by Signal

Signal: Dispatches

Decexmber 4th, 2021

This is the inaugural post for an ongoing series of short interviews with current political artists working around the world. We are very excited for our first interview to be with scientist, teacher, activist, and artist Jona Yang from the Philippines, whose arresting and very printer-ly works caught our eye and our attention over the last year. Jona’s answers are printed here in English and Filipino.

Will you tell us a little about yourself? Who are you? Where do you live?

Magandang araw, Alec! (Good day, Alec!)

I am Jona Yang, a full-time activist and the Secretary-general of AGHAM-Advocates of Science and Technology for the People (AGHAM is an organization of pro-people S&T professionals, bonded together to promote science and technology that genuinely serve the interest of the Filipino people). As of the moment, I am based in Quezon City.

Ako si Jona Yang, isang full-time activist at kasalukuyang secretary-general ng AGHAM – Advocates of Science and Technology for the People. Isinilang at lumaki ako sa Quezon City, Philippines.

What is important for you to convey in your artwork? What ideas or philosophies is your work built on? Can we walk through one or two images- for example ‘Free Mass Testing Now’ and ‘activism is not a crime’. What were these made for- what was the intention? How did you choose the images/subjects? What is your process like?

My serious attempt in learning printmaking started two weeks prior to the total lockdown imposed by the Philippine government in response to the rising cases of COVID-19 last March 2020.

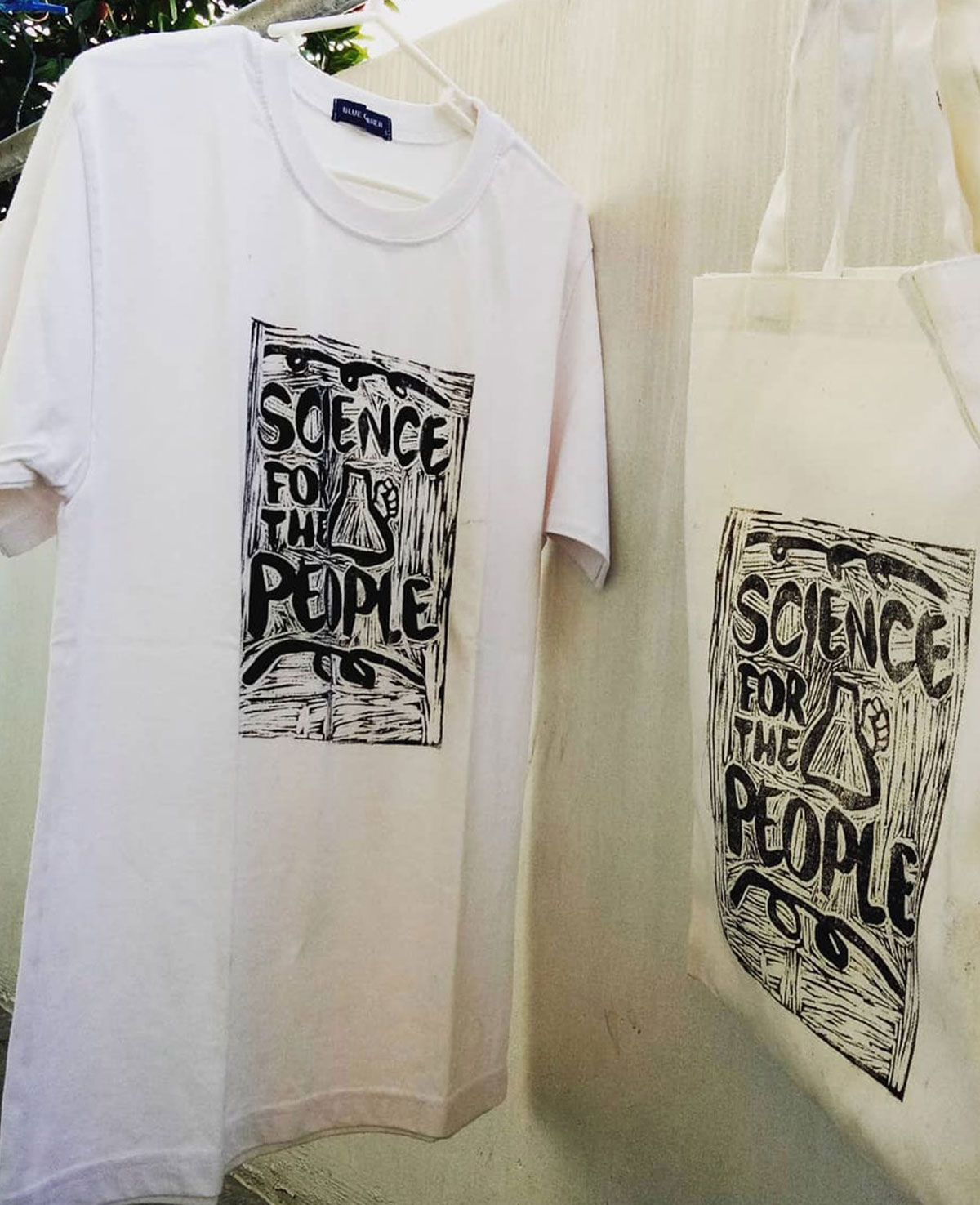

At first, I began carving to supplement my therapy for bipolar disorder and to produce prints related to my work as an advocate of pro-people science. My first print, Science for the People, was created before the pandemic last year as an homage to AGHAM and to all the activists from the science and technology (S&T) community who actively participate in pro-people campaigns on land distribution for poor farmers, protection of coastal ecosystems, support for local industries, and promotion of scientific culture for the people among others.

