By Paul Buhle

Rain Taxi

April 2022

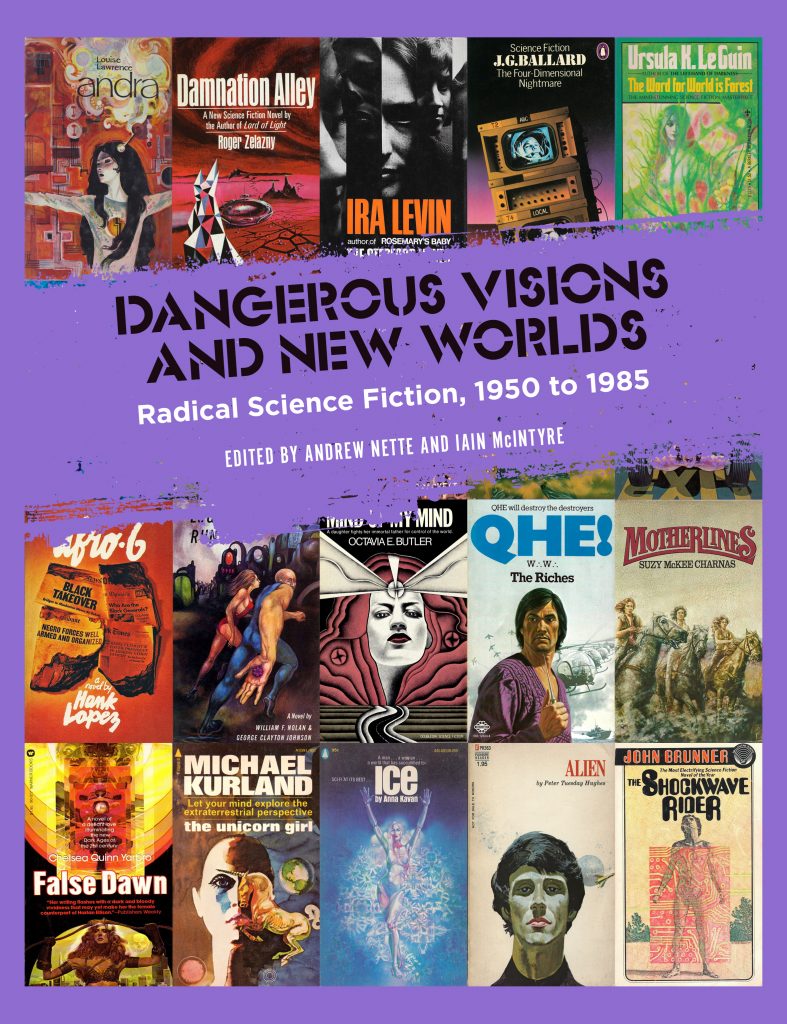

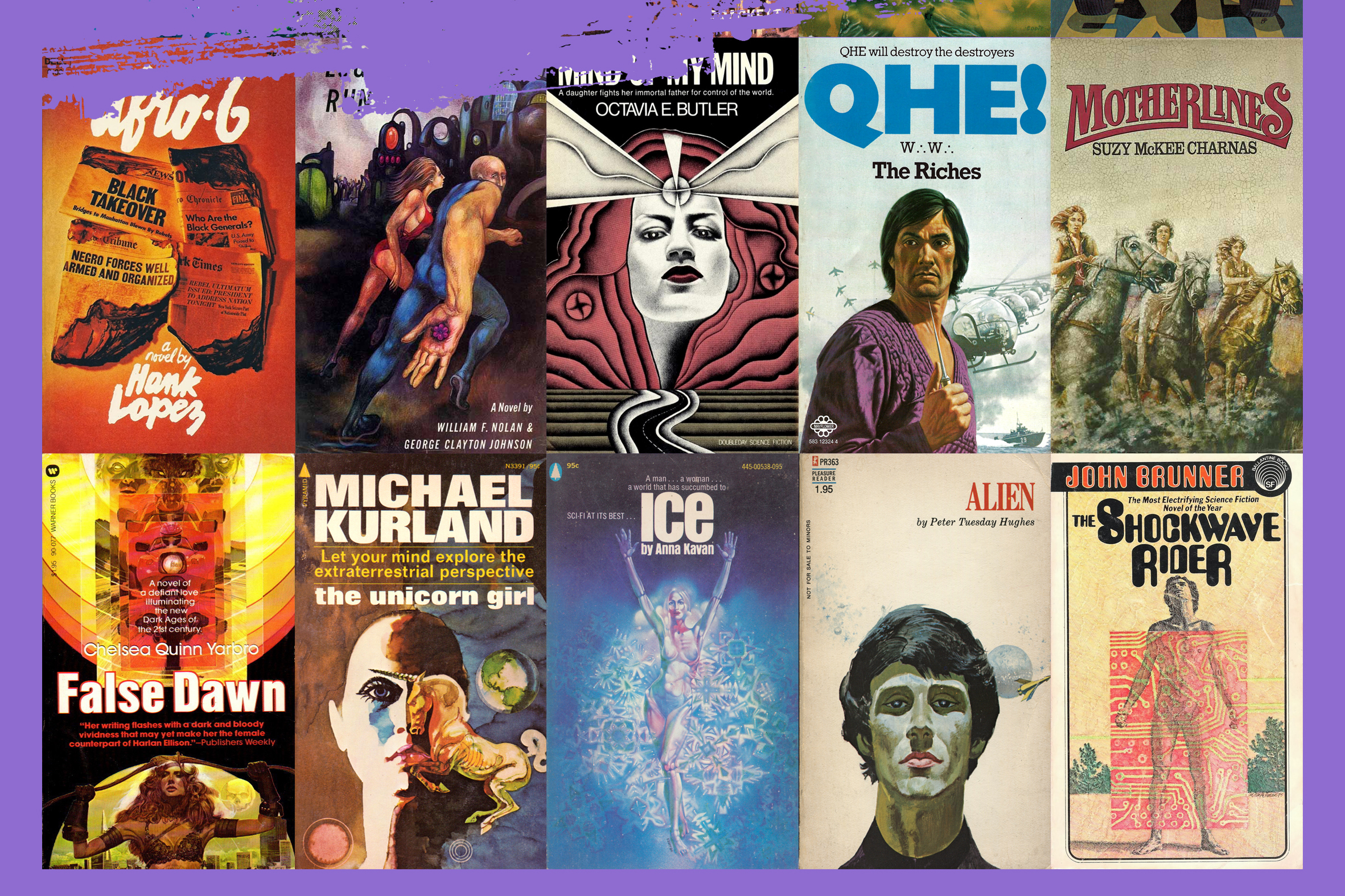

About a half century ago, my grand aspiration was to become a Science Fiction writer. It wasn’t a bad idea. The half-dozen or more SF or SF/Fantasy magazines on the newsstands published hundreds of stories each month, and the paperback market was similarly booming. Some of the 35-cent paperbacks tackled serious subjects, like the commercialization of culture; the more avant-garde writers offered literary polemics against racism and war. And although I couldn’t see it, the revolution had only begun. PM Press’s recent anthology Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985 covers the field’s early years with wonderfully sweeping essays and studies of some of the most illuminating authors and editors of the field in transformation.

From a radical point of view, the “Futurion Club” of Manhattan, formed during the Popular Front years of the later 1930s, offered a beginning. Comprised of mostly Jewish writers, it included Isaac Asimov (the only genre writer, along with Rod Serling, to have a whole magazine eventually named after him), but also figures like Donald Wohlheim, destined to become more influential as editors of SF magazines and of their own paperback imprint series, and Judith Merrill, the feminist writer who anticipated so much to come.

One of the astounding and revealing documents in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is a reprint of two facing pages of writers for and against the U.S. invasion of Vietnam. This literal face-off is useful because it stands for so much more. The