By Kim Kelly

Philadelphia Inquirer

The recent vote to unionize at a Staten Island Amazon warehouse should be a reminder that Philly is and always has been a union town.

The recent news that workers at a Staten Island Amazon warehouse voted to unionize should be an inspiration to workers around the country, including in our region (where it must be said, there are already plenty of Amazon facilities ripe for unionization). Philly is and has always been a union town, thanks to the strength and determination of generations of workers, who have always fought like hell for what they deserve and whose blood, sweat, and tears have powered this city for centuries.

With an eye toward the future, here are five labor leaders from our city’s past that today’s workers should look to for inspiration as they continue the fight for a better world:

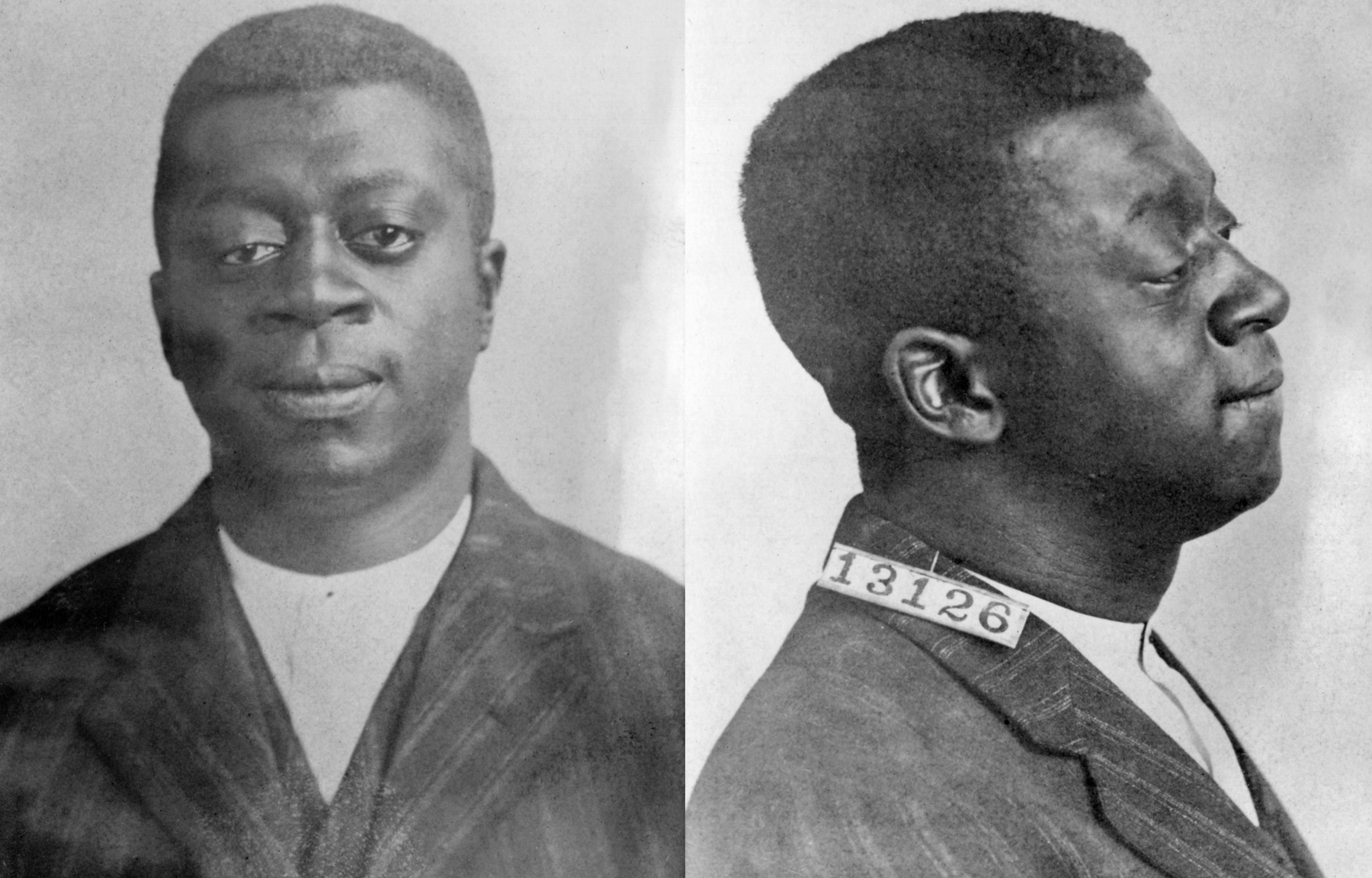

Ben Fletcher

Who he was: Born into a vibrant multiracial neighborhood in South Philly in 1890, Fletcher worked days as a longshoreman and spent his nights organizing for working-class liberation. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World, an anticapitalist union that welcomed all workers, and became a key organizer for Local 8, a dockworkers’ union of Black workers and Irish and Eastern European immigrants. As historian Peter Cole notes in his bookBen Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly, Local 8 voluntarily integrated itself 51 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, built itself up into a strong and effective multiracial union, and ruled the Philly waterfront for nearly a decade.

What he did: Fletcher traveled the East Coast organizing workers. In one harrowing incident, he narrowly escaped being lynched in Norfolk, Va. He was unflappable, charismatic, and wholly committed to the cause; unfortunately, in 1917, the U.S. government decided that he and his fellow IWW members had become too dangerous and arrested them during an anti-leftist sweep known as the Palmer Raids. Fletcher was tried for espionage and sedition in 1918 and sent to the United States Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kan.; he was given 10 years and a $30,000 fine. His sentence was commuted in 1922, and as soon as he was freed, he dived right back into organizing.Advertisement

What we can learn: This fearless son of South Philly dedicated his life to labor, and his story should teach today’s organizers that we truly are stronger together. Organizing across race, gender, ability, and generational lines is the key to winning the class war.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/PV2ONC55H5CAHAAMOM4AQHM6F4.jpg)