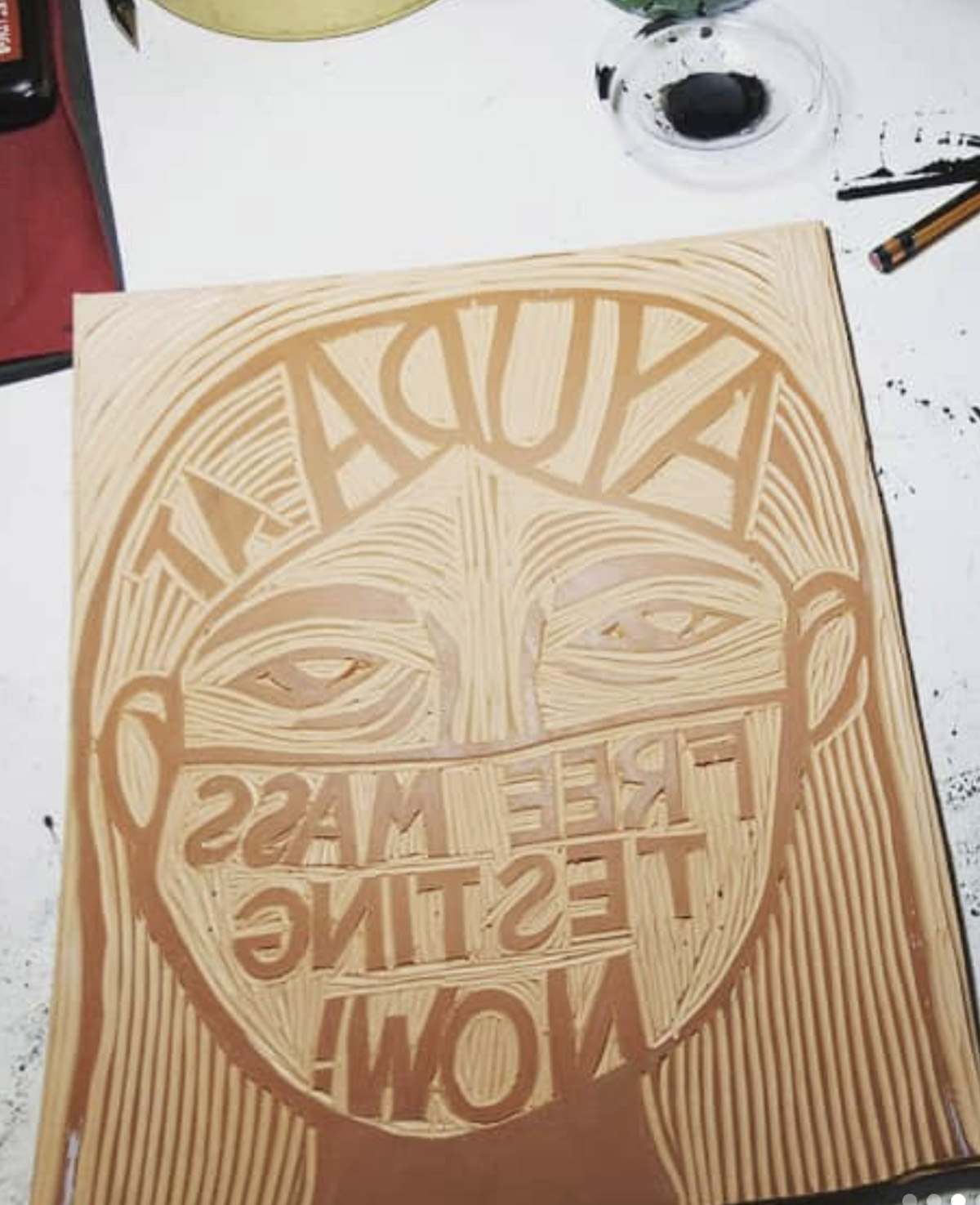

But as the militarist lockdown continued, coupled with the anti-people and unscientific pandemic response of the Duterte government, I realized the need to carve more prints, not just about my personal struggles, but are also reflective of our current material conditions. On March 16, 2020, the fascist Duterte administration ordered a total lockdown to purportedly control the spread of COVID-19 across the country. My second print, Mass Testing – Ayuda Now! (Mass testing – socio-economic relief Now!), was an attempt to echo the call of the Filipino people to launch mass testing and aggressive contract tracing in vulnerable communities with high cases of COVID, and to provide socio-economic relief to all Filipino families especially those who lost their income sources due to the strict lockdown restrictions. According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), more than ten million Filipinos lost their jobs in 2020. In essence, a tenth of our population experienced—and still experiencing—food insecurity in the middle of a pandemic. It would have helped to alleviate this situation if the national government had allocated a large budget for the socio-economic relief of the people and small business owners.

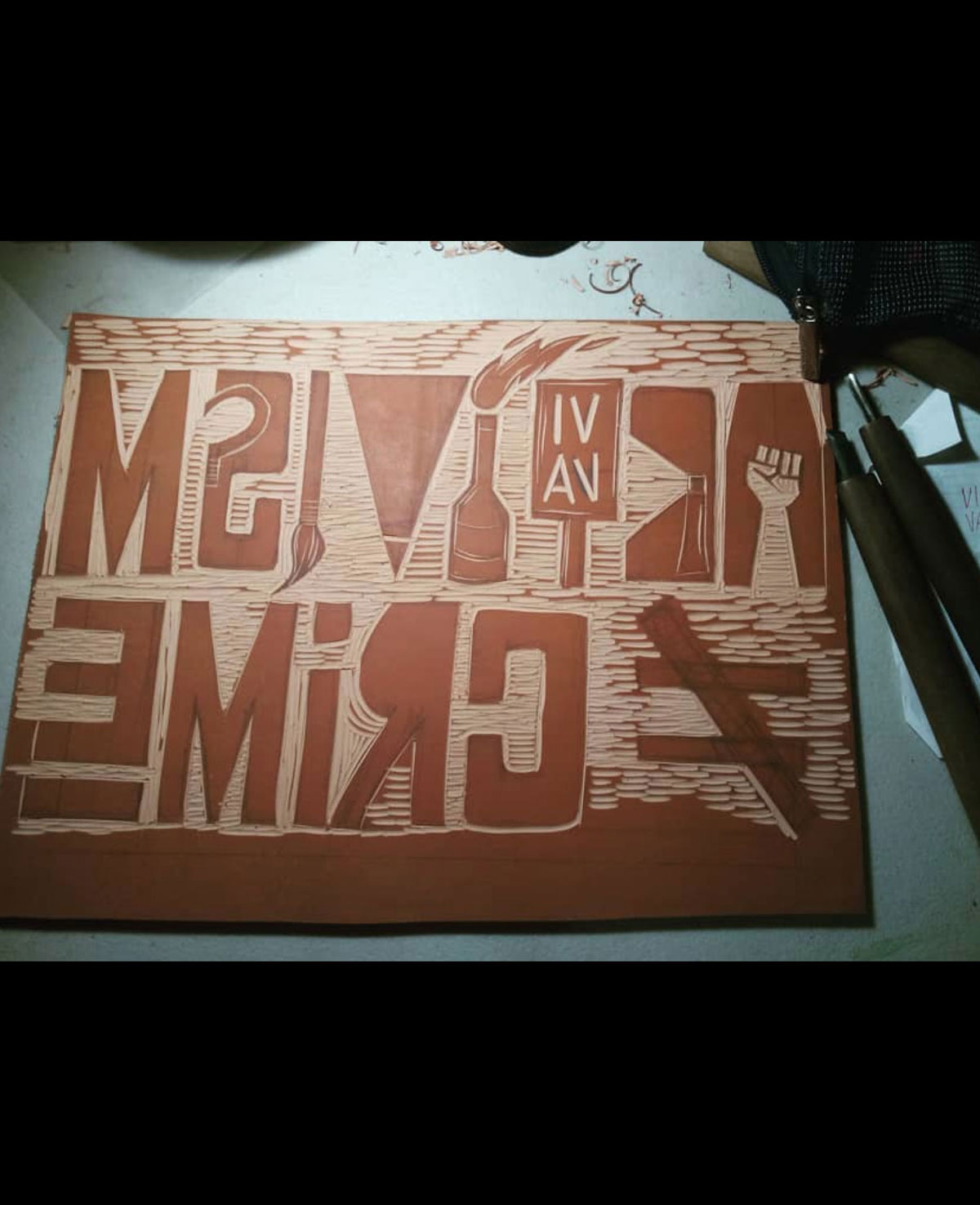

In June 2020, I created Activism ≠ Crime in response to the Anti-Terrorism Bill that became law (Republic Act 11479-Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020) the following month. In the midst of a health crisis due to the ineffective pandemic response of the national government, how did they manage to prioritize this law!?!