audience for magazines and books, until at least 1960, was considered either juvenile or juvenile in mind, a similar assumption to that made about comic art and similarly maddening to more mature creators and fans. Bug Eyed Monster traditions had been nibbled at the edges by writers who managed to suggest that encounters with aliens might be a lot more complicated, or that civilization after a widely anticipated nuclear war might not rebuild by the same rules, or that the State—even the U.S. State—might be dangerous for individual liberty. That last point cut across Left and Right, reaching a rapidly expanding fan base and offering promise to a relative youngster like Philip K. Dick, an anti-authoritarian who could seemingly be Left and Right at the same time.

But another issue had more potency for the Science Fiction of the 1960s and after: Sex. One much-remembered writer, Jose Farmer, had a global impact on SF authors with his daring plots and suggestive details. Meanwhile, the judicial repeal of censorship laws offered cash galore for the small-scale producer as well as for the more daring movie corporations. One of the most intriguing essays in Dangerous Visions and New Worlds reveals the creation of soft-core lines of SF books with circulations in the tens and hundreds of thousands. This was a boon to enterprising authors who could grind out lascivious wordage at record speed, including prolific gay authors such as Larry Townsend. Older readers who shunned sexual material expressed shock at even muted effects on the mainstream writers and magazines. Those older readers counted for less and less as the counterculture advanced, however.