By Jon Frankel

Green Mountains Review

March 2022

“And I was silent, ecstatic in the cradle of real things.” —Retouch/Switch

I met Cara Hoffman in 1999 when we were featured at downtown reading series in Ithaca, New York. I had already read the manuscript of her novel, Running, which wouldn’t be published until 2017, and she had read my first novel, Specimen Tank. She was in her twenties and I was thirty-eight. Mutual friends had been telling me I needed to meet her for months. I was skeptical that her first book could be as good as they said it was, but within a few pages I was stunned by the precise prose and her savage sense of humor.

Cara was cut pretty rough in those days and older writers were falling over themselves to discover her and polish her up. She was getting a lot of bad advice from local authors, professors and an agent in New York who insisted if she revised her manuscript to his specifications, he would sell it for six figures. He told her, among other things, to humanize her protagonist by making her cry and look more feminine. Cara was contemptuous of this advice and walked away from it, one of the smartest things she ever did.

A troublemaker who grew up in a family of brothers, she had spent years traveling, and getting by on very little and she was, in those days when I first met her, a drinker. She once wrecked a meeting with an eminent Cornell author and professor who was interested in her work by getting drunk and making fun of Cormac McCarthy, and telling him he looked like the Marlboro Man. She was also the most ambitious writer I had ever met, certain that she would succeed. And her plan was to succeed without compromise. She even made me believe I could do that. She still does.

Being a working class writer with no college education and a GED meant poverty. It was not genteel, Romantic poverty. She gave birth in Buffalo on Medicaid, had an emergency C-section without anesthesia, an experience that would sear itself on her psyche. She worked as a journalist and covered a local environmental disaster as well as the rape and murder of a young woman, and other crimes. As an autodidact committed to making art on her own terms, she worked a succession of shitty jobs. For a while we both worked at Cornell University, Cara as a museum receptionist and I as a bookshelver in Olin Library. On breaks I would go and hang around her desk in the museum lobby, pissing off her bosses, and she would find me in the stacks, where we would hide out in the aisles laughing too loud. Eventually she became a grounds worker, applying pesticides. I stayed at the library.

To this day I don’t consider a work done until Cara has commented on it and I am still, after more than twenty years the lucky recipient of her works-in-progress. Cara lives in Exarchia now, so we meet rarely and when we do we walk for miles, usually in the city, visiting bookstores, Chinese noodle shops, and cafes. Our conversations are focused on writing: the art of writing, the technique of writing, what we love about writing, what we hate about the business of writing.

With Running in limbo, and no more agent, she turned to the short story. The first story she wrote was “Strike Anywhere” which got her a NYFA Fellowship. She used the money to rent a studio on a pedestrian mall, which at the time still had old, cheap loft spaces. There was no bathroom, but tall windows in the back. She had a 1960s portable record player and played Bowie at earsplitting volume. I had never seen her happier. She moved to the country and worked as a bartender, living in a farmhouse that had been stripped to the studs, joists and rafters except for one room: a cherry-paneled library, where a man she liked at the time sat pretending to read Heidegger. It wasn’t a total disaster. The extremity of the situation appealed to her, and she read a lot, and it was there she gathered the material for So Much Pretty, the book that would change everything.