The Duterte administration has a long history of human rights violations. The violent crackdown on poor drug users has resulted in more than 8,000 deaths according to the Human Rights Watch. On the other hand, since Duterte’s term in 2016 until August this year, the human rights group Karapatan Alliance Philippines has recorded more than 400 cases of extrajudicial killings of political activists, half of whom are human rights defenders. The Duterte government is perpetuating a culture of fear and impunity. The passage of the Anti-Terrorism Act will further inflict human rights violations such as illegal intimidation, red-tagging, surveillance, arrest, torture, murder of government critics and ordinary citizens. And this has already happened to two Aetas, Jasper Gurung and Junior Ramos, who were illegally arrested in August 2020 for being suspected members of the New People’s Army. After 10 months of detention, the court dismissed the case because there was insufficient evidence against them.

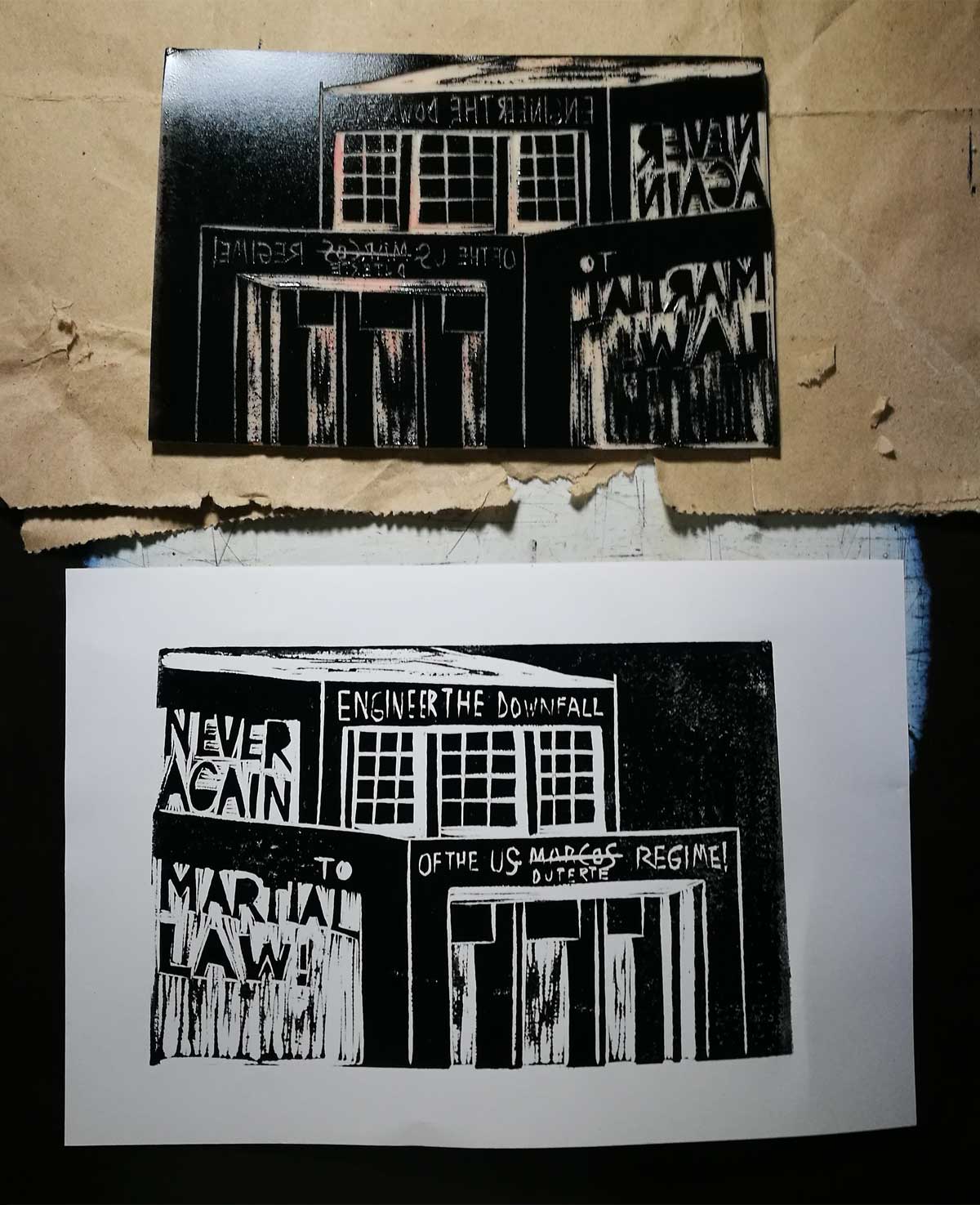

My latest print, Engineer the Downfall of the US – Marcos Duterte Regime!, is a tribute to the martyrs from the S&T community who fought against the Marcos dictatorship and to those who continue to struggle against the current fascist government of Rodrigo Duterte.

The print is inspired from a photo of Melchor Hall during the Diliman Commune (1971). At this time, the different engineering departments of the University of the Philippines Diliman were based in Melchor Hall. The call–Engineer the Downfall of the US-Marcos Regime!–that can be seen on the facade of Melchor Hall was a show of force from the engineering students against the Marcos dictatorship. As a tribute to all the activists from the S&T community who have dedicated their lives to topple down the Marcos dictatorship, I dedicate this print to honor their sacrifice.

Sinimulan ko ang practice ng printmaking dalawang linggo bago ideklara ng gubyerno ang total lockdown bilang tugon sa tumataas na kaso ng COVID-19 noong March 2020.

