a lifetime as politically involved as she has. She is 91 years old, the founder of Wages for Housework Campaign, and has fought to end institutional racism and gender inequality. Her life is the epitome of a constant struggle for a new world based on international solidarity.

Born in Brooklyn in 1930, she lived through the Great Depression, the Second World War and the Cold War. She was just a kid when she became involved in supporting the Republicans in Spain who were fighting against Franco’s fascist army.

She realised very early in her life that she would be committed to political activism. “I knew that when I grew up, I would be part of the movement”.

Selma James, who is also co-ordinator of Global Women’s Strike was interviewed by The Prisma at the Crossroads Women’s Centre in Kentish Town, a place of safety and self-help services for women where many different organisations are based.

There is a feeling of political activism inside the building. Images and biographies of Lilly Connolly, James Connolly and Hugo Chavez are placed across the walls, alongside many newspaper articles in frames. Selma James, who had a meeting before the interview, has written some of them.

When I met her in one of the rooms upstairs, she greeted me with a smile that was also in her eyes.

Despite her long-time commitment as an activist, her genuine humility impressed me. Selma James is a person who asks you questions, listens attentively, and does not conceal her amusement.

When she introduced herself and told me that she could not give me her right hand because she felt some pain in it, I replied that I always prefer the left, and she burst out in a laugh, as she did several times during the interview.

She showed a great interest in learning about The Prisma, about myself and the situation in Spain, my home country and a region which she knew from an early age.

It was 1936, after Franco’s coup d’etat, when she went on her father’s shoulder to a demonstration in support of the Spanish Republic, beginning a long life of activism. 86 years later, she is still fighting against injustices, standing against racism and to erase the split between men and women. Because she does not conceal her hyperbolic language when she states that “it is a disaster, it is a tragedy that the two sexes don’t live their lives together.”

The socio-political and economic structure of a capitalist society establishes a patriarchal system in which women are forced to be at home to care for the family. Selma James has always struggled to “end capitalism”, and she is credited with coining the concept of “unwaged labour” to define the work done by the housewives who have no income of their own.

It was within that juncture that her famous text “A woman’s place” was created. Published in 1953, it discusses “a housewife’s perception of life at home and in the factory” and “the relation between women and men.” But why did she decide to write the pamphlet? After an experience which left a lifelong impression: one afternoon she went to a neighbour’s house and saw that all her children’s clothes were hanging from a line.

When she asked her what she was doing she replied that she was selling them because she had no money.

This story depicts perfectly the reality faced by housewives, unable to sustain an economic living by themselves, despite all their sacrifices to take care of the children.

Thus, “A woman’s place” was written to denounce “the struggle within the working-class that nobody talks about.” That is, the split between men and women.

Her experience during the thirties and forties were fundamental in developing her critical thought and political commitment. In 1945, she joined the Johnson-Forest Tendency, a Trotskyist organisation, and met the historian C. L. R. James, who later became her husband.

Selma liked his political ideas and his commitment to changing the world. “He thought that we could win, and of course, I wanted to stay with the winners”, she started to laugh out loud.

But suddenly, her face grew sombre, as she recalled an event in 1945, which was a watershed moment in her life. On her fifteenth birthday, 15th August, she was told that two atomic bombs had been thrown in Hiroshima and Nagasaki a few days before. She knew that the world had changed and that she would be part of a movement to deal with this new world.

In this first part of the interview with The Prisma, Selma James talks about her origins in Brooklyn in the 1930s, her political affiliation and the womens’ struggles.

How did your childhood shape your political consciousness?

I was born in 1930 and that was the beginning of a very political decade, so I grew up in the movement. My father was a lorry driver and was involved in organising with lorry drivers and with women in the factory. All my family was committed to the movement.

When I was 6 years old, I was on my father’s shoulder during a demonstration in support of the Spanish Republic. The women in nursing uniforms were carrying an enormous red banner, and people were throwing money at the banner to send it to Spain. I never forgot that. It thrilled me that far away, workers like us were fighting for power. Â Not many years had passed since the October Revolution of 1917.

I was organising the children of my age, collecting cigarettes packets because they had silver paper, and we made balls of the silver papers. My family was doing that, and we the kids were supporting them to send bullets to the Republicans in Spain. There was an atmosphere during the 1930s of antiracism, the organisation of unemployed people and the women who fought for home relief. After years of struggles, Roosevelt initiated this welfare mechanism. That was when I realised that we get nothing except with struggle.

This was my background, and I knew that when I grew up, I would be part of the movement to change or end capitalism, and for us working-class people to rise together.

In the 1940s, you became part of a Trotskyist organisation.

It was 1945, I went to a youth group, and I found the Johnson-Forest Tendency, where my older sister had been involved. Moreover, C. L. R. James was part of this group and I liked his political ideas. He thought that we could win, and of course, I wanted to stay with the winners.

That same year, the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It was on the 15th of August, during my 15th birthday, that I was told about that. I knew that the world had changed, and I was glad to be part of a movement to deal with this new world.

How did those years of activism influence you to write “A woman’s place”?

At that time, I had a child and a husband, who was one of the factory workers. I saw the housewives like me in the neighbourhood but they were not in the same organisation as myself. I saw their own struggle, which was different from the one in the factories. But I witnessed my mother’s struggle in the neighbourhood, and I was very interested in what these women thought, and how they expressed their struggles.

One afternoon, I went with my little boy to a neighbour’s house. I entered her living room, and saw all her children’s clothes were hanging from a line. I thought she had gone mad. So, I asked her “Why are these clothes hanging?”. She replied to me: “I’m selling them because I don’t get any money of my own, I am going to go crazy.”

I just realised that there was another struggle within the working-class that nobody talked about.

That is the struggle of women. I mentioned this to C. L. R. James who told me that I should write a pamphlet to express those ideas.

Some months later, he asked me if I had written the pamphlet. I said no, because I did not know how to.

“It is simple”, he said to me. “You take a shoebox and you make a slit at the top. And every time you think of something, you put it on a piece of paper, and you put the piece of paper in the shoebox. Then, one day, you open the shoebox up, and you see, you have a pamphlet.”

It worked, and that is how “A woman’s place” came to be. My mother liked it, and even today it is still good. It is a housewife’s perception of life at home and in the factory, because I went back to work when my son was 2 years old. However, it is mainly about the relation between women and men and the fact that they live different lives. This is a disaster, it is a tragedy that the two sexes they don’t live their lives together, most of the time they are separated.

(Next week: Part two)