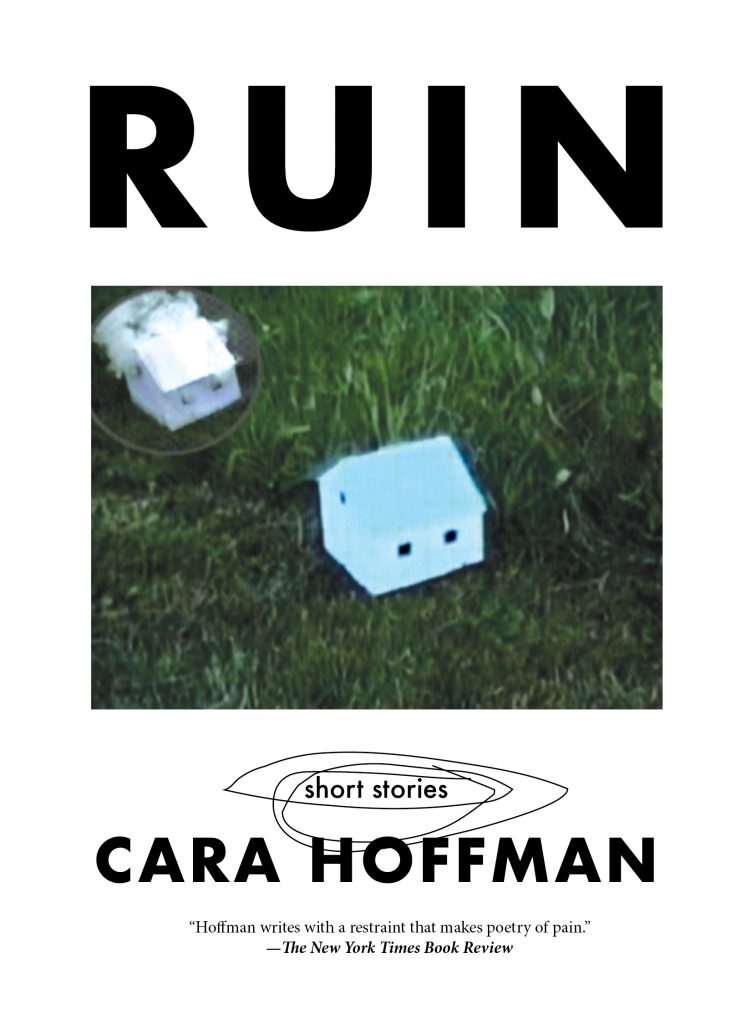

Cara wrote the remainder of the early stories that appear in RUIN during a residency at the Saltonstall Foundation. Rereading them 14 years after, I am again amazed. Running (as it then existed) rode on a blast of youthful energy. These stories drill down into her craft, and her heart. In “They” Cara describes the physical world of the mice in such detail it feels as if her eyes are microscopes: ‘…blades of light radiating in from around the nails that shot through her room. They were like rays of a black centered sun.’ “Childhood,” the funniest thing she’s ever written, opens with: ‘It was my childhood dream to become either an alcoholic, or a very old man.’ The reversal of perspective allows Cara to eviscerate the old man-child’s parents’ ‘ambitionless materialism.’ Her work is full of ghosts and dreams. She writes with the eye and ear of a scientist and a poet. In “The Paragrapher” she describes snowflakes as ‘cold white ghosts of fingerprints raining down on her cheeks.’ Childhood and family are Cara Hoffman’s muse. Six of the nine stories are about childhood and children. “Waking”, a lyrical celebration of girlhood, friendship, and the feeling that anything is possible, is shattered by adult insight, the waking of the title: ‘This whole beautiful world,’ she said, tears running down her face at last, as she grabbed the collar of my shirt, ‘is a lie.’

Cara used to refer to her style as documentary, which she learned working for the Buffalo radical journalist Joe Schmidbauer, who figures prominently in “The Paragrapher.” “The Young Guard” is a perfect example of the documentary style. Set in a kibbutz during the Lebanon War, the six-year-old protagonist further develops another of Hoffman’s concerns: violence, masculinity, and war. Her male characters are almost always wounded in some way by war and violence. Some go on to perpetuate it, like the unrepentant killer David/Declan in “Running”, powerful men who get away with rape and murder. Others, like PJ in “Be Safe I Love You” are kind and weary survivors. The boys of “The Young Guard” spend their time digging up unexploded shells and bullets. But they are still, quintessentially boys. They bomb around the kibbutz on their bikes and stop off at one boy’s mother’s apartment: ‘She’s not there, so they eat all the sugar cubes in the bowl on the table.’

While some of these stories prefigure the work for which she is now known, they stand on their own; they are not just studies and drawings for a later canvas. She uses the short story form to experiment and explore beyond the confines of American literary fiction, and the later work continues this. Unlike so many bland commercial literary writers she does not rewrite Lolita from Lolita’s point of view. These are not clever post-modernist retreads, stories about professorial adultery, bored humans in high rises dissatisfied with the legal profession, or reimagined histories. Cara has no time for the dull sophisticated, perfect narratives that refuse to examine the conditions of working people, the poor, the marginal, and genuine rebels who refuse to give in to the leveling idiocy of Capitalist ‘culture.’ They are defiant works of art that assert, that assume there is another culture not tuned to nationalism, ideology, resentment, profit—that assume a common endeavor that is the true human project. There is humor and love in these stories, love of family, of eccentrics, of food and sex, of life because liberation is joyous.

Cara once told me that my science fiction was Utopian because I assumed there would be people around in 500 years. Well, for the sake of fiction, I have to believe that. And I hope they will be reading Cara Hoffman.