Sinubukan ko ang pag-uukit bilang bahagi ng aking therapy sa bipolar disorder at extension ng aking gawain bilang advocate ng pro-people science. Ang unang print na aking ginawa, Science for the People, ay nagsisilbing pagpupugay sa AGHAM at sa mga scientists-activists mula sa science and techonology (S&T) community na aktibong lumalahok sa mga pro-people campaigns gaya ng land distribution para sa mahihirap na magsasaka, protection of coastal ecosystems, pagtatayo ng mga pambansang industriya, pagsusulong ng makabayan, makamasa at siyentipikong kultura.

Sa pagpapatuloy ng militaristang lockdown, kasama na ang anti-mamamayan at di-siyentipikong pandemic response ng gubyernong Duterte, nakita ko ang pangangailangan na lumikha pa ng mga prints, hindi na lamang tungkol sa aking mga personal na suliranin, kundi tungkol na rin sa kasalukuyang kongkretong kalagayan ng mas malawak na lipunan. Noong March 16, 2020 sinimulan ng fascist Duterte administration ang total lockdown para raw makontrol ang pagkalat ng COVID sa buong bansa. Ang ikalawang print na aking ginawa, Mass Testing – Ayuda Now! (Mass testing – socio-economic relief Now!), ay isang pagsusumikap na i-echo ang panawagan ng mamamayang Pilipino sa gubyerno na maglunsad ng mass testing at aggressive contract tracing sa mga komunidad na mataas ang kaso ng COVID, at magbigay ng ayuda sa lahat ng mga pamilyang nawalan ng trabaho dahil sa strict lockdown restrictions. Ang kalunos-lunos na epekto nito ay mahigit 10M ang nawalan ng trabaho noong 2020 ayon sa International Labor Organization (ILO). Ibig sabihin, 10% ng populasyon ng bansa ang nawalan ng tiyak na pagkukunan ng pagkain sa gitna ng pandemya. Makakatulong sanang maibsan ang kalagayang ito kung naglaan ng malaking budget ang national government para sa socio-economic relief ng mga mamamayan at maliliit na negosyo. Bagamat naglaan ng budget ang gubyeno para sa ayuda, napakaliit nito para matugunan ang pangangailangan ng mamamayan.

June 2020 ko naman ginawa ang Activism ≠ Crime bilang tugon sa Anti-Terrorism Bill na naging batas na (Republic Act 11479 – Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020) noong sumunod na buwan. Sa gitna ng krisis pangkalusugan dulot ng palpak na pandemic response ng national government, paano nila nakuhang isaprayoridad ang batas na ito?

Mahaba na ang kaso ng Duterte administration sa paglabag ng mga karapatang pantao. Pakana niya ang marahas na anti-drug campaign sa bansa, at batay nga sa datos ng Human Rights Watch, umabot na sa higit 8,000 drug suspects ang kaniyang pinapatay. Ayon sa bilang ng Karapatan (Karapatan Alliance Philippines), simula nang umupo sa poder si Duterte noong July 2016 hanggang nitong August, umabot na sa higit 400 ang extrajudicial killings ng mga political activists kung saan kalahati nito ay mga human rights defenders. Pinapalaganap ng Duterte administration ang culture of impunity para matakot ang mamamayan. Ang pagpasa ng Anti-Terrorism Act ay lalong magdudulot ng mga human rights violations gaya ng iligal na intimidation, red-tagging, surveillance, pag-aresto, torture, at pagpatay sa mamamayan at mga kritiko nito. At nangyari na nga ito sa dalawang katutubong Aeta na sina Jasper Gurung at Junior Ramos na iligal na inaresto noong August 2020 dahil pinaghihinalaang kasapi ng New People’s Army. Makalipas ang 10 buwan na pagkakakulong, binasura ng korte ang kaso dahil hindi sapat ang ebidensya laban sa dalawang katutubo.

Ang pinakabago kong print, Engineer the Downfall of the US – Marcos Duterte Regime!, ay tribute para sa mga martyrs mula sa S&T community na lumaban sa diktaduryang Marcos at sa mga nagpapatuloy ng pakikibaka laban sa rehimeng Duterte.

Halaw ang print sa larawan ng Melchor Hall noong Diliman Commune (1971). Sa panahong ito, nakabase sa Melchor Hall ang iba’t ibang engineering departments ng UP Diliman, at ang panawagang iyan na makikita sa facade ng Melchor Hall ay ang matapang na tindig ng mga engineering students laban sa diktaduryang Marcos. Akin itong inaalay sa lahat ng mga aktibista mula sa S&T community na nag-alay ng kani-kanilang buhay para sa panlipunang pagbabago.

It appears that you make a lot of art for protests and social movements- can you tell us about that process for you? For example- do you make art the night before or plan far ahead? Do you work with others or by yourself?

I am just one of many activists from the S&T community who work together to produce relevant creative materials for the various people’s mobilizations we participate in. The S&T community formed Art ATAK – Artista para sa Agham, Teknolohiya, at Kalikasan (Artists for Science, Technology and the Environment) to spearhead the production of our protest materials. Often, the whole process of producing these materials takes a long time. Before the actual conduct of any protest action, the community would collectively work to brainstorm ideas, assign members to purchase the materials, delegate tasks on the actual production, etc. The whole process is a collaboration of the various mass organizations from the S&T community.

Isa lamang ako sa maraming activists mula sa S&T community na nagtutulungan upang makagawa ng relevant materials para sa iba’t ibang mobilizations na aming nilalahukan. Binuo ng S&T community ang Art ATAK – Artista para sa Agham, Teknolohiya, at Kalikasan upang pangunahan ang paggawa ng mga protest materials. Madalas, mahaba ang buong proseso ng paglikha ng mga protesta materials dahil sama-samang gagawin ng komunidad ang brainstorming, pagtutukoy kung sino-sino ang bibili ng mga gagamiting materials, sino-sino ang magpipinta at iba pa.Mula brainstorming, pagbili ng mga materials, hanggang sa pagpipintura ay collaborative effort talaga ng iba’t ibang mass organizations mula sa S&T community.

I love the density of your line-work in your prints- deep lines on the face, on the arms and fists, surrounding the quote from Mao. Is this a deliberate process? intuitive? experimental?

Thank you for appreciating the details of my works. The details were deliberate. Because of my tight work schedule as a full-time activist, the duration and process of creating a relief print is long and challenging. The detailed line work is a representation of the long meditative process of print production, as well as the long (but fulfilling) struggle for national liberation.

Maraming salamat sa pag-appreciate sa aking line work. Deliberate ang mga detalye. Matagal talaga ang buong durasyon ng paglikha ng isang relief print dahil sinisingit ko ito sa full-time activist work. Representation ng detailed line work ang mahabang proseso ng print production at sa struggle for national liberation kung saan aktibong akong nagpaparticipate.

How do you get your work seen? Street art? Art shows? Instagram? Protests?

