By Kevin Adams

College and Research Libraries Journal

March 2022

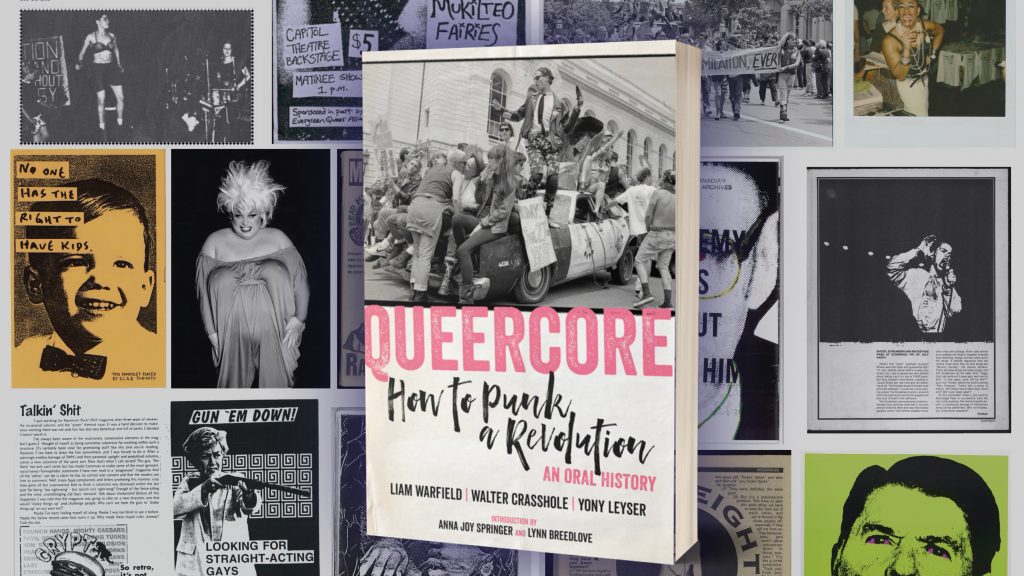

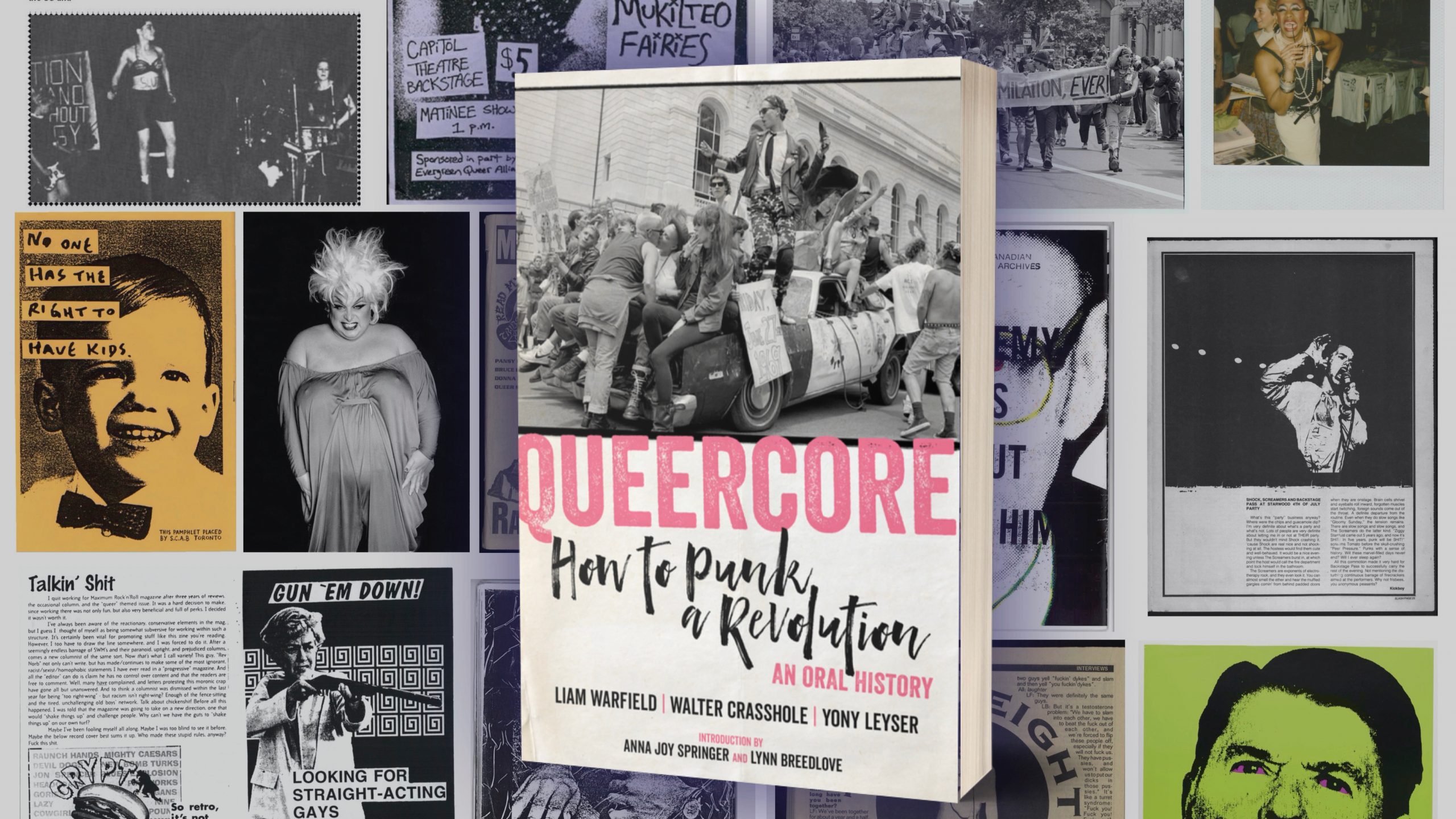

Queercore: How to Punk a Revolution: An Oral Historytells the stories of queer punk, primarily in North America from 1969 to 1999, by constructing a narrative from the movement’s media (zines, records, and films), personalities, politics, and activism. The book is a snapshot of voices from many

perspectives across this period of queer punk, and the imagery and voices are as graphic, explicit, and colorful as you might expect. Queercore springs from hours of interviews that were conducted originally for a film by the same name created by Leyser. The book’s editors used the remaining footage and dialogue to put together this work. The messy nature of history and punk are embodied by the oral history’s chorus of diverging voices.

They come together in this volume to form a cohesive narrative covering several key themes: 1) defining queercore; 2) the history of queercore from 1969 to 1999; and 3) the media that made the movement. This book is of value to LIS workers on multiple fronts, particularly in the context it provides for archivists and librarians who specialize in alternative information resources and subcultures. Additionally, the book lays out a variety of activist and antifascist strategies for creating space for marginalized voices, something library workers at all levels ought to prioritize.

Throughout the book, movers and shakers from queercore comment on a key question: “What is queercore?” The term represents a shift from “homocore,” the title of a Toronto zine.

The change in terminology is recognized by some members of the scene more readily than by

others. The transition was meant to expand inclusivity in the movement, representing a shift

away from the image of the gay white male punk. As with any subculture, queercore is not

a monolith. No clearcut definition emerges in the book, though a broad consensus is that the

movement was created by and for punks who were too queer for other punk scenes and queer

folks who were too punk for their queer communities.

Warfield recognizes that this book is not a comprehensive history of queercore. In fact, the

dates that the book covers are relatively arbitrary. The reality is that queer and punk individu-

als and subcultures have existed together prior to 1969 and are alive and well in the present

day. The oral history focuses on the key creators in these decades from queercore hotspots,

especially San Francisco and Toronto. Each scene developed differently, but each was fabri-