Mother Jones

Who she was: Mary Harris Jones was born in Ireland in 1837, and if the hand of fate had nudged her a bit differently, she would have lived her life there, or would have died young in the Great Famine during the 1840s. Instead, she survived to become one of the best-known labor figures in American history, living a long and eventful life that spanned three countries and endless struggles in the coalfields, factories, and railroads. For the last three decades of it, she answered to only one name: Mother Jones.

What she did: Though Mother Jones is perhaps best known for her roles as a United Mine Workers organizer, public speaker, and self-described hell-raiser, she was also devoted to the cause of ending child labor, a crusade that brought her to Philadelphia in 1903. At the time, Pennsylvania employed the highest number of child laborers in the country, with 120,000 children working in factories or coal mines. That July, she mustered a “children’s army” of about 300 juvenile mill workers and supporters at City Hall and led them on a march from Kensington to New York, where they intended to visit President Theodore Roosevelt at his summer home in Oyster Bay and demand he give her and three Kensington boys an audience. While the president refused, the March of the Mill Children made child labor a topic of national discussion and helped usher in labor law reform. A blue historical marker now stands at City Hall marking their journey and commemorating their commitment to a fight that continues globally.Advertisement

What we can learn: As of 2021, there were about 160 million children involved in child labor around the world; half of them are between the ages of 5 and 11, about the same age as the tiny coal miners and factory workers Mother Jones tried to save. Some things are always worth fighting for, no matter how long it takes to win.

Anna Geisinger

Who she was: Kensington is now one of the city’s more complicated communities, but during the 1920s and 1930s, it was known for its silk stockings. It was a working-class enclave that functioned as a booming mill town plopped in the middle of a big city, and was populated by hosiery factory workers. It was also the birthplace of the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers (AFFFHW), a socialist-led labor union; its first female organizer was hosiery worker Anna Geisinger. The union built worker power in and outside the Philadelphia city limits; its Kensington home base, Branch 1, had an outsize impact on labor history, and especially on the early development of labor feminism.