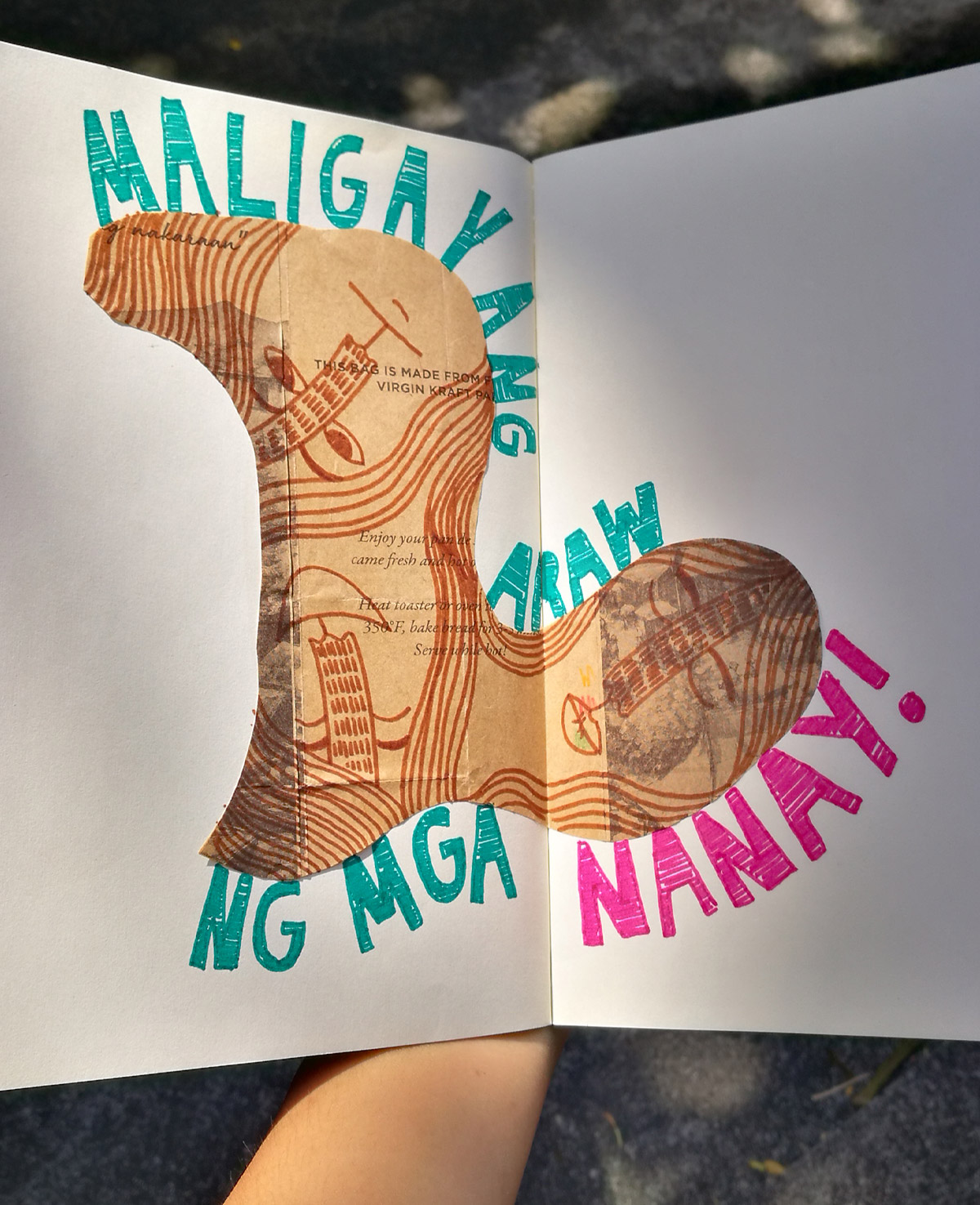

Mostly, I post my progress and finished prints on my personal Facebook and Instagram accounts. Recently I started selling prints to support my activist work. (Last year was a different story. Whenever I finish a print, I would give copies to my friends and neighbors. They have also allowed me to print on their cloth bags and t-shirts.)

My personal dream is to really improve on printmaking so that I can create more socially-conscious posters that reflect, not just the calls of my community, but also the calls of our toiling masses.

Mostly, sa aking personal Facebook at Instagram accounts. Recently ay sinimulan kong magbenta ng mga prints para suportahan ang aking activist work. Pero noong nakaraang taon, nakipag-collaborate ako sa aking mga kaibigan sa printing ng prints sa papel at tshirts.

Personal dream ko talagang humusay pa sa printmaking nang makapaglikha pa ng mga socially conscious posters na nagrereflect, hindi lamang ng mga usapin ng aking komunidad kundi pati na rin ang panawagan ng masang anakpawis.

Are you working on any projects right now that you are excited about and want to share?

As of writing, I am in the middle of carving out a tribute print for political artists Professor Leonilo “Neil” Doloricon and Parts Bagani who both died this year, the former died due to natural causes while the latter was brutally murdered by the government. Their life and works are central to my learning process as a printmaker.

Aside from continuing my tribute print, I am also preparing myself for another batch of prints that I will sell as part of a fundraising effort. After this, I am planning to work on other prints that, hopefully, will be finished before the 2022 National Elections. In this election period, disinformation offensive on social media is on the rise to propel the victory of Bongbong Marcos, the son of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, and Sara Duterte, the daughter of the fascist Rodrigo Duterte. More than ever, we need to use all means, whether offline or online, to combat dis- and misinformation and historical revisionism, and to resist the return of Marcos-Duterte to political power.

Sa ngayon, mayroon akong tinatapos na tribute print para kina Professor Leonilo “Neil Doloricon” at Parts Bagani na namatay lamang ngayong taon. Namatay si Prof Neil dulot ng sakit, habang pinatay naman ng gubyerno si Parts Bagani. Ang kanilang buhay at sining ay sentral na inspirasyon sa aking pagkatuto bilang printmaker.

Bukod dito, hinahanda ko muli ang katawan para sa mga ibebentang prints bilang fundraising sa sarili. Matapos ang phase na ito, babalik na ako muli sa pagbuo ng print na sana ay matapos ko bago ang 2022 National Elections. Ngayong election period, palala ng palala ang disinformation offensive sa social media upang ipanalo si Bongbong Marcos, anak ng diktador na si Ferdinand Marcos, at si Sara Duterte, anak ng pasistang Rodrigo Duterte. Ito ang panahon kung saan kailangan na kailangang gamitin ang kahit na anong pamamaraan, offline at online, upang labanan ang pagpapakalat na maling impormasyon at historical revisionism, at ang handlangan ang pagbabalik ng Marcos-Duterte sa pampulitikang kapangyarihan.