cated in some sense. And each had to fight to exist, creating new narratives and pushing the

boundaries of accepted language and imagery inside and outside the mainstream. This history

proceeds from the inception of these scenes to their development through punk shows, zine

creation, and activism throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Topics covered include the AIDS crisis

and ACT UP, antifascist and political tactics, punk machismo and the development of Riot

Grrrl, co-optation and assimilation, clashes between the scene’s larger-than-life personalities,

and the diverse media of the movement.

Fundamental to the narrative is the influence that alternative media had on these scenes.

Chapters focus on queercore music, performance, films, and zines. The creators of two key

zines, Homocore and J.D.’s, are heavily featured in this book. Following the establishment of

these zines and the proliferation of many others, queercore zinesters came together at conventions where members of different scenes met and collaborated. The main queercore conventions

highlighted in this book are SPEW and Homocore Chicago. Among many others, key voices

included in these pages are Bruce LaBruce, Vaginal Davis, Tom Jennings, Brontez Purnell,

Milo Miller, Jayne County, John Waters, Martin Sorrondeguy, and many others.

Some of the content in these pages feels contradictory and frustrating. One disturbing

theme throughout the book is a general distrust of younger generations, including a distrust of

present-day transgender youth and queer punk communities using the internet. This reviewer

was disappointed that there was often little enthusiasm for the direction that contemporary

queer punk scenes are moving and the ways they are organizing for change. In addition,

some readers may find the use of uncensored graphic language and imagery to be disturbing.

Overall, the book is a valuable source for any librarian or academic interested in the

development of alternative subcultures, specifically in queer culture, punk culture, and the

intersection of the two. For LIS professionals, the book provides vital context for archivists,

instruction librarians, and zine librarians who work closely with queer or punk zines. This

is bolstered by a set of annotated bibliographies for queercore zines, films, and records. A

theme throughout Queercore is the struggle to survive and create space. To do this, queercore

developed and deployed specific strategies that can inform librarians in the important work

of creating similar antioppressive and antiracist spaces.