Who are some artists (living or dead) from the Philippines that have inspired you, that everyone should know about? And also, I know that you are an advocate for political printmaking worldwide- who are some artists from around the world that have inspired your work?

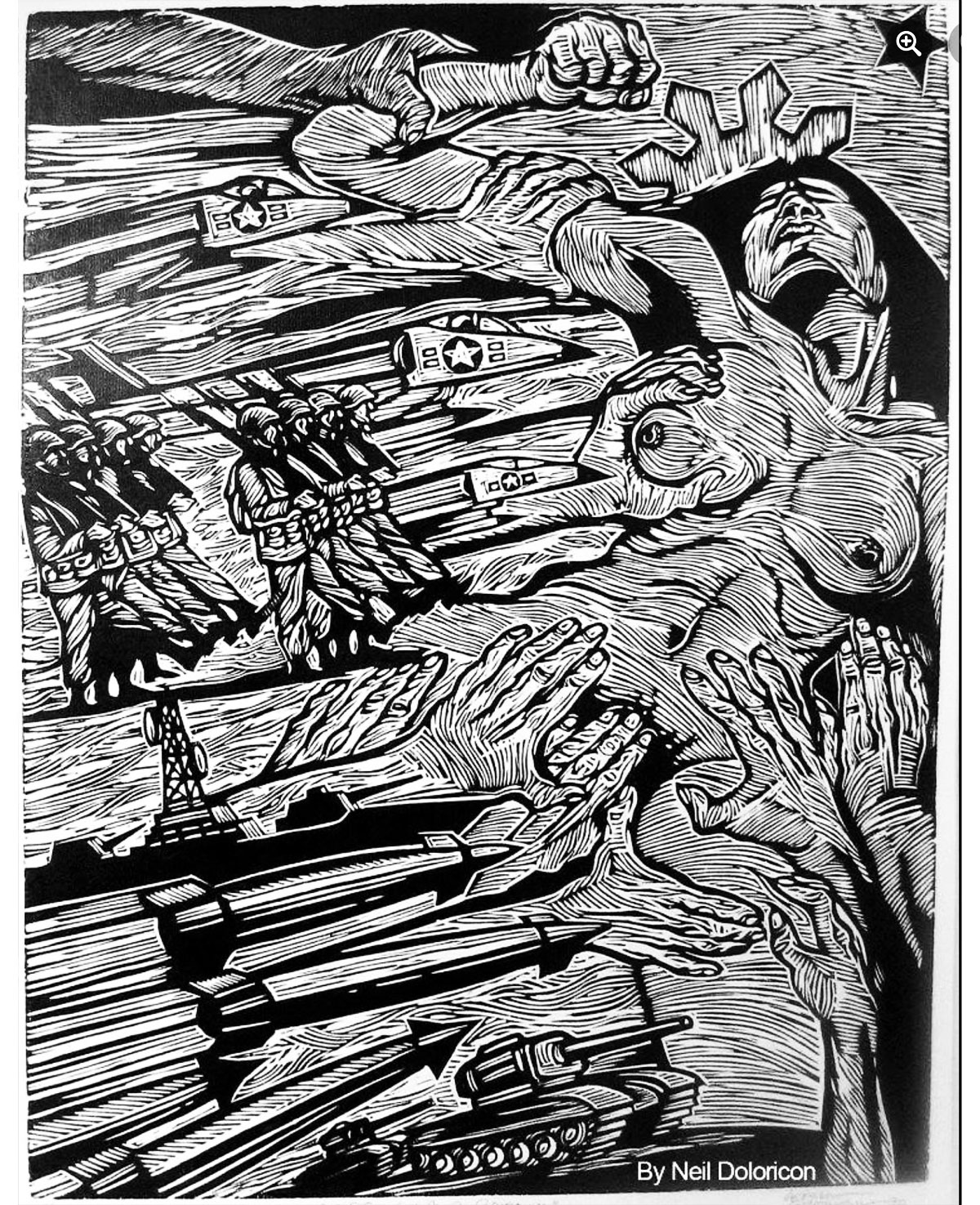

The life and works of Leonilo “Neil” Doloricon and Parts Bagani (mentioned above) are central to my printmaking practice.

Prof Neil was an educator and a visual artist who made sure that his art is reflective of our socio-political situations. He was a member of KAISAHAN, a social realist art collective that crafted protest art to expose social inequalities during Martial Law under the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos. After Martial Law, he continued to produce editorial cartoons, paintings and prints discussing the issues on agrarian reform, US imperialism, corruption, people’s democratic revolution, failed pandemic response, militarization on the countryside and many other issues and concerns of the Filipino people.

I fell in love with political printmaking after viewing his exhibit in Sining Makiling Gallery (University of the Philippines – Los Banos) back in the early 2010s. Among his powerful collection of political prints, Araw ng Kalayaan (Independence Day) is my personal favorite. An image of a naked female persona, a symbolism of the Philippine motherland, is being defiled by various hands that represent the continuous intervention of the United States in our local economy and military. His body of work boldy articulates his principle as an activist-artist to always use art as a tool and weapon to carve out fundamental changes in our society.

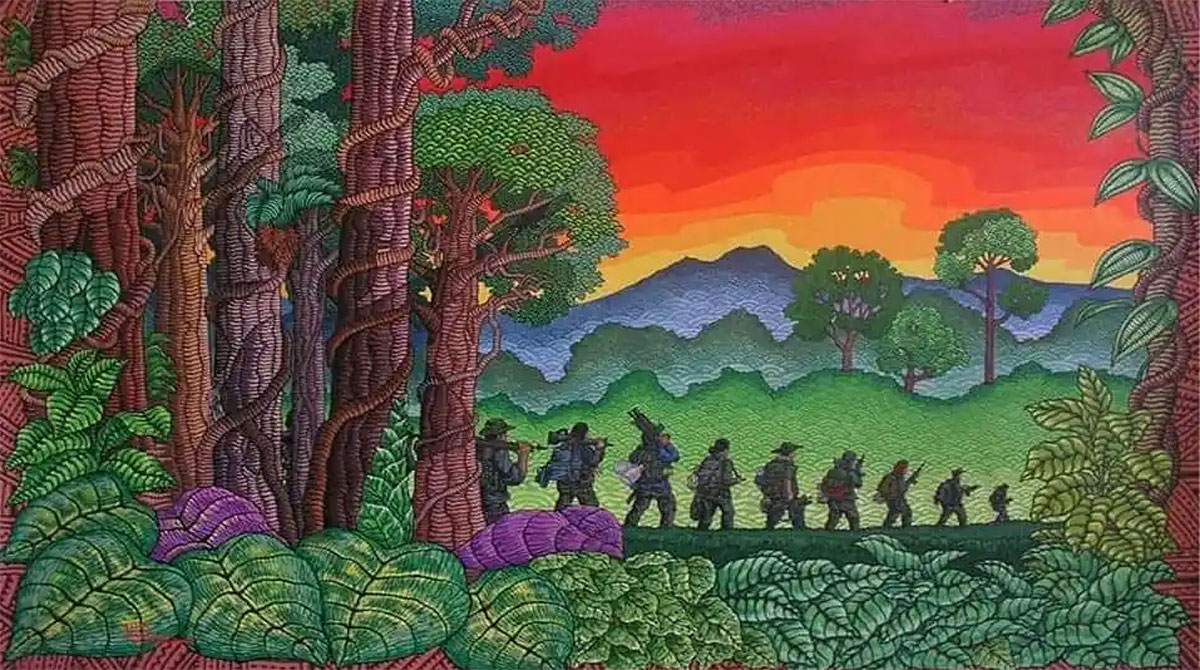

Parts Bagani, on the other hand, is also influential to my study of political graphics in the Philippines. He was a member of the New People’s Army (NPA), the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). Because of his revolutionary affiliation, he was murdered by the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) last August.

He was very prolific in making illustrations that depicted the daily lives of the people’s army, and that were used for educational discussions among their ranks and with the communities they visit (helping in the farm work of the peasants, launching military offensives against the AFP and so on).

Their life and works continue to influence me as an activist and as a fan of political printmaking due to how they skillfully demonstrated the unity of form and content.

I am also a fan of UgatLahi Artist Collective and Tambisan sa Sining because of the effigies and streamers they make for the people’s demonstrations. Their works are important components of our protest culture. I follow Renan Ortiz’s political cartoons, and Kartunista-Manunulat (KarMa) Kolektib’s zines. Recently, I discovered the works of Ylang Montenegro, Amiel Rivera, Dilag, Joyce Caubat and Saya Villacorta. We decided to form a printmaking collective, Printmaking for the People, to have a collaborative learning platform for printmakers to practice and create prints that will reflect Filipinos’ current conditions and aspirations.

Outside the Philippines, I am really hooked to Taller de Grafica Popular (Mexico) and Atelier Populaire (France). Similar to the reasons why I respect Prof Neil and Parts Bagani, the Taller and Atelier masterfully merged their sharp commentary of their socio-economic contexts with their distinct styles. The Atelier, who emerged during the 1968 protests in France, issued this collective statement in 1969:

“To the reader:

The posters produced by the Atelier Populaire are weapons in the service of the struggle and are an inseparable part of it.

Their rightful place is in the centres of conflict, that is to say in the streets and on the walls of the factories.

To use them for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect. This is why the Atelier Populaire has always refused to put them on sale.

Even to keep them as historical evidence of a certain stage in the struggle is a betrayal, for the struggle itself is of such primary importance that the position of an “outside” observer is a fiction which inevitably plays into the hands of the ruling class.

That is why this book should not be taken as the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action both on the cultural and the political plane.”

They explained that their silkscreen posters were tools for social change led by the toiling people.

This is also the principle of the Taller de Grafica Popular which was started by Leopoldo Mendez in 1937. Their manifesto states that their work is a reflection of the conditions and struggles of the Mexican peasants and workers. The members of Taller were able to do this because part of their artistic production was rooted in their close contact with the oppressed segments of their society:

“…We are with those who seek to overthrow an old and inhuman system within which you, worker of the soil, produce riches for the overseer and politician, while you starve. Within which you, worker in the city, move the wheels of industries, weave the cloth, and create with your hands the modern comforts enjoyed by the parasites and prostitutes, while your own body is numb and cold. Within which you, Indian soldier, heroically abandon your land and give your life in the eternal hope of liberating your race from the degradations and misery of centuries.

Not only the noble labor but even the smallest manifestations of the material and spiritual vitality of our race spring from our native midst. Its admirable, exceptional, and peculiar ability to create beauty — the art of the Mexican people — is the highest and greatest spiritual expression of the world-tradition which constitutes our most valued heritage. It is great because it surges from the people; it is collective, and our own aesthetic aim is to socialize artistic expression, to destroy bourgeois individualism.

We repudiate the so-called easel art and all such art which springs from ultra-intellectual circles, for it is essentially aristocratic.

We hail the monumental expression of art because such art is public property. We proclaim that this being the moment of social transformation from a decrepit to a new order, the makers of beauty must invest their greatest efforts in the aim of materializing an art valuable to the people, and our supreme objective in art, which is today an expression for individual pleasure, is to create beauty for all, beauty that enlightens and stirs to struggle.”

In An Artful Revolution: The Life and Art of the Taller de Grafica Popular, a documentary on the renowned printmaking collective released in 2008, Arturo Bustos Garcia shared that witnessing Diego Rivera and Jose Clemente Orozco create murals on public spaces where the masses could watch and interact with the famous artists made a strong impact on his practice, that art and the artist must be accessible to the people.

As an activist and as a student of printmaking in a country with a long history of oppression from foreign imperialist powers and local ruling class, the socio-political context in which the Taller de Grafica Popular and Atelier Populaire existed and how they used printmaking as tools for social change resonate with me. Currently, I also follow political printmakers on Instagram, such as Ricardo Levins Morales, printmakers featured on JustSeeds, and various printmakers from Latin America who use printmaking to amplify the call to oust their authoritarian governments.

Sentral sa aking printmaking practice ang buhay at sining nina Leonilo “Neil” Doloricon at Parts Bagani.

Si Prof Neil ay dating edukador at visual artist. Tiniyak niya na ang kaniyang mga likhang sining ay sumasalamin sa socio-political situations ng aming bansa. Siya ay dating kasapi ng KAISAHAN, isang social realist art collective na lumikha ng mga protest art upang ipakita ang pang-aabuso ng diktador na si Ferdinand Marcos noong idineklara nito ang Batas Militar. Matapos ang Batas Militar, nagpatuloy si Prof Neil sa paggawa ng mga editorial cartoons, paintings at mga prints na tumatalakay ng mga usapin hinggil sa repormang agraryo, imperyalismo US, korupsyon, ang pambansa-demokratikong pakikibaka, palpak na pandemic response, militarisasyon sa kanayunan at marami pang isyu ng sambayanang Pilipino.

Nakilala ko ang political printmaking noong makadalo ako sa kaniyang exhibit sa Sining Makiling Gallery sa UPLB noong 2010s. Mula sa koleksyon ng mga political prints ni Prof Neil, pinakapaborito ko ang Araw ng Kalayaan kung saan makikita ang imahe ng hubad na babae (na sumisimbolo sa Pilipinas) attila ginagahasa ito ng mga kamay na tumatayong simbolo ng patuloy na pakikialam ng Estados Unidos sa ekonomiya at hukbong sandatahan ng Pilipinas. Makikita sa kaniyang mga likha ang matalas na niyang prinsipyo bilang artista ng bayan: dapat laging gamitin ang sining bilang kasangkapan at sandata sa paghubog ng mahahalagang pagbabago sa lipunang Pilipino.

Influential din sa akin si Parts Bagani bilang sumusubaybay ng political graphics sa Pilipinas. Si Parts Bagani ay kasapi ng New People’s Army (NPA), ang armed wing ng Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). Bilang kasapi ng rebolusyonaryong organisasyon, siya ay brutal na pinatay ng mga pwersa ng Armed Forces of the Philippines noong Agosto.

Napaka-prolific niya sa paggawa ng mga illustrations na sumasalim sa pang-araw-araw na buhay (slice of life) ng NPA, gaya ng paglulunsad ng mga pag-aaral sa kanilang hanay at sa mga komunidad na kanilang napupuntahan, pagtulong sa farm work ng mga magsasakang kanilang ino-organisa, military work at iba pa.

Malaki ang influence nila sa akin bilang aktibista at bilang mag-aaral ng printmaking dahil sa talas ng content at husay ng form.

Fan din ako ng UgatLahi Artist Collective at Tambisan sa Sining dahil kaabang-abang ang mga effigies at streamers na ginagawa nila sa mga protest mobilizations. Nakaka-proud maging bahagi ng mass movement sa Pilipinas dahil mahalagang sangkap ng protest culture ang mga creatively sharp protest materials. Sinusubaybayan ko rin ang political cartoons ni Renan Ortiz at mga zines ng Kartunista-Manunulat (KarMa) Kolektib. Recently, nakaabang din ako sa mga prints nina Yllang Montenegro, Amiel Rivera, Dilag, Joyce Caubat at Saya Villacorta na kasama ko sa Printmaking for the People. Binuo namin ang printmaking collective para magkaroon ng collaborative learning platform for printmakers to practice and create prints that will reflect Filipinos’ current conditions and aspirations.

Kung lalabas naman ng bansa, paborito ko talaga ang Taller de Grafica Popular (Mexico) at Atelier Populaire (France). Gaya rin ng dahilan kung bakit ako nahuhumaling kina Prof Neil at Parts, napakahusay ng unity ng style at message ng dalawang collectives. Halimbawa, sumibol ang Atelier sa gitna ng 1968 protests sa France. Sa inilabas nilang collective statement noong 1969, malinaw ang kanilang ang kanilang orientation:

“To the reader:

The posters produced by the Atelier Populaire are weapons in the service of the struggle and are an inseparable part of it.

Their rightful place is in the centres of conflict, that is to say in the streets and on the walls of the factories.

To use them for decorative purposes, to display them in bourgeois places of culture or to consider them as objects of aesthetic interest is to impair both their function and their effect. This is why the Atelier Populaire has always refused to put them on sale.

Even to keep them as historical evidence of a certain stage in the struggle is a betrayal, for the struggle itself is of such primary importance that the position of an “outside” observer is a fiction which inevitably plays into the hands of the ruling class.

That is why this book should not be taken as the final outcome of an experience, but as an inducement for finding, through contact with the masses, new levels of action both on the cultural and the political plane.”

Matalas na pinaliwanag ng Atelier na ang mga nilikha nilang posters ay kagamitan sa panlipunang pagbabago na sinusulong ng mga nakikibakang mamamayan.

Ganito rin ang prinsipyo ng Taller de Grafica Popular na sinimulan nina Leopoldo Mendez noong 1937. Ipinaliwanag sa kanilang manifesto na ang kanilang mga likha ay repleksyon ng kalagayan at pakikibaka ng mga magsasaka at manggagawa. Nagawa ito ng mga kasapi ng Taller dahil bahagi ng kanilang artistic production ang mahigpit na ugnayan sa mga oppressed segments ng kanilang lipunan:

“…We are with those who seek to overthrow of an old and inhuman system within which you, worker of the soil, produce riches for the overseer and politician, while you starve. Within which you, worker in the city, move the wheels of industries, weave the cloth, and create with your hands the modern comforts enjoyed by the parasites and prostitutes, while your own body is numb and cold. Within which you, Indian soldier, heroically abandon your land and give your life in the eternal hope of liberating your race from the degradations and misery of centuries.

Not only the noble labor but even the smallest manifestations of the material and spiritual vitality of our race spring from our native midst. Its admirable, exceptional, and peculiar ability to create beauty — the art of the Mexican people — is the highest and greatest spiritual expression of the world-tradition which constitutes our most valued heritage. It is great because it surges from the people; it is collective, and our own aesthetic aim is to socialize artistic expression, to destroy bourgeois individualism.

We repudiate the so-called easel art and all such art which springs from ultra-intellectual circles, for it is essentially aristocratic.

We hail the monumental expression of art because such art is public property.

We proclaim that this being the moment of social transformation from a decrepit to a new order, the makers of beauty must invest their greatest efforts in the aim of materializing an art valuable to the people, and our supreme objective in art, which is today an expression for individual pleasure, is to create beauty for all, beauty that enlightens and stirs to struggle.”

Kwento nga ni Arturo Bustos Garcia sa dokumentaryong An Artful Revolution: The Life & Art of the Taller de Gráfica Popular (2008), napalaki ng impact sa kaniya ng art practice nina Diego Rivera at Jose Clemente Orozco dahil noong kabataan niya ay nakita niya ang dalawang tanyag na artists na lumilikha ng mga murals kahanay ang mga ordinaryong mamamayan.

Bilang isang aktibista at nag-aaral ng printmaking sa isang bansa na mahaba ang kasaysayan ng oppression mula sa foreign imperialist powers at local ruling class, nagre-resonate sa akin ang socio-political context kung saan umiral ang Taller de Grafica Popular at Atelier Populaire at kung paano nila kinasangkapan ang printmaking para sa social transformation. Sa kasalukuyan, sinusubaybayan ko rin ang mga political printmakers na nasa Instagram, gaya nina Ricardo Levins Morales, mga printmakers na featured sa JustSeeds, at iba’t ibang printmakers mula sa Latin America na ginagamit ang printmaking upang i-amplify na i-topple down ang kanilang mga authoritarian governments.

Anything else you want to add? Where can people find your work?

Others may find my prints and activist work on Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/minimumfare).

I am also a part of Printmaking for the People: https://www.instagram.com/printsparasabayan

and Art ATAK: https://www.instagram.com/artatakph/

Signal: A Journal of International Political Graphics & Culture is the collective project of Josh MacPhee and Alec Dunn. All copies of Signal are available for sale here on Justseeds.

Translations done by Jona (thank you!). Interview conducted via email in November, 2021.